10

10

Using Emotion Creatively: Accessing the Transform Brainset

Feeling and longing are the motive forces behind all human endeavor and human creations.

—ALBERT EINSTEIN1

THE TRANSFORM BRAINSET is a state of consciousness in which your attention is occupied by thoughts relating to yourself and your feelings (generally negative feelings).2 In past chapters we've looked at ways you can enter brainsets that will allow you to generate creative ideas (the absorb, envision, connect, and reason brainsets), evaluate your ideas (the evaluate brainset), and develop and implement your ideas (the reason brainset). The one thing we haven't talked much about is your feelings. Your emotions color the way you see your environment, the way you recall memories, and, indeed, all aspects of your cognition. Your emotions can either get in the way of your creative efforts … or you can use them to enhance your creativity. In this chapter, we'll discuss both the good and the bad aspects of self-consciousness and emotions, as well as how you can transform emotional experience into creative products.

Let's look at some different levels of emotion and why they have an impact on your efforts to be creative.

Levels of Emotional Experience

Much of the time we're not consciously aware of our feelings; they run in the background occupying only a minimal amount of our attention. This low-level background feeling state is referred to as stream of affect by psychologists David Watson and Lee Anna Clark (“affect” being the psychological term for emotions).3 We may notice this stream of affect as a mild positive or negative state (as in “I'm having a good day” or “I got up on the wrong side of the bed”), if we notice it at all. Yet, regardless of how little of our attention it is claiming, our stream of affect influences how we see the world. Positive stream of affect makes us somewhat more open to novelty, while negative stream of affect closes us up somewhat to new ideas (every teenager knows it's best to approach Dad about a loan when he's whistling than when he's scowling).

The next step up in emotional intensity is a mood. When you're experiencing a mood state, you may feel anxious, irritable, contented, self-conscious, or “blue.” Mood states can be of relatively long duration, some lasting for months, and they occupy more of your conscious attention. Certain moods, such as anxiety or melancholia (a.k.a. depression), can make it difficult to concentrate. If negative moods persist for extremely long periods, they can interfere with both your work and your interpersonal relationships. In such cases, you may need to seek the help of a mental health professional (please note that modern evidence-based treatments are very effect in alleviating these debilitating and dysfunctional negative mood states).4

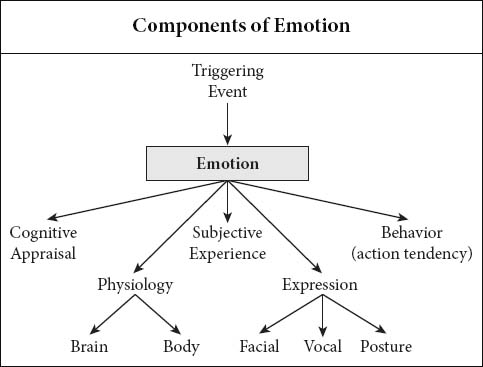

The most intense emotional state you can experience is the onset of an actual emotion. Note that while we refer to all feeling states as emotional states in everyday speech, actual emotions have specific characteristics (see the diagram below). Emotions are events of relatively short duration, usually lasting less than an hour. They are a response to a particular trigger (either in the environment or an internal event such as a traumatic memory or the experience of pain), and they are extremely intense. They are accompanied by characteristic facial expressions, thoughts, physiological changes, and subjective feelings. They also prime the body to behave in specific ways called “action tendencies” (for example, the action tendency associated with fear is the “fight or flight” response, while the action tendency for anger is aggression).5 Emotions demand your attention; you will be focused on the emotional material to the exclusion of other thoughts. If the emotion is intense enough, you may feel completely controlled by it.

This is called “emotional hijacking.” Emotional hijacking may take the form of a fit of violent rage (extreme anger), a suicide attempt (extreme despair), or a panic attack (extreme fear). When you're emotionally hijacked, your action tendency becomes an action imperative, and you have little conscious control over your actions.6 This is, in part, the basis of the “temporary insanity” plea.

One of the functions of emotions is to alert you to the need for action (hence the action tendency response). Emotions, moods, and stream of affect absorb more of your attention if they have a negative valence than a positive one. That's because positive feelings suggest that all is right with your world and that you're interacting with your environment in a manner that is conducive to your survival. Full speed ahead and no action needs to be taken. However, negative moods and emotions grab your attention because they're an indicator that something may be wrong and that you may need to act. Negative moods can affect your creative efforts to the extent that they pull your attention away from the creative process. The more negative emotion you're feeling the harder it will be to focus on generating novel and original ideas.

