An associate director in a London architectural practice reports that every Friday evening he would walk around the office commanding young employees to leave, switching off their desk lights to underline his instructions. His young workers had internalised the profession’s ethos of a ‘commitment to architecture’ enacted through long work hours.1 Young architects are highly conscious of their own and their colleagues’ timetables. An older architect has described this culture as ‘competitive overstaying’, as employees contend with each other to demonstrate loyalty and devotion to work.

Heightened awareness of work patterns is fostered by commonplace spatial practices. Contemporary open-plan layouts in architectural offices organise space through banks of desks that are easily surveyed. The flat, open floor plan is derived from 1950s concepts of the office landscape and Frank Lloyd Wright’s translation of the factory floor model into white-collar desk layouts at his 1906 Larkin Building.2 However the survey-able desk has an even longer history, arguably originating in the 19th century practice of apprenticed pupils paying an established architect for drawing instruction. The surviving Upper Drawing Office (designed 1821, rebuilt 1824) at the John Soane Museum demonstrates this system. Soane’s room is dominated by two parallel wooden, drafting tables with chairs for students placed on the inside of the tables; training students’ eyes towards the fragments of classical architecture adorning the drawing room walls. The most senior draughtsman probably sat between the tables and cast a rigorous eye on his pupils.3 In today’s open-plan office, tacit mechanisms of invigilation and internal self-surveillance exist alongside professed ideals of teamwork and collaboration.

Beliefs and work practices are entwined in architecture’s ‘long hours’ culture, a pattern that begins in architecture schools and continues beyond graduation. In recent years advocates of gender equity in architecture – including the advocacy organisation to which I belong, Parlour – have challenged the long hours system, arguing that this culture provides a strong barrier for mid-career women, retards the retention of female architects, and hinders women’s progression to senior levels. This chapter documents the phenomenon of overwork in architecture and explains how this system disadvantages women, caregivers, and older workers, and presents models of alternative flexible work organisation.4

Overwork as Sacrifice

From the early 1980s into the 2000s, overwork – the practice of working 50 hours or more a week – was a rising trend in managerial and professional occupations.5 Amongst professionals, working full-time is now typically understood to be a 40-plus hours week.6 Data gathered from the 2011 Australian census confirms the prevalence of long work hours in architecture. Between 30% and 35% of male architects, depending on their age, work 49 hours and above per week, and 50% of Australian architects work 40-plus hours a week.7 Only half of the women in the census reported working a 49-plus hour week. Architecture’s rates of overwork are several percentage points higher than other Australian professions.8 From the 1980s, economic contraction arguably placed higher expectations for productivity on salaried workers.

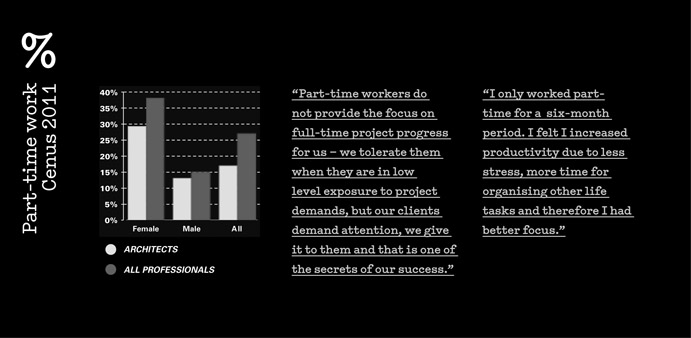

Data from the 2011 Australian census on hours worked

Architectural training and practice has its own particular myths and beliefs, both conscious and unconscious, of the ‘ideal’ architect; these underpin architectural culture. These myths can reinforce, normalise and even idealise patterns of overwork. One anonymous contributor, writing on the blog Architecture: What I wish I’d known, argues that these ideals are embedded in a mythic narrative structure of the architect’s ‘heroic journey of self-sacrifice’.9 This trope configures a hero-architect completely dedicated to his art and prepared to make sacrifices to bring his projects to fruition. (The male pronoun is intentional here.) As a number of academic studies have demonstrated, this archetype is implanted in the practices of architectural education centred around the design studio, intense design charrettes, trial-by jury and all-nighters.10 The blogger asks, ‘What is to keep this future practitioner from believing that good work only comes from a high degree of self-sacrifice?’11 The symbolic values attached to work are part of the organisational culture of workplaces. Cultural beliefs must be tackled if we are to achieve change.

