11

11

Performing Creatively: Accessing the Stream Brainset

The quality of the imagination is to flow, and not to freeze.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON1

AT 3:25 PM ON JANUARY 15, 2009, U.S. Air Flight 1549 took off from New York's La Guardia airport bound for Charlotte, North Carolina, with Captain Chesley Sullenberger at the helm. Within six minutes the flight would be over and the crew of Flight 1549 would make aviation history. Shortly after takeoff the aircraft hit a flock of Canada geese, resulting in loss of thrust to both of the Airbus A320s’ engines. The aircraft began descending, with no chance of making it back to LaGuardia or even to a nearby private airport. With just enough altitude to make it over the George Washington Bridge, Sullenberger deftly set the large aircraft down in the Hudson River, saving the lives of all 155 people on board.2 On that day, the experience and skill of the pilot were a perfect match for a difficult challenge. On that day, Captain Sullenberger and his crew were able to stream their moment-to-moment responses to the unfolding events of the flight in a feat of improvisational skill; the landing of Flight 1549 was a heroic and creative performance.

Creative performances can occur in virtually every area of human endeavor. Any time you apply your accrued knowledge and skills to an ongoing challenge in a novel and original way, you are performing creatively and you are operating within the stream brainset.

The stream brainset is the brain activation state for what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow.”3 When you're in this state, you perform a novel dance of sorts in which your responses to each nuance in a challenging situation fully occupy your attention. In this brainset, you lose both your sense of self and your sense of time as you build a set of spontaneously and skillfully executed responses to the challenge. When you hear the cockpit voice recordings from Flight 1549, for example, you do not hear the panicked voice of a man who is focused on the possibility that he is one minute from death; what you hear is the voice of a well-trained professional who is fully engaged in his work.

The stream brainset4 allows you to piece together (or stream) a set of responses to a challenge, none of which may be creative in and of itself. However, the sum total of the responses results in an improvisational performance that researchers call “ecologically relevant creative behavior”; that is, the creative behavior has been shaped in part by your relationship to your current environment.5 This is the type of creativity demonstrated by jazz musicians, improvisational actors, neurosurgeons, novelists who are writing automatically, and tennis champions who are fully immersed in their work.

Whether you refer to it as “flow,” “peak performance,” being “in the zone,” or entering the stream brainset, the end result is a unique melding of self and action that feels almost religious in its intensity (or “surreal” in Sullenberger's words).6

Fortunately, you do not have to be involved in a near-death challenge like Flight 1549 to experience the state of flow generated by the stream brainset. According to Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced “Cheek-sent-me-high”), who has spent almost 30 years examining the psychological features of this state, any physical or mental activity can produce flow as long as it is a challenging task that demands full concentration and commitment, provides immediate feedback, and is perfectly matched to your level of skill. Let's look at the conditions of this state of flow as described by Csikszentmihalyi, in his book Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention:7

- There are clear goals. The endpoint and intermediate goals for the activity have to be established for flow to occur. Note that this is true whether your challenging activity consists of getting a plane safely on the ground or performing a piece of music. The pilot has a checklist of procedures to accomplish and the musician has a series of notes to play. In other words, there are “mile markers” along the route to the end-point of your activity.

- There is immediate feedback to your actions. You know whether or not you've reached each mile marker successfully. The musician can hear whether an appropriate note was played and the pilot gets feedback from the response of the aircraft.

- The level of challenge matches your skill level. If the level of challenge is too great, you'll feel anxiety and frustration. If the level of the challenge is too weak, you'll feel boredom. Only when your skill meets the right level of challenge can you enter the flow state.

When these conditions of flow are met, the ensuing mental state includes the following characteristics:

- There is a merging of action and awareness. This merge occurs when the challenge of the activity is such that it requires all of your attention and there are no attentional resources remaining with which to process other stimuli. According to Csikszentmihalyi, we can process about 110 bits of information per second. When your task requires that amount of attention, you won't have any left to devote to self-consciousness.

- Distractions go unnoticed. All attention is directed to the task at hand.

