7

7

Thinking Divergently: Accessing the Connect Brainset

Ideas rose in crowds; I felt them collide until pairs interlocked, so to speak, making a stable combination …

—HENRI POINCARÉ1

WHILE THE ENVISION BRAINSET allows you to play out ideas, all within the safety of your mind, the connect brainset allows you to generate multiple ideas without concern about how they will play out. When you access the connect brainset, one idea leads to another and another.2 Your brain becomes an idea-generating machine.

Defining the Connect Brainset

You'll notice several things happening as you learn to access the connect brainset. First, you'll start thinking divergently rather than convergently. Divergent thinking is a type of cognition in which you see many possible answers to questions and problems. In fact, you will risk becoming overwhelmed with possibilities for creative innovation! Second, you will make connections between disparate objects and concepts; these unusual associations will lead to more novel and original ideas. The result? You will find yourself becoming energized and excited about working on your creative problem.3

In addition to the qualities of divergent thinking, making unusual associations, and intrinsic motivation, the connect brainset shares three important characteristics with both the absorb and the envision brainsets. As with absorb and envision, when you access the connect brainset the censor in your brain gets to take a break; this allows more ideas to make it through the automatic filtering system into conscious awareness (what we called “cognitive disinhibition” in Chapter Five). You are attracted to novelty and complexity; just as you receive an internal reward for noticing new or novel aspects of things in the absorb brainset, you get excited about interfacing with previously unexplored and novel ideas in the connect brainset. Finally, as with the absorb and envision brainsets, you suspend judgment in the connect state, especially judgment of your own ideas; thus, when an idea makes it into conscious awareness, you don't direct your attention toward evaluating it. Instead, you direct your attention toward the generation of the next idea, resulting in an array of possible solutions to your creative problems.4

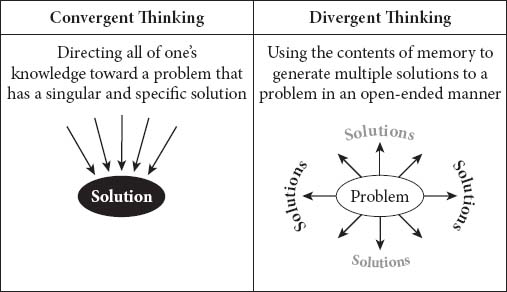

Divergent Thinking

Divergent thinking is one of the hallmarks of the creative mind. Many researchers who study creativity refer to the propensity to think divergently as a measure of trait creativity or potential creativity.5 It is sometimes described as the “other” way of thinking. But if divergent thought is the “other” way, what is the so-called “normal” way of thinking? That would be what researchers call convergent thinking. Let's look at the difference between divergent and convergent thought processes.

Convergent thinking6 is the type of thinking you do when you access the contents stored in your brain (including knowledge and memories) to come up with the one correct answer to a well-defined problem. You are already familiar with convergent thinking, as it is the form of thought needed to solve questions on standardized tests such as the SAT Reasoning Test. Convergent thinking is also the basis for most questions on high school and college exams. Consider the following sample question from an SAT test in which you are asked to fill in the blanks with the appropriate words:

They were not _________ misfortune, having endured more than their fair share of _________.

a) cognizant of … calamity

b) superstitious about… prosperity

c) jealous of… success

e) unacquainted with… adversity7

Now if you think convergently, and if you have a decent vocabulary, you fill in (e) and go on your way because (e) is the “right” answer. Being able to think convergently is an important skill; and it is also important in the creative process, as we'll discuss at length in Chapter Eight. However, convergent thinking limits your thought processes by assuming that there is one right answer to a problem. Rather than exploring multiple options, the convergent thinker will search for the one salient and correct solution.

Divergent thinking, in contrast, is the propensity to generate multiple solutions to a single problem or dilemma.8 You think in terms of possibilities rather than absolutes. Whenever you find that you're facing an open-ended problem that does not have one absolute right answer, you will find your divergent thinking skills to be invaluable. Of course, people who tend to be divergent thinkers often view all problems as open-ended and consequently generate multiple solutions even when the rest of the world is seeing the problem through convergent eyes.

As an example, let's return to our test question.

They were not _________ misfortune, having endured more than their fair share of _________.

a. cognizant of … calamity

b. superstitious about … prosperity

c. jealous of … success

d. oblivious to … happiness

e. unacquainted with … adversity

We already noted that (e) is the correct answer (convergently). However, if you tend to think divergently, answer (e) does not jump out at you. Indeed, as a divergent thinker, you will approach the problem differently. Here's the thinking process described by one of my very bright divergent-thinking students:

At first I thought, (e) looks like a good answer, but (a) could also be correct; some people who have experienced calamities aren't really cognizant of their misfortune because they're in denial. And then again (b) could be the answer because prosperity might make some people less superstitious about misfortune since they haven't really experienced true misfortune and would therefore not be developing superstitions to ward it off. Or (d) could be the answer; happiness could in some cases be considered a misfortune because when you're happy you may become too content and then you might miss out on opportunities because you're not looking for them, or you may not see adversity coming at you.9

In other words, what is very clear-cut to the person who tends to think convergently, is anything but clear-cut to the divergent thinker who prefers complexity and generates explanations that encompass each of the possible answers to the question. The divergent thinker has considered the problem from all angles and made connections between the question and each of the potential answers. He has now spent four times as long on the question as the person who is tuned to think convergently, and his likelihood of choosing the “right” answer is still no better than chance. Instead of eliminating some of the answers to improve his chances of making the correct choice, his divergent thought processes have brought all answers into the realm of possibility.

