Queer urban theorists David Bell and Jon Binnie state that inherently democratic space is that which resists commodification and purification, and enables identification and opportunities across class and racial boundaries.1 Queer amenities include public toilets, bathhouses, and ‘cruising’ areas, and are described as ‘authentic’ alternatives to ‘commodified’ spaces such as expensive bars or tourist shops. From this perspective, the queer British pub, articulated by theorist Johan Andersson as a ‘counter-cultural response to marketed cosmopolitanism’, can also be defined as a democratic queer space.2

Through the analysis of the democratic queer pub and its eradication in the contemporary urban sphere – and examining how queer culture is responding, or not responding, to homogenised gentrification and its discriminatory effects – the evolution of broader representation for all minority and subversive identities in the built environment, including women and ethnic minorities, can be better understood.

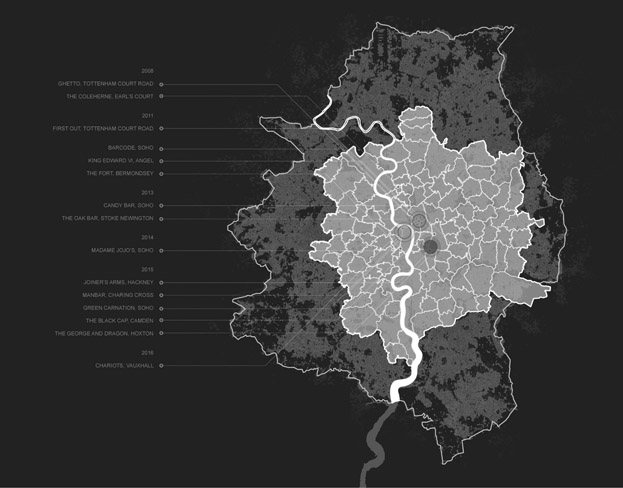

According to Cliff Joannou, editor of gay male lifestyle magazine QX, ‘25% of all LGBT venues have closed in the capital since the [2008] recession’.3 Recent closures range from Vauxhall’s hedonistic super-clubs such as Area and gay male sauna, Chariots, to popular lesbian hangout Candy Bar and drag queen haven Madame Jojo’s in Soho, and have also claimed popular venues in East London such as the Joiners Arms and the George and Dragon. Tony Butchart-Kelly of the Albert Kennedy Trust described recent events as a ‘closure epidemic’.4 Notably, according to Amin Ghaziani, author of There Goes the Gayborhood, the venues that appear to be diminishing at the fastest rate are the bathhouses and leather bars: the democratic queer spaces. These establishments are being replaced by ‘wine bars, straight-friendly martini bars and fine olive oil stores’ as we move further into an era defined as ‘post-gay’.5

Mapping of London’s closed queer venues (2008–2016)

Responding to the Closure Epidemic

As an architecture student and a pseudo-drag performer, I have objectively and subjectively examined the effects that the closure of all types of queer typology have caused – in particular, the establishment of campaign groups for the protection of community buildings. However, it is interesting to note that only the disappearance of queer pubs has sparked direct action. In 2014 and 2015, several queer campaign groups were forged by activists and punters once the imminent closure of successive pubs was announced.6 Groups such as RVTFutures (discussed in Chapter 20) succeeded in preventing the closure of community strongholds through various means, including the process of applying for ‘asset of community value’ status. Campaigns such as Friends of the Joiners Arms and We Are The Black Cap – supporting two of London’s most renowned queer pubs – continue to fight to reinstate their establishments long after the doors have closed.

#WeAreTheBlackCap protest, 24 March 2014, photographed by author

The decision to mobilise exclusively suggests that pubs are valued more highly within the queer community. And if the queer pub that is being fought for is one based on democratic principles, then it is this type of business model that is valued over other forms of commodified spatial typology. It is this observation that has served as the springboard for an investigation to better understand the importance of egalitarian space and the implications of its eradication.

In order to test this thinking, I intend to consider the queer pub as a democratic socioeconomic model, cultivated by the services that it offers and strengthened by the heritage attributed to buildings. Secondly, a model of regeneration will be tested against the histories of London’s queer neighbourhoods to better understand how the years following the 2008 recession have cultivated an inhospitable environment for the democratic queer pub. Finally, the chapter will reflect on the future of the queer pub and whether it is still vital to the maintenance of the evolving queer community. The purpose of this exercise it to ask what can be learned from London’s historic queer pubs: what important principles do they advocate for wider society that are increasingly at risk of being lost altogether.

