Gender Performativity and Architectural Education

The path that feminism forged has given young women access to higher education such that men are no longer the majority in many university courses. Beginning in the 1990s, female students increased in numbers to the point that, in countries such as Austria, Canada, Iceland, Norway and the United Kingdom, they now outnumber their male counterparts in universities.1 The growing participation of women students in higher education has succeeded in giving more gender parity in terms of access and representation of numbers but the pedagogical framework in some historically male dominated disciplines in higher education, architecture included, has not modified to respond to the gender shift.

Because many women architects leave a career in architectural practice entirely, there remains a lingering gender problem that researchers in architecture grapple to understand and solve.2 Curious is why many women students who have better attainment in secondary school do not progress as well in their architectural studies or in their post-university work as practising architects or as architectural educators. In both workplaces women are recognised, promoted and remunerated less than their male colleagues. It is the aim of this chapter to tease out some of the reasons for lack of equal gender progression. It does so through analysis of the relationship between gender and architectural education, from entry to graduation, in order to reveal how the performativity of gender at university influences an individual’s prospects to acquire optimal social, cultural, and economic capital in their post-university working life.3

According to Judith Butler, gender is not ‘a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts proceed’; instead it is constructed socially over a lifetime and performed as ‘a stylised repetition of acts’.4 Butler sees biological gender and sexuality as part of the behaviour that defines a person. Her theory of the enactment of gender proposes that the performativity of gender can be feminised or masculinised according to how and where a woman or man ‘practises’ their sexuality in everyday life. ‘Genderisation’ in architectural education ‘deals with issues of power: who wields power, how power is attained’.5 In architectural education, pedagogical power is exerted from the moment a prospective student chooses to study architecture.

Gender and the Choice of Architecture

When looking at the global workforce, both economists and sociologists agree that ‘gender is linked to career outcomes’.6 Sex differentiation, stratification, and stereotyping that develop through an individual’s life construct gender identity. Gender identity in turn constructs a sexual division of labour and sex segregation of occupations due to its association with (the limits of each gender’s) ‘social mobility’.7 While the decision to study a design career at university, for both sexes, often centres on an interest in creativity – a practice that is generally considered gender neutral – according to Clegg, Mayfield and Trayhurn prospective women and men students choose alternative career paths in design in higher education.8 The reasons for choosing a particular design career are based on ‘perceptions of dominant disciplinary discourse’ framed within the public cultural realm.9 For instance, the decision to study product and furniture design (where women are underrepresented) versus fashion and jewellery (with an overrepresentation of women) ‘reproduces the stereotypical dualism whereby women are associated with the body and the decorative, and men with technology and the shaping of nature’.10 Clegg and Mayfield argue that, ‘There is a complex relationship between disciplinary [design] cultures and gender’.11

The reasons for choosing an architectural education broadly parallel the reasons for choosing a career in design.12 Architecture is perceived by the public, and presented to them in the media, to be a creative career. It is a discipline that carries with it an image of social esteem, societal contribution, and potential professional fame. In addition, it is seen to be practical, profit making, and leading to secure employment, the latter being the reason that some students choose it over studying, for instance, fine art or art history. There is a public perception that architecture offers a less gender specific career than, for instance, interior design or engineering – operating somewhere in between and around (what are perceived to be) female dominated versus male dominated careers respectively. It is also considered to be a job that can be practised from home, not only the office, thereby giving a sense of workplace flexibility. It is a career choice that suggests ‘you can have it all’.

In the United Kingdom and United States women are now undertaking a vocational architectural education at university at a rate mostly equal to or greater than men.13 While architecture schools undertake their own internal assessments on gender split and recruitment, there has been negligible academic research done to assess how a prospective student’s gender influences their being offered a place or not. Nor has there been much research on the way the interview process might be affected by the interviewee’s and staff interviewer’s performance of their respective gender identity. If a student is accepted, the school of architecture and university they are accepted into, and the stage of life they are at, frames expectations of their performativity as an architecture student. So the question is, does gender impact on a student’s architectural education? And if so, how? ‘How do educational systems [in architecture] generate, reinforce or alter gender divisions and what, if anything, should [and can] be done?’14 In order to investigate how gender is enacted in architectural education, pedagogical practice is examined here in relation to the different types of architectural institutions, workforce structure, demographic and division of labour, and curriculum structure and content.