In the chapters that precede this, one clear theme is that creativity is associated with desiring novelty, activating the reward center, and upswings in positive emotion. There is no mention of fear, anxiety, or depression. In fact, when you're in a fearful or depressed state (as noted in Chapter Nine) you avoid novelty. Fear and depression are a turnoff for the idea-generating brainsets that we've discussed. So if you're self-absorbed in some negative feeling state (in other words, you're in the transform brainset), does that mean you can't be creative?

NO! (that's an emphatic no). In fact, many highly creative individuals—both past and present—are clearly (as we used to say) neurotic.7 They have experienced long bouts of anxiety, irritability, or depression; yet they have found ways to use their state of negative affect to enhance their creativity. They've done this in two ways:

- First, by using creative work as a way to assuage their negative feelings; in this way, the negative feelings act as a motivator to be creative and creative work acts as a type of self-administered therapy.

- Second, by using the negative feelings as subject matter for their creative work. As we shall see, many a painting, poem, novel, and musical composition has focused on its creator's state of negative emotions.

I don't recommend purposely getting yourself into a negative feeling state (unless you're using method acting to prepare for a theatrical part). But if you're already in the transform state, why not make the most of it and use it to your advantage? Later in this chapter, we'll examine ways you can use that negative emotion to propel yourself to a better state through creative endeavors, and we'll also look at how others have used negative moods to inform their creative work.

Defining the Transform Brainset

The transform brainset is basically a brain state in which your feelings are mildly negative and your thoughts are self-referential.8 As a rule, you are not consciously directing these thoughts; they are rather of a mind-wandering, stream-of-consciousness nature. As with the envision brainset, you engage in “what if?” thinking; but rather than the purposeful imagining that characterizes the envision brainset, what-if-ing in the transform brainset is not purposefully directed and often includes themes of worry, anxiety, resentment, self-pity, or regret. At other times, themes of thinking in the transform brainset may tend toward fantasies of self-aggrandizement, idealized romance, power, or revenge. While this doesn't sound very healthy, neuroscience research indicates that all of us slip into these types of self-referential fantasies at times. Our idle thoughts (times when we're not consciously directing our thoughts) may reflect current mood states, frustrations, and longings. The transform brainset is identified by three factors: self-centered thought, negative feeling states, and dissatisfaction. Let's look at each of these factors separately and determine how you can make creative use of them.

Self-Conscious Thought

Self-conscious thought is thought that's directed toward yourself and your relationship to your environment. This can and (and generally does) include comparing yourself or your circumstances to those of other people. This can lead to resentment for those who seem to have it better than you do and to self-pity and feelings that the world is unfair. This can also lead to feelings of personal worthlessness and concern about your future. Finally, it can include excessive guilt and regret about things you have done or have failed to do in the past. When thoughts such as these begin to stream into awareness, many people have trouble turning them off. In fact, they may become caught in a downward spiral of negative self-assessment.9

While these particular thoughts are psychologically unhealthy and usually don't reflect your true value and worth, there is a silver lining to this state; it produces a state of internal reflection. Your internal world is where all creative ideas are generated and also where all psychic healing takes place. While you're there, how about doing a little exploring and investigating? Your investigations can yield enormous knowledge about yourself and the human condition in general. (For practice in self-investigation, see Transform Exercises #1 and #2. However, please note that self-investigation should take place in a state of mild dysphoria or negative mood. If you're feeling hopeless or out of control, you should not perform the transform exercises and you should seek the help of a mental health professional.) Note that when you've had enough self-reflection and you want to move on to thinking about other things, you can use the Self-Monitoring Exercise from Chapter Nine or the Thought-Stopping Exercise from Chapter Eight to help you get out of the self-conscious state. (By the way, you don't need to be in a state of dysphoria to engage in self-reflection; however, self-reflection often results from such a state.)

While trying to understand your complexities as a person, it is also important to recognize that you have enormous strengths as well as flaws. To focus on the negative aspects of your character is to disregard half your essence. It isn't realistic. You are a person with great potential to be creative. Use your self-knowledge of both your problems and your strengths to guide your creative expression. (To investigate your personal strengths, see Transform Exercise #3.)

Negative Feeling States

Negative feeling states are part of the normal ebb and flow of human emotions, of course. They provide a natural counterpoint to the joyful and happy occasions of life, and they add to the rich tapestry of human experience. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, we seem to have developed a fear of negative mood states; when we encounter them, we immediately do everything we can to extricate ourselves from these states—with drugs, liquor, sex, or thrills—without taking time to understand what these moods are trying to tell us.10 If you are in the transform brainset, you may want to give some real thought to why you are there rather than taking the first available train out of that town.

