9

9

Recognizing Useful Ideas: Accessing the Evaluate Brainset

Good judgment comes from experience, and a lot of that comes from bad judgment.

—ATTRIBUTED TO WILL ROGERS

Not All Ideas Are Good Ideas

YOU HAVE NOW SPENT some time in the absorb, envision, connect, and reason brainsets and you've generated a collection of original and novel ideas that you're really excited about. Now what? Generating novel ideas is essential to the creative process, but knowing how to hone down your collection of bright ideas to those that have a chance of being workable is also essential. Generating a number of novel ideas is not much use without the ability to tell a good idea from a bad one. So how do you accomplish this without doing injustice to those unique brainchildren you've just produced?

As it turns out we are equipped with incredible brain machinery to make judgments. In fact, a substantial part of our prefrontal cortex is devoted to this because making rapid but accurate decisions is so important to survival. It was essential, for example, for our Caveman #2 to be able to judge whether that moving shape behind the ginkgo tree was a potential meal (good) or a carnivorous predator (not so good). Likewise, it was important to judge whether those luscious berries growing on the vine were prehistoric blueberries (good) or poisonous pokeweed berries (ugh—not so good) or whether the approaching stranger was friend or foe.

To determine how good we are at making quick judgments based on first impressions, Nalini Ambady and Robert Rosenthal conducted a series of experiments at Harvard on our ability to make rapid assessments. They had undergraduates watch very short video clips of high school teachers lecturing in a classroom. The audio was removed so that the undergrads couldn't hear the teacher's voices, and the clips were randomly selected from long lectures so as not to focus on particular positive or negative behaviors of the teachers. Yet the undergrads were able to reliably judge which teachers received high ratings (based on performance evaluations by the school principal) and which received low ratings after watching a 10-second video clip. Ambady and Rosenthal then repeated the experiment using five-second and then two-second video clips. Untrained undergrads were still able to judge the good teachers from the bad teachers in just five seconds (although their judgment was less reliable at two seconds).1

Clearly humans would not be able to make such accurate and speedy judgments if being able to “size things up” were not an important aspect of all our endeavors. That is certainly the case with endeavors pertaining to creativity and innovation. Yet many people—and especially many of the highly creative people I work with—have a great deal of difficulty with this component of the creative process. One of the reasons for this difficulty is that their mental comfort zone is one of the idea-generating brainsets (especially absorb, envision, and connect), and they don't know how to get into the evaluate brainset.

Defining the Evaluate Brainset

The evaluate brainset is basically a brain state in which you are focused on judging an aspect of your environment.2 As part of the creative process, the aspect of the environment you'll be judging, of course, is your own work. This is always very tricky and has implications for self-esteem. Because self-esteem affects motivation, you run the risk of stalling your whole creative career if you are overly critical (the quintessential Type II error). On the other hand, if you're not critical enough, you may waste valuable time pursuing ideas or projects that have a low probability of panning out (the less emotionally devastating but still unpleasant Type I error).3

Three factors that are necessary for creativity and innovation define the evaluate brainset: active judgment, focused attention, and impersonality. On its surface (and indeed in its underlying brain activation pattern) the evaluate brainset is the mirror opposite of the absorb brainset, which is nonjudgmental and defocused. Let's look at each factor of the evaluate brainset separately.

Active Judgment

The goal of making judgments is to improve our ability to predict the future. It is a human tendency to categorize and judge things and experiences—to put them in neat pigeonholes so that we know what to expect from them if we encounter them again.4 Categorization is a form of judgment that improves our future speed of decision making based on past experience. If, for example, you stayed in a hotel in Costa Rica that featured lines of roaches streaming up the wall, you would categorize that place as “bad.” If, on the other hand, you stayed at a hotel that met your expectations, you would categorize it as “good.” Either way, your categorization effort will make your decision about where to stay on your next trip to that location easier and more efficient.

While improving the efficiency of decision making, however, judging decreases flexibility and closes doors. Judging decreases the possibility that a thing could be other than that which is dictated by the pigeonhole into which you have put it. Thus, by judging a novel as “bad,” you are dismissing the possibility that it might contain a great character or scene that you would like to revisit in the future. When you are in the absorb brainset, you loosen your need to judge things, and category boundaries become porous. In fact, you tend not to categorize at all. You are able to tolerate ambiguity about whether things are good or bad, right or wrong. You accept everything. This promotes intellectual curiosity; you won't automatically reject points of view because of some past categorical judgment. If your mental comfort zone is the absorb brainset, you are probably cringing right now at the thought of passing judgment on anything (let alone your own ideas)—you can just hear those doors of possibility creaking to a close!