Gender, Division of Labour and Institutional Structures in Architectural Education

While some of the canons of architectural education have endured ‘in design education since the École des Beaux Arts (School of Fine Arts) in Paris in the 1890s’ the framing and enforcement of them varies depending on the ethos of each school.15 In untraditional schools of architecture, which are curiously often the most reputable, contestation of architectural norms is purposely encouraged by the teaching staff – female and male – and is seen as a way to radically reinvent the discipline. This contrasts with traditional schools of architecture, where architecture managers and educators, in conjunction with professional regulatory bodies, define the curriculum tightly and create systems of assessment that ensure quality and compliance by students to meet assessment criteria for real world, vocational practice. As Paolo Tombesi notes, ‘Discussions around work in architecture tend to fall into two separate domains: one concerned with the theoretical, socio-cultural definition of intellectual pursuit; the other preoccupied with the operative, managerial, and eventually (under-) remunerative aspects of the metier. The difference in focus implies a different framing of the architect as the subject at the centre of the analysis: individual political agency on the one side, service provider collective on the other’.16

How architecture schools appoint their academic workforce depends, arguably, less on the sex of the employee than on a synergy between the school’s ethos and that of the educator’s. But research suggests that women educators in architecture are disadvantaged more than men and that there is a gendered division of academic labour (teaching, administration, and research). Some findings indicate that, ‘There is a clear bias against women’s employment [in the university]. They were on short contracts without overlap or on hourly rates which meant they were not eligible for benefits such as maternity pay or pensions. There were questions about problems women had getting promotion in certain schools and there is a perception that there is a glass ceiling.’17 The same research evidenced that there is a gendered division of labour in curriculum delivery, where, ‘Women tend to do the arty/history side, men do the technical science side’.18

An architecture curriculum comprises the study of theory and design. Theory lecture courses centre mostly on reading and writing and women students tend to perform better in history and theory modules, with male students tending to be stronger in technology, digital representation, and management practice and law. But the predominant percentage of an architectural education occurs in learning architectural design through practice-based teaching done in the design studio where students produce drawings or visualisations or undertake the ‘live project’ building of their design(s). A form of ‘tacit-learning-in-action’, male students tend to perform better in design studio, although this is changing.19

A design studio is still led by a studio ‘master’ (who can be female or male). That studio lead collaborates with another studio tutor, with equal or less teaching experience. Design studio tutors, which historically were always male-male couplings, have transitioned to being more male-female teaching teams but less so female-female teams, although the latter is increasing. The two tutors establish a focus of architectural design study and practice through a self-defined ‘studio brief’, which is used as a framework through which to teach and assess each student’s design response. Design tutoring is often done by early career academics – female and male – because it allows them to work part-time or casually in order to share childcare labour and/or supplement their income (from work outside the university in architectural practice). If they enjoy the experience they can become more and more embedded within the school, becoming permanent. If their practice career becomes (financially) healthier they will typically opt out of studio teaching.