Does this sound familiar? If you're primarily a divergent thinker (if your score on the quiz from Chapter Two indicated you prefer the connect brainset), you may have had a lot of trouble with convergent tests such as the SAT. You may have been considered an underachiever in school precisely because most scholastic tests are based on convergent thinking principles.

The divergent thinker sees a rich tangle of possibilities in every situation. The divergent thinker is often highly creative. However, we live in a convergent-thinking world for the most part. And if you're a divergent thinker who spends a great deal of time in the connect brainset, you may feel that others don't understand you. In fact, many of the highly creative individuals that I work with attest to feeling like a round peg in a square hole. (One screenwriter actually related that he felt like “an octagonal peg with conical appendages in a square hole”!10) If you feel like this—and the connect brainset is your mental comfort zone—we will address your problems in the next two chapters where you will learn some convergent-thinking skills. However, right now we need to convince the 60 to 80% of you who find divergent thinking uncomfortable11 that you can increase your creative capacity by learning to access the connect brainset during creative problem solving (just don't do it when you're taking the SAT!).

Speaking of creative problem solving, before we continue let's take a look at three different types of problems that can be solved creatively. These include reasonable (or logical) problems, unreasonable (or illogical) problems, and ill-structured (or open-ended) problems.12 When working on a creative problem, it's helpful to understand the kind of problem you're facing before you try to develop a strategy to solve it.

First there are reasonable problems (sometimes also called logical problems). These are problems that have a single endpoint as their solution, and you can use logic or reason to reach that solution. For these problems, there's some sort of protocol or road map you can follow to get to the solution. Mathematical equations are reasonable problems, as are many real-life problems, such as balancing your checkbook, finding a book in a specific library, or constructing a child's bicycle from a kit; for all of these problems there is a single correct endpoint or solution as well as a protocol you can follow to get there.

The problems on the SAT tests are reasonable problems, and they can be solved using convergent thinking. However, though reasonable problems always have a single endpoint and a logical road map for getting to the solution, there may be more than one protocol or road map you can follow to get to that endpoint. For instance, if you wish to go from Boston to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Museum is your one correct endpoint. Yet there are multiple paths you can take to get there: you can get in your car and drive down I-95 or you can drive down I-84. You can also go to Logan Airport and get on the shuttle to LaGuardia, you can take Amtrak, or you can (not recommended without an insurance policy) take one of the “dollar” buses that run between the two cities. Even though there are multiple ways to reach the museum from Boston, the problem is still reasonable because there is a single endpoint and set precedents for how to get there.

Some reasonable problems are very difficult, but they can still be answered using reason and established protocols. Here are a couple of examples: (1) given the diagnostic criteria for depression, determine the prevalence of depression worldwide, or (2) determine if there are additional planets in the solar system. There is one correct answer for the incidence of depression, and there is one correct answer for the number of planets … and there are specific methods for finding these answers; therefore, they are reasonable problems.

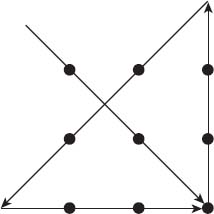

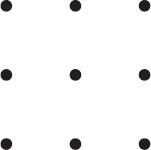

Second, there are unreasonable (or illogical) problems. These are problems for which there is one right solution or endpoint but for which there are no road maps or protocols to follow to reach the solution. These problems include what are often called “insight” problems. That is, you typically need a flash of insight—the “aha!” experience—to solve them as they can't be solved with logic. Here's one of the most popular insight problems. The goal is to connect all of the dots using four straight lines without picking your pencil up off the page.

As with other insight problems, this one cannot be solved by logic. It requires “thinking outside the box” literally and figuratively. (If you're not familiar with the nine-dot problem, you can find the solution toward the end of Chapter Seven.) Insight solutions arrive via the spontaneous pathway in a sudden burst of recognition (like “getting” a joke). You never feel like you're getting warmer to the solution until it bursts upon you. Many creative problems in the sciences fall into the unreasonable category; for these problems there is a correct solution, but no roadmap as to how to get there. As Einstein remarked, “There is no logical bridge from experience to the basic principles of theory.”13

Finally, there are ill-structured or open-ended problems. These problems have more than one possible solution, and there are no clear guidelines for how to get to a solution or endpoint or even how to tell when you've arrived at a suitable solution. Many creative problems are ill-structured and open-ended. For example, say you are Tchaikovsky and Czar Alexander III has commissioned you to write the march for his coronation; where do you begin? Or you are Frank Lloyd Wright and you want to build a house that blends into the landscape; what roadmap do you follow? Or you are Aaron T. Beck and you know that the current treatments for depression are not very effective. You want to improve them; how do you proceed?

