How is it that in 2016 the world of architecture is still debating the gender agenda? How can it be that RIBA, representing a profession that is so concerned with respecting the needs of society, still requires a dedicated group to deal with matters of diversity? The answer is in the alarming fact that a mere 22% of all registered UK architects1 and 17% of UK Chartered RIBA members are women.2

In seeking to examine the question of discrimination in the UK, this book raises issues that spread beyond these shores. In the UK, anyone calling themselves an architect is required by law to register with the Architects Registration Board (ARB), whereas joining RIBA and having the right to append those four important letters to one’s name is an optional extra. Not all people who create stunning architecture are registered architects; not all people who are registered architects, producing amazing buildings, are members of RIBA. This detail makes collecting and handling statistics difficult and unreliable. It is curious to both authors that the percentages of women and ethnic minorities who are members of RIBA are lower than those who are ARB members. RIBA is the only body which takes an active pastoral role in looking after architects, through the sub-group Architects for Change (AfC). The group was set up in 2000 to address equality, diversity and inclusivity issues across education and practice. AfC was established as an umbrella organisation to gather together minority groups including Women in Architecture (WIA), the Society of Black Architects (SOBA) and the student group (then known as Archaos, which was disbanded in 2014 and has now been replaced by the Architecture Students Network). AfC’s remit was to ‘challenge and support RIBA in developing policies and action that promote improved equality of opportunity and diversity in the architectural profession’.3 The wisdom and challenges of creating an elite group is debated in this book, but our shared view is that isolated, side-lined individuals can only be given a voice by having the power of the group behind them.

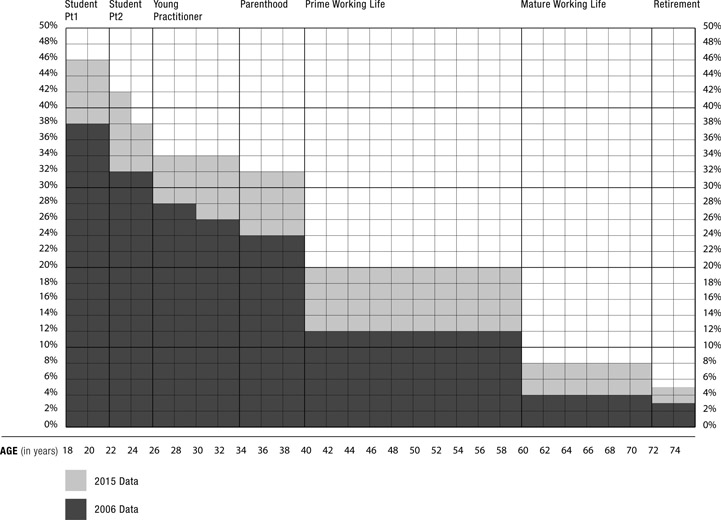

The latest (2015) statistics collected by RIBA from UK schools of architecture still indicate that women drop out of architectural education at a faster rate than men. Of those entering and passing Part 1 (undergraduate), 46% are women; of those entering Part 2 (postgraduate), 43% are women, dropping to 38% who actually pass. The same percentage pass Part 3 (the entry-to-profession exam). This implies that although Part 2 is a crunch time for women during education, if you manage to survive that stage you are likely to qualify as an architect.

However, closer examination of these statistics is needed in the light of the fact that, as of 2015, more people entered the profession with equivalent EU qualifications than by taking the RIBA route of Parts 1, 2 and 3. Time will tell whether this will have any impact on quality of design and the competence of the profession, but we can be certain that it will have a dramatic effect on education.

The decline of women architects

Ten years ago, WIA prepared a graph intended to illustrate the tragic decline in the percentage of women architects during key career stages: starting from the point of entering architecture school (in 2006, 35% of undergraduates were female) and extending to the point of retirement (in the same year, only 4% had made it this far). It is clear that the issues facing women architects at different times in their career are not the same; they could not be lumped together as the ‘woman issue’. Today’s comparison with career stage information captured by RIBA4 reveals that the percentage of females at all career stages has increased significantly. Those completing Part 2 have increased from 29% to the 38% noted above; young practitioners (ages 26 to 33 years) have increased from 27% to 35%; those in the ‘parenthood’ years when maternity and family issues are most pressing (ages 34 to 40) have increased from 23% to 32%; those in their ‘prime working life’ (ages 40 to 60) have increased from 12% to 20%; and those in their ‘mature working life’ (60+) have doubled from 4% to 8%.

We believe this trend is pleasing and sustainable. It shows that the rate of attrition is reducing and this in turn helps encourage more women to enter the profession. However, there are still evidently significant issues within both the profession and society at large that must be overcome before we reach the targets set by Building Design’s 50/50 Campaign initiated in 2005, when a mere 14% of registered architects were women.5 Assuming that the same proportion of this generation of women architects have babies,6 then the increase in the numbers returning to the profession may well be the effect of more men taking on the role of primary carer. While the introduction of shared parental leave7 has enabled childcare to move from being an issue of gender to one of equality, the problem facing women is still one of retention and progression, not recruitment.

With the ratio of women architects increasing, it is interesting to examine the numbers of women involved in governance of RIBA. The fact that this statistic is available shows how far RIBA has come in addressing the gender agenda. The most prominent statistic, that there had been no female president for 175 years, is extraordinary. But what is even more extraordinary is that following the inauguration of Ruth Reed as the first female president in 2009, there have been a further two women and one man. At present, 16 of the 60 RIBA council members are female (just over 25%). This same percentage is reflected at board level.

It is important to understand the attitude of architects to the Institute. There is a general sentiment among non-members (and, dare we say it, some members), particularly women, that RIBA is a white middle class boys’ club that has no interest or relevance for them. Whilst the statistics support this belief, meaningful change will only happen if women and people from black and ethnic minority backgrounds put themselves forward and become visible and influential. They must be present at all levels of committees and boards within the institute as well as on all juries, conference panels, think tanks, etc. We are not talking about the token woman who so often appears once the organisers have considered the monochrome panel that they have put together.

The authors here represent the first RIBA diversity champion (Jane Duncan), who shaped the role with a particular emphasis on developing career progression for women, and the current RIBA ambassador for equality, diversity and inclusion (Virginia Newman), who has an equally free-ranging role to tackle these issues. The fact that a former diversity champion is now RIBA President is fortuitous for the success of any initiative to address the retention of women.

We believe that there is a coming together of significant events that will enable change to happen. The legal framework is driving change with such moves as shared parental leave, equal pay and the composition of teams for public funded projects. High profile, successful women architects are becoming more visible as amazing role models to inspire the younger generations. There is a generation of men in positions of influence who have high-powered partners or daughters whom they do not wish to be treated as second-class citizens. And RIBA is currently led by someone who is committed to tackling these issues. Women architects, we need to stand up and be counted and take advantage of this moment.