There comes a time, however, when decisions have to be made and the next step has to be taken in order to progress. The evaluate brainset not only allows this, it enables it. In the evaluate brainset you are internally rewarded for making judgments. There is thus a pressure or drive to make judgments. You absorbers out there, get ready to put on your black judge's robes; you may find it very difficult to make categorical decisions, but no pain—no gain! Because making judgments and evaluations is difficult for many people who engage in creative work (simply because culling ideas seems totally opposite to generating ideas), I've divided the Active Judgments section into two parts: first, we'll look at how to force yourself to make judgments in general; then we'll progress to how to judge and evaluate your own creative ideas.

Making Judgments in General

In order to practice getting into the evaluate brainset, you can try some exercises that are based on work with hoarders. Hoarding is in many ways the opposite of the absorb brainset in that absorbers are so flexible in their thinking that they don't want to judge things for fear of limiting possibilities. Hoarders, on the other hand, are very rigid in their thinking; yet they also have trouble judging things—but their trouble is based on anxiety. Hoarders suffer from a type of anxiety disorder that makes it extremely painful for them to throw anything away, even meaningless candy wrappers, scraps of paper, or (yes, I'll say it) empty soup cans (remember all the uses for them you discovered in Chapter Seven?). They cannot judge these items as expendable because, for them, everything is imbued with emotional meaning. The attempt to throw away some of their trash can elicit extreme anxiety and even a panic attack. As a result, hoarders often live in homes that are piled to the ceiling with junk, creating a fire hazard and impossible living conditions.5

One way of dealing with this problem is to present a forced-choice scenario. In one component of cognitive-behavioral therapy, for instance, hoarders are presented with items that need to be removed from the living space and asked to categorize them into three groups: one group they will keep, one group they will sell or throw out, one group they will store to go through again later. In this way, hoarders make difficult judgments—under the watchful eye of a therapist—that ultimately allow them to remove over half of their stuff, improving their living conditions.6

Although you will not have a trained therapist to help you sort through your creative ideas, you can still take advantage of the forced-choice technique. (This is helpful not only to absorbers but also if your mental comfort zone is the connect brainset and you have a huge accumulation of ideas that are going nowhere.) You can sort your creative ideas into “keep,” “throw away,” and “store” categories to help you narrow down the ideas that are most worthy of your current development and attention. (For practice in categorizing and prioritizing, see Evaluation Exercises #1 and #2.)

Evaluating Your Own Ideas and Your Ongoing Work

In his 1996 book on creativity, psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi reports that at Nobel Prize–winning chemist Linus Pauling's 60th birthday party, a student asked him, “Dr. Pauling, how does one go about having good ideas?” Pauling replied, “You have a lot of ideas and throw away the bad ones.”7 In fact, the difference between being creatively productive and nonproductive may hinge on your ability to evaluate your ideas—to “throw away the bad ones.” To do that, of course, you have to have some idea of what constitutes a good and a bad idea.

One of the ways you do this is to learn as much as you can about the domain or area of creativity in which you're working. It's important to know the “rules” of the domain and how experts in that area evaluate creative work. (This of course takes time and experience in that domain: see the “10-Year Rule” and Exceptional Performance in Chapter Eleven).

You may be questioning this premise. After all, don't revolutionary and innovative ideas occur “outside the box”? Don't creative people break the established rules when they create? Yes—but they use “poetic license.” That is, they know the rules and choose to break them to solve a creative problem; that is more creative than not knowing the rules to begin with. Consider the poet who knows the rules that comprise a sonnet but chooses to break the rules for effect; that will generally produce a higher level of creative work than the novice who has no idea of what a sonnet is but writes a poem and calls it a sonnet anyway.

If you're totally unfamiliar with what constitutes good work in your field (whether that field is music, sales, or parenting, or any other area to which creative ideas can be applied), then you are not taking advantage of all the work that has been done by those who have gone before you. You also run the risk—excuse me, Caveman #2—of reinventing the wheel. You may put a great deal of effort into the production of something that's already been done.