Ill-structured or open-ended problems are precisely the kinds of problems you need to identify and address in order to survive and thrive in our rapidly changing world. Here's the thing: you can't solve ill-structured problems with convergent thinking. You need to access the connect brainset and set those divergent thinking wheels in motion, even if you have to suffer temporary “square peg in a round hole” syndrome to do it!

In the connect brainset, ideas seem to flow and “connect” one to another (hence the name!). People who spend time thinking divergently—and thus in the connect mode—generate more ideas with seemingly less effort than people who dwell in the reason brainset.14 This is called ideational fluency.

Ideational fluency is the production of a large number of potential solutions to a creative problem. This is important because, for the most part, the quality of creative ideas is a function of the quantity of ideas. Not only does common sense dictate that if you produce enough ideas some of them are bound to be good, but research upholds this relationship as well. Extensive research on the lives of musical composers by Dean Keith Simonton of UC Davis indicates that the periods of highest quantity of music production are also the periods of highest quality of creative products. Oh sure, there are a couple of “one-hit wonders,” but for the most part, the more the better.15 Research on divergent thinking problems in our lab also supports this finding: People who produce the greatest number of ideas generally produce the greatest number of high-quality ideas as well (of course, they also produce the greatest number of low-quality ideas, but we'll discuss what to do about that in Chapter Ten. (To improve your divergent thinking skills, see Connect Exercises #1–3).

If you find that you are mentally exhausted by divergent exercises, you are probably thinking too hard. This can happen when you try to approach divergent thinking problems using the reason brainset. (You'll learn more about using reason to solve creative problems in the next chapter.) By relying on your prefrontal executive center to deliberately search for answers for which there is no known pathway or road map (especially under time constraints such as the three-minute time we set on the exercises at the end of this chapter), you may become stuck on a single solution. For instance, one divergent thinking exercise will ask you to come up with as many uses as you can think of for a soup can. When thinking reasonably, people tend to get stuck on seeing a soup can as a container. They will write down uses such as pencil holder, spare change holder, flower vase, water cup, ashtray, and candle holder. They will then go blank. The better way to approach divergent thinking tasks is to have your prefrontal executive send a directive to the rear of the brain where the research-and-development team can go to work and find answers. This entails defocusing attention in the prefrontal part of the brain so that more answers are allowed into conscious awareness.16

The more often you practice solving open-ended tasks such as divergent thinking exercises, the better able you will be to achieve the connect brain state. Soon you will find yourself mentally energized by them, and you will find yourself thinking divergently even when you're not engaged in the exercises.

If your mental comfort zone is either the reason or the evaluate brainset, you may feel that the divergent thinking exercises are “impractical” or “unrealistic.” Because there are a number of individuals who don't see the value in divergent thinking at first, I often start divergent thinking training with a practical example from real life. Here, for instance, is a task based on something that actually happened to one of my colleagues:

You are scheduled to give expert testimony before a Congressional committee in 10 minutes and your testimony will be broadcast on C-Span and recorded for posterity. You look down and notice your fly is broken and your slacks won't zip up. What do you do? You have three minutes to generate responses.

Here's a response of a student who had identified with the reason brainset:

First, I would remove the pants and try to fix the zipper. It's easier to fix a stuck zipper when the pants are off. If the zipper was still stuck I would ask around and see if anyone had one of those travel sewing kits. If so, I would go to the men's room and try to sew the fly closed. If no one had a sewing kit, I would ask the committee chairperson if she could delay the proceedings for a moment as I was having a “wardrobe malfunction.”17

Reasonable indeed. And this individual was pretty proud of having thrown the humorous reference to “wardrobe malfunction” into the response. Compare this response to the following response from an individual who identified with the connect brainset:

- Find a sewing kit (Congress probably has one that cost the taxpayers several thousand dollars)

- Put the slacks on backwards (no one will see your back)

- Glue the slacks shut

- Use Velcro

- Staple the slacks

- Use a piece of gum to stick the fly together

- Take the slacks off and speak in your underwear

- Ask a short Congressman to stand in front of you

- Tear a two-inch-wide strip out of a magazine and wrap it around the arm of your jacket and tape it in place. People will be so curious about your armband that they won't look at your pants

- Make a joke about how Congress has raised your taxes so much you can't afford a decent suit

Notice that the first respondent approached this problem as though it were a logical problem, having a single solution, namely, mending the broken pants somehow (hence the search for a sewing kit; if one can't be found, there will have to be a delay in the proceedings). The second respondent—who is thinking divergently—treats the problem as an ill-structured or open-ended problem to which there may be a number of solutions. Notice also that the second respondent did not censor any of his responses, even though a couple of them were clearly not very practical. In fact, by generating some off-the-wall responses, he was increasing his ideational fluency through the use of humor. (Luckily my colleague who actually had this experience seems to be a divergent thinker. He was able to generate several ideas for dealing with the broken fly. He reports that a few well-placed staples did the trick, and further, that every Congressman's office has a stapler. Crisis averted!)