Unlike lecture courses that are delivered to a large group of students (and where it is less possible for educators to get to know students personally) design studio is taught to small groups of students on a one (student) to one or two (tutors) basis. Working relationships are close. When students are given the option to choose their studio educators, preference favours the tutor(s) whom students deem more suitable to work with, is more experienced, or to whose studio theme they are more attracted.20 Familiarity or reciprocity of architectural ambitions manifests differently for female and male students who identify differently with female or male tutors.21

‘How teaching leads to learning’ is generally not understood.22 In an architectural design studio the learning experience is even more complex because the content of what is taught in design is so varied and undefined, as are the modes of pedagogical practice. Arguably traditional schools of architecture tend to be more prescriptive, with more hierarchical teaching structures to manage large numbers, while untraditional schools of architecture are less prescriptive with fewer students to teach. An architectural educator’s mode of teaching and pedagogical framework is usually contingent on her or his own experience of architectural education – they normally replicate it if it was positive or modify it if it was not entirely to their satisfaction. Studio teaching and learning occurs in an abstract, non-linear manner that does not relate to the delivering, examining and absorption of precise fixed content. In the ‘transitional space’ of architectural design studio teaching there is a complex ‘blurring of what comes from the teacher and what comes from the student’ and, I would add, what comes from the teacher’s teacher(s) to the teacher.23 Daniel Lindley argues in This Rough Magic: The Life of Teaching that ‘successful teaching… has to do with what is already in the student’24 and that ‘the aim of teaching is to be “the right teacher at the right time” and that both the curriculum and the teacher need to resonate with the pupil’s inner states’.25 Still, for more traditional schools of architecture this egalitarian attitude to education is not always supported. In addition, the gender and age of the student and the tutor(s) impacts markedly on whether an educator encourages or allows a student to resonate with their inner states or not. This is because the design studio is the main site in which a student is disciplined into becoming an architect, where they learn ‘the game… [and] rules’ of the profession.26

According to Kathryn H. Anthony, the design studio is much like the laboratory situation that university science students operate in, in that they learn and evolve as a group.27 In The Culture of Professionalism, Burton J. Bledstein notes that professions begin to form much like a sorority or fraternity (or college in the UK) did in the 1820s in the US, which ‘made it possible for the individual to find both privacy in his lodging and intimacy in a small group – a second family’.28 Participation in an architectural studio replicates this kinship model. A studio culture either supports all students in the group or not, depending on their performance in design tutorials or crits.29 As George Henderson and Jeremy Till argue, the crit (or review, or jury) ‘marks a rite of passage, the moment when one crosses over from being one of them to one of us’.30

Tonia Carless, Final Crit, Year 6 Postgraduate Diploma in Architecture, June 1990. Photograph by Jane Tankard

Unlike weekly design tutorials, which take place informally around a table, in design ‘juries… students present their completed design work one by one [by standing up beside it as it is displayed on a wall] in front of a group of faculty, visiting professionals, their classmates, and interested passers-by (see figure on previous page). Faculty and critics (usually seated in lines facing the student) publicly critique each project spontaneously, and students are asked to defend their work’.31 ‘A review can be positive or negative, creative or destructive, enlightening or deadening, encouraging or shattering.’32 The ‘chaos’ leading to some students leaving ‘the scene distraught, angry and humiliated over their own poor performance and loss of control of the jury’ puts those students in a weaker social position in studio culture.33 The crit presentation and reaction to criticism is part of the ‘game’ of architectural education. Performing well in a crit is a potential sign of professional success. Crucially, the way a student performs their gender and sexuality in terms of their verbal communication and self-presentation in design studio tutorials and reviews with design educators and critics (female and male) has a large impact on their socialisation into architectural life and subsequently their ability to accrue educational capital.

Gender and the Acquisition of Capital During Architectural Education

‘A student’s level of… capital and the organisational habitus of the architecture programme’ are primary factors in the study of ‘the subject of socialisation in education’.34 Pierre Bourdieu argues that education is the place in which one begins to accrue social, cultural, and economic capital. Taking inspiration from the work of Karl Marx, Bourdieu explains that: ‘Capital is accumulated labour… which, when appropriated on a private, i.e., exclusive, basis by agents or groups of agents, enables them to appropriate social energy in the form of reified or living labour… It is what makes the games of society – not least, the economic game – something other than simple games of chance’.35 Of the three forms or guises of capital (economic, cultural, and social) Bourdieu contends that schools are the sites in which ‘the hereditary transmission of cultural capital’ occurs.36 Knowledge of any field – which has the potential to gain economic capital – has historically been transferred in architecture schools through the social capital invested in ‘master-pupil chains… The more eminent the master, the greater the capital that can be transmitted’.37