- There is no worry of failure. Attention is focused on the here and now, and there is no room for concern. For instance, Sullenberger was asked in a CBS interview if he had worried during the minutes after the bird strike that he couldn't land the plane successfully. He stated emphatically that no such thought had entered his mind. He was certain of his ability to do the task.

- Self-consciousness disappears. The boundaries of the ego seem to dissolve and you become part of something bigger than yourself, in harmony with the universe. As an example, Sullenberger noted in the interview with CBS that he initially felt a wave of intense reaction to the plight of the aircraft. He had to put that aside before he could focus on landing the aircraft. Once that reaction was sidelined, his focus was entirely consumed by the work at hand and his self-conscious reactions receded.

- Time becomes distorted. Time may speed up so that hours seem like minutes. Or time may slow down. For example, you seem to have all the time in the world to get into position to return the serve from your tennis opponent.

- The activity becomes an end in itself. That is, the activity becomes intrinsically rewarding rather than being a means to an end. Sullenberger was working toward a goal of getting the aircraft on the ground—not toward getting his fifteen minutes of fame on the evening news.

Clearly, the experience of flow is possible across a large swath of human behavior that can be considered creative due to its novelty and adaptability. In this chapter, we'll examine flow and the stream brainset to discover how you can use this state to increase your moments of creative production and performance.8

Defining the Stream Brainset

I've defined the stream brainset as a brain state in which time disappears, you lose your sense of self, and your focus is totally on the task at hand. You become one with your work. This level of absorption is reminiscent of the absorb brainset. However, with the stream brainset you are engrossed in self-initiated activity directed outward toward the environment, whereas with the absorb brainset you are engrossed in information coming in to consciousness either through your five senses or through the activation of memories or visual images. The vectors of information and activity are going in opposite directions in these two brainsets.

What factors can account for this state in which you flawlessly fit your performance to the challenge facing you? First, you need the appropriate level of expertise to succeed at your task; second you need to be intrinsically motivated to persevere in the activity; and, finally, you need to act with what I call “trained impulsivity” (that is, without consciously evaluating your moves) in a series of semistructured steps as you respond skillfully to the challenging activity. In other words, you need to improvise. Let's look at each factor individually.

Appropriate Expertise

You need the right kind of expertise to enter the stream brainset. Clearly the expertise has to be appropriate for the type of challenging work in which you're engaged (expertise in playing the violin won't help you meet the challenge of landing an airplane). However, the expertise has to be more than appropriate to the task; the components of that expertise have to be represented in the implicit memory networks of the brain.

Implicit memory contains information that you've learned to the point that it has become automatic. This is sometimes referred to as “overlearning” or “muscle memory.” You generally cannot describe the contents of implicit memory in words, but you can access it without consciously thinking about it (examples include how to ride a bike or play a musical instrument). In contrast, explicit memory includes information that you can access consciously. Most of what you learned at school (such as the names of the oceans or the elements in the periodic table), is represented in explicit memory, as are your personal autobiographical memories.9 To illustrate the difference, think, for instance, of a six-year-old child who is speaking in his native tongue. He has no explicit knowledge of the rules of his language, yet he is able to use appropriate grammar and syntax without effort. When he speaks, he is accessing implicit memory to form sentences. Now compare that to the adult who is learning a second language. She will learn the rules of conjugation, grammar, and sentence structure for the new language, and she will access these explicitly as she forms sentences with the new language. Her speech will be more effortful and lack the smooth delivery of implicitly accessed speech.

Retrieval of memory from the implicit and explicit systems uses different parts of the brain. This is important. When you're engaged in a challenging activity, you don't have time to send messages from the executive center through the hippocampus to call up the information you need piece by piece (and in the right order) from explicit memory storage. Rather, you need the expert knowledge to stream automatically from implicit storage to the brain's premotor cortex (which will prepare the knowledge to be converted into action).10

As an example, when a jazz musician first learns to play an instrument, information about how to produce each note is held in explicit memory. However, as she grows more proficient, she no longer has to think about which keys to press to produce the B-flat scale. Similarly, a pilot like Sullenberger learns to fly an airplane explicitly; however, after years of practice and drills, knowledge of flying skills is gradually transferred into the implicit memory system. The experienced pilot automatically reacts to forces on the aircraft to maintain a desired flight path without having to consciously compute the probable effect of such forces on the trajectory of the flight.