BRAINSTORMING

If the divergent thinking exercises sound like brainstorming, it's because brainstorming is actually a type of group divergent thinking. Brainstorming was first described by Alex Osborne in 1953, and promoted as a team creativity technique for businesses. As with divergent thinking, the goal of brainstorming is to generate as many ideas as possible without judging them. Everyone on the team shouts out ideas to a specified problem while one team member writes down the ideas. Later the team looks over the ideas that have been generated and begins the process of eliminating some and building off of or combining other ideas.18

However, research on brainstorming shows that more quality ideas emerge if individuals brainstorm alone and then bring their best ideas to the table for the group to assess. That's because even though the process is supposed to be nonjudgmental, individuals with lower status in the group may still be wary of shouting out ideas that their superiors could judge as foolish. In order to counteract this problem, a newer technique called brainwriting has been introduced into group divergent thinking sessions. In this technique, each member of the group generates three to five ideas on an index card. The cards are then passed anonymously to the group spokesman who introduces each idea for the group to explore. Brainwriting can also be adapted for use with groups on the Internet.19

The point is that the more ideas you can come up with, the more likely it is that at least one will be a quality idea that can solve your problem. The take-home message from the broken fly incident is this: try to view every problem in life as an ill-structured or open-ended problem for which there are multiple potential solutions. Try to think divergently and generate multiple solutions—even if some of them seem “stupid” or “impractical.”

Einstein said: “The formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution … To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old problems from a new angle … marks real advance in science.”20 You can use divergent thinking to find or define a creative problem as well as to solve one (see Connect Exercise #3 to practice problem finding).

Finding Unusual Associations

Why is it that unique and original ideas for both creative problem-generation and solution-generation will surface when you're in the connect brainset? Part of the answer is that there is a spread of activation in both the semantic regions of the brain that store the meanings of words and the phonological regions that store the sounds of words. At the same time, the volume on the censor that limits the spread of semantic and phonological activation is turned down. This means that the connections will be opened between words and concepts that are more remotely associated in the brain than would normally occur.

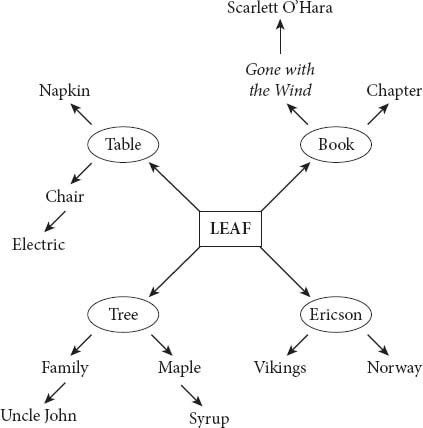

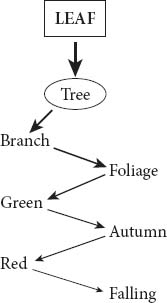

Word association tasks are often used to demonstrate how a broad associational network can bring to mind a wealth of data which can be used in the creative process.21 Here is an example from a word association task from my early creativity studies at Harvard. Ordinarily, when given the word prompt “leaf” and asked what words come to mind, subjects respond with “tree” words. Following is a diagram of a typical response.

“Tree” is the most common associate to the word “leaf.” And “tree” opens an associational network like the one shown above. The thickness of the arrows demonstrates the strength of the associations. Stronger associations will come to mind more quickly, while weaker associations will come to mind only when the strong associations have been exhausted. Thus, this subject responded with the word “tree” very quickly and then the responses took a bit longer until the spread of activation ended and the subject could come up with no further words associated with “leaf.”

Now here is the diagram of the response of a highly creative subject22 whose mental comfort zone would likely be in the connect brainset (although I tested her before I had developed the CREATES model). She demonstrated a much broader spread of activation to the word “leaf:”

Notice that her responses included not only associations to different meanings of the word “leaf,” but also associations to the sound of the word (as in Leif Ericson). This diagram is evidence of a mild state of disinhibition, where many different words clearly not directly associated with “leaf” were allowed access to conscious thought. Further, the strength of the associations was about equal, so the reaction time for all of these words was very rapid, each following the response before it without a pause.

Many of these responses may seem somewhat inappropriate (who would ever associate Scarlett O'Hara with a leaf?). Nevertheless access to this broad associational network is enormously beneficial to the creative process, which is dependent upon the ability to connect disparate pieces of information to come up with novel ideas. One of the most powerful ways to come up with creative and innovative ideas is to make a habit of forming connections between ideas and objects that are seemingly unconnected. (See Connect Exercises #4 and #5 for fun word games that will help you activate associational networks and facilitate connection making.)