Explorations of negative feelings have been the subject matter for creative works since at least the time of the early Greeks, when Aristotle first associated poets and playwrights with melancholia. Here is a very small sample of work from creators who have used their negative mood states as subject matter to connect with others and to share their mutual experience of important aspects of the human condition:

- Emily Dickinson's famous poem “There's a Certain Slant of Light” describes depression on a winter's afternoon (perhaps an early description of seasonal affective disorder [SAD]).

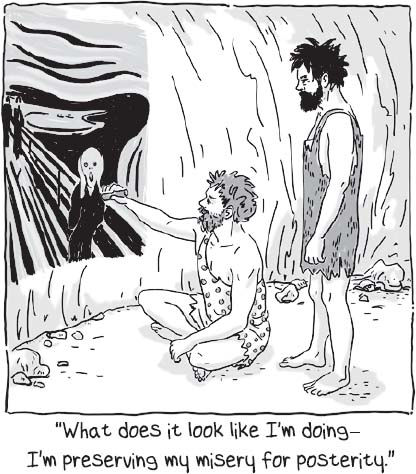

- Edvard Munch's famous Expressionist painting The Scream portrays a state of high anxiety.

- The entire genre of blues music is based on a negative feeling state. It gets its name from the term blue devils, which the African American community has used for centuries to denote a state of melancholy and sadness.

- Playwright Eugene O'Neill's masterpiece Long Day's Journey into Night portrays an entire family's dysfunction and melancholy. O'Neill won a Pulitzer Prize posthumously for this work.

- In 2005, a celebrated art exhibit called Melancholy: Genius and Madness in the West, opened in Paris at the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais. The exhibit was devoted to art inspired by depression and melancholy and featured work spanning 2,000 years. (Negative feelings have been around a long time!)

- Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 6 in B minor, “Pathétique,” is often referred to as the composer's suicide note (he died nine days after conducting its premier performance). Author and musicologist Joseph Horowitz says “this is a work which cannot be listened to casually … here's a guy who's in an extreme personal crisis baring his soul.”11 (Again, if your negative mood is this severe, do not write music; get the help of a mental health professional.) For more information on the connection between creativity and mental illness, see Mental Disorders, Transformation, and Creativity.

- J. D. Salinger's classic 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye is the consummate description of teenage angst.

You, too, can use your negative moods as inspiration to encode emotions in artistic form that others may be feeling but do not know how to express. You can do this through music, writing (both poetry and prose), art (both drawing and sculpture), and drama. Florists know how to express mood through flower arrangements, and chefs can use spices and herbs to connote different moods. You can use virtually any domain to creatively express your negative mood in a way that may resonate with the emotions of others. You don't have to have training or innate talent to do this. Personal expression of emotion is powerful, even from the untrained creator. (For practice in describing your feelings creatively, see Transform Exercises #4 and #5.)

Dissatisfaction

The negative feeling state of the transform brainset goes hand-in-hand with a basic state of personal dissatisfaction. These two factors of the brainset feed off of each other as dissatisfaction with oneself can breed negative mood, while negative mood breeds dissatisfaction. However, the up side of this for your creative endeavors is that dissatisfaction can also breed creativity. In fact, contentment is often the enemy of creative effort.12 (Note that although creativity is associated with a positive upswing in mood, the positive mood that evokes divergent thinking is not in the form of contentment but rather of pleasant surprise, mild euphoria, pride, positive expectation, or joy.)

Creativity is predicated on some sort of dissatisfaction with the current state of things; otherwise, the impetus for creativity would be absent. The creative person is always on the lookout for life circumstances that could be improved. However, in order to improve circumstances, you need to be very clear about what it is that's causing dissatisfaction. Once you can identify the problem then you can use divergent thinking or the problem-solving steps we discussed in Chapter Eight to find and implement solutions. (For practice writing about negative experiences in a way that can improve both your physical and mental health, see Transform Exercise #7.)

Whether through music, art, writing, drama, a new video game, or some other medium, one of the best uses you can make of your dissatisfaction is as an inspiration to endure suffering and to prevail over it. Suffering is part of the human condition. Yet perhaps one reason we are encountering an increase in the rate of depression worldwide13 is that our ability to endure suffering has diminished with the availability of quick fixes that promise the rapid end to all negative feeling states. If we don't learn that we can endure negative feelings—and come out on the other side of them stronger—then we will be subject to episodes of depression whenever the normal vicissitudes of life deal us a blow. One use of your negative feelings is as a starting point for the artistic expression of the process of humans using their strengths to overcome hardship in the modern world. (See Transform Exercise #8.)

