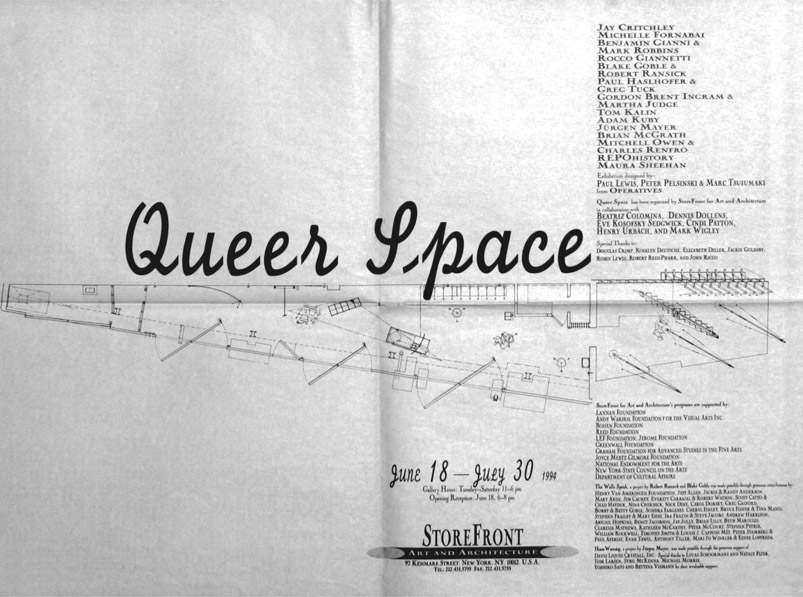

In the fall of 1992, Storefront for Art and Architecture, an alternative gallery in New York City, invited a group, initially made up of Beatriz Colomina, Dennis Dollens, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Elizabeth Diller, to organise an exhibition ‘that would articulate the role of space in questions of sexuality’.1 One year later, the group released an open call for manifestos and proposals, in the form of a ‘Wanted’ personal ad. Half a year after that, the gallery mounted the exhibition, titled Queer Space. The exhibition – often referred to more broadly as the Queer Space project – included 14 installations and documentation of the project’s planning, as well as a modest publication of manifestos.

While ‘multifaceted and ambitious’2 the project was also in many ways incoherent. This incoherence can perhaps be celebrated but only if it is in turn critically scrutinised. The exhibition’s introduction, call for proposals, and curatorial text all resisted any singular definition of ‘queer space’, which allowed for a myriad of responses and avoided over-determining the resulting exhibition. However, this same resistance – which amounted to starting a discussion but declining to ask specific questions – undermined any attempt at a coherent project. In the end, the exhibition lacked a curatorial thesis and failed to create any sustained debate, but the installations and publication of manifestos constitute a discursive site from which to understand the exhibition’s importance as a historical event and object of critical inquiry. Revisiting Queer Space might then reveal its gaps and ellipses while also beginning a new discussion of the complex relationship between spatial politics and sexuality.

A Project in Print

Like every exhibition held at Storefront for Art and Architecture, Queer Space was accompanied by a published newsprint announcing the exhibition, listing the participants, and reproducing curatorial text and individual project manifestos. The four curatorial texts printed on the broadsheet not only delineate the goals and strategies of the Queer Space project but also define the conceptual underpinnings of the endeavour. The project manifestos provide the most consistent record of the installations that constituted the exhibition itself – though they are in fact dramatically inconsistent. This newsprint is the primary source for any material understanding of the exhibition, and a close reading of its texts reveals the challenges of the project as well as its possible antagonisms.

The first text is the ‘Introduction’, written only by Colomina. This brief statement, just two paragraphs long, describes both the origins and development of the project. It also lists the various participants of the discussion group, in which the final group of organisers included Colomina, Dollens, Sedgwick, Henry Urbach, and Mark Wigley. In her description of the project meetings, Colomina is quick to characterise the exhibition’s focus as unwieldy, taking shape ‘even before the first meeting,’ as if out of their control.3 She goes on to describe the inability of the group to determine what the project should even have resulted in, writing that ‘the very idea of an exhibition was repeatedly contested’.4 Instead, the group seemed to be in constant search of purpose, producing manifestos that were continuously written, edited, rewritten, and disseminated by fax machine. After providing a laundry list of possible alternatives, the decision to cast an open call for manifestos and projects is described almost as a last-ditch effort to produce something, anything; the initial goal of the project unrecognisable as it ended up ‘not so much an exhibition as a forum for debate’.5 Alongside this introduction is a reproduction of a fax: a manifesto written by Sedgwick, a trace of dialogue and debate, which would, for better or worse, define the project.

