Chapter 1

Introduction to Accounting

This chapter introduces accounting and its functions and provides a short history of accounting, highlighting the roles of both financial and management accounting, and the interaction between both. It also describes the recent developments that have changed the roles of accountants and non-financial managers in relation to the use of financial information. The chapter concludes with a brief critical perspective on accounting.

Accounting, accountability and the account

Businesses exist to provide goods or services to customers in exchange for a financial reward. Public-sector and not-for-profit organizations also provide services, although their funding may be a mix of income from service provision, government funding and charitable donations. While this book is primarily concerned with profit-oriented businesses, most of the principles are equally applicable to the public and not-for-profit sectors. Business is not about accounting. It is about markets, people and operations (the delivery of products or services), although accounting is implicated in all of these decisions because it is the financial representation of business activity.

Although it is quite a dated definition, the American Accounting Association defined accounting in 1966 as:

The process of identifying, measuring, and communicating economic information to permit informed judgements and decisions by users of the information.

This is an important definition because:

- it recognizes that accounting is a process: that process is concerned with capturing business events, recording their financial effect, summarizing and reporting the result of those effects, and interpreting those results (we cover this in Chapter 3);

- it is concerned with economic information: while this is predominantly financial, it also allows for non-financial information (which is explained in Chapter 4);

- its purpose is to support ‘informed judgements and decisions’ by users: this emphasizes the decision usefulness of accounting information and the broad spectrum of ‘users’ of that information. While the primary concern of this book is the use of accounting information for decision making, the book takes a broad stakeholder perspective that users of accounting information include all those who may have an interest in the survival, profitability and growth of a business: shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, financiers, government and society as a whole.

The notion of accounting for a narrow (shareholders and financiers) or a broad (societal) group of users is an important philosophical debate to which we will return throughout this book. This debate derives from questions of accountability: to whom is the business accountable? For what is the business accountable? And what is the role of accounting in that accountability?

Boland and Schultze (1996) defined accountability as:

The capacity and willingness to give explanations for conduct, stating how one has discharged one’s responsibilities, an explaining of conduct with a credible story of what happened, and a calculation and balancing of competing obligations, including moral ones (p. 62).

Hoskin (1996) suggested that accountability is:

more total and insistent . . . [it] ranges more freely over space and time, focusing as much on future potential as past accomplishment (p. 265).

Boland and Schultze argued that accountability entails both a narration of what transpired and a reckoning of money, while Hoskin focused on the future as well as the past. There are many definitions of accountability, but they all derive from the original meanings of the word account.

Accounting is a collection of systems and processes used to record, report and interpret business transactions. Accounting provides an account – an explanation or report in financial terms – about the transactions of an organization. Exhibit 1.1 provides a number of different definitions for the word ‘account’.

An account enables managers to satisfy the stakeholders in the organization that they have acted in the best interests of stakeholders rather than themselves. This is the notion of accountability to others, a result of the stewardship function of managers by which accounting provides the ability for managers to show that they have been responsible in their use of resources provided by various stakeholders. Stewardship is an important concept because in all but very small businesses, the owners of businesses are not the same as the managers. This separation of ownership from control makes accounting particularly influential due to the emphasis given to increasing shareholder wealth (or shareholder value) as well as the broader stakeholder perspective that organizations need to contribute to the sustainability of natural resources and the environment (we cover corporate social responsibility in Chapter 7).

- A narrative or record of events.

- A reason given for a particular action or event.

- A report relating to one’s conduct.

- To furnish a reckoning (to someone) of money received and paid out.

- To make satisfactory amends.

- To give satisfactory reasons or an explanation for actions.

Introducing the functions of accounting

Accounting is traditionally seen as fulfilling three functions:

- Scorekeeping: capturing, recording, summarizing and reporting financial performance.

- Attention-directing: drawing attention to, and assisting in the interpretation of, business performance, particularly in terms of the trend over time, and the comparison between actual and planned, or a benchmark measure of performance.

- Problem-solving: identifying the best choice from a range of alternative actions.

In this book, we acknowledge the role of the scorekeeping function in Chapters 6 through 8. We are not concerned with how investors make decisions about their investments in companies, so we emphasize attention directing and problem solving as taking place through three inter-related functions, all part of the role of non-financial (marketing, operations, human resources, etc.) as well as financial managers:

- Planning: establishing goals and strategies to achieve those goals.