The master-pupil chain relies on students pleasing their tutors, reaffirming the values and framework that their formerly mostly male, now more and more female, tutors present to them. In ‘Understanding Architectural Education’ Stevens addresses how this nurtures a spirit of competition, which has been seen by the profession as a positive and enduring characteristic of any emerging architect. ‘Competition creates a whole symbolic market whereby students can show their dedication to the game.’38

Competition occurs also between architecture schools, and the inherent structure of knowing and gaining an education at the ‘best’ architecture schools enables students attending them to build stronger influential networks to aid and direct their career in the future. The ‘best’ architecture schools claim to attract the ‘best’ design and theory tutors and tend to be better funded so they can attract the ‘best’ external speakers. More often than not, tutors bring their ‘best’ students back to teach with them so strong lines of ideology or style are carried through the master-pupil chain.

Competition and endurance as an enactment of workplace relations is neither ahistorical nor a-cultural. It is a gender-biased practice. According to Anthony, ‘The competitive model of design education is very much a male model.’39 Historically it was about male tutors and reviewers using covert strategies to assert their power to abuse, denigrate and bully students, of both sexes, which can in turn lead to a form of student ‘masochism’ – being gratified to endure the abuse.40 American architect Steven Izenour explains

‘The athletic and military analogies that many design instructors routinely use in design studios can be a sore spot for women students… and may offend some gay scholars. Many women are simply not involved in sports at all, except for individual exercise programs where the purpose is to develop one’s own physical abilities’.42 Anthony contends that the competitive nature of design studio as enacted most extremely in design juries, where students are made vulnerable through the need to defend or fight for their design position in public, is disconcerting for many female students who suffer an ‘emotional toll’ that affects their confidence and powers of assertiveness.43 ‘Fear and anxiety as driving or motivating forces appear in many psychoanalytical accounts of gender identity, both male and female. For example, Rosalind Coward (1992) locates anxiety at the very heart of female identity, as the expression of a deep set of problems and contradictions and the search for impossible goals or objects’.44 The difference between how women and men manage their emotional performance under stressful situations – whether they cry openly or not – contributes to non-competitive women and male students being required to ‘man up’, to shift their behaviour to ‘masculine standards’.45 Another, potential form of disciplinary (and disciplining) criticism that is flattering or promotional is seen to be less effective because it is at odds with a historically embedded pedagogical practice of negative criticism.46

The extreme amount of content that is covered in an architectural course, and the fact that radical pedagogical practice can involve unlearning everything a student has already learned in an undergraduate course, means that a student’s stamina – mental and physical – is always being tested. Many of the ‘best’ architecture schools in the world advocate an excessive long hours work ethic and students are discouraged from doing anything other than university work. The ‘all-nighter’ is possible because schools ‘allow 24-hour access to studios and computer facilities’ and this can be detrimental to the health and wellbeing of some students who cannot sustain the intellectual and physical energy demanded of them.47 The ‘best’ students exhibit a singular focus on their individual production; they are driven to do nothing but work. They meet deadlines and perform optimally under intense pressure. They are fully committed to a career in architecture. These attributes make them highly employable. How long a student can work can set them on a stronger or weaker path for career success. It dictates their human capital – a phrase defined by the Scottish political economist Adam Smith – where a student acquires expertise ‘during his [or her] education, study or apprenticeship’, which contributes to their ability to be more productive for society.48

Igea Troiani and her father at her undergraduate Architecture degree graduation ceremony, 1989. Photograph by Rita Troiani

Igea Troiani and fellow architecture student and boyfriend, Andrew Dawson, 1988. Troiani and Dawson formed the architectural practice Original Field of Architecture Ltd in 2008 in Oxford, and from 1997 to 2005 were directors in HAPPENiNC studio in Brisbane

Outside their academic endurance and accomplishment, two ways a student can accrue additional cultural capital during their education is through interpersonal relations developed in the studio with either another student or their tutor. In this case, femininity or masculinity is enacted depending on who the student or tutor has sex with. The sexual performativity of gender – lesbian, heterosexual or gay – by female or male students can influence their future architectural careers and that of their academic tutor/educator.