A Brief History of the British Queer Pub

As ‘crucial sites of community and belonging’,7 traditional British pubs, which have long been bastions of national culture, were appropriated after the Second World War during what Ghaziani describes as the ‘Coming-out Era’.8 As a result, queer pubs are indistinguishable from their heterosexual counterparts, building upon a legacy of queer spatial appropriation that ‘transforms what the dominant culture has abandoned’9 and pioneering examples of inclusive leisure space at a time when most social interactions were organised around patriarchal principles.

Walking tour of London’s queer neighbourhoods, 19 October 2015, photographed by author

Unlike many queer bars and clubs that are located in concentrated urban nodes, queer pubs form a small and diffuse network, littered throughout the marginalised, cheaper areas of the city, often associated with ‘the discarded, the derelict – the ruins of the urban landscape’.10 Lease affordability permitted queer pub managers to operate business models that prioritised community over financial gain: reasonable prices for customers and high salaries for employees. For example, the Joiners Arms was the first pub in London to offer the Living Wage in 1996, setting a precedent for employment equality at the beginning of New Labour’s term.

The Democratic Pub Model

Community and employee prioritisation was not always a guiding economic principle for London’s pubs. During an interview conducted with Ingo Cando, event founder at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, she recalled how the popularity of queer pubs was consolidated during the 1990s and 2000s in an era described as an ‘explosion of queerness and open mindedness’.11 It was during this epoch that a business model founded on democratic principles emerged.

Joel Sanders states that, ‘Queer space carries the promise of a negotiated place united in diversity’.12 Whilst this was not the case for many queer ‘consumption spaces’ that operated exclusionary processes on the basis of characteristics such as race, class, age, or gender, queer pubs typically promoted democratic ethics that can be distilled into three fundamental characteristics, described below.

1. Identity and Belonging

According to journalist Stuart Brumfit, ‘old men’s pubs’ were the only environments in which one could find a ‘real sense of identity’, where customers could assert their own identities rather than be influenced by the behavioural codes and culturally determined rules that divide society.13 As such, the queer pub provided exposure to a diverse cross-section of society within an environment that did not aggressively promote the consumption of alcohol.

This sentiment is supported by Andersson’s description of the Joiners Arms pub in Shoreditch as seeming ‘authentic’ in comparison to other local bars, as a result of the coalition formed between the working class community of the East End and the local queer community.14 The mixing of marginalised social groups rearranges hierarchical structures and translates them into a defiant, self-affirming united group, cultivating an environment in which one can ‘learn your queerness’;15 in effect, learn that alternative modes of being are available outside of systemic hegemony.

2. A Matter of Choice

During an interview conducted with Jonny Woo, co-owner of The Glory pub in Haggerston, he described how the internal facilities influenced the spatial practice. Architectural features also aid the democracy of queer pubs. Large stages, adaptable seating arrangements and separate bar and dance floor areas are aimed at offering customers choices when entering the venue.16 Similarly, the entertainment variety – from burlesque to cabaret – is central to the programming of events, and appeals to a much wider demographic than more mainstream bars or clubs.

3. The Social Network

Finally, queer pubs provide access to wider social networks. For example, Royal Vauxhall Tavern, the first queer building in the UK to be awarded a Grade II listing, provides a range of community support beyond socialisation. From funding a safe house in Uganda for persecuted queer people and weekly community news announcements to burlesque classes for the isolated elderly, Female Masculinity Appreciation Society, and regular HIV testing, such resources are intrinsic to the programming of queer pubs and create an accessible environment for a range of different needs.

Still from Ladies, Gentlemen and Beautiful Wotevers, Documentary Short about Bar Wotever and the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, December 2015

Consolidating the Democratic Model

Contrary to Reed’s description of queer space as the temporary ‘appropriation of the public realm’, the longevity of many pubs in London exemplifies how certain buildings were considered to be immovable components of the urban landscape. For example, the earliest records of The Black Cap date as far back as 1752. In this respect, queer pubs can be paradoxically regarded as examples of ‘concrete queer space’.

Developing this further, while the combination of diversity, variety and community support delineates pubs from other queer typologies, what separates pubs from other forms of democratic queer space, such as community centres that may offer similar services, is their heritage: having existed as part of the urban fabric for generations.18 It is this attachment to queer history that ‘becomes the only complicit official urban value’19 and allows us to better understand the emotional attachment of punters, which has led to the formation of campaign groups.