Unfortunately, I see this all the time with novice psychology students in my classes. They come up with what they think is a revolutionary new idea and spend weeks developing their idea. When they finally show it to me, I have to inform them that if they'd just done a little more research they would have found their idea had already been fully explored. Sadly, the only way to know what constitutes a good idea in your field, what's been tried already and what hasn't, is to do your homework and know the background of the area in which you're doing creative work.

So, the first method of evaluating your creative idea is to determine how it would stack up next to other work in the same area of endeavor. But what if your creative idea isn't related to any established domain of work? That may certainly be the case if you're working in a relatively new genre or a new area of technology. (How, after all, could Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak have evaluated their idea for personal computers against an established domain of work?) Here are some general tips for evaluating your ideas.

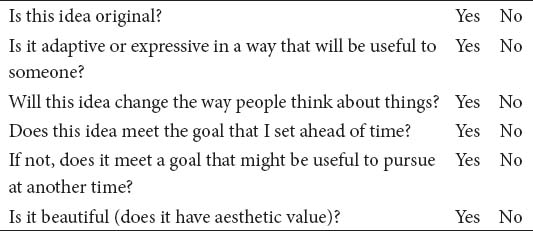

GENERAL TIPS FOR EVALUATING CREATIVE IDEAS

Deliberate judgment of your creative ideas requires comparing your idea to some criterion of acceptance. You can't judge whether an idea is good or bad unless you have some concept of what constitutes a good idea. If you had a specific goal in mind before you generated your creative solution, you can measure it against that goal. If you did not have a specific goal in mind (as is often the case when ideas “pop into your head” via the spontaneous pathway), you can measure them against the standards for all creative products:

If your answer is no to all of these questions, then you should reject your idea. If the answer is no to the first four questions but yes to one of the last two, decide whether this idea is worth dropping your current plan to pursue or whether you should record it and store it to pursue at a later date.

The criteria you will use to evaluate whether your creative ideas are worth pursuing are different from the criteria you will use to evaluate aspects of your ongoing work once you've decided to accept and build on a creative idea. In general, you should be more lenient in your acceptance of ideas and then become a somewhat harsher critic of aspects of your work in progress.

Here are some guidelines for evaluating your ongoing work that I've developed to help both novices and professionals constructively critique their creative projects:

- Get some distance. Put the work aside for a few days before you evaluate it. You cannot be objective when you are recently emerging from the throes of creative engagement. You will be too close to your work to give it a fair appraisal.

- Evaluate your work with respect. Give your work the same respect that you would give if someone you admire asked you to evaluate their work.

- Don't decide to throw out a work midway through the project. Discouragement may cause you to believe that the work will never amount to anything. However, remember that before you began the elaboration work, you evaluated this idea and gave it a thumbs-up; therefore, it must have some value. Tell yourself that you can always throw it out when it's finished if it doesn't meet muster.

- Look at individual parts of your work. Evaluate each part for its quality. Then look at how the part relates to the whole. Does each part contribute to the whole in a meaningful way? There will be many parts of which you're very proud and which are in fact very good, but if they don't relate to the whole work in a meaningful or satisfying way, then judge them accordingly. Remember that these parts can be preserved through photography or keyboard or recording to be part of a future project if they're that good (see Dealing with “Pets”).

- Look at the work from the point of view of the audience. Who will benefit from this work? If you can identify who will be the benefactors (your audience) then try to look at your work from their perspective. Does that change the way you evaluate the individual parts?

- Be flexible. Sometimes a work gets pulled by its own weight in a direction you weren't expecting. You may have a mental vision of what the final product is supposed to be, but that vision may be as much of a “pet” as the individual parts that don't fit in are. Be willing to alter your vision if the work is going in an interesting direction. You can always come back to your vision if the new path doesn't pan out. Novelists often claim that their story gets a life of its own and goes in a new (better) direction than the one they had originally envisioned. You can tentatively follow the new direction and retreat to the original idea if the new direction doesn't pan out.

- Decide whether to consult others. This is tricky. What are you going to do if the person you consult says the work is garbage but deep down inside you think it's good? Likewise, there's no benefit in consulting a “yes” person who will tell you your work is great no matter what they really think. And if someone tells you what they honestly think, it might destroy your momentum. If you're going to consult someone, it's best to ask them to give you concrete suggestions for improvement of your work rather than asking them to render judgment on a partially completed work-in-progress. Professional editors working with their authors know how make corrections and suggestions without destroying fragile egos; if your consultant will not be as delicate, you might consider waiting until the work is completed to show it to critics.