The schema of ‘work devotion’ found in the architecture industry parallels a broader trend amongst the managerial and professional classes. Across the professions, the work contract has been transformed into a ‘moral bond’.12 Subjective values associated with longer work hours include organisational loyalty, status, commitment and productivity.13 While some see work devotion as coercive and seductive, many Australian architectural respondents to large-scale surveys conducted by Parlour in 2012 reported a strong belief in architectural work as community service.14 The devotional norm is not always a problem but it can be when this value system determines time standards and produces inflexible attitudes.15

The value system attached to long hours is exposed by the bias levied against workers who cannot conform to practices of standard or overwork; they fail to ‘meet’ the symbolic attributes of commitment and productivity attached to lengthy workdays. Women disproportionately bear this burden, but research suggests that increasingly men feel this approbation. A male architect reported in the 2012 Parlour survey, ‘The biggest impediment to an architectural career for both men and women is the need to leave a large city practice on time to spend time with family or care for elderly parents. While not part-time this is not seen as committed enough and architects are not encouraged to negotiate this issue’. Another male architect surveyed for Parlour noted, ‘I work four days per week. It is perceived badly, as a lack of commitment, yet I still meet all my deadlines’. In both quotations we hear how architects have encountered the invisible workplace cultural system that equates commitment to work with full-time hours.

Women with children face another barrier, and are perceived to have divided loyalties. One woman respondent to the Parlour survey wrote, ‘As soon as I started working part-time my employers treated me differently and assumed I was less committed. I was overlooked for promotion twice when I was on maternity leave and not even informed that structural changes were being considered. Hence I now work for myself’.16

Flexibility Stigma

The negative interpretation of non-standard patterns of work is not confined to architecture. Workplace forms of flexibility have been well known for decades – part-time schedules, flexitime, compressed workweeks and job shares – but the scarcity of these schemes has intrigued researchers. Investigations strive to understand why flexibility schemes are so infrequently exercised.17 Widespread ‘flexibility bias’ has been discovered in the professions and managerial occupations. Stigmatisation can result from requests for flexibility, or accompany employees who practise non-standard work patterns. If overwork is read as a signal of productivity and commitment, flexibility can be perceived as a conflict with an organisation or profession’s norms. Flexible or part-time workers can be catalogued as ‘time deviants’ whose request for a variable schedule is a violation of time norms.18

Rates of flexibility censure vary but are reported as higher in male dominated professions, which would include architecture.19 An individual’s minority status also determines whether they are more likely to ‘be viewed stereotypically’ and rebuked, but so are those working in ‘more hierarchical, bureaucratic organisations’.20 In female dominated professions flexibility does not engender hostility and work schedules are more fluid and accommodating.21 Individual access to variable work timetables is configured by attributes of class and race: men who occupy higher status jobs have more control over their work plans.22

Theoretically ‘work devotion’ is gender neutral, but the long work day and long working week relies on a social foundation of gender norms that disadvantages women.23 The ideal worker stereotype is still predicated on a male model of the salaried man ‘unencumbered by caregiving responsibilities’.24 Many women who are carers – and some male parents – face gendered social models that place care and work in conflict. Now younger men have to increasingly negotiate the schism between the older breadwinner model, and the ‘new, involved fathering ideal’: the father who actively participates in the details of day-to-day childcare.25 As the earlier quotations from male architects confirm, men who do not conform to models of long hours and overwork can also encounter bias and career penalties.