- Decision making: using financial (and non-financial performance) information to make decisions consistent with those goals and strategies.

- Control: using financial (and non-financial) information to improve performance over time, relative to what was planned, or using the information to modify the plan itself.

Planning, decision making and control are particularly relevant as increasingly businesses have been decentralized into many business units, where much of the planning, decision making and control is focused.

Accountability results in the production of financial statements, primarily for those interested parties who are external to the business. This function is called financial accounting. Managers need financial and non-financial information to develop and implement strategy by planning for the future (budgeting); making decisions about products, services, prices and what costs to incur (decision making using cost information) and ensuring that plans are put into action and are achieved (control). This function is called management accounting.

A short history of accounting

The history of accounting is intertwined with the development of trade between tribes and there are records of commercial transactions on stone tablets dating back to 3600 BC (Stone, 1969). The early accountants were ‘scribes’ who also practised law. Stone (1969) noted:

In ancient Egypt in the pharaoh’s central finance department . . . scribes prepared records of receipts and disbursements of silver, corn and other commodities. One recorded on papyrus the amount brought to the warehouse and another checked the emptying of the containers on the roof as it was poured into the storage building. Audit was performed by a third scribe who compared these two records (p. 284).

However, accounting as we know it today began in the fourteenth century in the Italian city-states of Florence, Genoa and Venice as a result of the growth of maritime trade and banking institutions. Ship-owners used some form of accounting to hold the ships’ captains accountable for the profits derived from trading the products they exported and imported. The importance of maritime trade led to the first bank with customer facilities opening in Venice in 1149. Trade enabled the movement of ideas between countries and the Lombards, Italian merchants, established themselves as moneylenders in England at the end of the twelfth century.

Balance sheets were evident from around 1400 and the Medici family (who were Lombards) had accounting records of ‘cloth manufactured and sold’. The first treatise on accounting (although it was contained within a book on mathematics) was the work of a monk, Luca Pacioli, in 1494. The first professional accounting body was formed in Venice in 1581.

Much of the language of accounting is derived from Latin roots. ‘Debtor’ comes from the Latin debitum, something that is owed; ‘assets’ from the Latin ad + satis, to enough, i.e. to pay obligations; ‘liability’ from ligare, to bind; ‘capital’ from caput, a head (of wealth). Even ‘account’ derives initially from the Latin computare, to count, while ‘profit’ comes from profectus, advance or progress. ‘Sterling’ and ‘shilling’ came from the Italian sterlino and scellino, while the pre-decimal currency abbreviation ‘LSD’ (pounds, shillings and pence) stood for lire, soldi, denarii.

Little changed in terms of accounting until the Industrial Revolution. Chandler (1990) traced the development of the modern industrial enterprise from its agricultural and commercial roots in the last half of the nineteenth century. By 1870, the leading industrial nations – the USA, Great Britain and Germany – accounted for two-thirds of the world’s industrial output. One of the consequences of growth was the shift from home-based work to factory-based work and the separation of ownership from management. Although the corporation, as distinct from its owners, had been in existence in Britain since 1650, the separation of ownership and control was enabled by the first British Companies Act, which formalized the law in relation to ‘joint stock companies’ and introduced the limited liability of shareholders during the 1850s. The London Stock Exchange had been formed earlier in 1773. These changes raised the importance of accounting and accountability.

The era of mass production began in the early twentieth century with Henry Ford’s assembly line. Organizations grew larger and this led to the creation of new organizational forms. Based on an extensive historical analysis, Chandler (1962) found that in large firms strategic growth and diversification led to the creation of decentralized, multidivisional corporations. Chandler’s work thus emphasized structure following strategy. Chandler studied examples like General Motors, where remotely located managers made decisions on behalf of absent owners and central head office functions.

Ansoff (1988) emphasized that success in the first 30 years of the mass-production era went to firms that had the lowest prices. However, in the 1930s General Motors ‘triggered a shift from production to a market focus’ (p. 11).

In large firms such as General Motors, budgets were developed to coordinate diverse activities. In the first decades of the twentieth century, the DuPont chemicals company developed a model to measure the return on investment (ROI). ROI (see Chapters 7, 14 and 15) was used to make capital investment decisions and to evaluate the performance of business units, including the accountability of managers to use capital efficiently.