Motivation or Goal-Directed Activity

Scholars and business executives used to see word games (like those in Connect Exercises #4 and #5) as time wasters rather than serious brain work. However, thanks in part to the findings of neuroscience (and thanks in large part to the success of companies such as PIXAR, where animators get to design their own huts and caves as office spaces), the serious value of “play” and “games” is beginning to receive recognition.23 Play and games, as it turns out, increase activation in the very parts of the brain associated with creative thinking. Playfulness also increases your motivation to pursue and persevere in a creative project by turning on your internal reward system.24

Eating chocolate, receiving an unexpected gift, or having a good laugh can make you more creative (temporarily). I found unscientific evidence for this idea one semester when I gave an exam in my creativity course. On the occasion of one midterm exam, I brought in a large bag of chocolate candies and passed them out before the exam, while students received no unexpected candy before a second midterm. Into each exam I slipped a question that tested students’ ideational fluency. I found that more ideas were generated during the “chocolate” exam than during the “no-chocolate” exam. Now it's hard to tell whether students were more creative in the chocolate exam because they were on a sugar high, or because chocolate acts as a stimulant (which it is), or because students were pleased that they got something they weren't expecting … or because I wanted the chocolate experiment to work and so I unconsciously made the chocolate exam easier or more fun. (These reasons—and the fact that I didn't get clearance from the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research to run this as an “official” experiment—are why I call my subtle chocolate experiment “unscientific.”)

However, there is also actual scientific evidence that indicates you're more likely to generate a large number of ideas and to make unusual associations when you receive an unexpected reward or when you're in a good mood. Alice Isen and her colleagues at Cornell have studied the effects of positive mood on different aspects of cognition. They've found that people do better on tests of divergent thinking after positive mood is experimentally induced by giving subjects in their experiments an unexpected gift.25 Other studies have found that people score better on divergent thinking tasks after laughter or a good joke. In a large meta-analysis of the effects of positive mood on creativity, Matthijs Baas and his group at the University of Amsterdam found that positive mood significantly enhanced ideational fluency and originality in the bulk of the 102 research studies they investigated.26

Conversely, rapid thinking of the type that's associated with divergent thinking tasks can increase positive mood and other aspects of creativity. In a recent experiment, Emily Pronin of Princeton and Dan Wegner at Harvard ran an experiment with Princeton undergrads in which they were forced to think much more rapidly than normal by reading statements that scrolled across a computer screen at a fast pace. They found that thinking quickly increased positive feelings. It also increased some other effects, including feelings of creativity, feelings of power, higher self-esteem, and a heightened sense of energy.27 (See Connect Exercise #6 to practice a rapid-thinking exercise.)

A side effect of pairing this upswing in mood with a creative project in the connect brainset is that your motivation to work on and complete the project is enhanced. Positive mood and the self-esteem that accompany it lead to an increase in agency—or the belief that you have the power to overcome obstacles and achieve your goals.28

Psychologist Norbert Schwarz of the University of Michigan and his associates suggest that positive mood allows for more divergent and playful thinking because it signifies that all is well. When you aren't worried about threats in your environment or how you're going to put the next meal on the table, you have the leisure time to devote to exploration of new ideas. You can play around with alternate solutions to problems and make playful connections between ideas because your mind is not occupied with survival.29

We've now seen that the connect brainset involves divergent thinking, unusual associations, and motivation in the form of internal rewards and positive mood. There are exercises following this chapter that can help you activate this set of creativity-enhancing factors. However, there are also some other methods of entering the connect brainset. Neurologist Alice Flaherty from Harvard Medical School and I found that subjects in a study we have been running increased their divergent thinking scores and had increased energy and positive mood after two weeks of exposure to 10,000-lux bright light. (This is the same intensity of light that is used to treat seasonal affective disorder.) Although we haven't tested this, our study would suggest that spending more time outdoors in the sunlight (with sunscreen of course, which doesn't interfere with the therapeutic effects of bright light) might have the same effect on divergent thinking.30

Speaking of the outdoors, other research has investigated the effect of surroundings of natural beauty on cognition. As it turns out, spending time in areas of beautiful scenery—such as the ocean, the woods, or in the presence of a beautiful sunset—releases endogenous opioids that increase positive mood and decrease cognitive inhibition,31 making the connect brainset easier to utilize.

You can also use any of the rewards on the Small Pleasures list you made in Chapter Two (Cluster Two, Exercise #9) to induce a positive mood. However, the results of experiments seem to indicate that simply being in a good mood does not evoke divergent thinking and the connect brainset; rather you have to change your mood in a positive direction to get this effect. Listening to upbeat music, hearing a good joke, and engaging in physical activity such as dancing can also be beneficial in elevating your mood.

Strangely, you would think that taking drugs that have been deemed “uppers” would also do the trick; however, studies that have looked at the way amphetamine affects divergent thinking have found no significant positive or negative results. Perhaps this is because of the dose-dependent effect of amphetamine-type drugs. In very small doses, amphetamines can lower cognitive inhibition (this, according to our model should enhance divergent thinking); however, in slightly greater doses, amphetamine drugs increase inhibition (which should have a negative effect on creativity). In fact, there is a growing what-if-Einstein-took-Ritalin public debate about the effect of amphetamine-based treatments for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on children's creativity.32 There is a lack of research on the effects of caffeine on creativity (although one study found that artists tend to use more caffeine than members of a control group). However, the dose-dependent effects of this drug on other aspects of cognition have been studied; small doses have a beneficial effect while higher doses hamper effective thinking.33 The bottom line on “uppers” is that science hasn't provided evidence to support their use in enhancing associational thought. There appears to be a dose-dependent response to such substances, such that minor variations in the dose may restrict rather than enhance creative thought.

