Where are the Women?

Early in 2014 six architects gathered for a photoshoot for the BBC television programme The Brits who Built the Modern World.1 Before taking their final positions for the photograph, one of the six was asked to stand aside. The other five protested at this and they all duly posed. When the published photograph appeared, Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Nicholas Grimshaw, Terry Farrell and Michael Hopkins were all there, but where was Pattie Hopkins? (See figures below.) It seems that despite being a partner and founder member of the Hopkins practice this ‘inconvenient woman’ had been airbrushed out.2 When accusations that Pattie Hopkins had been erased because of her gender started to arrive, one response from the BBC was that the original picture ‘had not resulted in a suitable photograph’.3

Six world architects open RIBA Architecture Gallery Reconstruction of photoshopped photograph used for BBC series

Almost a century on from the 1919 Sex Discrimination (Removal) Act,4 which allowed women to become architects, they are still being rendered invisible and excluded from history. Pattie Hopkins is in a line of women whose achievements have not been recognised and applauded. Denise Scott Brown boycotted the 1991 award ceremony when her husband Robert Venturi was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize without her.5 6 One argument against the campaign to award her the prize retrospectively was that it was only ever awarded to a single architect.7 However, checking the list of Pritzker laureates reveals that Oscar Niemeyer and Gordon Bunshaft jointly won the 1988 prize.8 It was not until 2005, when Zaha Hadid won, that the prize was awarded to a woman.

The Past and the Present

In light of the latest erasure of a prominent woman, we wanted to know if anything had changed since 2003 when our report Why do women leave architecture? was published.9 The percentage of women architects in 2001 was 13% and despite the gradual increase in females entering higher education to study architecture, the percentage of women within the profession had barely changed over a number of years. It appeared that the number of women leaving was cancelling out the gains in female recruitment to architecture schools and new entrants to the Architects Register.10 Our research aimed to find out why this was happening, and to make recommendations for actions that would assist in halting the rate of attrition.

Our original research findings indicated a range of issues facing the profession rather than a single factor. Women who had left architecture described a gradual build-up of issues such as being increasingly overlooked for career opportunities and promotion, low pay, long hours and a profession dominated by macho culture. Key factors that influenced women’s departure from the profession came under the umbrella of prevailing culture and employment conditions and were not due to competency issues or loss of interest in architecture. Many were issues being faced by women who were still practising. It was significant that students cited some of the same concerns as those of people in practice, particularly in relation to long hours, and it appeared that this long hours culture was instilled during the education process.

The experiences of female staff and students in schools of architecture were varied, but some important concerns were identified. Students with childcare responsibilities cited the expectation that they should stay late as a problem. One student summed up a concern raised by a number of others: ‘Learning in a completely male dominated environment was very disillusioning and very biased’. One of the most critical comments was that:

The ‘crit’ system, prevalent in many schools, elicited mixed commentary. While there were positive comments that the system could be a valid way of presenting work, issues raised mainly concerned different attitudes displayed towards male and female students. One women expressed this as, ‘Some tutors are less critical towards females’ and considered that this could prevent more detailed constructive critique.

Women represented 22% of teaching staff in the academic year 2000–2001,11 but there were evident variations regarding representation in different schools. One student stated, ‘Our only female part-time teacher has left the department’ and went on to say that she found it ‘hard to work in such a gendered environment’.

One staff member described her university as ‘positively Neanderthal when it comes to equality of employment’. Another cited the fact that, although she had just been promoted to Reader, this was the only promotion among the five women in her school in nine years.

Our report included over 100 recommendations and identified actions that could be taken by schools of architecture, professional bodies, and architectural practices. Key issues to be addressed included long hours culture, sexism, side-lining, ageism, low pay, glass ceiling, macho culture, job insecurity, inflexible working structures, poor employment practice and lack of returner training.

The Aftermath

Several positive steps were taken after or in line with the original publication and there was a willingness in some quarters to progress gender equality. One such initiative, DiverseCity – an international travelling exhibition described as a ‘global snowball’ showcasing diversity within the profession – was effective and ran over a number of years.12 The RIBA Equalities Forum, Architects for Change, and the Women in Architecture group championed many of the recommendations.

In response to one of the recommendations, RIBA set up a specific women returner’s course at London Metropolitan University (LMU) in 200813 but this ceased. LMU is now running a course, RIBA: Practice in the UK Short Course, which is mainly targeted at architects with European qualifications, but also serves as a refresher course for people returning to practice after a break. Apart from a web based resource Women Returners: Back to your future, directed at women from all disciplines and not specifically architecture, there is no significant regional provision despite evident need.14 15

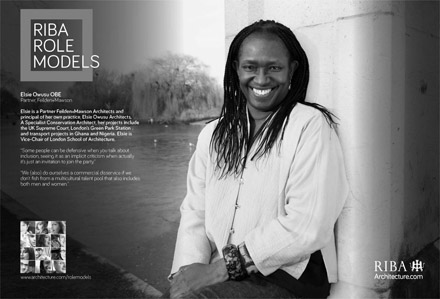

The editing out of Pattie Hopkins and a more recent claim from Elsie Owusu that there was ‘institutional racism at the heart of the institute’, referring to RIBA, indicate that all is not well within the profession. Owusu was made a diversity role model by RIBA in June 2015 and appointed to the RIBA national council in September 2015. However, she subsequently stated that she was ‘absolutely bloody flabbergasted’ by the ‘boys’ club culture’. She went on to say:

