2

2

Your Mental Comfort Zone

SCENARIO:YOU'VE BEEN CHARGED with coming up with a theme for a fund-raising event for your community organization. Take a moment to determine which of the following strategies will be most helpful for you as you choose an appropriate yet compelling and novel theme:

- You scan newspapers and magazines for events to determine which themes have been used by other organizations.

- You think of the qualities and characteristics of your organization and consciously, through trial and error, focus in turn on how each of those qualities might be used in a theme.

- You absorb information about local events, you go to a party store and look around, you look through some historical documents about your organization; then you let all of that information congeal in your brain while you think about what you want for dinner.

- You send out a message asking for ideas from your colleagues, and then you judge each of the ideas that are submitted.

- You pick a common theme and then allow your mind to dance with the idea as you come up with ways to enhance, change, and embellish the common theme.

![]()

The truth is that any one of those strategies may lead you to pick an adequate theme for your fund-raiser. But if you could use all those strategies effectively . . . and use them in the right order . . . your chances of coming up with a great theme that will make your fundraiser a unique experience are multiplied exponentially!

You can use your creative brain to generate and execute creative ideas in any area of your life, whether it involves your business, social, personal, family, or artistic activities. Whether your task is to write a symphony, find ways to bring in new clients to your firm, or rearrange the living room furniture, you will be more successful if you take advantage of the best “state of brain” for the task.

In order to identify such brain states, I've combined findings from neuroimaging studies, brain injury cases, neuropsychological investigations, interviews with hundreds of creative achievers, extensive testing of additional hundreds of individuals in my research at Harvard, and information from the biographies of the world's most prominent creative luminaries. The result is the CREATES brainsets model, a set of seven brain activation states (or “brainsets”) that have relevance to the creative process. I've dubbed them “brainsets” because these brain activation patterns are the biological equivalents of “mindsets”; just as your mindset determines your mental attitude and interpretation of events, your brainset influences how you think, approach problems, and perceive the world.

The CREATES model for improving creativity and productivity is based on three findings that have substantial scientific support:

- First, creatively productive individuals are able to access specific brain states that others may find more difficult or more uncomfortable to access (note that this ability to access brain states may be due to genetic or environmental factors or a combination of both).

- Second, creatively productive individuals are able to switch among different brainsets depending upon the task at hand.

- Third, it is possible to train yourself to access these creative brain-sets and to switch flexibly among them, even if this does not come naturally to you at first.1

As you read about the brainsets in the CREATES model, you'll notice that there is a certain amount of overlap in both brain activation and brain function among them; they are not wholly discrete states. This is because most parts of the brain perform several different functions depending upon which other parts of the brain are simultaneously activated or deactivated. The interactions and interconnections among brain structures are enormously complex (as we would expect in an organ that has conceived such diverse concepts as the CERN particle accelerator and the American Idol reality show). We are only beginning to fully understand this complexity.

I don't want to mislead you into thinking that the CREATES model—or the neuroscience research presented in this book—is the final answer in the description of the creative brain. The CREATES brainsets are hypothetical constructs based on our current knowledge of human psychology and how the brain works. As our knowledge of the wonderful human brain expands, so will our understanding of the CREATES model. This current set of brain activation patterns will no doubt be amended, and additional brainsets that can benefit us in our creative endeavors will be described. We will also find more efficient methods of accessing these brainsets. With these caveats in mind, let's take a brief look at the brainsets that comprise the CREATES model:

Connect

Reason

Envision

Absorb

Transform

Evaluate

Stream

The Connect Brainset

When you access the connect brainset, you enter a defocused state of attention that allows you to see the connections between objects or concepts that are quite disparate in nature. You are able to generate multiple solutions to a given problem rather than focusing on a single solution. The ability to generate multiple solutions is combined with an upswing in positive emotion that also provides incentive and motivation to keep you interested in your creative project. I've based the connect brainset on research that examines a type of cognition called divergent thinking, as well as on research into how we make mental associations, and a condition known as synaesthesia. You'll learn about divergent thinking, synaesthesia, and the connect brainset in Chapter Seven.

