Chapter 3

Recording Financial Transactions and the Principles of Accounting

In order to understand the accounting process, we need to understand how accounting captures information that is subsequently used for producing financial statements and for managerial planning, decision making and control purposes. This chapter describes how business events are recorded as transactions into an accounting system using the double-entry method that is the foundation of accounting. The elements of the accounting system are introduced: assets; liabilities; income; expenses and equity. We introduce a simple form of the Income Statement and Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet) and explain the basic principles of accounting that underlie how financial statements are produced. Finally, the chapter introduces one of the first limitations of accounting systems – the calculation of ‘cost’ for decision making, and how cost may be interpreted in multiple ways.

Business events, transactions and the accounting system

Businesses exist to make a profit. They do this by producing goods and services and selling those goods and services at a price that covers their cost. Conducting business involves a number of business events such as buying equipment, purchasing goods and services, paying expenses, making sales, distributing goods and services etc. In accounting terms, each of these business events is a transaction. A transaction is the financial description of each business event.

It is important to recognize that transactions are a financial representation of the business event, measured in monetary terms. This is only one perspective on business events, albeit the one considered most important for accounting purposes. A broader view is that business events can also be recorded in non-financial terms, such as measures of product/service quality, speed of delivery, customer satisfaction etc. These non-financial performance measures (which are described in detail in Chapter 4) are important aspects of business events that are not captured by financial transactions. This is a limitation of accounting as a tool of business decision making that the reader must always bear in mind.

Each transaction is recorded on a source document that forms the basis of recording in a business’s accounting system. Examples of source documents are invoices and cheques, although increasingly source documents are records of electronic transactions, such as electronic funds transfer. The accounting system, typically computer based (except for very small businesses), comprises a set of accounts that summarize the transactions that have been recorded on source documents and entered into the accounting system. Accounts can be considered as ‘buckets’ within the accounting system containing similar transactions (e.g. sales income, salary payments, inventory).

There are five types of accounts:

- Assets: things the business owns.

- Liabilities: debts the business owes.

- Income: the revenue generated from the sale of goods or services.

- Expenses: the costs incurred in producing the goods and services

- Equity (or capital): the investment made by shareholders into the business.

The main difference between these categories is that business profit is calculated as:

![]()

while the equity or capital of the business (the owner’s investment) is calculated as

![]()

Financial statements comprise the Income Statement (which used to be called the Profit and Loss account and which now forms part of the Statement of Comprehensive Income) and the Statement of Financial Position (previously termed Balance Sheet). Both are produced from the information in the accounting system (see Chapter 6).

The double entry: recording transactions

Businesses use a system of accounting called double entry, which derives from the late fifteenth-century Italian city-states (see Chapter 1). The double entry means that every business transaction affects two accounts. Those accounts may increase or decrease. Accountants record the increases or decreases as debits or credits, but it is not necessary for non-accountants to understand this distinction. It is sufficient for our purposes to:

Figure 3.1 Business events, transactions and the accounting system.

Transactions may take place in one of two forms:

- Cash: If the business sells goods/services for cash, the double entry is an increase in income and an increase in the bank account (an asset). If the business buys goods/services for cash, either an asset or an expense will increase (depending on what is bought) and the bank account will decrease.

- Credit: If the business sells goods/services on credit, the double entry is an increase in debts owed to the business (called Receivables in financial statements but commonly referred to as Debtors, an asset) and an increase in income. If the business buys goods/services on credit, either an asset or an expense will increase (depending on what is bought) and the debts owed by the business will increase (called Payables in financial statements, but commonly referred to as Creditors, a liability).

When goods are bought for resale, they become an asset called Inventory (commonly referred to as Stock). When the same goods are sold, there are two transactions:

In this way, the profit is the difference between the price at which the goods were sold (1 above) and the purchase cost of the same goods (2 above). Importantly, the purchase of goods into inventory does not affect profit until the goods are sold.

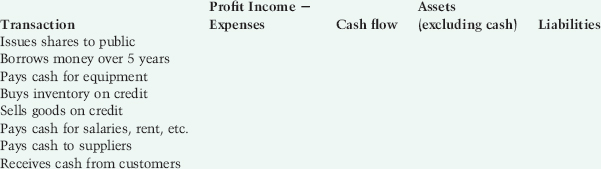

Some examples of business transactions and how the double entry affects the accounting system are shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Business transactions and the double entry.