Her core claim is that the RIBA president recommended that the council select an alternative candidate for the post of Vice President of Practice and Profession, thereby hampering her chances of being voted into this position. Notwithstanding this, it is clear that her concerns go beyond her own personal circumstances when she implies that the ‘boys’ club culture’ is embedded in the profession and consequently demeans and hampers, among others, the progress of women. A QC has been appointed by the RIBA to look into the allegations, indicating that the matter is being taken seriously.

Elsie Owusu, RIBA diversity role model

Since publication of the 2003 report, women who have left architecture, are taking career breaks, or are attempting to return to the profession have contacted us for advice, often related to the lack of support for returners and the need for flexible working opportunities. Women who have read the report continue to contact us and report experiences that tally with those received in 2003.

These latest concerns, combined with a phone call from an erstwhile colleague seeking advice about returning to the profession, galvanised our decision to revisit the research. We wanted to find out the extent to which the culture both within and outside the architectural profession parallels the attitudes displayed at the photoshoot and reported by Elsie Owusu and others.

12 Years on

In order to gain more insight into current experiences of women who had qualified as architects, we interviewed women architects who had either left or taken long career breaks from the profession. We also looked at the gender profile of the architectural profession compared to medicine and law as well as some other construction professions.

What has Happened Since 2003?

In 2003 14.3% of the profession were female. This figure has risen to 25%, representing an increment of less than 1% per year. At this rate, parity will not be achieved until the 2040s. Data on entry to the Architects Registration Board (ARB) register reveals an even slower rate of increase. Women represented 36% of new entrants in 2014, but between 2007 and 2014 the increase in female registration was only 1.6%.17 This raises additional concerns about future trends while continuing to beg questions regarding the attrition rate. If attrition increases, even the 2040s parity target will be unobtainable. Given that the Office for National Statistics (ONS) 2013 figures indicated that women constituted 46.3% of the overall UK workforce in 2012, and nearly 74% of part-time workers,18 the conclusions are that more actions are required to address the problem of gender disparity within architecture. This is despite the ongoing work of Women in Architecture and Architects for Change.

Whilst architecture appears to have higher female representation than many of the other construction disciplines,19 some considerably less well represented disciplines such as engineering have bodies, such as the Women’s Engineering Society (WES), that have been highly proactive in promoting careers for women in engineering, science and technology.20 Their current range of initiatives includes career advice, prizes, scholarships, grants, identification of role models, personal narratives by practitioners and students, mentoring, and providing details of employment opportunities. WES has regional clusters and also student groups based in a number of universities. A considerable range of sponsors (at least 26), including the Department of Energy and Climate Change, large corporations such as Airbus, and engineering practices such as Arup, have helped to facilitate initiatives,

A separate organisation, Girl Geek Dinners, set up by Sarah Lamb, offers events including talks and dinners, and general encouragement to women in engineering. Part of her rationale for setting up this organisation was her belief that women in engineering and technology were isolated and, ‘that not all men know how to react to a technical female’.21

Architectural Education 2000–2014

Since the academic year 2000–2001, female representation in architecture schools has grown slowly. Female entry to Part 1 has risen from 36% in 2000 to 45.6% in 2014.22 In comparison, women represented 56.2% of the undergraduate population in the UK in 2012.23 Representation at Part 2 has traditionally trailed Part 1 and entry figures remained relatively static at approximately 35% until 2008, when the figure rose to 36.1%. From there on, a perceivable increase has taken place. The 2014 Part 2 entry figures indicate that women constituted 43% of the intake. The percentages of women successfully completing Part 1 and 2 appears to be close to the entry representation and in some instances is slightly higher. Between the academic years 2006–7 and 2013–14 the percentage of women passing the final professional examination rose from 32.4% to 38.2%. What has been consistent over the years is that female representation has diminished at each of the stages on the road to qualification. The traditional minimum seven years of training – on average rather longer – may have a greater personal impact on women.

The Interviews

Five women architects, all of whom had left the profession, were interviewed in depth. Their ages ranged from early 30s to early 50s. Two had achieved senior positions, one of whom had reached the position of director before being made redundant during the recession.

Interviewees were asked about their experiences and perceptions of practice, the culture of the profession and also architectural education. We discussed their career histories and paths, what opportunities for advancement they had had, how they had been treated, and whether there were any issues arising from career breaks and caring responsibilities. The role of professional bodies and the nature of media representation of women architects were also discussed.