The Reason Brainset

When you access the reason brainset, you consciously manipulate information in your working memory to solve a problem. This is the state of purposeful planning that comprises much of our daily consciously directed mental activity. When you say that you're “thinking” about something, you are generally referring to this brainset. The reason brainset is derived from neuroimaging research that has examined consciously directed aspects of cognition, including establishing goals, abstract reasoning, and decision making. You'll learn about these aspects of cognition, which are sometimes referred to as “executive functions,” and the reason brainset in Chapter Eight.

The Envision Brainset

When you access the envision brainset, you think visually rather than verbally. You are able to see and manipulate objects in your mind's eye. You see patterns emerge. In this brainset you tend to think metaphorically as you “see” the similarities between disparate concepts. This is the brainset of imagination. I've based the envision brainset primarily on research that examines mental imagery and imagination. You'll learn about mental imagery, visualization, imagination, and the envision brainset in Chapter Six.

The Absorb Brainset

When you access the absorb brainset, you open your mind to new experiences and ideas. You uncritically view your world and take in knowledge. Everything fascinates you and attracts your attention. This state is helpful during the knowledge-gathering and incubation stages of the creative process (you'll learn more about the creative process in Chapter Four). The absorb brainset is based primarily on research that examines mindfulness, the personality trait of openness to experience, and investigations into how we respond to unusual or novel events. You'll learn about openness, novelty, and the absorb brainset in Chapter Five.

The Transform Brainset

When you access the transform brainset, you find yourself in a self-conscious and dissatisfied—or even distressed—state of mind. You can use this state to transform negative energy into works of art and great performances. In this state you are painfully vulnerable; but you are also motivated to express (in creative form) the pain, the anxieties, and the hopes that we all share as part of the human experience. I've based the transform brainset on research that examines the relationship between mood and creativity. Historians, biographers, and scientists have long noted an association between creativity and certain types of mental illness, such as depression. Does such an association exist? You'll learn about this relationship and the transform brainset in Chapter Ten.

The Evaluate Brainset

When you access the evaluate brainset, you consciously judge the value of ideas, concepts, products, behaviors, or individuals. This is the “critical eye” of mental activity. This brainset allows you to evaluate your creative ideas and products to ensure that they meet your criteria for usefulness and appropriateness. The construction of the evaluate brainset stems from research conducted on how we make judgments and eliminate options. The neural architecture that allows us to make rapid and accurate judgments appears to be dependent not only on turning up the activation in certain parts of the brain, but also on turning down the activation in other parts. You'll learn about judgments and the evaluate brainset in Chapter Nine.

The Stream Brainset

When you access the stream brainset, your thoughts and actions begin to flow in a steady harmonious sequence, almost as if they were orchestrated by outside forces. The stream brainset is associated with the production of creative material, such as jazz improvisation, narrative writing (as in novels or short stories), sculpting or painting, and the step-by-step revelation of scientific discovery. This state is important in the elaboration stage of the creative process. The stream brainset comes from research conducted on improvisation in music, theater, and speech, and on a mental state described by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi as flow.2 This state has also been called being “in the zone” or “in the groove.” You'll learn about improvisation, flow, and the stream brainset in Chapter Eleven.

You will likely find that some brainsets feel more comfortable to you than others. These brainsets comprise your mental comfort zone, and you need to identify them before you can expand your creative horizons. You can get an idea of your personal mental comfort zone by completing the questions and exercises on the following pages. This is not a scientifically validated test, and there are no right or wrong answers; rather, the questions and exercises are indicators of your personal preference.

Which Brainset Do You Prefer?

Cluster One Questions are multiple choice. You can complete them in only a few minutes to get an idea of your preferred brainset.

Cluster Two Questions are “hands-on” exercises that will take longer but will give you a richer understanding of your mental comfort zone. Again, the test is not scientifically validated; however, the individual questions and exercises have been based on findings from the areas of research that form the basis of each of the seven brainsets. The students and creative groups that I work with have found this assessment to be informative as well as fun. You will find the material in Part Two of this book more personally relevant if you have an idea of your own mental comfort zone. You can choose to do Cluster One now and save Cluster Two for later or you can complete both at the same time.

Cluster One Questions

Please circle the answer that applies to you most of the time. Remember that there are no wrong answers.