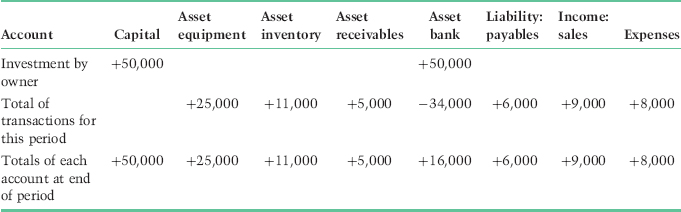

The accounts are all contained within a ledger, which is simply a collection of all the different accounts for the business. The ledger would summarize the transactions for each account, as shown in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Summarizing business transactions in a ledger.

In the example in Table 3.2 there would be a separate account for each type of expense (wages, cost of sales, advertising), but for ease of presentation in this text these accounts have been placed in a single column. The ledger is the source of the financial statements that present the performance of the business. However, the ledger would also contain the balance of each account brought forward from the previous period. In our simple example, assume that the business commenced with £50,000 in the bank account that had been contributed by the owner (the owner’s capital). Table 3.3 shows the effect of the opening balances.

Table 3.3 Summarizing business transactions with opening balances in a ledger.

Extracting financial information from the accounting system

To produce financial statements we need to separate the accounts for income and expenses from those for assets and liabilities. In this example, we would produce an Income Statement (see Table 3.4) based on the income and expenses:

Table 3.4 Income Statement.

| Income | 9,000 | |

| Less expenses: | ||

| Cost of sales | 4,000 | |

| Wages | 3,000 | |

| Advertising | 1,000 | 8,000 |

| Profit | 1,000 |

The Statement of Financial Position lists the assets and liabilities of the business, as shown in Table 3.5. The double-entry system records the profit earned by the business as an addition to the owner’s investment in the business.

Table 3.5 Statement of Financial Position (simple version).

The Balance Sheet must balance, i.e. assets are equal to liabilities plus equity.

![]()

This is called the accounting equation and reflects that all the assets of the business must be financed either by liabilities or by equity (as we saw in Chapter 1). Although shown separately, equity (or capital) is a kind of liability as it is owed by the business to its owners, although there must be special circumstances for it ever to be repaid.

The accounting equation can also be restated as:

![]()

Table 3.5 is a format no longer used for the Statement of Financial Position, but it is shown here as an example because it more clearly shows the accounting equation. The Statement of Financial Position has for many years been shown in a vertical format as shown in Table 3.6.

Table 3.6 Statement of Financial Position.

| Assets: | |

| Equipment | 25,000 |

| Inventory | 11,000 |

| Receivables | 5,000 |

| Bank | 16,000 |

| Total assets | 57,000 |

| Liabilities: | |

| Payables | 6,000 |

| Net assets | 51,000 |

| Equity: | |

| Owner’s original investment | 50,000 |

| Plus profit for period | 1,000 |

| Owner’s equity | 51,000 |

There are some important points to note about Table 3.6:

Working capital (see Chapter 7) is the investment in assets (less liabilities) that continually revolve in and out of the bank, comprising receivables, inventory, payables and the bank balance itself (in this case £32,000 less £6,000 = £26,000). Note that Equipment (£25,000) is not part of working capital as it forms part of the business infrastructure. The purchase of infrastructure is commonly called capital expenditure (often abbreviated as cap ex), and is also referred to as capitalizing an amount of money paid out, which does not affect profit. Whether a payment is treated as an expense (which affects profit) or as an asset (which appears in the Statement of Financial Position) is important, as it can have a significant impact on profit, which is one of the main measures of business performance.

Both the Income Statement and the Statement of Financial Position are described in detail in Chapter 6. In financial reporting, as this chapter and Chapters 6 and 7 will show, there are strict requirements for the content and presentation of financial statements. One of these requirements is that the reports (produced from the ledger accounts) are based on line items. Line items are the generic types of assets, liabilities, income, expenses and equity that are common to all businesses. This is an important requirement as all businesses are required to report their expenses using much the same line items, to ensure comparability between companies.

Basic principles of accounting

Basic principles or conventions have been developed over many years and form the basis upon which financial information is reported. These principles include:

- accounting entity;

- accounting period;

- matching principle;

- monetary measurement;

- historic cost;

- going concern;

- conservatism;

- consistency.

Each is dealt with in turn below.

Accounting entity

Financial statements are produced for the business, independent of the owners – the business and its owners are separate entities. This is particularly important for owner-managed businesses where the personal finances of the owner must be separated from the business finances. The problem caused by the entity principle is that complex organizational structures are not always clearly identifiable as an ‘entity’ (see the Enron case study in Chapter 5).

