3

3

Tour Your Creative Brain

YOUR BRAIN IS A novelty-seeking machine. It contains mechanisms that promote exploring the environment, learning new information, and synthesizing that new material into original ideas. There is no doubt about it: your brain is built for creativity.

Of course, that's not all your brain is built for. Besides being a factory of creative ideas, your brain is charged with other tasks, such as keeping you alive. Your brain must monitor both the external environment (the world) and the internal environment (your body) for signs of threat and then respond appropriately when threat is detected. That involves interpreting the intentions of other people, recalling scenarios from your past to see if something that's happening out there right now might follow a pattern that didn't work out so well for you before, and figuring out what excuse you're going to give your spouse this time for not getting the trash out soon enough for the weekly pickup. (However, note that this last aspect of insuring your survival—like so many others—also requires creativity.)

So when it's not preoccupied with your survival, your brain can devote more of its resources to being creative. The way the brain is connected to itself is crucial to creativity. We've known for decades that some of the most creative ideas come from making associations between remote or seemingly disconnected ideas or concepts.1 Newer research is indicating that connections between disparate areas of the brain are also associated with measures of creative thinking.2 Indeed, creativity is all about making associations. But how does your brain make associations? To understand this, we first have to understand how parts of the brain communicate with each other.

How the Brain Communicates with Itself

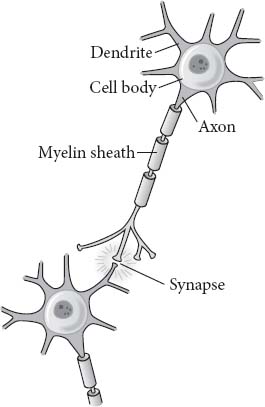

Your brain contains around 100 billion nerve cells, called neurons, each of which can form up to 10,000 connections with other neurons, making a total of over 100 trillion connections.3 That's the storage capacity of your brain—and it is tremendous. To fully understand how to enhance your creativity, let's take a closer look at neurons and the other building blocks of the brain.

Each neuron is composed of a cell body, a set of arms called dendrites that receive information from other neurons, and an axon that transmits information to other neurons (see below). Axons are protected by a fatty sheath called myelin. This sheath acts as insulation in the same way a plastic coating insulates an electrical wire. And, like other types of electrical insulation, myelin allows electrical signals in your brain to travel more rapidly and keeps the signal traveling on target down the length of the axon.

Neurons communicate with each other chemically via a small space, called a synapse, between the axon of the sending neuron and a dendrite of the receiving neuron. When the sending neuron has been activated or “turned on,” it releases chemicals called neurotransmitters from small vesicles at the end of its axon. These chemicals enter the synapse and then latch onto openings called receptors on the dendrite of the receiving neuron like keys in a lock. If enough receptors are keyed, the receiving neuron will fire . . . which triggers another neuron . . . which triggers another neuron in a domino effect. Now your brain is communicating with itself! Depending upon which network of neurons is firing, that communication may be sending signals to your arm to pick up the telephone; it may be amplifying the aroma of fresh-brewed coffee in the morning; or it may be retrieving the memory of a moonlit night in Aruba.

The Synapse Between Neurons Is Where Cell Communication Occurs

When you learn something new or form a new memory, new connections are made between neurons. The act of learning can actually create new dendrites and new connections. In other words, learning literally changes your brain! The more you learn, the richer and denser your “neural forest” will become. If you revisit those memories or bits of learning, you'll increase the speed and strength of these connections. It's like building highways between cities.

The more people need to get from New York to Boston, the more highways will get built and the wider they'll become. Likewise in the brain; if you connect two pieces of information, your neurons will build a road. If you use that road often, your brain will turn it into a superhighway. In addition to helping with learning and memory, these mental superhighways can significantly aid the process of creative thought, which is after all our ultimate goal. Now that we know the building blocks of the brain, let's take a tour around the parts of your brain that are most important to the process of thinking and acting in novel and creative ways.