- Be hard on your work, not on yourself. Remember that it is the work you're judging. Put your best effort into the work and you'll be successful as a person regardless of how you ultimately judge this one piece of work.

One additional problem that often pops up during the evaluation of your work is how to handle an idea or an elaboration to which you are inappropriately attached. This could be the result of having a spontaneous idea (remember that spontaneous insights often arrive with a strong conviction of “rightness”) or it could be a paragraph, musical phrase, or other element of creative work that you worked really hard on and feel is perfectly executed. Here is some information on dealing with these “pet” creations.

DEALING WITH “PETS”

You have written a perfect mini-speech. It is witty and concise and written for the main character of your novel. You love this speech. The problem is it doesn't really fit into your plot. You spend days manipulating the plot just so that you can include this little speech. When you finally figure out how to fit it in, you've veered so far off course that you have to spend more days getting back to the original plotline of your novel.

Think about what you've done: you ruined the forest to save one tree. Everyone has their pet creations, something that they can't let go of despite all evidence that the “pet” is mucking up the works. It's a real problem.

However, modern technology has given us a way to deal with inappropriate “pets”: the answer is to put them on an outtakes reel. I recommend that my students have an outtakes file for every chapter, for every scene, for every painting, for every piece of music, and for every invention they create. When you realize that your pet has to go, simply copy and paste (or photograph and scan) your work into an outtakes file before deleting it from your work. Make sure that you have a method for preserving your unused pets. That way you can always reinstate them or go back to them for a later project, and parting with them is not such sweet sorrow.

(By the way, the concept of storing “pets” on an outtake reel has an analogy in our larger culture. It is an interesting phenomenon that at the cultural level, creativity has increased as a function of knowledge transmission. When all information had to be held in the head and passed on in the oral tradition, there wasn't much room for innovation and unproven “pets.” Only so much knowledge could be retained in the head to be passed down. However, when the written word developed, people could record both traditional knowledge and new ideas; in case the new ideas didn't pan out, the traditional ways were still preserved. This led to greater cultural creativity.8 Finally, with the advent of the Internet, even minor variations on new ideas (such as “pets”) can be retained, so we are able to branch further and further from tradition without fear of losing information valuable to our culture. Thus, culturally, we have access to even more information to combine and recombine in novel and creative ways.

Now that you have some ideas about how to force yourself to make decisions, how to evaluate your work, and how to deal with pet creations that are slowing down your progress, let's look at other aspects of the evaluate brainset that will help you make appropriate decisions about your work.

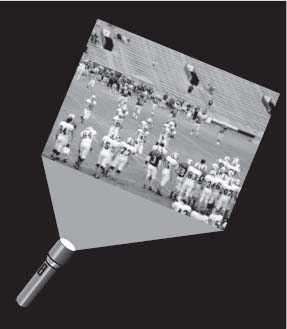

Focused Attention

When you're in the evaluate brainset, your attention is very focused, allowing you to hone in on small details rather than defocusing attention to let peripheral information into your cognitive workspace. Focused attention keeps you on task and concentrating on the pros and cons of your solution or project, which is what evaluation is all about. Focusing on a single item, aspect, or detail is quite difficult for people who are used to thinking in terms of imagination (envision brainset) or of connections between concepts (connect brainset). However, if your goal is to judge the worthiness of your idea or part of your idea, you need to stay focused on it and compare it to the standards you have set for appropriateness (more on that in a few minutes; for practice on maintaining focus, see Evaluate Exercises #3 and #4.)

Defocused attention is like a light with a broad but dim beam that allows many objects to be illuminated at once.

Focused attention is like a light with a narrow intense beam that can only illuminate a single object at a time.

Impersonality

Creative and innovative work takes courage. You are venturing into unknown territory when you create, and you are leaving yourself open to criticism, ridicule, failure, and all the other perils that can accompany breaking with established patterns of doing things. One of the perils that you are most open to is self-rebuke and self-criticism. It's extremely important to remain impersonal in the evaluate brainset; remaining impersonal entails keeping the volume turned down on the self-evaluative “Me” center in the brain. You are evaluating an idea or a piece of work—you are not evaluating yourself or your abilities.