Creativity as a Coping Mechanism

One of the most potent methods of dealing with negative moods and dissatisfaction is to express them in the form of creative work. As we saw from the list under “Negative Feeling States” previously in this chapter, many creative people before you have used their negative mood state as subject matter for artistic achievements. Likewise, many creative people have used their creative endeavors to soften the bitter sting of the negative mood state. For instance, the English novelist Graham Greene wrote: “Art is a form of therapy. Sometimes I wonder how all those who do not write, compose or paint can escape the madness, the melancholia, the panic inherent in the human situation”14

In psychoanalytic terms, the energy of negative emotions that is too dangerous or unacceptable to be expressed directly can be redirected into creative work that is more socially acceptable. This is a type of beneficial defense mechanism called sublimation. As an individual releases negative energy into the creative work, the power of the negative emotions is weakened.

Indeed, the experience of delving into a creative endeavor is such an effective way of coping with negative moods that dozens of creative therapies have sprung up to help individuals who suffer from depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and even psychosis to cope with their demons. Therapies include art, drama, writing, music, and dance therapies. The growing body of scientific literature that reports on the effectiveness of these therapies as adjunct treatments for mental illness attests to the healing power of creative activity.15

The benefits of creative therapies include a group setting (misery loves company) as well as a trained therapist to encourage you and help you interpret your work. However, you don't need a therapy group or a trained professional to receive the therapeutic benefit of creative work. A pen, a guitar, a computer keyboard, or a set of colored pencils will be adequate. Nor do you need to limit your endeavors to the “arts.” Eminent scientists such as Isaac Newton were able to lose themselves in their creative work for days on end.16 The experience of losing yourself in your work will be discussed more fully in the next chapter on the stream brainset. For now, the take-home message is that your negative mood, your self-referential funk, and your dissatisfaction can be a potent motivation to get creative!

Mental Disorders, Transformation, and Creativity

Because we've been discussing negative moods and creative therapies in this chapter, now might be a good time to address the association between mental illness and creativity that has received so much attention in recent years … and, in fact, throughout recorded history. Since the days of the ancient Greeks, people have associated creative genius with eccentricity and even madness. Plato described the creativity associated with poetry as “divine madness,” and Aristotle added that “no great genius was without a mixture of insanity”17 In 1889, Cesare Lombroso, the Italian physician and pioneer criminologist, published a book called The Man of Genius, in which he described the odd and sometimes bizarre behavior of numerous creative luminaries of the past. He pointed out, for example, Samuel Johnson's need to touch every lamppost that he passed, and composer Robert Schumann's belief that his musical compositions were dictated to him by Beethoven and Mendelssohn “from their tombs.” Lombroso believed that geniuses and violent criminals shared a common genetic inheritance. He concluded that “Unfortunately, goodness and honor are rather the exception than the rule among exceptional men, not to speak of geniuses”18

In more recent times, creativity has been associated with manic depression, alcoholism, and psychosis proneness. Psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison believes, for example, that many creative luminaries from the past, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Emily Dickinson, T. S. Eliot, Victor Hugo, Edgar Allan Poe, Tchaikovsky, Handel, Rachmaninoff, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Vincent van Gogh, Gauguin, and Georgia O'Keefe, suffered from manic depression or other mood disorders. Author Tom Dardis points out that of the eight American novelists who have won the Nobel Prize for literature, five have been alcoholics. And many creative luminaries have displayed psychotic-like behavior.19 William Blake claimed that both his poetry and his paintings were presented to him in visions by visiting spirits who sometimes jostled him while competing for his attention. Tesla, the scientist credited with developing alternating electrical current, is reported to have suffered from columbiphilia (pigeon-love) and triphilia (obsession with the number three), as well as from auditory and visual hallucinations. Charles Dickens is reported to have fended off the imaginary urchins of his novels with an umbrella as he walked the streets of London. And Beethoven had such disregard for his personal cleanliness that friends had to undress him and wash his clothes while he slept.20

Clearly, we can find many examples of highly creative people from the past who do indeed appear to have had mental disorders. Likewise, we can cite current research that indicates that the risk of having a psychiatric disorder such as manic depression is elevated among highly creative individuals. One such study, in which Kay Jamison examined award-winning British artists and poets, indicated that the artist/poet group was six times more likely to have been treated for manic depression than members of the general public.21 But even if we use the results of this study (which are on the extreme end of such research findings), we see that only 9% of the artists and poets had manic depression, and that over 90% had no such affliction. Although the eccentricities of high-profile creative individuals, such as a Howard Hughes, a Pablo Picasso, or a Michael Jackson, may receive attention from the press and publishing worlds, they do not characterize the majority of persons who make substantial creative contributions.