Developing implicit expertise requires time, practice, and dedication. Scientific research is remarkably consistent in finding that expertise in most fields takes about 10 years to develop. The first evidence for this “10-year rule” was presented by William Chase and Nobel Prize-winner Herbert Simon in their famous study of chess players. They discovered that it takes 10 years of hard practice before a novice chess player can become an expert. This even applied to Bobby Fischer who became a grand master at the age of 16. His youthful acquisition of expertise was the result of an early and intense interest in chess since the age of six (exactly 10 years before he ascended to grand master status).11

Since Chase and Simon's study, investigators have looked into other areas of exceptional performance; they have found the 10-year rule applies virtually across the board—from science to musical composition to creative writing to dance. Geoff Colvin, in his bestseller Talent Is Overrated, suggested that even the Beatles didn't begin producing music that transformed the domain of rock ‘n’ roll until Lennon and McCartney had been practicing together for 10 years. In fact, researcher K. Anders Ericsson of the University of Colorado at Boulder and his colleagues found so much evidence for the 10-year rule that Ericsson claims the difference between the elite performer and the novice is not so much innate ability as it is the hours of serious practice put into the domain.12 Finally, Howard Gardner notes how surprised he was to find evidence for the 10-year rule in individuals as diverse as Albert Einstein, T. S. Eliot, Pablo Picasso, and the other creative luminaries whom he studied for his book Creating Minds.13

Although there have, of course, been some exceptions to the 10-year rule (it seems to take somewhat less time to develop expertise in writing poetry than in performing heart surgery), the point is that it takes many years of practice to internalize skills in a particular domain of work to the point that they are represented in the implicit knowledge base. Once you have assimilated the complex level of knowledge that constitutes expertise, you are in a position to begin to develop your own style and produce innovations that will rock your field.

While it may be discouraging to consider the length of time necessary to become an elite expert in any given domain, remember that everyday creative acts (the kind that can enrich your life and contribute to your family's and community's well-being) can be accomplished with implicit skills that don't achieve world-class status. A novice can surely enter the stream brainset while participating in a creative activity. Even if you have not mastered the more complex aspects of a domain, you still likely have mastery over elementary aspects of an activity.

For instance, when I took watercolor lessons for the first time several years ago, I was able to spend one highly enjoyable afternoon painting a planter of geraniums that sits on my front porch. I became so involved that I totally lost myself in the activity. Time and distractions did indeed dissolve, and before I knew it, the sky was getting dark—six hours later! I ended up framing that painting—not because it was a masterpiece of art, but because I had had such a phenomenal time painting it. So how could I—a novice watercolor artist—get into the stream brainset? After all, it's not like I didn't have any relevant implicit skills: I had had years of experience holding drawing utensils in the form of pens, pencils, and crayons. I could draw lines and circles, and I also had years of experience applying colors to surfaces (I have painted every room in my house at least twice and I put on makeup almost every day). Bottom line: if you have some skills partially represented in implicit memory and you have a challenging task that employs those skills, you too can access the stream brainset.

Besides having information stored in implicit memory for instantaneous retrieval, there is a second reason that you need to develop some expertise in the domain in which you face challenging activity. If you have internalized the expertise, you have also internalized the understanding of what makes a good performance in that area. In other words, you automatically know if you're doing it right. Why is this important? It allows for continuous feedback as you perform the activity. In some instances, the continuous feedback will come from the environment. For instance, if you're playing tennis, the feedback will come from the effectiveness of your volleys and the accumulation of points. If you're playing in a jazz ensemble, the feedback will come from the way your work blends with that of other musicians.

However, if you're writing Chapter Sixteen of your novel, continuous feedback will only come from your own appreciation for the “rightness” of your sentences and paragraphs as they stream from your pen or keyboard. And that comes from knowing what makes good writing (see Chapter Ten). Indeed, for many areas of science, invention, and the arts, the only feedback the creator receives during the challenging activity is his or her own internalized knowledge that the work is going well.