You have to give yourself the freedom to fail. Failure is part of the idea-development process of creativity. Thomas Edison made literally thousands of mistakes as he sought to perfect the electric light-bulb. When asked about his failures, he is cited as responding, “I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work.”9 The Wright brothers, likewise, sustained many failures in their attempt to create controlled and sustained flight. You're going to be coming up with lots of new ideas. Remember what we said back in Chapter Seven; the number of good ideas and products you create is a function of the overall quantity of ideas and products. So the more you produce, the more “hits” you'll produce. Also the more you'll fail. Failure is expected and allowed! It only takes a small number of good ideas to make you successful, and then you'll forget about all those that didn't work. So do not self-flagellate when one of your ideas doesn't pan out.

Self-rebuke will stall your creative efforts. You need to monitor yourself, especially when you're in the judgmental evaluate mode to make sure (1) that you're not coming down on yourself for ideas that don't work, and (2) that you're not taking personally any criticism from others about your creative work.

If you start feeling low or discouraged about your idea or product, listen to the running commentary of thoughts in your mind—psychologists call this “self-talk.” Are you thinking negative things like “I'm no good at this,” “I might as well give up,” or “How can I be so stupid!”? If so, take a moment to consider what you're saying. Is there really any evidence for your negative thoughts? Because that's what the evaluate brainset is all about: making judgments based on evidence. So gather evidence for and against your negative self-talk, and then try to replace that self-talk with more positive and realistic statements, such as “Well, that's one idea that didn't work … on to the next one” or “That was a mistake—but if I don't make mistakes, I won't learn anything.”10 (For practice monitoring your negative self-talk and evaluating it, see Evaluate Exercise #5).

Finally, you need to know how to handle criticism from others about your creative ideas and work without taking it personally. This is quite difficult because even the best creative ideas are often met with skepticism, and it is painful to think that others don't have the same enthusiasm for your ideas that you have. Regardless of what others may say about embracing change, people are naturally cautious about accepting new ideas that threaten their old and comfortable ways of thinking or doing things. Learning to handle negative evaluation of your work in an impersonal but gracious manner is an important skill. Because criticism is inevitable when you're breaking new ground with creative ideas, it's a skill that will serve you well throughout your creative endeavors. Here are the rules I've developed for handling negative evaluation from others:

Rule #1

If someone is criticizing something you've done, that's a sign that you've done something to criticize! You've taken a risk and chosen something that's a challenge. Receiving criticism is therefore a badge of courage. Congratulate yourself! Doing something new and challenging, even if you're not yet good at it, is infinitely more rewarding than being praised for doing the same old thing well.

Rule #2

Consider criticism to be valuable feedback. If you don't take criticism as a personal attack, but rather look at it as an indicator of an area in which you need to improve or change course, you can use the feedback to self-correct. Think about a guided missile system. It has built-in monitors to detect when it's heading off course so that other parts of the guidance system can make the correction and get back on track. If you can put aside feeling personally attacked, you can use the feedback in criticism as part of your own self-correcting guidance system.

Rule #3

Do not defend yourself if criticized. When you receive criticism, it's very easy to feel as if you're being put on the defensive; this can make you feel that you need to take a stand and defend your work or your actions. Once you begin to defend your work, it is very unlikely that you will learn anything from the information others are trying to give you. Instead, you will entrench yourself in the position against the criticism. You learn nothing and your critic has wasted his or her breath in trying to give you some feedback. The worst-case scenario is that you'll actually launch a counterattack, and the person who was offering you feedback will become your adversary. Even if someone has delivered hostile or unjust criticism (perhaps out of jealousy or spitefulness), do not defend your position. Rather, thank the person for their feedback (see Rule #5) and ignore the criticism. Do not be pulled into battle by a hostile critic.

Rule #4

Rephrase the main points of the criticism. In most cases, spitefulness or hostility is not the motive for the criticism. Therefore, listen actively to what the person delivering the criticism has to say (that means you don't spend the time while they're talking to you planning what you're going to say back to them). When they're finished, paraphrase in a neutral (not angry or sarcastic) tone the points you think they were making. Example: “Okay, it sounds like you think my novel moves too slowly and that I need to develop the character of Edward more. You also think the description of the dinner party is too long. Is that right?” Now the person delivering the criticism can straighten out any misunderstandings, and he or she will feel that they've been heard. Note that this rule also applies if the person has delivered their criticism via e-mail, letter, or newspaper opinion column. This rule has two advantages for you: first, it takes the personal sting out of the criticism; it's much easier to hear the criticism when it's voiced in your own words. Second, it defuses the confrontational aspects of the criticism and makes the criticism part of a collaboration; it puts you and the critic on the same team working together to make your work better. When engaging in creative work, it's always better to have helpers rather than adversaries.