WHERE MEMORIES ARE STORED

A memory is not stored in one specific location in the brain. Parts of the memory are stored in different locations; for instance, when you remember a summer evening from your childhood, the smell of fresh-mown grass is stored in one location, the feel of grass beneath your feet in another, the sight of fireflies dancing in another, and the memory of joy in yet another location. Because all of these pieces of the memory are connected by a network of neurons, when one piece of the memory is called up, the connections for the whole memory will fire and you will experience the gestalt of the memory.4

Geography of the Brain

Just to orient ourselves, we'll take a quick look at some basic brain geography. Let's lay the foundation for our understanding of the brain by looking at the various hemispheres and lobes.

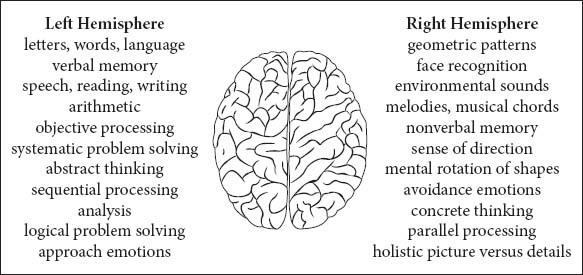

The Right and Left Hemispheres

The brain is divided into two halves—the right and left hemispheres— which are connected by a large tract of neurons called the corpus callosum that allows communication between the two halves. Neurologists have long known that each hemisphere controls the opposite side of the body (so if you want to raise your right hand, it is your left hemisphere that sends the order); however, it was not until the middle of the last century that we learned the hemispheres are actually two complete brains, each with its own personality, likes and dislikes, and skills.

In the 1960s, Nobel Prize winner Roger Sperry and his associate Michael Gazzaniga conducted a set of experiments on several patients who had split brains. Their corpus callosa had been surgically severed in an effort to control life-threatening epileptic seizures. These patients were left with two brains that often had conflicting ideas. For example, the left brain of one patient named Paul wanted to be a draftsman, while the right brain wanted to be a race car driver. Another patient caught himself trying to hit his wife in rage with the right hand (controlled by the left hemisphere) while the left hand tried to protect her.5

These split-brain patients were not merely curiosities; they provided a great volume of information on the specialties of each half of the brain. You've no doubt read in the popular press that the right brain is specialized for creativity. Well, that isn't exactly true. Both halves of the brain are necessary for truly creative work. However, thanks to Drs. Sperry and Gazzaniga and others who have studied split-brain patients, we now know much more about the contributions of each hemisphere to the creative process. We'll talk more about the right and left hemispheres in later chapters.

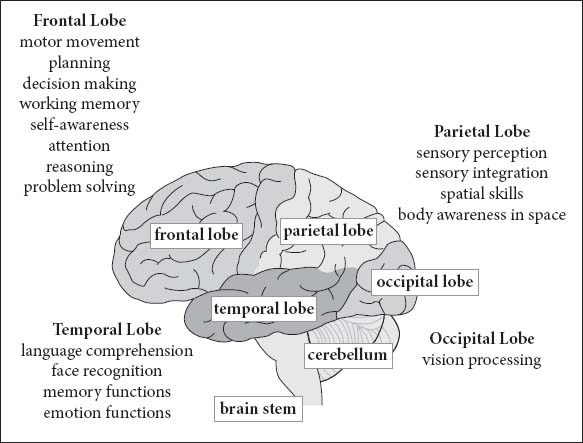

The Lobes of the Cerebral Cortex6

Each hemisphere of the brain is covered with a thin layer (about the depth of three dimes stacked on top of each other) of neuron cell bodies. This thin layer is called the cortex. The cortex of the human brain is wrinkled to provide more surface area. The bulge part of the wrinkle is called a gyrus, and the creased part is called a sulcus. Surprisingly, most of us have wrinkles in basically the same locations in our brains. In fact, the major wrinkles are so predictable that scientists have named them and use them as landmarks in the brain.

The cerebral cortex is divided into four different regions called lobes. Lobes in the more rearward parts of the brain (the temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes) are primarily devoted to processing sensory information coming in from our five senses and storing long-term memories. The frontal lobe is divided functionally into two parts: part of it directs motor movement, and another part—the prefrontal cortex (PFC)—is the center of higher-order thinking processes, such as conscious decision making, planning for the future, and self-awareness.