Accounting period

Financial information is produced for a financial year. The period is arbitrary and has no relationship with business cycles. Businesses typically end their financial year at the end of a calendar or national fiscal year. The business cycle is more important than the financial year, which after all is nothing more than the time taken for the Earth to revolve around the Sun. If we consider the early history of accounting, merchant ships did not produce monthly accounting reports. They reported to the ships’ owners at the end of the business cycle, when the goods they had traded were all sold and profits could be calculated meaningfully. However, companies are required to report to shareholders on an annual basis.

Matching principle

Closely related to the accounting period is the matching (or accruals) principle, in which income is recognized when it is earned and expenses when they are incurred, rather than on a cash basis. The accruals method of accounting provides a more meaningful picture of the financial performance of a business from year to year. However, the preparation of accounting reports requires certain assumptions to be made about the recognition of income and expenses. One of the criticisms made of many companies is that they attempt to ‘smooth’ their reported performance to satisfy the expectations of stock market analysts in order to maintain shareholder value. This practice has become known as ‘earnings management’. A significant cause of the difficulties faced by WorldCom was that expenditure had been treated as an asset in order to improve reported profits (see the case study in Chapter 5).

Monetary measurement

Despite the importance of market, product/service quality, human, technological and environmental factors, accounting records transactions and reports information in purely financial terms. This provides an important but limited perspective on business performance. The criticism of accounting numbers is that they are lagging indicators of performance. Chapter 4 considers non-financial measures of performance that are more likely to present leading indicators of performance. An emphasis on financial numbers tends to overlook important issues of customer satisfaction, quality, innovation and employee morale, which have a major impact on business performance. It also means that these essential ingredients to a successful business may not be given the same weighting as that given to financial information.

Historic cost

Accounting reports record transactions at their original cost less depreciation (see Chapter 6), not at market (realizable) value or at current (replacement) cost. The historic cost may be unrelated to market or replacement value. Under this principle, the Statement of Financial Position does not attempt to represent the value of the business and the owner’s equity is merely a calculated figure rather than a valuation of the business. The Statement of Financial Position excludes assets that have not been purchased by a business but have been built up over time, such as customer goodwill, brand names etc. The market-to-book ratio (MBR) is the market value of the business divided by the original capital invested. Major service-based and high technology companies such as Apple and Microsoft, which have enormous goodwill and intellectual property but a low asset base, have high MBRs because the stock market values shares by taking account of information that is not reflected in accounting reports, in particular the company’s expected future earnings.

Going concern

The financial statements are prepared on the basis that the business will continue in operation. Many businesses have failed soon after their financial statements have been prepared on a going concern basis, making the asset values in the Statement of Financial Position impossible to realize. As asset values after the liquidation of a business are unlikely to equal historic cost, the continued operation of a business is an important assumption. The going concern principle is a significant limitation of financial statements as the case study on Carrington Printers in Chapter 7 reveals.

Conservatism

Accounting is a prudent practice, in which the sometimes over-optimistic opinions of non-financial managers are discounted. A conservative approach tends to recognize the downside of events rather than the upside. However, as mentioned above, the pressure on listed companies from analysts to meet stock market expectations of profitability has resulted from time to time in earnings management practices, such as those that led to problems at Enron and WorldCom.

Consistency

The application of accounting principles should be consistent from one year to the next. Where those principles vary, the effect on profits must be separately disclosed. However, some businesses have tended to change their rules, even with disclosure, in order to improve their reported performance, explaining the change as a once-only event.

These basic principles have been elaborated by International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and the Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements, both of which are described in Chapter 6.

One of the most important pieces of financial information for managers concerns cost, which forms the basis for most of the chapters in Part III. The calculation of cost is influenced in large part by accounting principles and the requirements of financial reporting. However, the cost that is calculated for financial reporting purposes may have limited decision usefulness for managers.

Cost terms and concepts: the limitations of financial accounting

Cost can be defined as ‘a resource sacrificed or foregone to achieve a specific objective’ (Horngren et al., 1999, p. 31).

Accountants define costs in monetary terms, and while this book focuses on monetary costs, readers should recognize that there are not only financial costs but non-financial (or at the very least difficult to measure) human, social and environmental costs, and these latter costs are not reported in the financial statements of companies. For example, making employees redundant causes family problems (a human cost) and transfers to society the obligation to pay social security benefits (a social cost). Pollution causes long-term environmental costs that are also transferred to society. These are as important as (and perhaps more important than) financial costs, but they are not recorded by accounting systems (see Chapter 7 for a discussion of corporate social responsibility). The exclusion of human, social and environmental costs is a significant limitation of accounting.