Rule #5

Thank the person criticizing your work for their feedback. Note that by thanking the person, you are not agreeing to incorporate their criticism. In private, you can analyze the criticism and decide whether to use it or disregard it. This step is also a good way to deal with blowhards and naysayers who are criticizing you for criticism's sake or to make themselves look important.

Rule #6

Determine the value of the criticism objectively. Once you've received criticism, look for the evidence for and against its validity. Try to do this objectively, and analyze each point of criticism separately. Even blowhards can offer valid points of criticism. After you've done an evidential analysis, you can decide whether to make changes based on the criticism. This rule also removes the subjective sting of the criticism and helps you deal with it objectively.

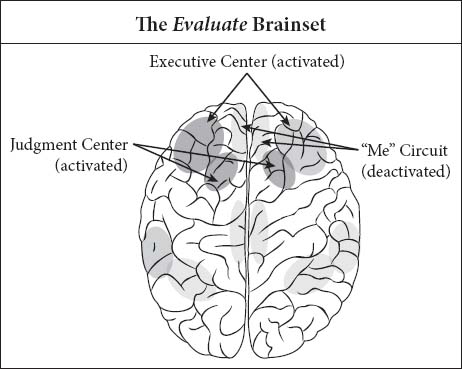

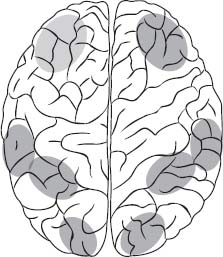

Neuroscience of the Evaluate Brainset

Exactly what does your brain look like when you access the evaluate brainset? Remember that the evaluate mode is characterized by active judgment, focused attention, and impersonality. The brain activation patterns of people when they're in the evaluate brainset reflect these characteristics. The evaluate brainset is similar to the reason brainset in activation pattern; this is because evaluating and making judgments are actually functions of the executive center that is so active during reasoned thought. Therefore, the areas of the prefrontal lobes that control decision making and inhibition are highly active. There is also preferential activation of the left hemisphere with relative deactivation in the right hemisphere when individuals are making categorization judgments. The orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex, areas that we named as part of the judgment center in Chapter Three, are active as well.11

Activation of the executive center and especially the left prefrontal cortex is an indication that this brainset is one of highly focused attention. We would expect high levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in the prefrontal cortex,12 although studies have not been conducted to confirm this. The new field of neuroeconomics combines research from both economics and neuroscience. It is beginning to explore how making judgments affects both the fear and reward systems in the brain.13 This new field will soon be able to tell us more about how specific neurotransmitters may facilitate or inhibit evaluation.

When to Access the Evaluate Brainset

Timing is important when you are accessing the evaluate brainset. Because it's the virtual opposite of the brainsets that you want to be using when you're coming up with creative ideas, this brainset will cut off further generation of ideas. However, it can be a useful tool for getting out of the connect brainset in which you just continue to spew ideas without ever acting on them.

I've worked with several artists and students who have this difficulty (including Richard, the film producer whom I mentioned in the preface). If the connect brainset is your mental comfort zone, you may have had this problem as well. I'm currently working with a writer who hasn't been able to get started on his next project because he's stuck in the idea-generating connect brainset. He keeps coming up with new ideas for the plot, and with every new idea he's off doing more research. While he's researching, he runs into something that gives him another new idea and he's off researching that. Just as when you're surfing the Net, one page leads you to another and another until you're totally off track from your initial search, stimuli in the world lead the person in the connect brainset on a chase far afield from his or her original intention. It feels almost blasphemous to put the brakes on when you're generating potentially good ideas (I mean, what if you never get back into that connect brainset?). However, you have to trust that you will be able to generate more ideas in the future. Note that too many ideas—as well as no ideas—can lead to creative block. And the best thing you can do now is to implement your best idea of today. If you have several ideas, begin evaluating now.