- When you read a magazine article, do you tend to skim the article looking for the main points or do you tend to read the article from the beginning word for word?

a. skim b. word for word - When someone proposes a new project, are you able to immediately see what might go wrong?

a. yes b. no - Do you tend to prefer to multitask or do you tend to work on one project at a time?

a. multitask b. one project at a time - Do you have a good sense of time or do you find that you often lose track of time?

a. good sense of time b. often lose track of time - Is it easy for you to think up new ideas?

a. yes b. no - Are you particularly good at spelling?

a. yes b. no - Do you find it hard to get hooked into the story of a movie or novel?

a. yes b. no - Do you often have vivid dreams?

a. yes b. no - Are you good at solving crossword puzzles?

a. yes b. no - Do you consider the following statement to be true or false: “Everything is connected to everything else.”

a. true b. false - When you go on vacation, do you prefer to have a set itinerary or do you prefer to have a freeform vacation?

a. set itinerary b. freeform - Do you prefer to eat dinner at the same time each night or do you prefer to eat whenever you get hungry?

a. set time b. when I get hungry - When deciding how to get from point A to point B, do you prefer to have written or verbal instructions, or do you prefer to look at a map?

a. written instructions b. map - Do you believe you may be psychic?

a. yes b. no - Do you tend to think more in pictures or in words?

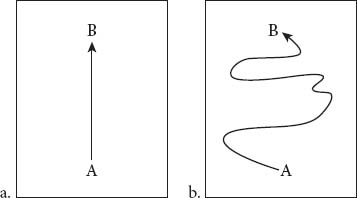

a. pictures b. words - Point A is your starting point and Point B is your destination. Which of the two paths below reflects your preferred journey?

a. path a b. path b - Do you think you would make a good movie critic?

a. yes b. no - How do you typically respond if someone criticizes one of your ideas?

- try to get something constructive out of the criticism that can help you

- become irritated with the critic

- feel humiliated and shamed

- Do you tend to spend a lot of time daydreaming?

a. yes b. no - When you walk into a room, can you quickly notice if something is out of place?

a. yes b. no - Do you enjoy cleaning out your car, or do you find it to be a necessary chore?

a. enjoy b. chore - Does it feel like others just don't move fast enough for you?

a. yes b. no

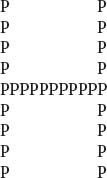

- When you looked at the above diagram, which letter did you notice first?

a. P b. H - You've consented to host a fundraiser for a local charity at your home. Which of the tasks below describes the part you would like to play in this event?

- I have a vision for the theme of this event, and I'd like to tell others my vision and let them handle the details.

- I'd like to be directly involved in details such as planning the menu, the decorations, the entertainment, and the publicity.

- I'd like to be involved in as few details as possible. Just tell me when to show up for the party.

- I only consented to be the host because I felt guilty about not doing enough for my community.

- Do you have days where you just don't want to get out of bed?

a. yes b. not really - Do you get excited to start a new project but have trouble finishing it?

a. yes b. no - Do you have trouble filtering out distracting noises?

a. yes b. no - Would others describe you as a “go-getter”?

a. yes b. no - Do you often have periods where ideas chase each other in your head so fast you can hardly keep track of them?

a. occasionally b. often c. never - Do you often go on spending sprees?

a. occasionally b. often c. never - Which of the following best describes how you would like to spend an evening with a friend?

- go to a movie and dinner

- go someplace quiet to talk about your problems

- Do you think other people would consider you to be upbeat or sort of a drag?

a. upbeat b. a drag

The scoresheet for the Cluster One Questions is located in Appendix One. You can either fill out the scoresheet now or complete the Cluster Two Exercises beginning on the next page.

Cluster Two Exercises

The Cluster One Questions make up a “self-report” assessment. That is, the responses are based on the responder's opinion of the appropriate answer. Even though people try to be honest, their answers to self-report questions can still be biased. For instance, they may unconsciously select the answer they think is most socially desirable. Or, if they don't like the assessment, they may unconsciously try to sabotage the results.