The neuron cell bodies of the cortex have a grayish appearance. These are the “little gray cells” made popular by Agatha Christie's famous sleuth Hercule Poirot. Beneath the thin cortical layer are the axons that connect the neurons to each other. Because they're coated in the fatty myelin sheath, they have a lighter appearance (and are, therefore, referred to as “white cells” or “white matter”). Nestled in the white matter deep in the brain are some additional groupings of neuron cell bodies. These groupings are often referred to as “subcortical structures,” and they are important for processing information from our senses, our emotions, and for forming memories.

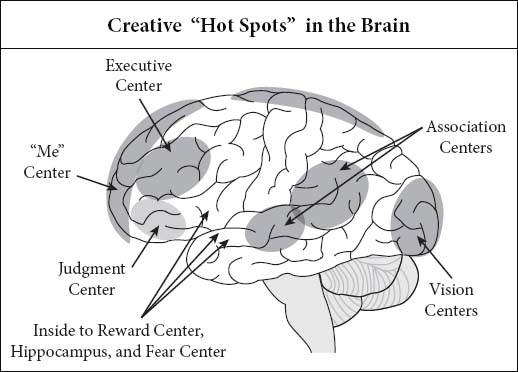

Let's get a little more specific now and look at a few areas that are important for creative thought and behavior. There is, of course, no “creativity” center in the brain. This is because creative cognition is a complex mental phenomenon that involves multiple sequential acts that utilize widespread circuits throughout the brain. In fact, many complex mental functions do not appear to reside in a specific location but are instead spread among richly connected constellations of neurons located across the brain.7 Although we are still learning about these networks of neurons and the mental functions for which they are responsible, we can with some certainty identify a number of brain regions that are important to the various stages of creative thought. (You'll learn more about those stages in the next chapter.) Here, then, are some brain landmarks that appear to be “hot spots” for the networks associated with creative thinking. Remember, however, that no area of the brain works alone but is dependent upon other areas with which it is connected.

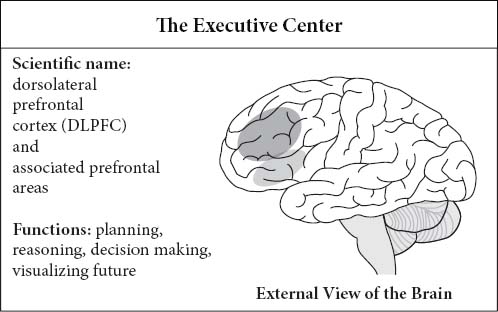

The Executive Center

The first stop on our tour is the executive center, which is composed of the anterior and lateral (front and side) regions of the prefrontal cortex and some highly interconnected regions of the medial prefrontal cortex, including the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).8 This executive part of the brain is in charge of planning, abstract reasoning, and conscious decision making. As in corporate structure, this is the “boss” of the brain. Other regions report either directly or indirectly to the executive. However, like all busy executives, it does not receive “raw” information but rather summaries of what's going on. Most of what reaches the executive center has already been reviewed and edited by “middle management” regions. Lots of information gets weeded out downstream and never makes it to the executive's desk. Therefore, though the executive has final say over decisions, these decisions may be based on summaries of information that are incomplete, erroneous, or biased.

Your working memory is controlled by the executive center. Sometimes called short-term memory, working memory is the ability to hold in mind several different pieces of information for a limited time (such as the phone number you just looked up or the stops you need to make on the way home from work) and to manipulate that information to solve problems.9

The executive center is important for virtually all aspects of creativity.

- It's crucial to “problem finding,” in which you determine new areas of venture that are ripe for change.

- It's necessary for “thinking through” these problems to come up with appropriate solutions.

- It's also crucial for being able to break away from one way of looking at a problem in order to see it from a different perspective. The ability to take different perspectives is, as we will see in later chapters, one of the most important skills for creative thinking.

- Finally—and this is really important for your creative growth—the executive center decides when to step out of the way and let lower-order areas of the brain have center stage to present their ideas. If you have an executive that finds it necessary to micromanage the rest of the brain, you'll compromise your ability to come up with creative ideas. An effective executive is open to ideas from lower-level management. Likewise, an effective executive center can confidently delegate responsibility to other parts of the brain.

