Chapter 12

Human Resource Decisions

Building on accounting for operations, this chapter explains the components of labour costs and how those costs are applied to decisions affecting the production of goods or services. The relevant cost of labour for decision-making purposes is also explained.

Human resources and accounting

According to Armstrong (1995a, p. 28), ‘personnel management is essentially about the management of people in a way that improves organizational effectiveness.’ Personnel management – or human resources (HR) as it is more commonly called – is a function concerned with job design; recruitment, training and motivation; performance appraisal; industrial relations, employee participation and team work; remuneration; redundancy; health and safety; and employment policies and practices. It is through human resources, that is people, that the marketing and production of goods and services takes place. Historically, as Chapter 1 suggested, employment costs were a large element of the cost of manufacture. However, with improvements in manufacturing, information and communications technologies and the shift to service and knowledge-based industries in most Western economies, people costs have tended to decline in proportion to total costs.

Armstrong (1995b) argued that the tighter grip of accountants on business management and the diffusion of management accounting techniques were forces with which human resource managers had to contend. This was particularly the case where the HR function was devolved to divisionalized business units and under line management control.

Many non-accounting readers ask why the Statement of Financial Position of a business does not show the value of its human assets (what the HR literature refers to as human resource accounting). The knowledge, skills and abilities of people are a key resource in satisfying markets through the provision of goods and services. But people are not owned by a business. They are recruited, trained and developed, then motivated to accomplish tasks for which they are appraised and rewarded. People may leave the business for personal reasons or be made redundant when there is a business downturn. The value of people to the business is in the application of their knowledge, skills and abilities towards the provision of goods and services. Intellectual capital, which was described in Chapter 7, goes some way towards trying to report to shareholders and others the value of human, as well as organizational and customer, capital.

In accounting terms, people are treated as labour, a resource that is consumed – therefore an expense rather than an asset – either directly in producing goods or services or indirectly as a business overhead. This distinction between direct and indirect labour is an important concept that is considered in more detail in Chapter 13.

The cost of labour

The cost of labour can be considered either over the short term or long term. In the short term, the cost of labour is the total expense incurred in relation to that resource, which may, for direct labour, also be calculated as the cost per unit of production, for either goods or services. The cost of labour is the salary or wage cost paid through the payroll, plus the oncost. The labour oncost consists of the non-salary or wage costs that follow from the payment of salaries or wages. The most obvious of these in the UK are National Insurance contributions and pension (or superannuation) contributions made by the business. In other countries oncosts may include health insurance costs, payroll taxes or workers compensation insurance premiums. Virtually all oncosts are expressed as a percentage of salary. The total employment cost may include other forms of remuneration such as bonuses, profit shares and non-cash remuneration, for example share options, expense allowances, business-provided motor vehicles and so on.

A less visible but important element of the cost of labour is the period during which employees are paid but do not work, covering for example public holidays, annual leave and sick leave. A second element of the cost of labour is the time when people are at work but are unproductive, such as when they are on refreshment or toilet breaks, socializing, or during equipment downtimes. These unproductive times all increase the cost of labour in relation to the volume of production of goods or services. The actual at-work and productive time is an important calculation in determining the production capacity of the business (see Chapter 11).

The following example shows how the total employment cost may be calculated for an individual (the oncosts are indicative only as they can vary widely depending on the location and industry of the business):

| £ | ||

| Salary | 30,000 | |

| Oncosts: | ||

| National insurance 10% | 3,000 | |

| Pension contribution 4% | 1,200 | 4,200 |

| 34,200 | ||

| Bonus paid as share options | 1,000 | |

| Total salary cost | 35,200 | |

| Non-salary benefits: | ||

| Cost of motor vehicle | 4,000 | |

| Expense allowance | 500 | 4,500 |

| Total employment cost | 39,700 |

Assuming a five-day week and 20 days’ annual leave, five days’ sick leave and eight public holidays per annum (the actual calculation will vary by location and industry), the actual days at work (the production capacity) can be calculated as:

| Working days 52 × 5 | 260 | |

| Less: | ||

| Annual leave | 20 | |

| Sick leave | 5 | |

| Public holidays | 8 | 33 |

| Actual days at work | 227 |

The total employment cost per working day for this employee is therefore £174.89 (£39,700/227 days). Assuming that the employee works eight hours per day and the employee is productive for 80% of the time at work, then the cost per hour worked is £27.33 (£174.89/(8 × 80%)).