Why then would the rates of certain types of mental disorders be higher in at least a subset of individuals recognized for their creativity? The answer to that question is complex. However, there is some evidence to suggest that certain mental disorders may facilitate entry into some altered states of consciousness that resemble the brainsets associated with spontaneous thinking in the CREATES model.22

For example, mild alcohol or drug intoxication turns down the volume on the part of the brain that evaluates the appropriateness of ideas and behavior. This state of “disinhibition” allows more ideas to flow into your conscious awareness than would otherwise be filtered out by your brain before the ideas even reach the threshold of consciousness.23

Likewise, the bipolar individual who is cycling into a manic state (or more accurately, the premanic state called hypomania) is highly motivated to perform goal-directed activity. This activity may be in the form of prototypical creative acts, such as painting, writing, composing, inventing, or entrepreneuring. (Of course, it may also have deleterious results, such as shopping sprees that include the purchase of Lear jets and Caribbean islands, ill-considered sexual liaisons, and messianic crusades.)24

Psychosis-prone individuals may be privy to unusual mental associations that allow them to make connections between distal bits of information (remember that the ability to combine disparate concepts is the hallmark of creative thought). This may be due in part to a feature of the psychotic brain called hyperconnectivity, in which parts of the brain that are not normally connected for functional reasons light up at the same time. Though this tendency to make unusual associations can sometimes lead to novel and original ideas, it can also lead to bizarre notions, such as the belief that Martians are trying to steal your thoughts, or that Katie Couric is sending you secret love messages through the television screen.25

By studying creative individuals with mental disorders, we've been able to understand more about the brain states that are involved in creative thought and productivity. In fact, we owe a huge debt of gratitude to those creative pioneers who have struggled against their inner demons to bring beauty and comfort to all of our lives. These individuals have courageously taken their mental discomfort and transformed it into creative work that benefits us all. We owe them gratitude not only for their acts of creativity but for what they've taught us about the creative process in spite of their suffering. Thanks to them, we are learning more about how to access the mental brainsets that can bring forth a fountain of creative ideas. Now, with new knowledge of the brain, we can learn to control these brainsets and use them to increase innovation and productivity.

The take-home message that I want to emphasize about creativity and mental disorders is that in small doses, mood disorders or psychosis-proneness may be beneficial to creativity primarily because they facilitate entry into brain states (such as absorb, envision, connect, or transform) that allow more information that is ordinarily censored by brain filters to be available to consciousness for creative combination.26 However, most highly creative individuals do not suffer from mental illness; they are able to access the appropriate brain states through mental discipline, just as you can use the exercises in this book to facilitate those same brain states.

Neuroscience of the Transform Brainset

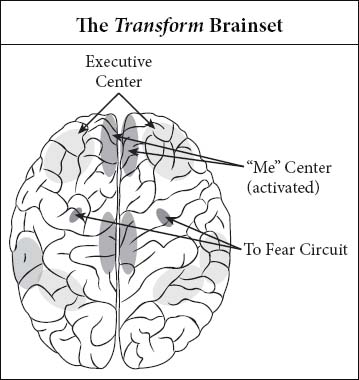

In 2001, neuroscientist Marcus Raichle of Washington University in St. Louis identified a brain network that is active when the human brain isn't involved in purposeful problem solving. Raichle dubbed this brain circuit the “default mode” because the default activation pattern of the idle brain seems to include this network.27 As we noted in Chapter Four, the default mode activates when you are daydreaming, thinking about the past, or are absorbed in self-related thought. It deactivates when you actively try to solve problems.

The default mode is important in the transform brainset. It includes the “me” circuit described in Chapter Three, as well as parts of the temporal lobes that are involved in memory retrieval. When you're involved in the transform brainset, your “me” center is activated, along with emotional circuits in the limbic center deep in the brain. In particular, the amygdala and its connections to the prefrontal lobes (the fear circuit) are active as you process negative moods.28

The transform brainset also connotes withdrawal from the environment. This is directed by activation of the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS), first described by the late British psychologist Jeffrey Gray, as a response to fear and other negative emotions. The counterpart to the BIS is the Behavioral Activation System (BAS), of which the reward center is part.29 This system activates when you are purposefully engaged with your environment. (These two systems are the human versions of the approach and avoidance systems that are found in even very primitive organisms.) An effective way to overcome the self-referential, stream-of-consciousness anxiety state that is associated with the transform brainset is to purposely turn up the volume on your BAS. In other words, if you want to overcome fearful or negative emotional states, become more—rather than less— engaged with your world.30 This takes courage, but the creative person is ultimately courageous (you have to be if you are planning to introduce new ideas into the world!).