One aspect that stood out from these interviews was the long hours culture. It was seen as a fundamental concern that resulted in an unhealthy work-life balance and an ineffective, inefficient way of working. In all cases, excessive working hours appeared to be a major factor in decisions to leave the profession. Those women who had children particularly placed priority on effective and sensible timekeeping that worked with their family commitments. But even women without children or other caring responsibilities noted the serious impact of long hours on the wellbeing of all architects, not just women. Most interviewees felt that client expectations drove the tendency to long hours and impossible deadlines but they were unanimous in believing that the long hours culture started at architecture school.

was one respondent’s comment about her experience of architectural education. Another interviewee stated that:

One woman had been ill during her time at architecture school and unable to do ‘all-nighters’. She felt that, because of this, she was treated in a dismissive fashion.

A common theme was male-dominated work environments. Opinions such as, ‘Very few women at the top table in architectural practice’ and, ‘The female voice is not really heard’, were expressed. They commented on the dearth of female role models and felt that more were needed. Most of the interviewees stressed the importance of women architects having a media profile:

Among other things, one respondent felt this reinforces the impression that architecture is a well-paid profession for men. Another commented that, ‘Architects were portrayed as well paid and well valued’. This, she said, was ‘a dream like view, a huge disconnect from reality. The reality is architects are overworked, underpaid and exhausted’.

Some interviewees confirmed that they had been harassed. One cited a case where she had challenged a senior male colleague because of harassment and he had apologised. She had sufficient confidence to address the situation herself but felt that not everyone would feel able to make such a challenge. She wondered how would-be women architects could be better equipped to handle inappropriate behaviour and take action to prevent it. Other interviewees stated that they had not encountered any bullying or harassment, but then went on to describe situations which might have been defined by others as bullying. For instance, one woman said that a retired architect had been appointed to ‘keep an eye on her’ and she had felt intimidated by this.

In relation to contractors and other parties, while displays of nude calendars were mentioned, there was a general opinion that this was silliness rather than significant sexism and it was not considered to be a serious issue. One expressed the opinion that:

Some women confirmed that their redundancy was associated with the 2008 economic downturn, and added that because they were working part-time they were easy targets. Additional workload due to fewer staff further aggravated the issue of work-life balance. One woman noted the significant loss of public sector roles during the recession. These had been a traditional bolt-hole for women with children because of better flexible working policy and job share provision.

The need for networking opportunities and support for returners were cited by some interviewees.

Most of the women had completed their education years ago and so some of their comments on the subject may no longer be so applicable. However, the traditional length and breakdown of architectural education still remains a three-part course with two years practical experience. Several women thought that this was too long. They considered that their courses had failed to prepare them adequately for architectural practice, particularly in relation to business management.

The Bologna agreement may lead to changes in the duration and/or structure of architectural education, which might have an impact on women training to be architects. However, the decisions relating to this are still being thrashed out.24

There were mixed responses to questions about the role of professional bodies. Some thought that RIBA was an important body that did its job well. However, there was an opinion that it had failed to assist women who wanted to return to the profession. There were some concerns about the obligatory 35 hours of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) that all RIBA members are required to undertake to maintain their professional competence. Respondents were critical of the formal RIBA accredited CPD, considering it too focused on product related talks with limited educational worth. One respondent felt that establishing more effective networks of women returners and providing bite-size updates on matters such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) and procurement would be much more valuable.

All the respondents considered that it was imperative that women were better represented by the professional institutes. They also thought that women had an important contribution to make towards the creation of the built environment and that they brought different perspectives and qualities to the profession, particularly regarding social aspects and community and user experience.

Why Women Might Return to Architecture

Interviewees’ recommendations for change included support networks, returner training, structures which offered better work-life balance, flexible working provision, better information provided by RIBA regarding the role of architects, more women-run practices, and more women in senior positions:

What Might make Women Stop Leaving Architecture?

In the intervening years since our first report, it appears that little has changed. The profession remains a predominantly male one, and women’s contribution continues to be overlooked. The long hours culture prevails and is at odds with national patterns of work for women. There is a lack of provision for returners going back into architecture after career breaks. In architectural education, female students are still under-represented. Some of the existing support offered is only available in the capital.

We believe that it is time for a serious review of the profession and identification of actions. The profile of architecture as a career for women must be raised and necessary support frameworks put in place to avoid attrition. The drive for change can be spearheaded by RIBA, but needs to be at national and regional level and undertaken collaboratively with a wider committed group of people. The gendered career pathways instilled at an early age need to be challenged by ensuring the visibility of female architects and their work. The low or non-existent profile of women diminishes the profession and, as stated by one of our interviewees, creates an antediluvian and inappropriate situation. RIBA is well placed to update and offer good practice guidance and initiatives (accompanied by the business case) on flexible working patterns, healthy work-life balance, workplace diversity, inclusive practice, mentoring and networking.

The loss of creative talent of the women who leave ill serves the profession as it fights to retain its influence. Members of other professions are only too ready to step in and take up the roles that were previously the domain of architects. It is essential that the architectural profession is fit for purpose in the 21st century.

Finally it is evident that the outdated working practices and culture also damage men. A paradigm shift to create a more flexible and inclusive working environment would benefit all architects, not just women.