Csikszentmihalyi is adamant that this continuous feedback is necessary for the experience of flow; it provides the motivation to continue despite the challenging nature of the activity. When you see that work is progressing well, you are intrinsically motivated to continue it.14

Intrinsic Motivation

Besides requiring that you possess implicit skill, the stream brainset demands that you be engaged in an activity that is intrinsically motivating to you. Intrinsic motivation means that you are involved in the activity because of some internal reward you get from the work rather than from some extrinsic reward (such as fame, fortune, or staying out of jail). When you are in the stream brainset or flow, the activity in which you're engaged becomes, according to Csikszentmihalyi, “auto-telic.” That is, performing the activity becomes an end in itself.15

Psychologist Teresa Amabile, a professor at the Harvard Business School and consultant to high-tech companies such as E Ink (the group that developed the innovation behind electronic reading devices like Kindle), has done extensive work on the role of intrinsic motivation in creative work. Her research has repeatedly demonstrated that when individuals are intrinsically motivated they perform more creatively than persons with the same skill level who are working merely for extrinsic rewards such as prizes or money. For example, in a series of studies during the 1980s, Amabile demonstrated that grade school-age children who were allowed to work on a creative project such as a collage produced more creative results (as judged by artistically trained raters) than children who were offered prizes for their work. Amabile has also studied motivation in artists, writers, and creative workers in consumer product and high-tech companies. This research also indicates a correlation between intrinsic motivation and creative involvement. In an interview with Bill Breen of Fast Company, she reported that creative thinkers “don't think about pay on a day-to-day basis. And the handful of people who were spending a lot of time wondering about their bonuses were doing very little creative thinking.”16

How can you increase your intrinsic motivation in the activities that fill your daily life? There are two basic ways: first, you can spend more time doing activities that you truly enjoy, and second, you can increase the motivational salience of the activities you are already doing. (To work with both of these options, see Stream Exercises #2 and #3.)

One aspect of intrinsic motivation is finding activities in which you achieve an optimal level of arousal. If the level of challenge in an activity is too great, you will feel anxiety and frustration (too much arousal). If the level of the challenge is too weak, you will feel boredom (too little arousal).17 To the extent that you have control over the challenge, try to arrange a match between the challenging aspects of the task and your own personal level of expertise. If the task seems too simple, find a way to kick the challenge up a notch so that it will occupy your complete attention. There are several ways to do this:

- Set time limits on the task or establish deadlines. Example: you've been tasked with putting together 50 copies of your report on the environmental impact of bird control on airport property (ask the pilots of Flight 1549 about this one!) to present at a conference. Time yourself to see if you can get one copy collated and into its bright yellow folder every minute. Can you beat a 50-minute self-imposed deadline? The time will go much more quickly if you set a timed goal for yourself and treat it as a challenge rather than as a dull chore.

- Increase your appreciation for the task. Example: if your task is to dust the house, take time to appreciate each piece of furniture as you dust it. Think back to how you acquired each piece and allow yourself to indulge in memories of that time in your life. Also, as you move each item to dust under it, think about how fortunate you are to have that item. The gratitude you feel for all that you own will increase your intrinsic motivation in the task and you will begin to lose yourself in the work.

- Increase your standards for task performance. Example: if your task is to write 120 thank-you cards for your wedding gifts, rather than just reeling off the same formulaic sentiments on each card, try to make each card different with a special twist or well-worded original message. As you take more pride in your work, your intrinsic motivation will rise and you'll begin to lose yourself in the task.

On the other hand, if you're concerned that the task seems too challenging for your skill level, find a way to bring the challenge down a notch so you won't feel anxious or overwhelmed by it.

- Break the task down into smaller manageable parts. Example: if your task is to have your 70,000-word nonfiction manuscript completed in six months, break it down into chapters, and break each chapter down into segments. Although it's still important to keep in mind how the individual parts relate to the whole, working on one part at a time is a much less daunting and more intrinsically motivating task than facing an entire overly challenging project.