The role of financial accounting

Financial accounting is the recording of financial transactions, aimed principally at reporting performance to those outside the organization, with a primary focus on shareholders. In countries like the UK, USA, Canada and Australia, companies legislation usually dictates that directors of companies are required to report the financial performance of the companies they run to shareholders. They do so through an Annual Report to shareholders, which comprises four financial statements: the Statement of Comprehensive Income (or Income Statement, and in old terminology the Profit and Loss Account); the Statement of Financial Position (or Balance Sheet); the Statement of Changes in Equity; and the Statement of Cash Flows (these are the topics of Chapters 6 and 7).

These financial statements are regulated by legislation and by accounting standards, and subject to independent audit in order to provide comparisons between different companies (Chapter 6 explains this in detail). However, the information they provide is of limited decision usefulness for managers because the financial information is produced only once per year, is highly aggregated and provides no comparison to target (although the financial statements do provide a prior year comparison).

While financial accounting is extremely important for investors, it is also important for managers for two reasons. First, many managerial decisions, whether they relate to planning, decision making or control involve decisions that will ultimately be reported in financial statements and affect shareholder reaction in stock markets. Hence the decisions of managers are influenced by how those decisions will be presented to (and interpreted by) users of financial statements. Second, the accounting system that produces financial reports is the same system that managers use for planning, decision making and control. This financial accounting information is supplemented by non-financial performance measures and by more detail and analysis derived from outside the financial accounting system. However, financial accounting still provides the foundation on which managers plan, make decisions and exercise managerial control. As a result of these two reasons, managers need to understand financial accounting in order to take full advantage of the range of management accounting techniques that are available. We explore this in far more detail in Chapters 2, 3, 6 and 7.

The role of management accounting

The advent of automated production following the Industrial Revolution increased the size and complexity of production processes, which employed more people and required larger sums of capital to finance machinery. Accounting historians suggest that the increase in the number of limited companies that led to the separation of ownership from control caused an increase in attention to what was called ‘cost accounting’ (the forerunner of ‘management accounting’) in order to determine the cost of products and exercise control by absent owners over their managers. Reflecting this emergence, the earlier title of management accountants was cost or works accountants. Typically situated in factories, cost or works accountants tended to understand the business at a technical level and were able to advise non-financial managers in relation to operational decisions. Cost accounting was concerned with determining the cost of an object, whether a product, an activity, a division of the organization or market segment. The first book on cost accounting is believed to be Garcke and Fell’s Factory Accounts, which was published in 1897.

Historians, such as Chandler (1990), have argued that the new corporate structures that were developed in the twentieth century – multidivisional organizations, conglomerates and multinationals – placed increased demands on accounting. These demands included divisional performance evaluation and budgeting. It has also been suggested that developments in cost accounting were driven by government demands for cost information during both world wars. It appears that ‘management accounting’ became a term used only after World War II.

In their acclaimed book Relevance Lost, Johnson and Kaplan (1987) traced the development of management accounting from its origins in the Industrial Revolution supporting process-type industries such as textile and steel conversion, transportation and distribution. These systems were concerned with evaluating the efficiency of internal processes, rather than measuring organizational profitability. Financial reports were produced using a separate transactions-based system that reported financial performance. Johnson and Kaplan (1987) argued that ‘virtually all management accounting practices used today had been developed by 1925’ (p. 12).

Calculating the cost of different products was unnecessary because the product range was homogeneous, but Johnson and Kaplan (1987) described how the early manufacturing firms attempted to improve performance through economies of scale by increasing the volume of output in order to lower unit costs. This led to a concern with measuring the efficiency of the production process. Over time, the product range of businesses expanded to meet the demands of the market and so businesses sought economies of scope through producing two or more products in a single facility. This led to the need for better information about how the mix of products could improve total profits.

Johnson and Kaplan (1987) described how

a management accounting system must provide timely and accurate information to facilitate efforts to control costs, to measure and improve productivity, and to devise improved production processes. The management accounting system must also report accurate product costs so that pricing decisions, introduction of new products, abandonment of obsolete products, and response to rival products can be made (p. 4).

The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants’ definition of the core activities of management accounting includes:

- participation in the planning process at both strategic and operational levels, involving the establishment of policies and the formulation of budgets;

- the initiation and provision of guidance for management decisions, involving the generation, analysis, presentation and interpretation of relevant information;

- contributing to the monitoring and control of performance through the provision of reports including comparisons of actual with budgeted performance, and their analysis and interpretation.