Students studying together and of a close(r) age can form an intimate partnership during their studies. After graduation, and because of their interpersonal relationship, they can decide to found a private architectural practice together (see figure above). In this case, the labour of architecture is enacted professionally and socially, in the office and the home, and sometimes every waking hour of the day as projects are discussed as much over the computer in the office as they are over the dinner table in front of children. While it has the potential to generate strong capital reward, architect-husband-and-wife or architect-partners (heterosexual, gay or lesbian) need more time to accrue capital – through the architecture designed and the image of each partner and the practice – to produce the same extent of capital their professors already hold.

Due to the close contact in the design studio, ‘master’ – female or male – and student affairs can occur. Different generational affairs appear in two forms: an occupational bonus or occupational hazard, and are reliant on social and economic choices based on suitability for both partners. American sociologists Paula England and George Farkas contend that the ‘choice of a partner [can be seen] as a market phenomenon’.49 When the relationship chosen by a student is with a prominent figure such as a professor, and is enduring, the student has the opportunity to gain maximum capital that can be carried during their career. They are able to access established social networks and contacts that other students cannot. If the relationship is fleeting, the outcomes for female or male student, and the tutor, can be detrimental to career progression, leading to either or both experiencing a glitch in, or exit from, their study or career respectively. Educators who have affairs with students can experience a slowing down in their career progression due to the complexity brought into their professional and private life, particularly if they are in an existing relationship or family.

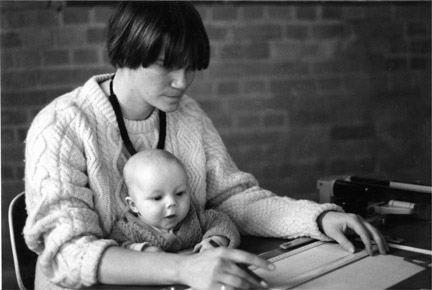

Architecture student Joelle Darby works over her drawing board with her four and a half-month-old son, Alex, on her lap, February 1988. Photograph by Ronnie Maclellan

The choice for love or economic potential or fertility/virility of a partner are important value criteria that impact on the capacity of an emerging architect to create capital. The least economically viable of all is love as it is unconditional, selfless, and altruistic and is not measured in financial remuneration. To fall in love and have a child while studying architecture disadvantages both female and male student parents because they have to compromise the amount of time they can devote to their studies. For architecture student mothers the situation is particularly difficult (see figure above). ‘Students with childcare responsibilities found that often they were expected to stay late for instance for presentations and this sometimes caused problems. Also social events were inconvenient’.50 Any student who has children during their architectural education is forced to work harder than other students and put under more pressure because they have other responsibilities beyond university work. ‘There is concern that some schools may be unsupportive around childcare issues’.51 That concern applies to academic staff parents, too, with architect academic mothers again being disadvantaged over architect academic fathers.52 The inability of universities to factor in the added difficulties facing working parents reflects the inability to understand anything other than a model of ‘masculine’ workplace performativity in higher education. If architecture schools could generate strategies that are empathic to different work-life patterns, i.e. taking into consideration that different genders have other commitments and responsibilities beyond a singular vision centred on university labour, then a better workplace might emerge for women and men architecture students, educators, and practitioners.

Gender, Architectural Education and Capital

While architecture is considered a creative, gender-neutral profession, a gender split in students and educators occurs through the performativity of gender enacted through a ‘hidden curriculum’.53 While the curriculum is evolving, it is because ‘women building and designing today have learned their trade from men’54 that architectural education is based on a historical, ‘masculine’ model of academic thinking and production that favours masculinity, particularly in the theatre of the design studio.