Besides getting you out of the idea-generating phase of the creative process, the evaluate brainset is, of course, where you want to be when you're deciding which idea or solution to implement. This happens during the evaluation stage of the creative process (macro-evaluation) and then off and on during the editing, elaboration, and implementation stages (micro-evaluation).

Criticism and evaluation are important parts of the creative process. However, the evaluate brainset is not conducive to generating new ideas or sustaining work on a complex project, so use it in small doses. If the evaluate brainset is your mental comfort zone, reward yourself with items from your Small Pleasures list (from Exercise #9 in Chapter Two) each time you successfully achieve the absorb, envision, or connect brainset. Being able to view the world from different perspectives will improve your evaluative skills even if your goal is to be a professional evaluator, such as an art, movie, or music critic.

Remember that the definition of creativity is something that's both original and useful or adaptive. You cannot determine whether your idea or solution meets those criteria unless you evaluate it.

One final reminder: judge your work and not yourself. Use criticism to your advantage and not as an indicator of your personal worthiness. If you are finding that you take criticism (both your own and other people's) too personally, you may actually be operating in the transform brainset rather than the evaluate brainset. When you're in the transform brainset, everything seems personal and (usually) deflating. To learn about how you can take this self-referential brain state and transform it into a creative advantage, read on!

Exercises: The Evaluate Brainset

Evaluate Exercise #1: Making Judgments: Forced Choice

Aim of exercise: To decrease the need to suspend judgment and improve evaluation skills. This exercise will take you between 10 and 15 minutes. You will need a writing utensil, two pieces of paper, and a timer or stopwatch. Try to do a version of this exercise once a week until making judgments about your own things is easy or you.

Procedure: On one sheet of paper, make a list of your 10 favorite books. Take some time with this. These should be books that are really meaningful to you. When you have your list, number the books (they don't have to be in any order, just assign each a number).

When you're ready, on the second piece of paper, write a row of numbers from one to ten, and beside each number write two words: “keep” and “throw.”

Now imagine that you're at sea on a small boat and you have to throw half of your books overboard to keep the boat from sinking. You will never see these books again.

Set your timer for two minutes. For each book on your list, decide whether you will keep it or throw it. Remember that you can only keep five. You must complete the list before the timer sounds.

If you are using the token economy incentive and you finish before the buzzer, give yourself two evaluate tokens. If you finished the list but did not complete it before the timer, give yourself one token.

This exercise is very effective in getting you to make rapid judgments about the value of your belongings; however, some people who have tried it find it somewhat traumatizing. One artist (whose mental comfort zone was the envision brainset) told me it reminded her of the movie Sophie's Choice and that she actually wept for a while over losing her beloved books. If you feel upset by the exercise (please don't laugh—envisioners with their strong imaginations can get caught up in the exercises), then mentally row the boat back out into the water with a grappling hook. Envision yourself retrieving the books, bringing them home and drying them by a warm, cozy fire, and restoring them to your bookshelf.

Repeat this exercise once a week with lists of other belongings that are important to you, such as: pairs of shoes, golf clubs, pieces of jewelry, or your CD collection. My clients have also used: their collection of T-shirts from bars across the globe, teddy bears, rare coins, and Mardi Gras beads. Envisioners, remember that you can go mentally retrieve your items from the water later, but try to sit with the discomfort of making serious judgments for a while first.

Evaluate Exercise #2: Making Judgments: Best and Worst

Aim of exercise: To decrease the need to suspend judgment and improve evaluation skills. This exercise will take you 10 minutes. You will need a writing utensil, a piece of paper, and a timer or stopwatch. Try to do this exercise once a week until making judgments about your own things is easy for you.

Procedure: On a sheet of paper, make a list of your six happiest moments from the past year. Take some time with this. These should be moments that are really meaningful to you. When you have your list, set the timer for two minutes.

Now rank the moments from the best to the worst with the best being number one.

If you are using the token economy incentive and you finish within the allotted time, give yourself one evaluate token.

Try to complete a version of this exercise every week until you feel comfortable rank-ordering things of personal value. You can use lists of other types of moments (most embarrassing, angriest, and so on) for the past year. This exercise will help you slip into the evaluate brainset more easily.

Evaluate Exercise #3: Focusing Attention: Watching the Clock

This exercise was adapted from Carol Vorderman's book Super Brain (see Vorderman, 2007). It has worked well for my creative artists, musicians, and writers who have trouble staying focused.