The Closure Epidemic

Since the 2008 recession, there has been a notable clampdown on democratic spaces exclusively for queers.20 Regardless of the causes, desexualised forms of consumption have replaced threateningly sexual forms of queer space in what Andersson refers to as an ‘attack on sleaze’.21 However, according to Joannou, the ‘chipping away’ of the queer scene is a cyclical phenomenon. From the aristocratic bohemianism of Earl’s Court in the 19th century to a similar ‘closure epidemic’ of queer venues in East London in 2003, ‘the gay scene has always found new ways to move with the times’.22

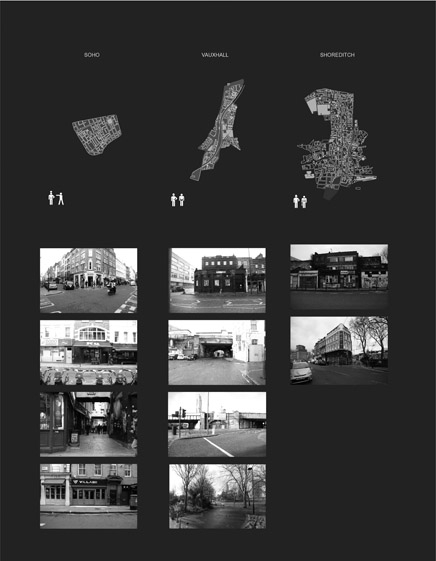

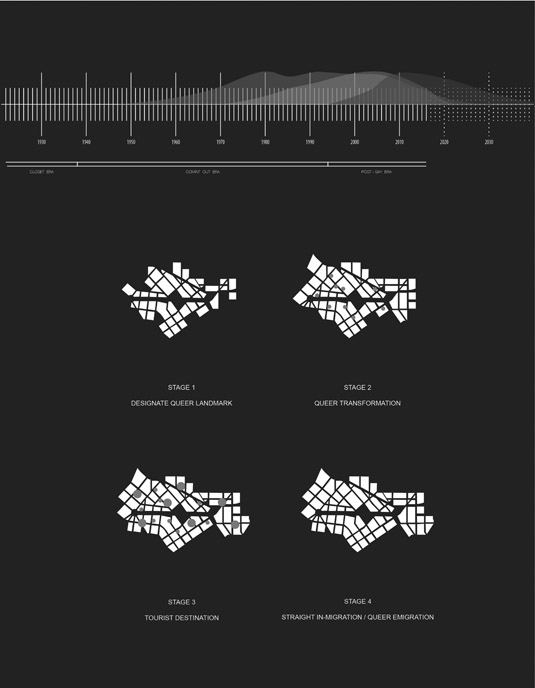

Drawing from these trends, theorist Alan Collins has distilled the cyclical dynamism of queer locales into four stages.23 Initially, areas that have a queer drinking establishment attract other services, vendors and queer customers to the neighbourhood. These services widen in size and scope as the influx of queer residents continues. Eventually, the area becomes known as a queer tourist destination, or what Ghaziani terms a ‘gayborhood’.24 At this point, the cosmopolitan authenticity of the environment attracts heterosexual consumers and investors seeking to exploit cultural capital, leading to the final stage of queer emigration that moves on to appropriate new territory.

Model of queer neighbourhood rise and demise

The recent histories of London’s queer villages, Soho, Vauxhall and Shoreditch, accurately follow this model. For example, the renovation of Soho in the 1990s, following the AIDS epidemic, aspired towards a ‘sanitised version of gay culture… around commercial interests’.25 In the case of Vauxhall, which, ‘to some extent became a tolerant zone in which not only sex-on-the-premises, but also relatively open drug use, had become more accepted’,26 the past several years have seen the nearby Nine Elms Regeneration scheme force many underground queer businesses to close down owing to unaffordable rent increases. However, the transformation from the third to fourth stage of Collins’ model (from celebrated gayborhood to lucrative investment opportunity) is epitomised in the closure and repurposing of the Joiners Arms in Shoreditch into a large-scale, luxury residential scheme.27 Across the capital, queer space, which transgresses class and racial boundaries, is being replaced by inaccessible businesses targeted towards narrow demographics. Here, not only does the city observe a transition of physical amenity from democratic to commodified, but the notion of queer identity moves towards conformist respectability.