Researchers, therefore, try to give additional assessments that measure behavior rather than personal opinion when possible. That's why the Cluster Two Questions are included (besides, they're fun!). Though the Cluster Two exercises as a whole have not been empirically validated, each of the exercises has been used separately to evaluate some aspect of psychological or brain functioning related to the seven brainsets. The best evaluation of your mental comfort zone will come from combining the results of both the Cluster One Questions and the Cluster Two Exercises.

For this part of the assessment you will need a stopwatch or timer, several pieces of blank paper, a pen or pencil, a ruler with metric measurements, and about 25 minutes of uninterrupted time. Before you begin, cut a blank piece of paper to the size of this page. Do not look at the exercises until you're ready to begin.

Read these directions and then set the timer for three minutes. Find and count all the words in the passage on the next page that have both the letter s and the letter t in the same word. The letters do not need to be next to each other. When your timer goes off, stop reading and record the number of words you found that contained both s and t.

Much of the work your brain completes is done below the level of your conscious awareness. You don't even know it's happening . . . and it's amazing stuff. Neuroscientists refer to this unconscious brain work as implicit processing. Since much of the process of creativity is implicit, it's important that you know and trust what's going on in there.

Let's take a very simplified look at implicit processing. For example, what processes occur when you recognize a familiar face? First, you take in information through your eyes. Now your eyes don't “recognize” a face—they just pass on information coming in from the environment about color, shape, and movement. Color, shape, and movement are all processed by different parts of the vision system located in the back of the brain (in the occipital lobes). Once each of these streams of information has been processed, they are assembled in an association area of the occipital lobes. If the assembled picture looks like a face, this information is then delivered to a brain structure deep in the temporal lobe called the fusiform gyrus, where it is checked against patterns of familiar faces. Simultaneously, the information is sent to other parts of the limbic system (located primarily in those subcortical structures deep inside the temporal lobe) that determine whether the face is friend or foe. In other words, should you approach or run from this face? And still other parts of the brain associate the face with additional visual and sound information (such as posture, the way the person walks, the sound of her voice), as well as with other information known about this person. Only then does the lightbulb of recognition illuminate, and you realize Hey, that person in the produce aisle is my old high school teacher!

- Number of words you found that contained both s and t:

_____________

- Did you finish the passage in the allotted time?

a. yes b. no - Did you find that you read the content of the passage, or were you able to concentrate on finding the letters s and t?

a. read the content b. concentrated on the letters - Without looking back, what part of the brain recognizes familiar faces?

a. amygdala b. hippocampus c. fusiform gyrus

EXERCISE #2 PART 1

Set your timer for thirty seconds. Now, look carefully at the dot on the opposite page until the timer goes off. Then turn the page and proceed to Exercise #3.

Read these directions and then set the timer for three minutes.

Your friend Ron sits at the desk in the cubicle next to you. Ron really likes to talk to you and often bothers you while you're phoning clients, and many times you don't finish your work because he is bothering you.

Think of as many ways as you can to solve this problem and write them on a blank sheet of paper. Stop writing when the timer goes off.

Time how long it takes you to complete the following exercise in your head (don't write anything on paper while you're trying to solve it). There is no time limit.

Find a common English three-letter word, knowing that

- L O G has no common letter with it.

- T O G has one common letter, not at the correct place.

- S I T has one common letter, at the correct place.

- GOB has one common letter, not at the correct place.

- A I L has one common letter, not at the correct place.3

- The three-letter word is ___________

- How long did the exercise take? ____________

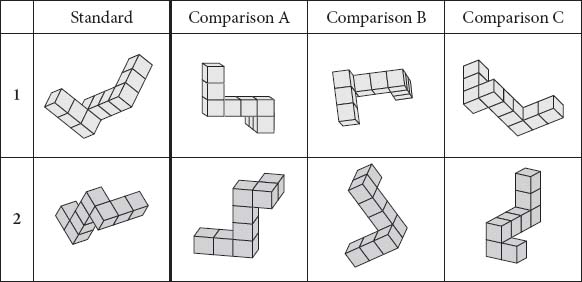

Time how long it takes you to find the solution to the mental rotation puzzles below.4 For each problem, decide which of the comparison shapes on the right is identical to the standard shape on the left. There is no time limit.