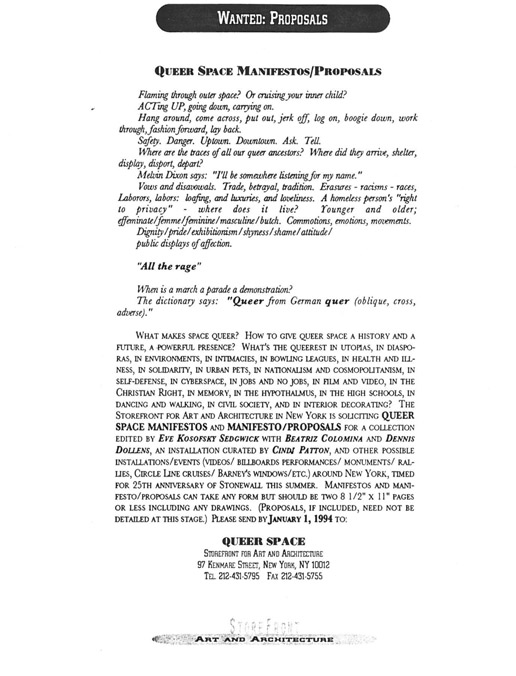

The second text is the call for proposals, authored solely by Sedgwick. In this text, Sedgwick provides a context for the proposals, and by extension the exhibition, situating this endeavour in dialogue with the emergence of queer theory as well as within the rhetoric of queer culture. Through her use of gay colloquialisms (‘Flaming through outer space? Or cruising your inner child?’6), and references to various political groups and movements, Sedgwick firmly grounded the call within an already existing discourse, while careful not to explicitly define ‘queer’ as necessarily tied to sexual identity. Space is described in terms that are as open as they are clear, outlined as a series of places both physical (high schools) and mental (nationalism). Even the format of the call, styled as a personal ad, borrows a form that, while not exclusively queer, certainly nods to the alternative modes of communication and dissemination used within queer communities. At the same time, this specific reference to the circulation of an ad offers a specific mode in which space might be conceptualised. While it might be simplistic to assume that because the exhibition was organised in the early 1990s it was both aware of and responsive to the social and political tensions around sexuality, the call for proposals shows that even if it was not the primary motivator of the project, the manifestos and proposals, and thus the exhibition, respond to a clear set of emergent social and political issues.

The third text, ‘Something About Space is Queer’, is both the only text to define any sort of specific curatorial voice for the exhibition as well as the only writing produced collaboratively by the multiple organisers. The outline of the exhibition begins with the initial premise that ‘all space is queer’.7 It was from this notion that this group hoped to present works that would address ‘being queer in space’ as well as challenge existing views of ‘queered space and of queers occupying, writing and designing both literal and literary space’.8

This lone curatorial text highlights not only the unfocused aim of the exhibition but also the lack of proper terms for the exhibition as it grapples with both the theoretical and social hang-ups of the language necessary to establish a discourse of queer space. Thus, this exhibition’s primary focus was in many ways less on queer space itself and more an attempt to understand the terms ‘queer’ and ‘space’.

The Queer Space project called existing definitions of these terms into question, as well as any relationship between them. Not taking for granted the meaning of either term, the organisers asserted that ‘queer’ could refer to a general oddness as much as it does sexual identities, and that ‘space’ could be physical, literary or discursive. But while allegedly trying to question these stereotypical definitions, they simultaneously reinforce them as the point at which a conversation about queer space should begin. By relying on these stereotypes, this text failed to position the exhibition in relation to other important concerns that should have been factored into the conversation, such as issues of sexism, classism or racism, which were left completely unaddressed by the organisers.

An Exhibition in Context

It is important to situate the Queer Space project within the context of other projects that addressed the relationship of architecture, gender and sexuality. Perhaps the most important event against which to examine Queer Space is the conference and publication Sexuality and Space. In 1990, Colomina organised the two-day conference at which 12 scholars asked: ‘How is the question of space already inscribed in the question of sexuality?’9 Two years later, the papers presented at the conference were published as the first book in the Princeton Papers on Architecture series. On the heels of this publication, the invitation from Storefront for Art and Architecture to organise an exhibition addressing sexuality could easily have been a way to continue the conversations and questions from Sexuality and Space.

The Queer Space project precisely offered the opportunity to expand this discourse, shifting the focus to questions of sexuality. And more than that, its intentions as an investigation specifically into queer sexuality had the potential to open up a conversation that engaged contemporaneous social and political issues while responding to an established discourse. But the multiplicity and indeterminacy of this project was quickly characterised as unruly rather than embraced as a way of working towards an open-ended understanding of queer space.

When Colomina describes Queer Space as an exhibition ‘that would articulate the role of space in questions of sexuality’, she employs language that strongly resembles that of her earlier project, establishing a relationship between the two. But in the various texts surrounding the Queer Space exhibition, there is an apparent lack of language to address sexuality and space in terms of queer sexuality. Therefore, this exhibition’s goal of defining its own terms, ‘queer’ and ‘space’, is a necessary step in potentially expanding the conceptual foundation laid by the earlier Sexuality and Space.