- Reinforce your skills. It may be wise to postpone a significant challenge if you feel that you really don't have the implicit resources to handle it. However, it's more likely that you just need to remind yourself of your own existing resources. One way to do this is to read your Successful Challenges list (see Stream Exercise #4).

Improvisation

So far we have talked about ways to enter the stream brainset through matching your skill to a challenging and intrinsically motivated task. When you are streaming, you lose yourself in the activity and your moment-to-moment responses seem automatic and appropriate. What we haven't discussed is the mental vehicle you use to make this happen. That vehicle is improvisation.

Improvisation is a series of sequential responses to either internally or externally generated stimuli that is performed extemporaneously. What's interesting to note is that the individual responses that make up the improvised performance are not necessarily creative; it is the accumulation of a series of responses, each being limited to one of several choices, that comprises the creative product. Consider, for example, the improvisation of the jazz musician. Each step of the improvisation is limited not only by the 12 possible notes on the chromatic scale and the finite number of beats to a measure, but also by the note that was previously played (jazz progressions follow certain rules even though there is choice in which progression to select). Each note or each progression of notes is not creative…but the way the progressions are assembled is creative!

Although it is more commonly associated with the performing arts, improvisation can occur in virtually any domain of endeavor. Improvisation is the prototypical creative behavior. It involves freely generated choices, which are adapted to ongoing conditions and directed toward the accomplishment of a specific goal. Once initiated, improvised responses seem to stream from the implicit memory system as a series of “actions performed without delay, reflection, voluntary direction or obvious control in response to a stimulus.” This is actually the definition of “impulsivity,”18 and, in fact, improvisation includes responding with “trained impulsivity.”

Unlike the impulsive behavior evident in disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the impulsive behavior associated with improvisation and the stream brainset is nonrandom. It is based on a limited set of possible responses represented in expert training “programs” residing in your implicit memory. To put it more succinctly, when a challenging activity is encountered for which you have developed expertise, you will respond impulsively and automatically with one of your implicitly stored expert training programs. These programs are activated in rapid succession in response to the fluid challenge of the situation.

Now of course, “impulsive” is a dirty word to some of you even when paired with the word “trained” (especially if the evaluate or reason brainset is your mental comfort zone). If that's the case, you're in good company. Fear of impulsively uttering the wrong sequence of words, for example, is one of the main reasons that public speaking is the number one social phobia among adults.19 If you find that you have trouble letting go of planned and consciously controlled behavior, then one of your missions has to be to loosen up and learn to trust the expertise within you.

In order to move more easily into the stream brainset and the state of flow, you need to feel comfortable with improvisation. You can start by thinking about how you respond when playing a video game. Take the popular game Tetris, for instance.20 Each move has only a small number of possible responses; yet it's your ability to string the responses together in rapid order that indicates mastery of the game. It's impossible to play at a high level without disengaging your need to consciously plan and make decisions. The game moves too fast. Yet once you develop the skill to make moves without thinking about them, your skill level matches the challenge of the game and a state of flow results. (This is no accident, by the way; video game designers purposely build the conditions of flow into their game programs.) So is the secret to the stream brainset to play more video games?

Well, no! But you may be able to get a feel for streaming responses through small doses of video game exposure. You can get practice at improvisation by joining a local improv theater group, taking improv lessons, or studying jazz or other forms of improvisational performance. (To practice improvisation, see Stream Exercise #5.)

We have now seen that the combination of implicitly stored expertise, a challenging activity that provides intrinsic motivation and the optimal level of arousal, and the willingness to let go of tight cognitive control (thus allowing yourself to improvise) can lead to the experience of flow. Because you control intrinsic motivation and optimal arousal level, you can increase your experience of flow by purposely entering the stream brainset.