How long did it take to solve both problems? _______________

Set the timer for five minutes. On a separate sheet of paper, finish the following story. Stop writing when the timer goes off.

It was a dark and stormy night. I was driving west on I-90 when the lighting on my dashboard began to go dim and the car began to lose speed. I pulled over onto the shoulder just as the car died completely. I flicked on the hazard lights and pulled out my cell phone. Why hadn't I remembered to charge the phone battery before I left? I crossed my fingers that I had enough juice to make one call. That's when I realized . . .

On a separate sheet of paper, describe what you see in the following picture.5 Describe your first impression. Then look at it again and see if you see something different. Describe what you see.

Set the timer for three minutes. Find and count the proofreading errors in this passage. Stop when the timer goes off.

If you're tempted to skip the mini neuro-anatomy lesson in the next chapter, don't! Late, when you're practicing the brainsets, you'll need to know which parts of the brain your amping up or down. By visualizig your brain, you will be better able to enter each each brainset.

A number of artists and writers dosn't want to know what's going on in their brains for fear of shattering the mystical process called inspiration or illumination. Inspiration is the magical moment when an idea springs seemingly fully-formed from nowhere into conscious awareness. While some researcher have indeed tried to remove the mystique from the creative process, that is definitely not the purpose of theses book. In fact, the more you learn about how your brain takes perceptual infrmation from the environment and transform it into ideas that lead to skyscrapers and symphonies, the more you'll stand in awe of the process of creative inspiration. Just as knowing that men landed on the moon and brought back moon rocks doesn't shatter the mystique of the moon, the fact that we can now see inside the living human brain does not shatter the mystique of that marvelous courteous.

- How many errors did you find? ________

- Were you distracted by the content of the passage or were you able to concentrate on the errors?

- distracted by content

- able to concentrate on errors

Set the timer for five minutes. On a separate sheet of paper, write down all the small things you can think of that give you pleasure. The list should include activities that can be completed in your own home and without the participation of other people.

Some examples:

- Listening to a favorite musical piece (name the music)

- Taking a hot shower

- Drinking a cold glass of water

- Drinking a favorite hot beverage (such as coffee or herbal tea)

- Looking at a favorite photograph

- Reading a favorite poem

- Remembering a happy event

Make your list specific, so that you describe the memory or the favorite music. Keep writing until the timer goes off.

Note: you will be using this Small Pleasures list in later chapters, so you might want to rewrite or type it on a clean sheet of paper.

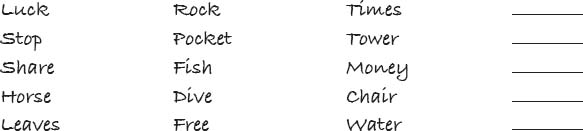

Set the timer for five minutes. In this exercise you are presented with three words and asked to find a fourth word that is related to all three.6 Here's an example:

![]()

The answer in this case is “house”: House paint, doll house, and house cat.

Try to answer all five of the following word combinations before the timer sounds.

EXERCISE #2 PART 2

Take the piece of paper you cut that is the size of this page and, without looking back, draw a dot on the page in the exact location that you remember seeing the dot in the first part of Exercise 2.

Now go back to that page and place your paper over the page. Place your ruler so that it is parallel to the binding of the book and measure how far off your dot is vertically from the original dot. Next place your ruler perpendicular to the binding and measure how far off your dot is horizontally from the original dot. Add the vertical difference and horizontal difference together.

- The difference is less than three centimeters

- The difference is greater than or equal to three centimeters

You can score your exercises and interpret the results using the guidelines in Appendix One.

Now that you know which brainset you prefer, it's time to think about leaving your mental comfort zone. Just as an athlete works on the mechanics of his or her sport that don't come naturally in order to improve or excel, you need to broaden the mechanics of your mental comfort zone to improve your creative thinking skills. This means that you may have to venture into mental territory that feels strange or unfamiliar to your creative brain. But don't worry, I think you'll find that rewards are worth the effort!

Before you start training your brain, however, you need to know your way around it. In the next chapter, you'll begin your journey into the vast fertile territory of your own creative brain. That journey will prepare you to process and appreciate more of the stimuli you encounter every day, to organize it, and to use it creatively.