The employee, taking home £30,000 for a 40-hour week, may consider their cost of employment as £14.42 per hour (£30,000/52/40), even though they will not receive this amount as income tax has to be deducted. From the employer’s perspective, however, this example shows the total employment cost and the effect of the paid but unproductive time, which almost doubles the cost to the employer – what is £14.42 per hour to the employee is £27.33 per hour to the employer.

The cost per unit of production can be expressed either as the (total employment) cost per (productive) hour worked, in this case a labour cost per hour of £27.33, or as a cost per unit of production. If an employee during their productive hours completes four units of a product, the direct labour cost per unit of production is £6.83 (£27.33/4). If a service employee processes five transactions per hour, the direct labour cost per unit of production (a transaction is still a unit of production) is £5.47 (£27.33/5).

The calculation of the cost of labour is shown in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 The cost of labour.

| Cost | Time |

| Salaries and wages + oncosts (pensions, | Working days – annual leave, sick leave, |

| National Insurance etc.) + non-salary | public holidays, etc. = actual days at work |

| benefits (motor vehicles, expenses etc.) = | × at work hours × productivity = actual |

| total employment cost | hours worked |

|

|

In the longer term, a business may want to take a broader view of the total cost of employment. Many costs are incurred over and above the salary and wages paid to employees, who must be recruited and trained before they can be productive. A longer term approach to the total cost of employment may include recruitment and training costs as additional costs of employment. In relation to short term and long term, an important issue arises as to whether the cost of labour is a fixed or variable cost, following the distinction made in Chapter 10. It is clear that materials used in production are a variable cost, as no materials are consumed if there is no production, but the situation for labour is more complex. Accountants have historically considered labour that is consumed in producing goods or services, i.e. direct labour, as a variable cost. This is because it is usually expressed as a cost per unit of production, which, in total, increases or decreases in line with business activity (but often ignores the cost of spare capacity, which was explained in Chapter 11). Changing legislation, the influence of trade unions and business HR policies have meant that in the very short term, all labour takes on the appearance of a fixed cost. The consultation process for redundancy takes time, and legislation such as Transfer of Undertakings Protection of Employment (TUPE) in the UK or the European Union Acquired Rights Directive secures the employment rights of labour that is transferred between organizations, a fairly common occurrence as a consequence of outsourcing arrangements or business mergers and acquisitions. Consequently, reflecting the underlying practicality, many businesses now account for direct labour as a fixed cost.

Relevant cost of labour

The distinction between fixed and variable costs is not sufficient for the purpose of making decisions about labour in the very short term as, in that short term, labour will still be paid irrespective of whether employees are fully utilized or have spare capacity. Therefore, in the short term, a business bidding for a special order should only take into account the relevant costs associated with that decision. As we saw in Chapter 11, the relevant cost is the future, incremental cash flow, i.e. the cost that will be affected by a particular decision to do (or not to do) something. As decision making is not concerned with the past, historical (or sunk) costs are irrelevant. The relevant cost may be an additional cash payment or an opportunity cost, i.e. the loss from an opportunity forgone. For example, in the case of full capacity, the relevant cost could be the additional labour costs (e.g. overtime or casual labour) that may have to be incurred, or the opportunity cost following from the inability to sell products/services (e.g. both the loss of income from a particular order and the wider potential loss of customer goodwill).