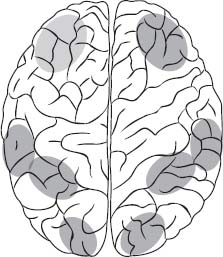

Neuroscience of the Connect Brainset

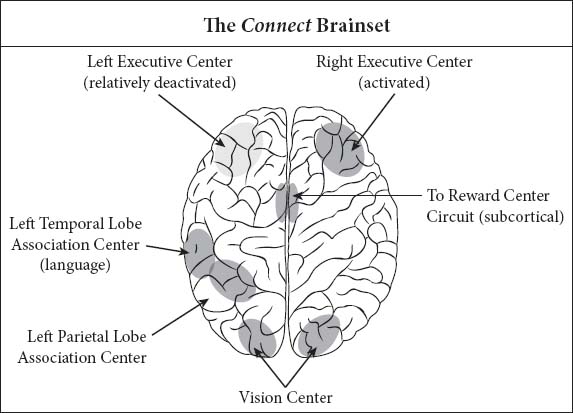

What does your brain look like when you access the connect brainset? The connect brainset appears to combine elements of both the spontaneous and the deliberate pathways described in Chapter Four. On the one hand, there is considerable evidence for an increase in alpha wave coherence in the prefrontal lobes when individuals who score high in divergent thinking skills engage in divergent thinking problems.34 This suggests a defocusing of attention and a mild deactivation of the lateral executive areas involved in the deliberate pathway.35 On the other hand, the connect brainset does not reflect a completely spontaneous state in which ideas spring unbidden into mind. It is, rather, a state in which you are actively searching for connections in a semi-spontaneous manner.

Kalina Christoff and her colleagues at the University of British Columbia have proposed that there is a type of creative thinking lying somewhere between the deliberate and spontaneous pathways.36 I believe that the connect brainset may embody this creative thinking pattern. This in-between-state interpretation would account for some seemingly contradictory findings that show increased alpha coherence in prefrontal areas on the one hand (suggesting deactivation), but increased prefrontal activation relative to resting state in other studies.37

A second finding is that there is an increase in ratio of right-to-left hemisphere activation of the prefrontal cortex in the tasks that we've associated with the connect brainset. For instance, the right prefrontal cortex increases in activation when subjects are asked to find associations between unrelated words or when they are asked to incorporate a group of unrelated nouns into a short story. This makes intuitive sense, because activation of the right hemisphere is known to evoke a broad attentional focus, whereas left hemisphere activation evokes a narrowing and focusing of attention. Broadening of attentional focus would lead to a wider ranging search for potential connections between ideas. Right hemisphere activation has also been shown to facilitate the processing of distant semantic associations.38 (So Daniel Pink may have been on target when he said in his 2005 best-seller A Whole New Mind that “right-brainers will rule the future”!39)

Finally, the connect brainset is characterized by activation of the associational centers, just as we would expect from a state of brain that is devoted to making associations! These areas are clearly activated during association exercises, especially on the left side of the brain where semantic information is stored.40

The main connect brain pattern then consists of defocused attention (as demonstrated by increased alpha wave coherence in the prefrontal lobes), preferential activation of the right hemisphere prefrontal area, and activation of the association centers in the temporal and parietal lobes (especially in the left hemisphere). What I am suggesting is that the relative deactivation of the prefrontal lobes in the left hemisphere disinhibits the actions of the right hemisphere to allow for a broadening of attentional focus and the greater activation of associational areas.

Some corroborating evidence for the disinhibitory explanation comes from an interesting case reported by neurologists William Seeley and Bruce Miller of UC San Francisco.41 Anne Adams, a scientist and artist, suffered from a degenerative brain condition called primary progressive aphasia that affected the language centers of her brain. As the disease was wreaking devastation to the left prefrontal cortex and part of the left temporal lobe, Anne developed an intense drive to create art. Further, she began expressing unusual cross-modal themes in her art, such as rendering music and mathematics through paint. Somehow, the deficit in the left frontal lobe led to strong creative motivation and extremely creative associations of remotely related concepts through art. Notice also that Anne's cross-modal art expression is reminiscent of the cross-modal experiences of synaesthetes, who “see” music and “hear” numbers (see Synaesthesia and Creativity).

Anne Adams's sudden creative motivation is rare but not unique. Other cases of what's called “sudden artistic output” have been reported after the disease frontotemporal dementia (FTD) strikes the left hemisphere.42 It seems that the deactivation of parts of the left prefrontal lobes by disease allow creative drives that may have been inhibited to come to the forefront. One question that has yet to be answered is whether we all have this creative drive that is currently inhibited by our high-functioning left hemisphere or whether the drive to create is unique to only certain individuals who just happen to contract FTD.