Aim of exercise: To improve your powers of concentration and focused attention. You will need an analog clock with a second hand. This exercise will take you between one and three minutes. Try to do this exercise once a day for progressively longer periods until you can remain focused for three minutes.

Procedure: Place the clock so it is in front of you. If it's on a wall, stand so that it's directly in front of you. Wait until the second hand reaches 12. Now focus all your concentration on the movement of the second hand. If a thought interferes with your concentration, stop the exercise and wait till the second hand reaches 12 again. Aim to focus on the second hand for 10 seconds without letting other thoughts intrude. Each time you do the exercise, gradually increase the time until you can focus for three minutes. If other thoughts intrude, try counting the seconds as you follow the hand. With practice, you should be able to totally focus on the second hand and nothing else.

If you are using the token economy incentive and you are able to focus for the time you stipulated for yourself today, give yourself one evaluate token.

Evaluate Exercise #4: Focusing Attention: Turn the Volume Down

This exercise was also adapted from Carol Vorderman's book Super Brain (2007). Thank you, Carol!

Aim of exercise: To improve your powers of concentration and focused attention. (This exercise may also improve your hearing.) You will need either a television or a radio plus a timer or stopwatch. This exercise will take you two minutes. Try to do this exercise once a day for two weeks.

Procedure: Turn the volume on the TV or radio down so that you can barely hear what's being said (tune to a talk station if you're using a radio). Now turn up the volume so that you can understand what's being said only if you really strain your ears and concentrate. Make a note of the volume level (many TVs and radios have a readout for volume level). Listen for two minutes, trying to decipher all that is said. Focus only on the voices you hear. If you can't understand anything, the volume is too low.

If you are using the token economy incentive, reward yourself with one evaluate token.

Try to do this exercise once a day for a couple of weeks, striving to turn the volume to a lower level while still being able to comprehend when you concentrate.

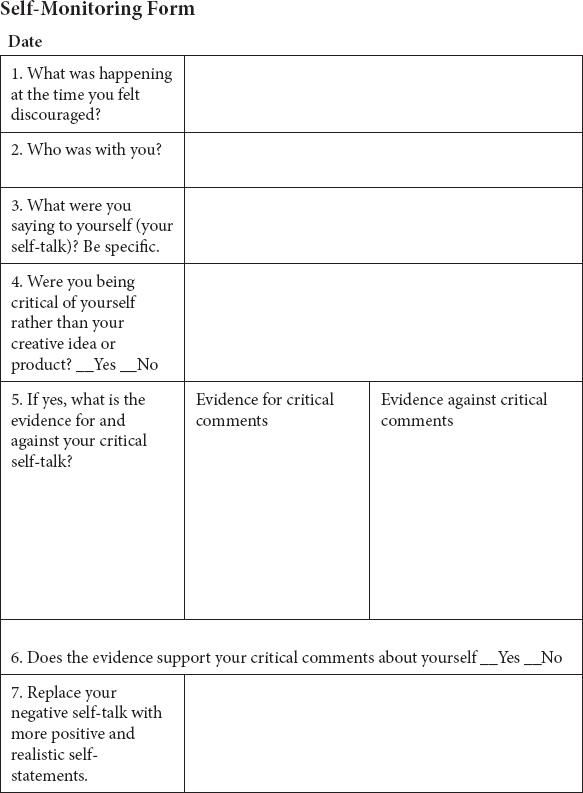

Evaluate Exercise #5: Self-Monitoring for Personal Criticism

Aim of exercise: To monitor your own thoughts for negative self-criticism that could hamper your creative efforts. You will need either a blank sheet of paper and a writing utensil, or you can make a copy of the following page. This exercise will take you around 10 minutes. Try to do this exercise whenever you feel discouraged about your creative problem.

Procedure: When you feel discouraged, answer the questions on the Self-Monitoring Form that follows.

Self-monitoring is a skill, and like all skills it needs to be practiced to be developed. However, once you get the hang of it, you'll find your outlook concerning yourself and your creative efforts will improve and you'll be more motivated to continue.

If you're using the token economy incentive, award yourself one evaluate token each time you fill out the Self-Monitoring Form to evaluate your self-criticism.

You can learn more about the technique of self-monitoring and download a copy of the Self-Monitoring Form used in this exercise on the Web site http://ShelleyCarson.com.