The two male architects quoted earlier in this chapter discussed the organisational perception of fewer working hours as a sign of reduced commitment. The careers of non-conformist employees can be retarded by the de-skilling and marginalisation that accompanies flexible work.26 Employees working non-standard hours report a range of penalties including lower earnings, slower career progression and loss of skill, as workers were moved onto lesser tasks or failed to gain access to new, higher attributes. A male manager’s comment from the Parlour survey affirms the negative perception of part-time architectural employees: ‘Part-time workers do not provide the focus on full-time project progress for us – we tolerate them when they are in low level exposure to project demands, but our clients demand attention. We give it to them and that is one of the secrets of our success.’

Career Norms

An architectural culture that prizes full-time workers, accompanied by intransigent attitudes to flexible work practice, curtails women architects’ engagement. These issues now increasingly affect male caregivers.27 Many women move between full-time and part-time positions over the course of their working lives.28 Career interruptions and periods of part-time work dominate women architects’ professional paths. A 2004 British survey reported that two-thirds of women in architecture had worked part-time at some stage in their professional life.29 The 2012 Parlour surveys of male and female architects recorded twice as many women respondents documenting a career break of six months or more (43.5% of women and 20.6% of men). For men, the most common reason for taking time off was travel (almost half the men), while almost half of the women surveyed had taken time off to care for children or other family members. Many female architects have ‘portfolio’ careers, moving in and out of employment within the profession, as distinct from the traditional, continuous ‘climbing the ladder’ employment model of previous generations.30

Women caregivers and some men can be heavily affected by the symbolic construction of career ‘interruptions’ and absences. Even brief periods of workplace absence have an accumulating effect on the forward march of careers. A woman respondent to the Parlour survey stated, ‘I’m simply not able to carry out my previous level of responsibilities as the office sees part-time very differently to full-time. I wasn’t given the same opportunities. I would have liked to be more challenged and utilised. I could have taken on more than I was given. I repeatedly asked for more but the partners seemingly didn’t know what to give.’

Women’s ability to move successfully between full-time and part-time work is crucial for career maintenance but architects report significantly lower rates of part-time work in comparison to other Australian professions.31 In Australia 13.5% of men and 43.25% of women aged 20–79 are employed on a part-time basis, compared to the architectural profession’s rate of 12.43% of men and 28.1% of women.32 The qualitative written responses quoted throughout this chapter affirm the presence of flexibility stigma in architectural workplaces. This value system erodes attempts to introduce non-standard working hours and retards the career progress of those who work outside schedule norms.

Data from the 2011 Australian census showing lower rates of part-time work in architecture

A longstanding response to intransigent architectural work schedules has seen women employees depart from inflexible workplaces to start their own practice. As one Parlour survey respondent with three young children commented, ‘I could not work to short deadlines arbitrarily imposed by the principal, work part-time or attend mandatory breakfast meetings. They waste a lot of time and wouldn’t allow me to work from home. That’s why I am a sole practitioner’. The Parlour survey confirmed earlier British findings that a high number of women architects leave firms to start their own practices and reject some traditional career norms.33 This is not always an active or positive choice when women find themselves ‘pushed out’ of mainstream practice.

What can we do?

The predominance of women directors in successful small and solo firms contests the mainstream argument that only ‘on demand’ employees can best carry out architectural work.34 Women professionals in small and medium practice control their schedules and meet the challenges of project-based work and construction deadlines. In 2016 the Australian Institute of Architects Gender Equity Taskforce convened a public seminar to share knowledge of flexible practice in medium and large-scale firms. Four architects presented the case for flexibility, arguing that change must occur in belief systems and work practice. Readers seeking more detailed guidance on flexible and part-time processes can also consult the Parlour guides (freely downloaded at www.archiparlour.org).35

All four flexibility seminar speakers affirmed the value of effective measurement of the quality of an employee’s work, rather than a reliance on perception. ‘Measure output not time at the desk’, declared Leone Lorrimer, the CEO of dwp/suters. ‘Face time’ is not a reliable marker of efficiency. Architecture could follow the lead of business analysts who inquire into successful measures of productivity and retain scepticism towards a quantitative measure of hours worked.36 Ernst and Young’s July 2013 study of Australian male and female part-time and full-time workers concluded by asserting that part-time women workers are 3.1% more productive than their male part-time counterparts and are more productive than their full-time colleagues.37 At the architectural flexibility seminar, recruitment consultant Misty Waters anecdotally affirmed the efficiency of part-time employees, noting that they tend to be more conscious of their limited work time and so curtailed time spent on Facebook and personal administration.