One of the earliest writers on management accounting described ‘different costs for different purposes’ (Clark, 1923). This theme was developed by one of the earliest texts on management accounting (Vatter, 1950). Vatter distinguished the information needs of managers from those of external shareholders and emphasized that it was preferable to get less precise data to managers quickly than complete information too late to influence decision making. Johnson and Kaplan (1987) commented that organizations

with access to far more computational power . . . rarely distinguish between information needed promptly for managerial control and information provided periodically for summary financial statements (p. 161).

They argued that the developments in accounting theory in the first decades of the twentieth century came about by academics who

emphasized simple decision-making models in highly simplified firms – those producing one or only a few products, usually in a one stage production process. The academics developed their ideas by logic and deductive reasoning. They did not attempt to study the problems actually faced by managers of organizations producing hundreds or thousands of products in complex production processes (p. 175).

They concluded:

Not surprisingly, in this situation actual management accounting systems provided few benefits to organizations. In some instances, the information reported by existing management accounting systems not only inhibited good decision-making by managers, it might actually have encouraged bad decisions (p. 177).

Johnson and Kaplan (1987) described how the global competition that has taken place since the 1980s has left management accounting behind in terms of its decision usefulness. Developments such as total quality management, just-in-time inventory, computer-integrated manufacturing, shorter product life cycles (see Chapters 11 and 18) and the decline of manufacturing and rise of service industries have led to the need for ‘accurate knowledge of product costs, excellent cost control, and coherent performance measurement’ (p. 220). And ‘the challenge for today’s competitive environment is to develop new and more flexible approaches to the design of effective cost accounting, management control, and performance measurement systems’ (p. 224).

There have been many changes since Relevance Lost was published in 1987. However, most of those changes have been in financial accounting. The next section describes relatively recent developments in accounting practice.

Recent developments in accounting

Compared to 20 years ago, financial accounting has gained in importance relative to management accounting. This is due to two reasons. First, the globalization of financial markets and the ability of investors to invest in stock markets around the world increased the need for financial statements that were comparable across different countries, rather than being based on local legislation and standards. The development of the UK-led International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) has resulted in almost all significant economies adopting a single set of reporting standards that enables investors to compare company performance across national boundaries. The only significant economy not to have yet adopted IFRS is the USA which still relies on Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). The topic of financial reporting standards is discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

The second reason has been the large corporate failures that have raised questions about why financial statements have not provided early warning signals about the risk of failure. The size of some of these failures, with Enron and WorldCom as notable examples, and the increasing complexity of business transactions (some of which have been designed to improve the perception of reported performance, rather than the underlying reality) have led to a continual change in accounting standards in trying to improve their usefulness to investors.

The advent of IFRS, corporate failures and transactional complexity has led to an emphasis (and this author would argue an undue overemphasis) on reporting past – and typically short-term – performance designed to satisfy stock market investors, rather than improving the value-added capability of organizations to be successful in the longer term. While there have been significant management accounting developments in the last 20 years, these have tended to be overshadowed by financial reporting. We will return to these issues throughout this book. Of particular importance is recognizing that financial accounting is essential in reporting business performance and demonstrating accountability to investors, but management accounting comprises the set of tools and techniques that will help to improve and sustain business performance.

Partly as a result of the stimulus of Relevance Lost (Johnson and Kaplan, 1987) but also as a consequence of rapidly changing business conditions, management accounting has moved beyond its traditional concern with a narrow range of numbers to incorporate wider issues of performance measurement and management. Management accounting is now concerned, to greater or lesser degrees in different organizations, with:

- value-based management;

- non-financial performance measurement;

- a focus on horizontal business processes or activities, rather than hierarchical reporting based on individual managerial responsibilities;

- quality management and environmental management;

- strategic issues beyond the boundaries of the organization and the annual reporting cycle; and

- lean methods of producing goods and services.

Value-based management is more fully described in Chapter 2, but it is in brief a concern with improving the value of the business to its shareholders. A fundamental role of non-financial managers is to make marketing, operational, human resource and investment decisions that contribute to increasing the value of the business. Accounting provides the information base to assist in planning, decision making and control.