SYNAESTHESIA AND CREATIVITY

Synaesthesia is an unusual condition in which different sensory and verbal systems in the brain seem to be cross-wired. Thus, synaesthetes may “hear” colors, or different words may evoke the sound of notes on a musical scale. Some synaesthetes see letters of the alphabet as colors, so when they read they may be bombarded with a rainbow of colors or musical notes uncontrollably. Synaesthesia runs in families and is seven to eight times more prevalent among highly creative individuals than among the general population. Neuroscientist V. S. Ramachandran of UC San Diego has studied synaesthetes at great length and has found that their brains are wired differently in the left association center (left angular gyrus and supramarginal gyrus).43 This is exactly the region that lights up when people are making unusual associations during creativity testing. (Note that this is also the only part of Einstein's brain that was found to be larger than average.) Back in Chapter One, we mentioned Sarnoff Mednick's theory that the ability to synthesize remotely associated elements of thought into new and useful combinations is the basis of creativity.44 The fact that synaesthetes have unusual brain connections in the association centers of the brain may explain their overrepresentation among creative achievers.

The case of Tommy McHugh may shed some light on this question. Tommy was a construction worker in Liverpool, England, with no stated interest in art or poetry until an event in 2001 changed his life. Tommy then suffered an aneurysm that affected his frontal lobes and required brain surgery to save his life. About two weeks after the surgery, Tommy began to fill notebooks with poetry and to draw hundreds of sketches. Upon returning home, he filled every square inch of wall space in his house with paintings and continues to paint obsessively. He also became interested in sculpting with clay. His desire to be engaged in creative work appeared to be on an obsessive level.45

My connection with Tommy began when Alice Flaherty, the Harvard neurologist with whom I conducted the light therapy study, asked me if I'd be interested in testing Tommy on standard creativity tasks. The question everyone involved with Tommy wanted to know was whether his drive to create was caused by the disinhibition of an innate creative drive or whether it was an indication of a compulsive disorder, similar to what we might see in an OCD patient who has to turn off a light switch over and over again. Unfortunately, we have not been able to scan Tommy's brain since his drive to create began due to the presence of a metal shunt installed to stop the bleeding in his brain (metal can be dangerous in a brain scanner). If we could see his brain, we could tell more about the origin of his continuing desire to paint, sculpt, and write. My sense from communicating with Tommy and observing his work is that he is thoroughly enjoying his new talents and creative drive (this is evidence against the compulsion explanation and for the disinhibition theory) and that his artistic work is continually improving. When asked about his new art-based life in an interview with reporter Jim Giles of Nature, Tommy reported, “My life is 100% better.”46

The damage done to Tommy's frontal lobes appears to have disinhibited both his reward-based motivation to create and his verbal and visual ideational fluency. I would say that he seems to be living in a permanent condition of the connect brainset. I'm happy to report that Tommy's artwork is now receiving international recognition.

When to Access the Connect Brainset

The brain model of the connect brainset is characterized by defocused attention, increased right hemisphere activation, and increased activity in the association areas of the brain. This activation pattern can be helpful any time it would be beneficial to come up with more than one option for creative problem finding or problem solving in your professional or personal life. It will be most beneficial, though, when you're trying to find solutions to ill-structured open-ended creative problems. Remember, though, that you can use it to work on any of the three types of problems: reasonable (logical problems with a single correct solution), unreasonable (illogical problems with one right solution that is not evident unless you “think outside the box”), and ill-structured (open-ended problems for which there is more than one right solution). Finally, try using the connect brainset during the elaboration stage of the creative process, when you need to flesh out an idea or project. There may be more than one direction you could take the elaboration, so why not use the connect brainset to explore?

Caveman #1: I don't understand it, Folg. You failed the standardized test for skinning a saber-toothed tiger. And you seem so bright….

Caveman #2: I don't do well on standardized tests … but have you read my latest work?

In this chapter you've seen that divergent thinking, making unusual associations, and a rise in motivation are all connected to each other and are facilitated by the brain changes modeled in the connect brainset. The connect brainset is the ideal brain state in which to generate abundant creative ideas and get excited about your creative project. But generating ideas is only part of the creative process. It's possible to get stalled in an extended whirlwind of generating ideas but fail to act on them. In the next two chapters, you'll learn about brainsets that keep your creative project moving forward in a positive direction.

Exercises: The Connect Brainset47

Connect Exercise #1: Divergent Thinking: Alternate Uses

Aim of exercise: To improve ideational fluency and divergent thinking skills. You will need a stopwatch or timer, three pieces of paper, and a writing utensil. This exercise will take you nine minutes.

Procedure: Set the timer for three minutes and then write down all the uses for a soup can that you can think of. Don't stop writing until the timer sounds.

Immediately reset the timer for three minutes and write down all the white edible things you can think of on the second sheet of paper. Don't stop writing until the timer sounds. Finally set the timer again for three minutes and, using the third sheet of paper, write down all the consequences you can think of that would occur if humans had three arms instead of two.

When the timer sounds, check how you're feeling. Did the exercise energize you or exhaust you?

Continue to practice divergent thinking exercises every other day by considering alternative uses for other common household objects (examples include a newspaper, a paper clip, or a brick) and other unusual physical conditions (for example, the consequences if humans had six fingers instead of five on each hand).

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one connect token for completing this exercise and one additional token for each time you practice divergent thinking exercises. Additional divergent thinking training can be found at http://ShelleyCarson.com.