Costs that are the same irrespective of the alternative chosen are irrelevant for the purposes of a particular decision, as there is no financial benefit or loss as a result of either choice. The costs that are relevant may change over time and with changing circumstances. This is particularly so with the cost of labour, where full capacity in one week or month may be followed by surplus capacity in the following week or month.

Where there is spare capacity, with surplus labour that will be paid irrespective of whether a particular decision is taken or not, the labour cost is irrelevant to the decision, because there is no future incremental cash flow. Where there is casual labour or use of overtime and the decision causes that cost to increase (or decrease), the labour cost is relevant. Where labour is scarce and there is full capacity, so that labour has to be diverted from alternative work involving an opportunity cost, the opportunity loss is the relevant cost.

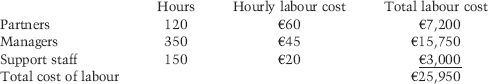

For example, Brown & Co. is a small management consulting firm that has been offered a market research project for a client. The estimated workloads and labour costs for the project are:

| Hours | Hourly labour cost | |

| Partners | 120 | €60 |

| Managers | 350 | €45 |

| Support staff | 150 | €20 |

There is at present a shortage of work for partners, but this is a temporary situation. Managers are fully utilized and if they are used on this project, other clients will have to be turned away, which will involve the loss of revenue of €100 per hour. Support staff are paid on a casual basis and are only hired when needed. Fixed costs are €100,000 per annum.

The relevant cost of labour to be used when considering this project can be calculated by considering the future, incremental cash flows:

| Partners | 120 hours – irrelevant as unavoidable surplus labour | Nil |

| Managers | 350 hours @ €100 – this is the opportunity cost of the lost revenue from clients who are turned away | €35,000 |

| Support staff | 150 hours @ €20 cost | 3,000 |

| Relevant cost of labour | €38,000 |

However, the accounting system would have recorded the cost of labour (based on timesheets and hourly labour costs) as:

While the accounting system records the historic cost, in this instance it does not take into account the opportunity cost of the lost revenue. Accounting costs are therefore a limited way in which to make management decisions. The relevant cost approach identifies the future, incremental cash flows associated with acceptance of the order. The relevant cost ignores the cost of partners as there is no future, incremental cash flow. The cost of managers is the opportunity cost – the lost revenue from the work to be turned away. The support staff cost is due to the need to employ more temporary staff. Fixed costs are irrelevant as they are unaffected by this project. In this case, Brown & Co. would be worse off by taking the market research project at a price less than €38,000. If it is unable to achieve a higher price, the existing clients should be retained at the €100 rate for managers.

Chapter 11 introduced outsourcing as a business strategy that has been in favour with many businesses to reduce the cost of labour. The following example illustrates the relevant costs of labour in an outsourcing decision.

Newgo Industries operates a telephone call centre as part of a larger company. The call centre employs 10 telephone operators at a total employment cost of $40,000 per annum each. Each operator is on a short-term employment contract which is cancellable with a month’s notice. Management salaries cost $50,000 per annum and the call centre is charged a rental and utilities cost by head office of $20,000 per annum. An offshore company has offered to undertake the call centre function for $325,000 per annum. If the call centre is outsourced, management salaries will continue unchanged and the head office charge cannot be avoided. Table 12.2 shows the total cost under each alternative. Table 12.3 shows the relevant costs for each alternative, by eliminating those costs which are unavoidable under both alternatives. Both Tables 12.2 and 12.3 show that the cost differential is $75,000 per annum and therefore, from a financial perspective, the outsourcing should proceed.