The limitations of accounting information, particularly as a lagging indicator of performance, have led to an increasing emphasis on non-financial performance measures, which are described more fully in Chapter 4. Non-financial measures are a major concern of both accountants and non-financial managers, as they tend to be leading indicators of the financial performance that will be reported at some future time.

Activity-based management is an approach that emphasizes the underlying business processes that cut across the traditional organizational structure but are essential to produce goods and services. This approach reflects the need to identify the drivers or causes of those activities in order to be able to plan and control costs more effectively. Activity-based approaches are introduced throughout Part III.

Improving the quality of products and services is also a major concern, since advances in production technology and the need to improve performance by reducing waste have led to management tools such as total quality management (TQM), and continuous improvement processes such as Six Sigma and the Business Excellence model. Greater attention to environmental issues as a result of climate change has also led companies to better understand the short-term and long-term consequences of inefficient energy usage and environmental pollution. Managers can no longer ignore these issues and accounting has a role to play in measuring and reporting quality and environmental costs (see Chapter 11).

Strategic management accounting, which is described more fully in Chapter 18, is an attempt to shift the perceptions of accountants and non-financial managers from inward-looking to outward-looking, recognizing the need to look beyond the business to the whole supply chain with suppliers and customers, and beyond the current accounting period to product life cycles, and to seek ways of achieving and maintaining competitive advantage.

Lean accounting is a consequence of lean manufacturing, itself a development of the just in time philosophy which focuses on the elimination of inventory. Lean approaches emphasize reducing all waste, and its application to accounting is to identify and eliminate wasteful accounting practices which contribute little to management decision making.

In addition to these changes has been the rapid improvement in information and communications technologies. Computerization has eliminated many routine accounting processes (which were more correctly book-keeping processes) and has expanded information systems beyond accounting to enterprise resource planning systems (ERPS, see Chapter 9) which integrate marketing, purchasing, production, distribution and human resources with accounting. The ready availability of information systems has also enabled detailed financial reports to be available for non-financial managers soon after the end of each accounting period.

These changes have had two impacts: (i) to change the role of accountants and (ii) to change the role of non-financial managers. Computerization has taken (especially management) accountants away from their ‘bean counter’ image to a role where they are more active participants in formulating and implementing business strategy, and act more as business consultants and advisers to management, providing information and advice that support improving business performance. These changes have also increased the responsibility of non-financial managers from their technical areas of expertise. Most non-financial managers now have responsibility in setting budgets and meeting financial targets. This means that non-financial managers need an increased understanding of accounting to fulfil their accountability to higher levels of management.

The relationship between financial accounting and management accounting

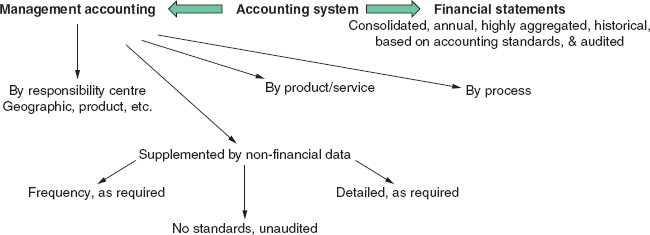

Financial accounting is focused on the needs of external users and demonstrates accountability to shareholders under the stewardship principle. Financial statements have to comply with accounting standards (see Chapter 6) and are subject to audit. They are produced annually, are highly aggregated using historical figures, and provide only a comparison to the prior year. There is a common form of presentation of the Income Statement, Statement of Financial Position and Statement of Cash Flows that applies to all companies.

Management accounting meets the needs of internal users (directors and managers) for planning, decision making and control purposes. They are not subject to audit or accounting standards so organizations can present the information that is relevant to the needs of their business. Management accounting reports typically are produced more frequently (e.g. monthly) and are disaggregated to business unit level with more detail, often supplemented by non-financial information (see Chapter 4) with comparison to budget targets.

Both forms of accounting are important and useful for managers. Figure 1.1 shows the relationship between the accounting system from which is derived both financial statements and management accounting information. However, the inter-relationship goes further than in the use of a common accounting system. The needs of shareholders drive many decisions about using management accounting information, and consequently the planning, decision-making and control activities carried out by managers has an unavoidable impact on reported financial information. Therefore, the decisions that are made by managers in organizations need to integrate the day-to-day operational choices from the result of those choices as they impact on financial statements.

Figure 1.1 The accounting system, financial statements and management accounting.