Connect Exercise #2: Divergent Thinking: Loquacious Friend

Aim of exercise: To help you generate multiple solutions to an open-ended problem and to improve your divergent thinking skills. You will need a stopwatch or timer, a piece of paper, and a writing utensil.

Procedure: Consider the following dilemma. Your friend Ron always sits next to you during the weekly production briefing. Ron really likes to talk to you, and he distracts you so that sometimes you miss an important part of the briefing. Also many times you don't finish your work because he constantly drops by your desk to talk. But because he's your friend, you don't want to offend him.

- Think of as many ways as you can to solve this problem. Don't judge your answers and try to be creative. Set the timer for three minutes and do not stop writing answers until the timer sounds.

- When the timer sounds, look over your list. Did you write down some ideas that surprise you? Give yourself one connect token in the Rewards section of the journal.

- Try to spend at least 15 minutes every other day purposely thinking divergently about a practical problem (this could be a problem from your own life or one that you make up).

- If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one connect token for completing this exercise and one additional token for each time you practice the divergent thinking exercise. You may want to check out the divergent thinking training program available on the http://ShelleyCarson.com Web site.

Connect Exercise #3: Divergent Thinking: Creative Problem Finding

Aim of exercise: To help you recognize the large potential for creative innovation that exists all around you and to improve your divergent thinking skills. You will need a stopwatch or timer, a piece of paper, a writing utensil, and your journal.

Procedure: Wherever you are (it could be on a subway, in a shopping mall, at your desk at work, or in your own living room), sit down and prepare to write.

- Set the timer for three minutes and do not stop writing until the timer sounds.

- Look around you and list all the objects, situations, or procedures within your current environment that could be improved, changed, or replaced to make life run more smoothly. Be as creative as possible and do not judge any of your ideas.

- When the timer sounds, look over your list. Are there some ideas that you might actually be interested in pursuing? If so, transfer them to your journal in the area for Creative Problems. Write today's date and be sure to include your current location.

If you are using the token economy incentive, award yourself one connect token each time you complete this exercise.

Connect Exercise #4: Activation of Associational Networks: Word Association

Aim of exercise: To practice activating broad associational networks and to increase divergent thinking skills. You will need a stopwatch or timer, a piece of paper, and a writing utensil.

Procedure: Set the timer for three minutes and do not stop writing until the timer sounds.

- Write down all the words that come to mind when you think of the word “spring.”

- When the timer sounds, look at your list of words. Now make a map of your associations similar to the one shown earlier in this chapter using the word “leaf”

- Look at your map. Did words associated with different meanings of the word “spring” come to mind? Take note of your most unusual associations.

You can perform this exercise using any noun as a prompt. If you are using the token economy incentive, award yourself one connect token each time you complete this exercise.

Connect Exercise #5: Activation of Associational Networks Exercise: Degrees of Separation

Aim of exercise: To practice activating broad associational networks and to increase divergent thinking skills. You will need a piece of paper and a writing utensil.

Procedure: Open any book and point to a word. If the word is not a noun, pick the noun closest to the word you chose in the text (note that the noun should not be a proper noun). Write the word down. Make room for three words to the right of that word by drawing dashes. Now open the book to a different page and select another noun. Try to connect the two nouns by using no more than three connecting words. Here's an example using the two random words “fish” and “money.”

![]()

Now try to find two words to connect your nouns. For example:

Finally, try to connect your nouns with just a single word. For example:

![]()

As a variation on this exercise, you can use two nouns suggested by your environment. For instance, if you're driving you can pick words off billboards or signs. This is a great car game to do with kids.

If you are using the token economy incentive, award yourself one connect token each time you complete this exercise.

Connect Exercise #6: Increasing Speed of Thought Exercise

Aim of exercise: To increase your thinking speed, as well as to enhance positive mood and motivation. You will need a stopwatch or timer and a novel that you have enjoyed reading in the past. This exercise should take you around 12 minutes, depending upon your reading speed. The purpose of this exercise is not to read fast; it is to speed up your thinking. So don't concern yourself if your initial reading speed seems slow.

Procedure: Set your timer for five minutes, and open the book. Begin reading at your normal pace at the top of the left-hand page and continue to the end of the right-hand page. You should be reading at a speed that allows you to savor and comprehend the material. Check the timer and see how long it took you to read these two pages. Write down that time.

- Now set the timer for 10 seconds less than it took you to read the first two pages. Try to read the next two pages before the timer sounds, retaining comprehension of the material.

- Now set the timer for 20 seconds less than it took you to read the first two pages. Try to read the next two pages before the timer sounds, retaining comprehension of the material.

- Finally, calculate how long it would have taken you to read four pages at your original speed (in other words, double your original time). Set the timer for 60 seconds less than that time. Try to read the next four pages before the timer sounds, retaining comprehension of the material.

- At the end of this exercise, you will have read 10 pages of your book, eight of them at an accelerated speed. You should feel somewhat energized and excited by this exercise. That is a sign that you're entering the connect brainset. Try to do this exercise once a day for a week or until you get used to the feeling of your thoughts speeding up. If you are using the token economy incentive, award yourself one connect token each time you complete this exercise.

Solution to the Nine-Dot Problem