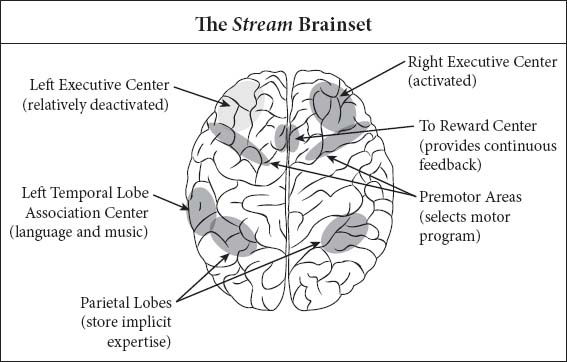

Neuroscience of the Stream Brainset

While we can't (yet!) scan the brains of tennis champions that are “in the zone” as they volley with their opponents, or of pilots as they are guiding a crippled aircraft to safety, researchers have been able to look at the brains of another group of creative performers as they engage in the improvisational behavior associated with the stream brainset. The interesting findings from studies of highly trained pianists during musical improvisation show a brainset that is defined by the following:

- Deactivation in the left executive center (the big honcho of consciously directed behavior)

- Activation of the premotor areas (involved in selecting motor action programs)

- Activation of the temporal lobe association center (which helps process music but may also be helpful in other forms of improvisation)

- Mild but continuous activation of the reward center21

In a 2007 study of classically trained musicians, Swedish investigators Sara Bengtsson and Frederic Ullen of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm teamed up with Csikszentmihalyi to study classically trained concert pianists as they played a specially made piano keyboard in an fMRI scanner. In another study, conducted in 2008 by Charles Limb and Allen Braun of the National Institutes of Health, researchers looked specifically at highly trained jazz pianists. In both studies, the brain activation patterns of musicians during improvisation were compared to the patterns generated by music played from memory. This allowed researchers to subtract the parts of the brain that are lit up during music production and to isolate brain areas activated solely in response to improvisation.22

The results of both studies indicate that the left executive center is not involved in improvisation. In fact, the one study that looked at deactivation patterns showed a decrease in activity in the left DLPFC, a condition that neuroscientist Arne Dietrich23 refers to as “transient hypofrontality” (we discussed the transient hypofrontality hypothesis way back in Chapter Five in conjunction with the absorb brainset). Hypo (low) + frontality = (prefrontal cortex) = low activation of the prefrontal cortex. This state results in cognitive disinhibition (also discussed in Chapter Five and elsewhere), which allows information assembled in other parts of the brain to stream forward without being censored by the executive and the judgment centers.

Why would you want to deactivate the executive center—that most modern and sophisticated of all brain regions—during a time when sophisticated and complex behavior is most desired? The answer is that the executive center is limited in the number of elements it can process at one time. (This is due to the limited capacity of working memory, which has been shown to hold only around four chunks of information at once.)24 Implicit memory systems, however, are not limited in capacity and can process many elements in parallel. If we assume that each of these elements represents an action program that is well represented in implicit memory, we can see why it's important to allow them to feed forward in rapid succession in response to a challenging situation that requires multiple ongoing responses—without the meddling of the capacity-limited executive center.

Another area of the brain that is active during flow is the reward center of the brain. Ongoing positive feedback (from either the environment or your own expert knowledge of how the work is going) causes mild but continual activation of the reward center. The firing of the reward center may be so mild that it doesn't even register in conscious awareness. But it's sufficient to affect behavior and motivate you to continue in your ongoing efforts.25 As Csikszentmihalyi points out, people who are in the midst of a flow experience are not aware of intense pleasure. However, once the flow activity is completed, they look back on it as an exceptionally positive experience that they will do almost anything to repeat.26 In this way, the stream brainset provides motivation for you to gain more expert knowledge and seek ever more challenging activities. Thus progress—on the personal and the societal level—advances.

When to Access the Stream Brainset

Whenever you must perform a challenging task, either on the job or in your personal life, remember what you've learned about accessing the stream brainset. Use the strategies outlined in this chapter to bring the challenge in line with your skills, and try to increase your intrinsic motivation in the task. The more you can become absorbed in the task, the more enjoyable it will become and the higher your performance level will be.

You can also use this brainset in the elaboration phase of the creative process to flesh out your ideas. Once you have your creative idea (from the absorb, envision, connect, or reason brainset), and you've evaluated it, try to lose yourself in the process of bringing it to life. By using all your implicit resources and by becoming one with the work, you can, say, develop the characters of a novel, create a moving musical arrangement for your new melody, add a cool fort and a picnic table to that backyard swing set project, or make your “better mousetrap” more attractive and user-friendly. Whatever your idea, make your effort in the elaboration phase of development a flow experience.