Finally, financial accounting is largely the domain of qualified accountants, as it is a specialist activity requiring a great deal of knowledge and skill. By contrast, management accounting information is far more routinely in the domain of line managers with various functional roles, who cannot avoid budgetary pressures and the need to control the costs and profitability of the products and services for which they are responsible.

In the USA virtually no-one now calls him or herself a ‘management accountant’. Management accounting knowledge is now incorporated into a variety of financial and increasingly non-financial positions. The title ‘management accountant’ is far more prevalent in the UK where it has been institutionalized by the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA). In Continental Europe the specific terminology of management accountant has never existed and ‘controller’ is a more common title (Hopwood, 2008).

Many non-financial roles now incorporate much of the roles carried out by management accountants. This is particularly so for managers with engineering or technical backgrounds who as line managers have considerable financial autonomy, including responsibility for budgets, cost control, pricing and proposing new capital expenditure. This has been a considerable change in the role of non-financial managers and is why such managers increasingly need a strong financial understanding to complement their technical or operational skills:

Forms of economic calculation now extend into marketing, operations, strategy, and even human resource management, increasingly being prevalent throughout the entire organization as economic considerations have become ever more important. Reflecting increasing pressures from the capital markets, the international intensification of competition and a more general cultural shift toward concerns with economic and monetary considerations, economic calculation now is relevant for most of the organization and its knowledge base is accordingly one that is associated with a much wider variety of occupational positions. Indeed we are now seeing much more of a mixing of economic and non-economic forms of information and control (Hopwood, 2008, p. 10).

A critical perspective

Although the concepts and assumptions underlying accounting are yet to be introduced, having begun this book with an introduction to accounting history, it is worthwhile introducing here a contrasting viewpoint. While this viewpoint is one that may not be accepted by many practising managers, it is worth being aware of the role that accounting plays in the capitalist economic system in which we live and work.

The Marxist historian Hobsbawm (1962) argued that the cotton industry once dominated the UK economy, and this resulted in a shift from domestic production to factory production. Sales increased but profits shrank, so labour (which was three times the cost of materials) was replaced by mechanization during the Industrial Revolution.

Entrepreneurs purchased small items of machinery and growth was largely financed by borrowings. The Industrial Revolution produced ‘such vast quantities and at such rapidly diminishing cost, as to be no longer dependent on existing demand, but to create its own market’ (Hobsbawm, 1962, p. 32).

Advances in mass production followed the development of the assembly line, and were supported by the ease of transportation by rail and sea, and communications through the electric telegraph. At the same time, agriculture diminished in importance. Due to the appetite of the railways for iron and steel, coal, heavy machinery, labour and capital investment, ‘the comfortable and rich classes accumulated income so fast and in such vast quantities as to exceed all available possibilities of spending and investment’ (Hobsbawm, 1962, p. 45).

While the rich accumulated profits, labour was exploited with wages at subsistence levels. Labour had to learn how to work, unlike agriculture or craft industries, in a manner suited to industry, and the result was a draconian master–servant relationship. In the 1840s a depression led to unemployment and high food prices, and 1848 saw the rise of the labouring poor in European cities, who threatened both the weak and obsolete regimes and the rich.

This resulted in a clash between the political (French) and industrial (British) revolutions, the ‘triumph of bourgeois-liberal capitalism’ and the domination of the globe by a few Western regimes, especially the British in the mid-nineteenth century, which became a ‘world hegemony’ (Hobsbawm, 1962). These concepts of industrial production and exploitation of labour were exported to developing countries in the centuries before the twentieth, through the process of British colonialism, and hence the ‘British’ capitalist system was exported throughout the world, not least with the support of a colonial expansionist Empire that lent large sums of money in return for countries’ adoption of the British system. Similar approaches were taken by other European countries as they colonized countries in the African continent and in South-East Asia.

This ‘global triumph’ of capitalism in the 1850s (Hobsbawm, 1975) was a consequence of the combination of cheap capital and rising prices. Stability and prosperity overtook political questions about the legitimacy of existing dynasties and technology cheapened manufactured products. There was high demand but the cost of living did not fall, so labour became dominated by the interests of the new owners of the means of production. ‘Economic liberalism’ became the recipe for economic growth as the market ruled labour and helped national (and especially British) economic expansion. Industrialization made wealth and industrial capacity decisive in international power, especially in the USA, Japan and Germany. National colonialism, it can be argued, has been superseded by a system of colonialism by multinational corporations, largely based in the USA, and to a lesser extent by British and European companies.