In a period of reduced profit margins the economics of practice demands attention. Leone Lorrimer urged businesses not to ‘routinely price many free hours into their bids’, such as the practice of frequent competition work reliant on unpaid hours. Decision making on staff hires can also be a cost saving if employers consider the cost value of a senior person who can work a three- to four-day week at the equivalent salary of a full-time junior.38 Three of the four presenters noted the economic penalties produced by high female staff turnover. Patrick Kennedy, director of medium-sized practice Kennedy Nolan, stressed the value of his long serving staff, remarking that they possessed the embodied intellectual property of the firm, knew the organisation’s office systems, were familiar with the practice design approach, and could quickly train junior staff. In his practice all staff – regardless of gender or caregiver status – were offered the chance to work flexibly. Kennedy Nolan was committed to building an office culture of trust, equity and collegiality. Misty Waters also observed that offering flexibility to everyone – to accommodate tutoring, studying, picking up kids, etc. – reduces resentment towards working mothers.

The practicalities were tackled. Firms were advised to instate efficient and flexible pay systems to accommodate changing circumstance. For example, an hourly rate system can be offered for a period of time to a staff member at home on maternity leave who is available to undertake QA reviews on documents. Office technology can support staff working at home. IPhones and laptops provide access to office files. Misty Waters advised managers to assess the inherent knowledge embedded in a staff member and use this assessment as the basis for ‘thinking laterally’ about how this embodied knowledge can be used in a part-time capacity. Part-time employees can upgrade marketing material, rewrite manuals and policies, review employment contracts, undertake client reviews, update the website and undertake recruitment activities. These tasks are not necessarily suitable as long-term roles but they are ideal for an experienced employee who knows how to consult in the office and is undertaking a transition back to work. If an employee undertakes these maintenance tasks it can free up director time.

Misty Waters addressed the key issue of how part-time workers might effectively undertake project work. She noted that these staff members should be available for at least three days per week and proceeded to describe a successful project where the fee didn’t support a full-time architect so an experienced part-time architect was allocated to the job. This architect worked extremely well with the builder during the 12-month site phase and regular, fixed meeting times were established between architect and builder in order to comply with the architect’s childcare days. The project architect subsequently moved on to a four-day working week. Misty also recommended teaming a part-time project architect with a strong second-in-command and ensuring the project leader has a mobile with Internet access for ease of checking emails. Finally she noted that there will be times when a part-timer may be in a more junior role than formerly, but the long-term ‘payback’ is reduced turnover and continued motivation.

Although the work/life debate and flexibility research has centred on women caregivers, this focus has expanded in recent years to include male parents. Now the debate is broadening once more to advocate part-time and flexible work as a means for retaining older workers in a time of reduced pensions and longer life spans.39 These changes in work practice can only occur if entrenched attitudes and behaviours are consciously confronted and transformed. Flexibility stigma appears to have stymied the adoption of non-standard work practice. Professional passion and commitment are poorly measured by ‘face time’ and ‘long hours’. The moral value of self-sacrifice has little bearing on profit margins, employee retention, reduced costs of retraining and recruitment, and more collegial organisations. Some default ways of working in architecture – the routine pricing of free hours into fee bids and frequent free work for competitions – as well as poor project organisation compound the problem. If the open-plan office is both a mechanism for fostering teamwork and communication and a surveillance system, reducing resentment of flexible workers by making flexibility available for all and building cultures of collegiality and commitment based on trust and responsibility can tilt the meaning of the open-plan office towards a more optimistic vision of collaboration and connection.