Finally, access the stream brainset in the implementation phase of your creative project. If you can be completely engaged with your creative idea when you present it to others, the enthusiasm will be contagious. You will be able to get your work out there in a way that inspires excitement and appreciation.

In this chapter, you've seen how implicitly learned expertise, intrinsic motivation, and the ability to improvise can lead to creative performance in the stream brainset. Entering this brainset takes practice. However, as you acquire expertise and practice improvisation, you will find your level of intrinsic motivation for challenging activities is rising. You will find that engaging in creative actions will become its own reward as you slip ever more easily into the flow of the stream brainset.

You have now seen how each of the CREATES brainsets affects and enhances your ability to be creative, innovative, and productive. But the brainsets don't operate in isolation. In Part III—“Putting the CREATES Brainsets to Work”—you'll learn strategies for switching brainsets at appropriate times and applying them to your real-world work and leisure. You're about to put it all together to make Your Creative Brain work for you!

Exercises: The Stream Brainset

The following sequence of exercises, developed as part of a creativity workshop, work best to promote the stream brainset when completed in order. Very much like streaming itself (in which each response you make to a challenge is a function of the previous choice), each exercise in this chapter builds on the previous one and prepares you for the next exercise.

Stream Exercise #1: Implicit Expertise

Aim of exercise: To discover areas in which you have expertise that can be utilized in flow experiences representative of the stream brainset. You will need a piece of paper and a writing utensil. This exercise will take you 10 minutes.

Procedure: Make two columns on your paper. Label one column “Areas of Acquired Expertise” and label the second column “Areas of Developing Expertise.” In the first column, list all the areas in which you have acquired implicit expertise. Note that these areas must have a “performance” or execution element to them rather than being areas of general explicit knowledge. Examples of implicit expertise would include activities that most of us can already perform using implicit memory, such as walking, reading, speaking in our native language, driving a car, riding a bicycle, eating with utensils, and drawing basic symbols. Add any specialized expertise you may possess by virtue of your profession, such as skill at flying, dry cleaning garments, performing heart surgery, or welding metal.

Next, list expertise you may possess by virtue of your hobbies or interests, such as playing an instrument, skateboarding, skiing, speaking fluently in a second language, telling jokes, or belly dancing.

In the second column, list all the areas of expertise that you are currently acquiring. These would be areas in which you are a novice but are working toward greater implicit expertise. These could include any area in which you are currently taking lessons or in which you're interested but have not yet committed the skill to implicit memory.

When you've completed your lists, look over the Acquired Expertise list. Note just how multifaceted your current skills actually are. Next, look over your list of Developing Expertise. Add one activity to this list in which you would like to develop skill.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one stream token for completing the exercise and one stream token for actually taking the first step toward developing your newly chosen skill.

Stream Exercise #2: Intrinsic Motivation: Identifying Intrinsically Motivating Activities

Aim of exercise: To explicitly determine what activities are intrinsically motivating for you. You will need a piece of paper and a writing utensil. This exercise will take you between 10 and 15 minutes.

Procedure: At the top of your paper, write the heading “Intrinsically Motivating Activities.” Now it's time to figure out what you love to do. Think about the following questions: what do you look forward to doing each day? Your list should consist of activities in which you are an active rather than a passive participant. (Passive participant activities include sitting in front of the television and zoning out, getting drunk, binge eating, and sleeping. Active participant activities include just about anything that involves moving your muscles or exercising your mind.) Make sure to include activities that you look forward to at work, as well as during leisure hours and on the weekends. Check the list of activities you wrote down in the Implicit Expertise exercise for additional ideas of what motivates you.

On the other side of the paper, start a second list headed “Potentially Motivating Activities.” On this list include any activities that you think you would be interested in trying. Be sure to list several activities that involve creative work. These could include writing, drawing, playing music, cooking, sculpting, pottery, quilting, woodworking, dancing, and so on—any type of creative work that you think you would find interesting. It doesn't matter if you think you wouldn't be good at them. Don't let fear of failure limit your list!