When to Access the Transform Brainset

The transform brainset can imbue your creative projects with great emotional power. You can enter this brainset temporarily if you need to harness emotion for character development, musical or artistic effect, or performance realism. However, you may find yourself feeling negative and questioning your abilities if you access this brainset. Be certain that you have developed the flexibility to change brainsets before you enter this one purposefully (see Chapter Twelve).

The exercises and reflections in this chapter have ideally provided you with some ideas about how to use negative and self-referential brain states to transform your negative thoughts and feelings into creative material. You can use your negative moods to create expressive materials in the form of art, writing, music, or drama that allow you to share your experience of negative states with others who may not have the talent to give expression to their deepest emotions. You can also use your experience of negative moods to depict the inherent strength of humanity by creating work that shows the journey from despair into hope. Finally, you can use creative work as a method of dispelling negative feeling states through immersion in the creative process.

Whereas the transform brainset is a state of negative mood and hyper-self-awareness, the brainset we'll look at in the next chapter takes you to the opposite extreme. There, you will learn to lose your sense of self in challenging and creative performance. You are about to enter the stream brainset, perhaps the most rewarding and delightful brain activation state that your creative brain can achieve.

Exercises: The Transform Brainset

Transform Exercise #1: Thinking About Yourself: The Wallet

Aim of exercise: To focus your thoughts on yourself and to better understand yourself. You will need a blank sheet of paper, a writing utensil, and your wallet, purse, backpack, or briefcase. This exercise will take you around 15 minutes.

Procedure: Empty the contents of your wallet, bag, or briefcase onto a table. Examine the contents.

- Pick three items that you think are representative of your qualities, personality, or character. (Note that if something strikes you as missing from your wallet, purse, or bag that you think most other people would carry, you can also choose that missing item as one of your three choices.)

- Now write a short paragraph about each of these three items and how each relates to your personality. Don't worry about spelling, punctuation, or grammar. Just write what you feel.

- When you're finished, look over what you wrote. Did you learn anything about yourself? Did your paragraphs reflect a positive or a negative view of yourself? Will this exercise change what you carry around with you?

- You can do this exercise with other places where you keep your belongings as well, such as a bureau drawer, closet, medicine cabinet, or the glove compartment of your car.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one transform token each time you complete this exercise.

Transform Exercise #2: Thinking About Yourself: Fictional Character

Aim of exercise: To focus your thoughts on yourself and to better understand yourself. You will need a blank sheet of paper and a writing utensil. This exercise will take you around 15 minutes.

Procedure: Think of a fictional character that reminds you of yourself as you currently are. This could be a character from a novel, a comic book, a movie, or a television show.

- Now write a paragraph about all the things you have in common with this character. Take into consideration your physical appearance, your personality characteristics, your family and professional circumstances, your love life, your aspirations for the future, and any other points of comparison that you can think of.

- Next write a paragraph about the ways you differ from your chosen character, using the same points of comparison listed above, plus any other differences you can think of.

- Finally, write down whether you would like to know this person in real life. Why or why not? When you're finished writing, look over your work. Did you learn anything about yourself?

- As a follow-up to this exercise, pick a fictional character who reminds you of the person you would like to be. Use all the same points of comparison in this second exercise that you just used in the first. When you are finished with both the similarities and differences paragraphs, look over your work. Are you more similar to your ideal fictional character than you originally believed? Can you use the comparisons in the differences paragraph as a basis for personal change in the future?

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one transform token for completing this exercise.

Transform Exercise #3: Thinking About Yourself: Core Strengths31

Aim of exercise: To focus your thoughts on yourself and understand your strengths. You will need a blank sheet of paper, a three-by-five index card, and a writing utensil. This exercise will take you between 10 and 15 minutes.