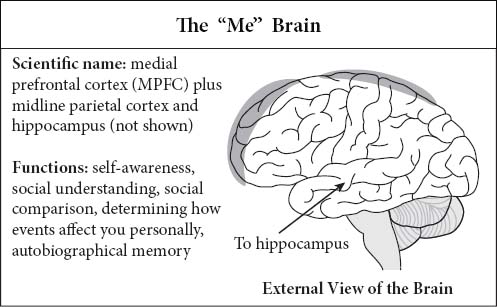

The “Me” Center

The “me” center also resides primarily in the prefrontal cortex and consists of brain structures located along the midline of the prefrontal and parietal cortices. This part of the brain deals with self-awareness, emotions, and the awareness of what others are feeling.10 Being able to take the perspective of others and to imagine how they may be seeing you is accomplished in this area of the brain. This part of the brain tends to be active when you're not involved in deliberate thought (in other words, when your mind is “at rest”). The “me” center sends information about the self and the social environment to the executive brain to be used in decision making, and, as such, is one of the “middle management” centers.

The “me” brain is important for creativity in the following ways:

- It mediates your self-expression.

- It allows you to take another person's perspective, which may be important in writing, art, interpersonal, and business creativity.

- It's active when you're daydreaming or fantasizing, both of which are helpful to creativity.11

Self-awareness can, however, interfere with other aspects of creativity. Therefore, there are times when you'll want to turn the volume on this “me” center down.

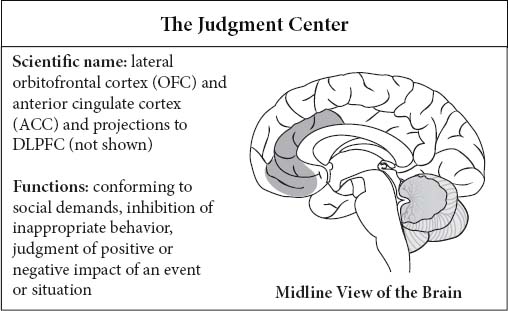

The Judgment Center

Our final stop in the frontal lobe is the judgment center of the brain. Judgment is actually a circuit between the executive center and several other structures in the prefrontal cortex, including the orbitofrontal cortex or OFC and anterior cingulate cortex or ACC.12 This part of the brain compares our actions to internalized standards of behavior and sends out alarm messages when we're out of line. Scientists first learned about the function of this part of the brain through the strange case of Phineas Gage, a New Hampshire railroad worker. One day in 1848, Gage was tamping a charge of dynamite into a hole with a large iron rod. The dynamite exploded driving the iron tamping rod through the side of his face, destroying an area of his frontal lobe. He survived the accident, made an excellent recovery, and lived another thirteen years. However, personality changes were marked, including a tendency toward profanity and an inability to control his “animal tendencies.”13 In other words, his ability to make good judgments was impaired. Scientists have since identified a “disinhibition” syndrome associated with damage to the orbitofrontal cortex (the area of the brain just above your eyes) that includes poor judgment, inappropriate speech, emotions, and sexual advances.14

The judgment center is also important in determining whether an event or situation will have a positive or negative impact for you. It is part of middle management, sending filtered information about appropriateness to the executive center.

The judgment center is important for the evaluative aspects of creativity. Once you've come up with a creative idea, you need to determine whether the idea is appropriate. You also need to evaluate a creative project on an ongoing basis as you bring your creative idea to fruition. However, because the judgment center acts as a filter, there are stages in your creative process when you need to turn down its volume and allow more ideas—even those that will later be determined to be bad ideas—to feed forward into conscious awareness.

The Reward Center

The reward center of the brain includes neural projections to a small cluster of subcortical neurons called the nucleus accumbens.15 When this center is turned on, your self-confidence soars and you feel euphoric. Animal studies show that given a choice between stimulating this reward center or eating, mice will choose to turn on the reward center (they will actually starve to death in order to get this stimulation).16

The reward center is important for creative motivation. Research on motivation is unequivocal in finding that creative activity that is linked to internal or “intrinsic” rewards is of higher quality than that motivated by external rewards.17 The reward center also affects the filtering mechanisms of the brain. Activation of this center allows more ideas and information to feed forward from the association centers in the rear of the brain (see below).