The New Homo-Normativity

The commodification of sexualised space as a ‘global repertoire of themed gay villages’ is seemingly also reflected in the commodification of not only the queer condition but all forms of subversive identity, manifest as depoliticised, demobilised, assimilated consumer; indistinguishable from the heteronormative capitalist ideal.

Whilst closure epidemics of queer venues are not unusual in urban history, this contemporary development in the human condition is unprecedented. Journalist Daisy Jones speculates that this ‘rapid transformation’ may be a result of budget cuts implemented by the Conservative government, increased toleration of homosexuality, or the rise in online dating.29 I have identified this as the ‘Triple A Phenomenon’: Austerity, Assimilation, and Apps. In this new context, Cook suggests that ‘the model of the gay pub from the 1990s’ is no longer sustainable.

Where Next?

The democratic business model of London’s historic queer pubs has recently become subject to the threat of regeneration, labelled as unsustainable in the contemporary socioeconomic climate. However, this shift is indicative of wider trends that affect all forms of radical or subversive identity which challenge the neoliberal human condition. The democracy that guides this model, including principles of diversity, entertainment and support, should not be regarded as a set of rights bestowed unto an oppressed minority, but as operating guidelines that can be accessed by anyone. Such principles align themselves against many forms of nightlife venue in the capital that operate processes of exclusion guided by drivers of consumerism, yet they are becoming increasingly difficult to locate. In this way, what is at risk is not simply an environment treasured by a sexual minority but an exemplary use of spatial appropriation, both morally and ethically, in which alternative forms of identity are not only practised safely but are celebrated.

Under the guise of a ‘new homonormative’ post-gay lifestyle, difference becomes pathologised. While homosexuality enjoys greater acceptance nationally, deviating from other norms, such as binary gendered identity, is criticised. In the same way that the gendered urban struggle is far from enjoying equal rights, greater privileges should not be accepted as ‘good enough’.

Elsewhere in the globalised west, many gay villages have been protected by local legislation and heralded as tourist destinations. This does not seem to be the case for London. If the capital becomes entirely homogenised, then alternative modes of being cannot be experienced or practised. Both heteronormative and homonormative conditions should have access to what the gay liberation movement fought for: that is, the acceptance and celebration of difference, rather than the assimilation and distillation of it.

So what can be done? The emergence of temporary queer nights supports the idea that queer culture will always find ways to thrive against adversity.30 However, many of these nights are described as being inaccessible for a varied demographic, particularly older generations who do not want to go a place that is designed around the consumption of alcohol. Nevertheless, while the three fundamental principles of democratic queer space can be replicated anywhere, it is the heritage and the permanence of ‘concrete’ spaces such as pubs that serve to consolidate these safe environments.

While Jonny Woo, co-owner of The Glory, has struck a deal with his friend and owner of the freehold to ensure rent control, perhaps we can propose a scenario in which permanence and temporary appropriation can exist simultaneously. My Masters has led me to explore this scenario: a mode of escape outside of the processes of regeneration by modifying a transportable structure and claiming it to be queer, aspiring to operate the democratic principles outlined. This is by no means an attempt to solve a crisis much larger than a single intervention, but for me it opened up a dialogue as to how we should try to consider breaking the cycles of gentrification and queer cultural exploitation – not just for the queer minority but also for all ethnic, sexual and gendered minorities whose territories attract investment that eventually leads to displacement. Much can be learnt from the structure of London’s 1990s queer pubs and if they can no longer exist in the contemporary socioeconomic climate then we must strive to establish new forms of subversive environment inspired by their democratic principles.

As the trigger for this investigation, the existence of queer campaign groups that appear to be fighting a losing battle is perhaps more symbolically significant than practically effective. According to Ghaziani, ‘Acts of queer cultural preservation and resistance make sense as life-saving, identity-affirming and community building’.31 The #WeAreTheBlackCap campaign group continues to demonstrate outside the boarded up pub every Saturday, despite the recent planning application that asserts that the pub will not be reopening as an exclusively queer venue but as a ‘Soho House-style’ late night bakery and bar. This example epitomises the threat facing the model of the democratic pub of the 1990s and 2000s. However, against apparent futility, the community are still willing to fight for a space in which they can access a defiant, self-affirming and diverse community, a space where social services are provided, a space within which they can ‘claim their own identity’.32 If we better understand the reasons behind the fight to safeguard these buildings then we learn that space which provides the principles of democracy within a capitalist framework is necessary if we are to try and protect the right to celebrate, as opposed to assimilate, difference.