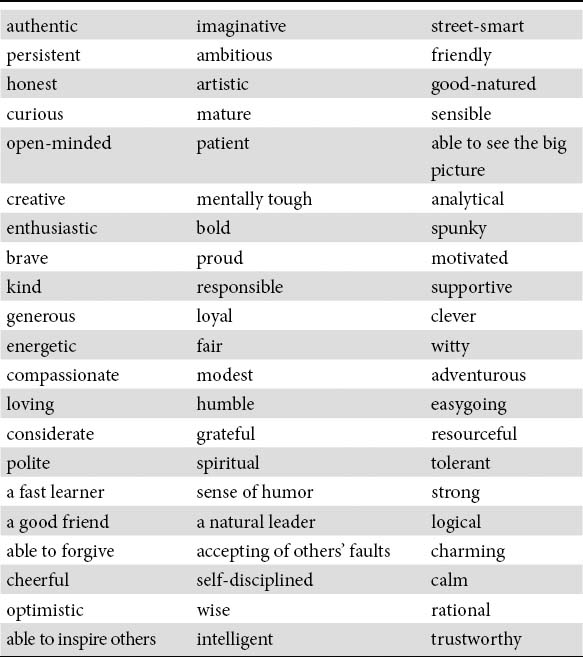

Procedure: Look at the following list of personal strengths.

On the piece of paper, copy down all the strengths that describe you. Make sure that you include the trait “creative,” even if you are new at exercising your creative powers. If you're unsure of whether other strengths apply to you, think of whether anyone has ever told you that you had this strength. If you're still unsure, ask someone who knows you well whether they would attribute this strength to you.

- If you think of a strength trait that you possess that's not on the list, add it to your paper.

- Your list should include at least 10 strength traits. If you have fewer than this, go back through the list of strengths and think about those that you rejected. You will be able to find additional strengths if you think about it.

- Now look over your list and rank these strength traits according to how important they are to you in dealing with the problems you may encounter in life, with the number one trait being the most important. Make sure to choose the trait “creative” among the top five.

- These top five traits are your core strengths. Write them on the three-by-five card as five sentences, each beginning with the words “I am [strength trait].” At the bottom of the card write the words “I vow to use these strengths to prevail over adversity and achieve my goals.” Sign the card and date it.

- Put this card in a place where you can read it first thing in the morning and last thing at night. You might keep it in your purse or pocket, on the bathroom mirror, or inside the door of a kitchen cabinet. Use it as a reminder that you have many core strengths at your disposal that you can count on when things get tough. Your creative brain is one of those strengths.

If you're using the token economy system, award yourself three transform tokens for completing this exercise, including the core strengths index card.

Transform Exercise #4: Feelings: Describing Your Feelings

Aim of exercise: To better understand and describe your feelings. You will need a blank sheet of paper and a writing utensil. This exercise will take you around 12 minutes.

Procedure: Sit in a quiet place and try to step outside your current feeling state and observe it objectively.

- Write down a description of your feeling state. What emotions, moods, or affect are you experiencing right now? Try to write at least three sentences that describe how you feel.

- Now write what physical feelings you're experiencing right now. Scan your body for any area that might feel tense, painful, or constricted. Write down these physical feelings. Do you think they are related to your feelings? If so, write down how you think your current physical and emotional states are connected.

- Now think about your mental state. Are you having trouble concentrating due to your feelings?

- Finally think about your action tendencies. Are you feeling the urge to act in a certain way? Run away or escape, lash out at someone or something, disappear into the floor, put your arms around someone?

- The goal of this exercise is to write as detailed and precise a description of your feeling state as possible. When you've finished, read over what you wrote. Does it adequately describe what you're feeling?

- Try to do this exercise at least once a week. It will provide insight into your feelings and also develop your skills of self-expression. This exercise will also help you develop emotional intelligence, a quality that will enhance your creative work.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one transform token each time you complete this exercise.

Transform Exercise #5: Feelings: Depicting Your Feelings

Aim of exercise: To help you better understand and describe your feelings. You will need a blank sheet of paper or a sketchpad and a set of crayons, colored markers, or watercolor crayons. You will also need a timer or stopwatch. This exercise will take you around 10 minutes.

Procedure: Sit in a quiet place and try to step outside your current feeling state and observe it objectively.

- Now set the timer for five minutes and depict your feelings on the paper. (Note: If you are using colored markers, put a piece of cardboard behind your paper so the color doesn't bleed through.) Use whatever colors seem appropriate. Don't censor yourself; just get out the colors and go to town. Draw whatever comes into your mind. Your work can be abstract, representational, or anything in between, as long as it comes from your inner well. Try to draw for the entire five minutes.

- When the timer sounds, look over your work. If you have more to add, set the timer for another five minutes.

- When your picture is complete, look over your work. Does it adequately depict what you're feeling? Did you learn anything about yourself from examining the picture?

- Try to do this exercise at least once a week. It will provide insight into your feelings and also develop your skills of self-expression.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one transform token each time you complete this exercise.