Armstrong (1987) traced the historical factors behind the comparative pre-eminence of accountants in British management hierarchies (in relation to other professions) and the emphasis on financial control. He concluded that accounting controls were installed by accountants as a result of their power base in global capital markets, which was achieved through their role in the allocation of the profit surplus to shareholders. Armstrong argued that mergers led to control problems that were tackled by

American management consultants who tended to recommend the multidivisional form of organization . . . [which] entirely divorce headquarters management from operations. Functional departments and their managers are subjected to a battery of financial indicators and budgetary controls . . . [and] a subordination of operational to financial decision-making and a major influx of accountants into senior management positions (p. 433).

A different reading of history is designed to do more than raise readers’ awareness that accounting is not a neutral tool, objectively reporting performance. Accounting is intimately bound up with reinforcing a capitalist system, and privileging shareholders over other stakeholders. This raises a significant question: whether accounting should only be concerned with maximizing short-term profits for current shareholders, or whether it should be more concerned with longer term performance to satisfy a broader range of stakeholders. This implies notions of corporate social responsibility, sustainability for future generations and a consideration of ethics. Roberts (1996) suggested that organizational accounting embodies the separation of instrumental and moral consequences, which is questionable. He argued:

The mystification of accounting information helps to fix, elevate and then impose upon others its own particular instrumental interests, without regard to the wider social and environmental consequences of the pursuit of such interests. Accounting thus serves as a vehicle whereby others are called to account, while the interests it embodies escape such accountability (p. 59).

This is a more critical perspective than that associated with the traditional notion of accounting as a report to shareholders and managers. We will revisit the critical perspective throughout this book.

Conclusion

This chapter introduces the notion of accountability and the function of accounting. It identifies the different roles played by financial accounting and management accounting, and the interaction between those roles. A short history of accounting and a summary of recent developments in accounting are supplemented by a critical perspective on the historically derived position of accounting in Western economies. This chapter provides a broad introduction to many concepts that will be developed further throughout this book.

While this book is designed to help non-financial managers understand the tools and techniques of accounting, it is also intended to make readers think critically about the role and limitations of accounting. One intention is to reinforce to readers that:

accounting information provides a window through which the real activities of the organization may be monitored, but it should be noted also that other windows are used that do not rely upon accounting information (Otley and Berry,1994, p. 46).

References

American Accounting Association (1996). A Statement of Basic Accounting Theory. Sarasota, FL: American Accounting Association.

Ansoff, H. I. (1988). The New Corporate Strategy. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Armstrong, P. (1987). The rise of accounting controls in British capitalist enterprises. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 12(5), 415–36.

Boland, R. J. and Schultze, U. (1996). Narrating accountability: cognition and the production of the accountable self. In R. Munro and J. Mouritsen (Eds), Accountability: Power, Ethos and the Technologies of Managing, London: International Thomson Business Press.

Chandler, A. D. J. (1962). Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chandler, A. D. J. (1990). Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clark, J. M. (1923). Studies in the Economics of Overhead Costs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hobsbawm, E. (1962). The Age of Revolution: Europe 1789–1848. London: Phoenix Press.

Hobsbawm, E. (1975). The Age of Capital:1848–1875. London: Phoenix Press.

Hopwood, A. G. (2008). Management accounting research in a changing world. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 20, 3–13.

Hoskin, K. (Ed.) (1996). The ‘awful idea of accountability’: inscribing people into the measurement of objects. In R. Munro and J. Mouritsen (Eds), Accountability: Power, Ethos and the Technologies of Managing, London: International Thomson Business Press.

Johnson, H. T. and Kaplan, R. S. (1987). Relevance Lost: The Rise and Fall of Management Accounting. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Otley, D. T. and Berry, A. J. (1994). Case study research in management accounting and control. Management Accounting Research, 5, 45–65.

Roberts, J. (1996). From discipline to dialogue: individualizing and socializing forms of accountability. In R. Munro and J. Mouritsen (Eds), Accountability: Power, Ethos and the Technologies of Managing. London: International Thomson Business Press.

Stone, W. E. (1969). Antecedents of the accounting profession. The Accounting Review, April, 284–91.

Vatter, W. J. (1950). Managerial Accounting. New York: Prentice Hall.