‘Genderisation in architectural education’ in the studio occurs through the favouring of hierarchically institutionalised stereotypical masculine traits – confidence, ambition, singular focus, competition, endurance (intellectual and physical), hard work, productivity, not having children, and understanding the rules of ‘how to play the game’ – and impacts on a student’s and educator’s capacity for social mobility.55

Because power relations between a student and an educator – in labour and in personal or sexual association – are exerted more visibly in the design studio context, the studio is where differences in gender can lead to unequal treatment that can have a knock-on effect in professional practice or later academic life.

So if current architectural education is gender biased, what can be done? The solution lies in the problem: women in architecture.

The feminisation of the teaching staff in the academy or the increase in women academics is seen by many gender scholars in architecture as the way in which to gain gender equitability for students.56 This is achievable when women educators take action through resisting conformity and ‘identify through disidentification’.57 Women academics, if they do not replicate a masculine model of education – the ‘master-pupil’ chain – are better positioned to understand deeply the obstacles that face women students. Linda Groat and Sherry Ahrentzhen argue that ‘women faculty’ or educators are the ‘voices of change in architectural education’.58 Because an architectural educator is not restricted in how and what they teach, women educators in architecture can design the curriculum and where an architectural education takes place – beyond lecture theatres and the studio – for greater gender diversity. They can champion the ideals of a liberal education; forge interdisciplinary connections; encourage experimentation, integrating different modes of thought in the studio; teach principles of visual and spatial abstraction as a connection to other disciplines; establish a communicative environment; reform pedagogical practices in the studio; encourage collaboration; and care for students.59 As anyone in architectural education knows, this is already starting to happen, albeit slowly.

All parties in education need to value women’s (and men’s) labour inside and outside the university. Male architectural educators of an older generation (and women who replicate their model) need to support non-masculinist, inclusive strategies of architectural education, forgoing their professional patriarchal autonomy, and to share, not defend, their power. They need to be more sensitive to the gendered behaviour of non-masculinist female and male students and staff who struggle to manage stress and pressure. They need to develop an emotional register and methods of teaching to accommodate this, and not think less of a student who expresses their working stress through crying. Students – female and male – need to reconsider how they ‘treat their teachers’ and student peers equitably, giving respect and support.60 Some men in the current generation of students are already leading the way, showing empathy and non-competitive, collaborative engagement with their peers, which some argue is the consequence of having working mothers who juggle the balance in work and home life.61 Universities and schools of architecture need to value a work-life balance for their staff and students, not support a pattern of life based on singular focus and long working hours. This is becoming an even more complex task for institutions that are transitioning from institutions for education (Foucault’s ‘premodern or medieval university’) to entrepreneurial businesses (the ‘modern university’). Neoliberal higher education makes stronger demands on its employees and students to consume and produce in a more industrialised, efficient, and voracious manner, through a form of ‘academic capitalism’.62 In ‘Future Investments: Gender Transition as a Socio-economic Event’, Dan Irving ‘confronts head-on the demands of capitalism interested in the whole life of the employee’.63 ‘He is concerned, in particular, with how contemporary workplaces demand that all aspects of the lives of employees – including bodies, minds and psychic lives – are put to work in the interest of the creation of economic value.’64

If we are to reformulate architectural education we need to be critical of the organisational and value systems that underpin architectural education.65 If women and men are gendered through the performativity of their daily labour, from birth to death, then it is through the performativity of feminine and masculine labour equally shared by women and men of all classes and cultures (in all of its varied identities) inside and outside the university that a more sustainable and gender balanced architectural workforce can begin to emerge. Dominant ‘hegemonic masculinity’ is crippling architectural education (and the architectural profession) and needs to be resisted.66 This means the modern university needs to stop sacrificing human capital for economic capital and allow its students and educators to evolve new forms of education that are socially responsible.