Transform Exercise #6: Feelings: Music and Moods

Aim of exercise: To help you better understand your feelings and to practice “mood flexibility.” You will need access to your music library (CDs, MP3s, or tapes). This exercise will take you around 30 minutes plus the time it takes you to select music for the exercise.

Procedure: Think about the music you listen to and pick out three pieces of music from your library that are consistent with the mood or feelings you're experiencing now. The pieces could be any type of music from classical to jazz to rap. They could be instrumental or vocal. You can mix styles—the three pieces do not have to be from the same genre.

- Now pick out three pieces of music that are consistent with the way you'd like to be feeling. It may take you a while to locate these three pieces as it is more difficult to think of positive things when you're in a negative mood (this is called mood-congruent memory).

- Finally, select one piece of music that you don't mind listening to but that doesn't really evoke any mood or emotion in you.

- Set up a playlist with the three pieces that match your current mood followed by the neutral piece and concluding with the three pieces that match your desired mood.

- Now listen to all seven pieces with your eyes closed. During the mood-congruent (first three) pieces, really get into the mood they represent. During the mood-incongruent pieces (last three), try to match your mood to the music and really get into that mood.

- When the play list is complete, check your current mood. Were you able to alter it to be more consistent with your desired mood?

- Music is a powerful mood regulator. You can experiment with your playlist to find the music that works best for you. The point is to start with music that matches your current mood and move toward music that matches your desired state. If you just play happy music when you're in a low mood, it can backfire and lead to a deeper negative mood. The trick, again, is to match your current mood and gradually effect a change. After practice, you may be able to alter your mood with a single piece in each of the mood-congruent, mood-neutral, and desired mood categories.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself a transform token each time you complete this exercise.

Transform Exercise #7: Dissatisfaction: Writing About Your Discontent

Aim of exercise: To practice self-expression concerning an area of dissatisfaction in your life and to promote cognitive processing of this dissatisfaction state. Note that this exercise should be done on three consecutive days at roughly the same time each day. Do not start the exercise unless you can commit 15 minutes to it every day for three days. You will need a lined notebook and a writing utensil, or you can use the word processor on your computer. This exercise is called “emotive writing.” It was developed by psychologist James Pennebaker of the University of Texas. The exercise has been tested on thousands of individuals and has been shown to have beneficial effects on both physical and mental health.32

Procedure: Find a quiet spot where you can write uninterrupted. Set the timer for 15 minutes and begin to write using the following guidelines:

For the next three days, write about your very deepest thoughts and feelings about an extremely important issue that has affected you and your life. In your writing, really let go and explore your very deepest emotions and thoughts. You might tie your topic to your relationships with others, including parents, lovers, friends, or relatives; to your past, your present, or your future; or who you have been, who you would like to be, or who you are now. You may write about the same general issues or experiences on all days of writing or on different topics each day. No one will see your writing but you. Don't worry about spelling, sentence structure, or grammar. The only rule is that once you begin writing, continue to do so until your time is up (adapted from Pennebaker, 1997, p. 162).

When your writing is finished for the day, put it away and don't look at it again. Start your writing tomorrow without reviewing what you wrote today. The value of this exercise is in the actual writing. You never need to look at what you wrote to get the benefit of it.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself six transform tokens for completing all three days of writing.

Transform Exercise #8: Dissatisfaction: Redemptive Story

Aim of exercise: To practice self-expression concerning an area of dissatisfaction in your life and to promote the alleviation of your dissatisfied state. You will need a lined notebook and a writing utensil, or you can use the word processor on your computer. You will also need a timer or stopwatch. Note that this exercise may take you more than one session to complete. However, once you start it, you must complete it. Plan to work on this exercise for 20 minutes at each session.

Procedure: Find a quiet spot where you can write uninterrupted. Set the timer for 20 minutes. Your goal is to write a short story, complete with character change and a plot, using the following guidelines:

Your story should have a main character who has the same dissatisfactions in life that you have. You must describe this character and his or her dissatisfactions in detail. The plot of the story is a description of how your main character changes his or her own life so that the sources of dissatisfaction are alleviated. The events of this story should be realistic (no being saved by Captain Kirk and the starship Enterprise or a knight in shining armor!). The character must earn his or her way out of the unbearable present to a better future. Along the way there should be some character development—that is, your main character should experience personal change in some meaningful way. You may write the story in either first- or third-person voice.

Force yourself to finish this story. Do not leave your character dangling out there in a dissatisfied state!

When you have finished the story, read it over. Did you learn anything from your character's growth that could be useful in your own life?

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself four transform tokens for completing the story.