When you're finished writing all the activities you can think of that are intrinsically appealing to you, put your list aside for a few days. If you run across activities that look interesting, add them to your list. Try to think about your list as you go through each day this week and add activities as appropriate.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one stream token for completing this exercise.

Stream Exercise #3: Intrinsic Motivation: Doing What You Love27

Aim of exercise: To increase intrinsic motivation in your daily activities. One of the most validated findings in research on highly creative people is that they are intrinsically motivated in what they do. They also arrange their lives so that they can do more of the work that they find intrinsically rewarding. You will need a highlight marker and two copies of the Daily Activities Calendar from Appendix Three. (You can also print out the calendar from the Web site http://ShelleyCarson.com.) This is a two-part exercise. Part One will take you 10 minutes a day for seven days. Part Two will take 20 minutes during the day following completion of Part One.

Procedure: Part One: Fill out the Daily Activities Calendar each day for one week. Each two-hour block of time should reflect the major (most time-consuming) activity you engaged in during that time. Try to fill in the calendar at approximately the same time each day—either just before you go to bed or upon rising in the morning.

When you've completed the seven-day Calendar, take a few minutes to go through your weekly activities and highlight those you enjoyed. In other words, mark activities that were intrinsically motivating. You now have an idea of how much of your time you spend doing activities that you love. If less than half of your time was highlighted during the last week, continue with Part Two of this exercise.

Part Two: Your goal in this part of this exercise is to increase the number of hours you spend involved in activities that you love during the upcoming week. You must replace one of the two-hour segments that were not highlighted last week with an intrinsically rewarding activity for the upcoming week. Take the blank copy of the Daily Activities Calendar and schedule in an intrinsically motivating activity right now. You can choose any activity that you identified in Stream Exercise #2.

You can repeat the exercise by continuing to fill in the Daily Activities Calendar each day for the next week, making sure to increase the amount of time you spend doing things you love. (The goal is to work toward spending more and more time in activities that are meaningful and rewarding.)

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself two stream tokens for completing the Calendar for one week. Give yourself one token for scheduling in an additional intrinsically motivating activity. Finally, give yourself two tokens for actually engaging in that intrinsically motivating activity during the upcoming week.

Stream Exercise #4: Intrinsic Motivation: Successful Challenges

Aim of exercise: To increase your intrinsic motivation in challenging activities by reinforcing your confidence in your implicit resources. You will need a paper and writing utensil, or you can complete this exercise on your computer's word processor. It will take you approximately 30 minutes.

Procedure: You're going to make a list that you'll want to refer to in the future. Make a heading at the top of your paper titled: “Successful Challenges.”

- Make a list of five different situations in which you were able to use your internal resources to deal with a serious challenge. Make each challenge a subheading on your paper. For each situation:

- Describe the challenging situation.

- Describe your response and the implicit skills you used (these could be physical, mental, or interpersonal skills).

- Describe the positive outcome of this challenge in detail.

Whenever you worry that a current situation is too challenging for you, get out your list and remind yourself of your great store of personal resources.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one stream token for completing this exercise.

Stream Exercise #5: Practicing Improvisation: TV Narrator

Aim of exercise: To improve your ability to improvise by responding to a series of changing stimuli. You will need a stopwatch or timer and a television. This exercise will take you between five and 10 minutes.

Procedure: Turn your television on to a drama or comedy show. This can be a movie, a sitcom, or a soap opera. However, it has to be a movie or episode that you've never seen before. Wait until a commercial break is over so that you'll have a period of 10 minutes of commercial-free time. When the show resumes after the commercial, set the timer for five minutes and turn down the TV volume so that you can no longer hear the sound.

Now narrate the show out loud. Describe all the action, the emotions of the characters, and how the plot is progressing as it happens. Don't stop talking until the timer sounds.

Try to do this exercise once a week and work up to 10-minute narrations to improve your ability to respond spontaneously to the action on the television. This will help you develop improvisation skills.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one stream token each time you complete the exercise.