Table 12.2 Total costs of call centre and outsourcing.

| Retain call centre | Outsourcing | |

| Telephone operators, 10 @ $40,000 | 400,000 | |

| Management | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| Office rental and utilities | 20,000 | 20,000 |

| Outsourcing cost | 0 | 325,000 |

| Total relevant cost | $470,000 | $395,000 |

Table 12.3 Relevant costs of call centre and outsourcing.

| Retain call centre | Outsourcing | |

| Telephone operators, 10 @ $40,000 | 400,000 | |

| Outsourcing cost | ______ | 325,000 |

| Total relevant cost | $400,000 | $325,000 |

Note in this example that the salaries of telephone operators are a relevant cost as these costs can be avoided by giving a month’s notice. Management salaries are not a relevant cost as they are incurred irrespective of the decision to outsource. This example shows how it is important in any calculation of relevant costs to be sure about which costs involve future incremental cash flows, i.e. which costs are avoidable and which costs are unavoidable. However, it is also important to remember that financial information is only one element of a business decision such as outsourcing. Other factors that must be considered (but which are often difficult to quantify) include quality, customer service and reputation.

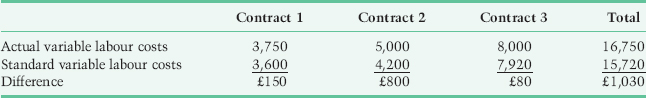

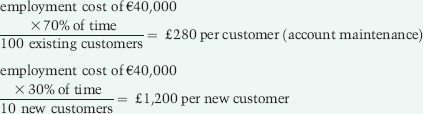

The following case studies illustrate how an understanding of labour costs and unused capacity can influence management decisions.

Table 12.4 DMC budget.

Table 12.5 DMC actual results.

Table 12.6 DMC loss of contribution.

Table 12.7 DMC cost of unused capacity.

Table 12.8 DMC variable costs.

Conclusion

This chapter has calculated the cost of labour and contrasted earnings from an employee’s perspective with the total cost of employment to an employer. We have also developed the idea of relevant costs (introduced in Chapter 11) with examples of the relevant cost of labour.

Unfortunately, one of the first business responses to a downturn in profits is frequently to make staff redundant. Although the redundancy payments will be recognized as a cost in the Income Statement, there is a substantial social cost, not reflected in the financial reports of a business. These social effects will be borne by the redundant employee, while the financial burden of unemployment benefits may be borne by the taxpayer (see Chapter 5 for a discussion). This short-term concern with reducing labour cost often ignores the potential for cost improvement that can arise from a better understanding of business processes. It also ignores the investment in human capital: the knowledge, skills and experience of employees made redundant and the long-term costs associated with recruitment and training that will have to be incurred again if business activity returns to higher levels.

References

Armstrong, M. (1995a). A Handbook of Personnel Management Practice (5th edn). London: Kogan Page.

Armstrong, P. (1995b). Accountancy and HRM. In J. Storey (Ed.), Human Resource Management: A Critical Text, London: International Thomson Business Press.

| Raw materials | $4 |

| Production labour | 16 |

| Variable manufacturing overhead | 8 |

| Fixed manufacturing overhead | 10 |

| Total | $38 |

| Partners | €200,000 |

| Juniors | €450,000 |

| Production labour | $200 |

| Raw materials | 600 |

| Variable overheads | 100 |

| Fixed overheads | 300 |

| Total | $1,200 |

- Calculate the relevant costs of the alternative choices (show your workings) and make a recommendation to management as to which choice to accept.

- How would your recommendation differ if Bendix employees were on temporary contracts with no notice period?

- Explain the significance of a stock valuation of $1,300 for the VX-1 at the end of the last accounting period.

Table 12.9 Victory Products profit report.

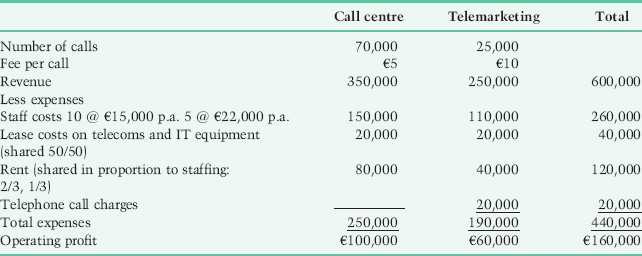

Table 12.10 Call Centre Services.