For planning, decision-making and control purposes, cost is typically defined in relation to a cost object, which is anything for which a measurement of costs is required. While the cost object is often an output – a product or service – it may also be a resource (an input to the production process), a process of converting resources into outputs, or an area of responsibility (a department or cost centre) within the organization. Examples of inputs are materials, labour, rent, advertising, etc. These are line items (see above). Examples of processes are purchasing, customer order processing, order fulfilment, dispatch, etc. Departments or cost centres may include Purchasing, Production, Marketing, Accounting, etc. Other cost objects are possible when we want to consider profitability, e.g. the cost of dealing with specific customers is important for customer profitability analysis, or the costs of a distribution channel when we compare the profitability of different methods of distribution.

Businesses typically report in relation to line items (the resource inputs) and responsibility centres (departments or cost centres). This means that decisions requiring cost information on business processes and product/service outputs are difficult, because most accounting systems (except activity-based systems, as will be described in Chapter 13) do not provide adequate information about these other cost objects. Reports on the profitability of each product, each customer or distribution channel are rarely able to be produced from the traditional financial accounting system and must be determined through management accounting processes that use, but are not incorporated within, traditional accounting systems (however, the more sophisticated enterprise resource planning systems, see Chapter 9, can provide much of this more comprehensive information).

Businesses may adopt a system of management accounting to provide this kind of information for management purposes, but rarely will this second system reconcile with the external financial statements because the management information system may not follow the same accounting principles described in this chapter and in Chapter 6. Therefore, the requirement to produce financial statements based on line items and responsibility centres, rather than more meaningful cost objects (customers, processes, etc.), is a second limitation of accounting as a tool of decision making.

The notion of cost is also problematic because we need to decide how cost is to be defined. If, as Horngren et al. defined it, cost is a resource sacrificed or forgone, then one of the questions we must ask is whether that definition implies a cash cost or an opportunity cost. A cash cost is the amount of cash expended (a valuable resource), whereas an opportunity cost is the lost opportunity of not doing something, which may be the loss of time or the loss of a customer, or the diminution in the value of an asset (e.g. machinery), all equally valuable resources. If it is the cash cost, is it the historical (past) cost or the future cost with which we should be concerned?

For example, is the cost of an employee:

- the historical cash cost of salaries and benefits, training, recruitment etc. paid?

- the future cash cost of salaries and benefits to be paid?

- the lost opportunity cost of what we could have done with the money had we not employed that person, e.g. the benefits that could have resulted from expenditure of the same amount of money on advertising, computer equipment, external consulting services etc.?

Wilson and Chua (1988) quoted the economist Jevons, writing in 1871, that past costs were irrelevant to decisions about the future because they are ‘gone and lost forever’. We call these past costs sunk costs. The problematic nature of calculating costs may have been the source of the comment by Clark (1923) that there were ‘different costs for different purposes’.

This, then, is our third limitation of accounting: what do we mean by cost and how do we calculate it? We return to many of these issues throughout Part III of this book. The point to remember here is that, while financial statements are important and do report many costs, they are not necessarily the costs that should be used by managers for decision making.

Conclusion

This chapter has described how an accounting system captures, records, summarizes and reports financial information using the double-entry system of recording financial transactions in accounts. It has introduced the Income Statement and Statement of Financial Position. The simple examples of financial statements introduced in this chapter (which are dealt with in more detail in Chapters 6 and 7) rely on the separation between assets, liabilities, income, expenses and equity. This chapter has also identified the basic principles underlying the accounting process. One of the limitations of financial accounting for managerial decision making is highlighted through a brief introduction to ‘cost’.

References

Clark, J. M. (1923). Studies in the Economics of Overhead Costs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Horngren, C. T., Bhimani, A., Foster, G. and Datar, S. M. (1999). Management and Cost Accounting. London: Prentice Hall.

Wilson, R. M. S. and Chua, W. F. (1988). Managerial Accounting: Method and Meaning. London: VNR International.

| £ | |

| Advertising | 15,000 |

| Bank | 5,000 |

| Equity | 71,000 |

| Income | 135,000 |

| Equipment | 100,000 |

| Payables | 11,000 |

| Receivables | 12,000 |

| Rent | 10,000 |

| Salaries | 75,000 |