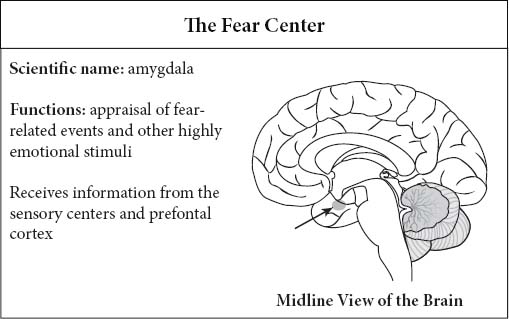

The Fear Center

Here's how fear basically works. First your senses take in information about the environment. This information is sent to a small subcortical almond-shaped structure called the amygdala (Greek for almond). The amygdala determines whether there's a potential threat and, if it detects threat, it sends a message to your body that releases adrenalin, prepares you for fight or flight, and leaves you feeling anxious or fearful, depending upon the degree of danger. The same information is also sent to the executive center, which can turn off the alarm if the threat is perceived to be false.18 Fear is important for survival; so when the amygdala is active, your thought processes are emotionally hijacked and your ability to think creatively is diminished.19

Although fear and anxiety are necessary for survival, they are detrimental to creativity, so learning to control the fear center of the brain is important to enhancing your level of creativity.

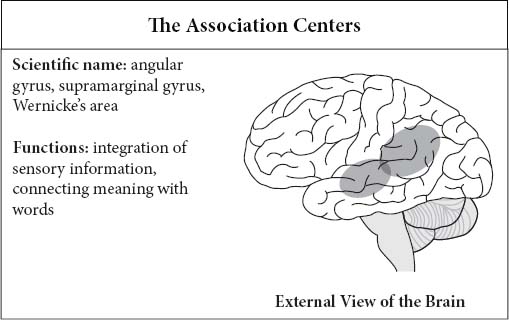

The Association Centers

The association centers in the rear of the brain (temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes) pull together information that is called for by the executive center or that is brought up spontaneously during unplanned or unstructured thought. They integrate sight, sound, smell, and touch to form meaningful experience. These centers have direct connections to the executive center in the prefrontal lobe.20

Of course, the ability to make associations is fundamental to creativity; therefore, the functioning of the association centers is important to creativity in the following ways:

- They allow information from distant parts of the brain to come together.

- They appear to be involved in our ability to take knowledge about one concept and apply it to another (in other words, our ability to use metaphors).21

- They act as an internal research-and-development department that produces both novel and mundane combinations of stored and perceived material.

It is of interest that when researchers examined Einstein's brain (certainly one of the most creative brains ever to inhabit a human body), the biggest difference found between his brain and so-called normal brains was in the area of parietal association (one of our association centers).22

The brain centers that we've just discussed are “hot spots” for creative thought and activity. Many of them are highly interconnected. Also, each of these brain centers may participate in multiple brain networks. Just as you may at any given time participate on several teams (say, a project team at work, a committee for your community charity, as well as a tennis team at your local health club), these brain centers may participate in multiple neural networks that perform different functions, such as feeling emotion, learning new information, visualizing the future, or coming up with creative ideas.

When you activate different brain centers, you change the way you access information both from the environment and from your own personal memory stores. Here's an example. Say you're in Rome standing in the Piazza della Rotonda. If your fear center is activated, you may look toward the Pantheon and see a structure that can protect you from danger. If your reward center is activated, you'll likely look at the Pantheon, bring up all the information you've learned about its past, and see it as an architectural and historical marvel. Your perspective is different depending upon what parts of the brain are firing. Brain activation patterns are, likewise, instrumental in how you formulate creative thoughts and how likely you are to implement your creative ideas.

Now that you're armed with relevant knowledge about the brain, it's time to learn how to use different brain activation patterns—the CREATES brainsets—to increase your creative ideas and productivity. So let's get creative ...