Because queer theory was very much an emerging field of academic study, one might sympathise with the difficulty of finding established foundations upon which this exhibition could ground a discussion of queer space. But the fourth text on the newsprint, ‘Christmas Effects’, shows that the exhibition organisers did in fact have the material to position the exhibition within an existing dialogue on queer sexuality. This text was excerpted from Sedgwick’s 1993 book, Tendencies, the first title published in the Series Q by Duke University Press, which provided a queer focus within gay and lesbian studies, placing queer theory within an existing discourse on sexuality. In ‘Christmas Effects’, Sedgwick does not provide a static definition of the term queer, but lends it a sense of flexibility, deconstructing the term while managing to maintain its coherence. She proposes that while ‘queer’, even in her own use, leans towards the destabilisation of the interdependence of categorical understandings of sex, gender and sexuality, the term is only further enriched by increasing its ‘fractal intricacies’. By conceptualising ‘queer’ as an operation of destabilisation, it becomes a term that signifies its meaning only when linked to an individual subject. While a reliance on Sedgwick’s definition or an unquestioning support of it would have been equally problematic, it is a flaw of the exhibition that it so disparagingly characterised any attempt to define its terms as both impossible and undesirable. But again, any attempt to describe the motivations for Queer Space only reinforced that the goal of this project was not to generate a specific argument or thesis, rather a provocation: ‘Our concern was to open the question of queer space up rather than pin it down aesthetically or conceptually.’10 Sifting through all the submitted manifestos and proposals affirms that there has been little learned about ‘queer’, ‘space’, or their relationship, let alone what a definition of queer space itself might be. When Colomina asserts that ‘queerness is not simply a property of certain subjects or certain spaces or certain relationships between them’, that same desire not to pin down ‘queer space’ as a singular idea simultaneously makes it impossible to address critically.11

A Set of Manifestos

The 14 individual projects and their respective manifestos each presented potential ways to define queer space, even if the exhibition itself refused to do so. The projects all took on the task of understanding the terms of queer space while also maintaining an interest in both the queer subject and queer uses of space. These projects offered various instances of how queer space could manifest in moments, experiences or individual identities, which need not come together to present any single version of queer space. Instead, it is their multiplicity that points to the possibility of a discourse on queer space, one hinged upon a diversity of meanings.

Many of the manifestos, such as Jurgen Mayer’s Housewarming, provide both a description of the project – ‘Applications of green-to-yellow temperature sensitive coatings to contact elements in the architectural environment. YOU CAN TOUCH ME’ – paired with a conceptual framework; in this case, the use of a Hallmark Cards phrase: ‘Our new home…/All it needs is the warmth of friends.’ Other projects such as Michelle Fornabai’s Death Drive, and Maura Sheehan’s The Cross-Dressed Dumpster, focus more heavily on positioning the conceptual underpinnings of their project, and only allude to the project’s physical presence as an installation in the exhibition.

But many of the project manifestos include only information directly drawn from their project, such as the manifesto of Charles Renfro and Mitchell Owen, which reproduces two narratives from a collection of ‘A Remapping of New York’. While these descriptive manifestos help to understand what was actually installed and presented at the exhibition itself – which is especially useful for understanding projects that were realised beyond the gallery, such as REPOhistory’s project in which queer history signs were installed around New York City. This project created landmarks and called attention to often-unremembered historical events.

Because these manifestos all describe different aspects of their projects, it is difficult to use them as a way to discuss the exhibition installations. Nevertheless, they remain the primary documentary remains of the exhibition. Focusing on these manifestos is important to highlight the relationship between the use of language and the installations within the exhibition. As the exhibition itself does not attempt to present a specific thesis, each of the installations becomes an accumulation of potential theses. Since one of the primary concerns outlined by the exhibition was to uncover a language, a set of tools, with which a discourse between space and sexuality might be forged, the manifestos are especially important contributions. The installations are then not only specific manifestations or representations of queer space, but also provide their own terms and language that can contribute to a discourse on queer space.

An Open Conclusion

One of the largest struggles encountered by the Queer Space project was an inability to find institutional support. In her introduction, Colomina writes, ‘We are proud to announce that we were rejected by every institution that we applied to for financial support.’12 In Storefront for Art and Architecture’s archive, folders of letters, faxes and grant applications detail the confusion about such a project. There seems to have been a lack of understanding about the role of architecture in a conversation that eluded any discussion of buildings. But the project did assert an academic interest in understanding the relationship between sexuality and space, which was substantiated by the many responses to the call for proposals.

Because the project was so concerned with understanding the theoretical stakes in a discussion of queer space, the physical exhibition itself became a secondary concern. The curatorial focus of the exhibition was on the language and terms of queer space rather than the installations. However, despite claiming that such a project could only begin an urgently necessary and sustained conversation, there has been little continued discussion surrounding this initial endeavour in the years since the exhibition.

The most valuable contribution that the Queer Space exhibition provided was to acknowledge and, to some extent, provoke questions that clearly need to keep being asked about sexuality and space: ‘The built environment can no longer be exempted from a sustained interrogation on these issues.’13 Over 20 years later, this declaration still stands. By remembering the Queer Space exhibition, and keeping in mind everything that it did and did not accomplish, we can continue, through essays, manifestos, and installations, the conversation about queer space.