Reading B

Otley, D. T., Broadbent, J. and Berry, A. J. (1995). Research in management control: an overview of its development. British Journal of Management, 6, Special Issue, S31–S44. © John Wiley & Sons, Limited. Reproduced with permission.

Questions

Further reading

Berry, A. J., Broadbent, J. and Otley, D. (Eds). (1995). Management Control: Theories, Issues and Practices. London: Macmillan.

Fitzgerald, L., Johnston, R., Brignall, S., Silvestro, R. and Voss, C. (1991). Performance Measurement in Service Businesses. London: Chartered Institute of Management Accountants.

Hopper, T., Otley, D. and Scapens, B. (2001). British management accounting research: whence and whither: opinions and recollections. British Accounting Review, 33, 263–91.

Humphrey, C. and Scapens, R. W. (1996). Theories and case studies of organizational and accounting practices: limitation or liberation? Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 9(4), 86–106.

Kaplan, R. S. and Norton, D. P. (2001). The Strategy-Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Macintosh, N. B. (1994). Management Accounting and Control Systems: An Organizational and Behavioral Approach. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Otley, D. (1999). Performance management: a framework for management control systems research. Management Accounting Research, 10, 363–82.

Otley, D. (2001). Extending the boundaries of management accounting research: developing systems for performance management. British Accounting Review, 33, 243–61.

Scott, W. R. (1998). Organizations: Rational, Natural, and Open Systems (4th edn). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall International, Inc.

Research in Management Control: An Overview of its Development

Summary

This paper builds on a series of earlier reviews of the management control literature (Giglioni and Bedeian, 1974; Hofstede, 1968; Merchant and Simons, 1986; Parker, 1986) and considers the development of the management control literature in the context of organizational theories. Early themes which have provided the roots for the development of the subject area are explored as is more recent work which has evolved both as a continuation and a reaction against them, with Scott’s (1981) framework being used to organize this literature. It is argued that one of the unintended consequences of the influential work of Robert Anthony (1965) has been a restriction of the subject to an accounting-based framework and that this focus needs to be broadened. The review points to the potential of the subject as an integrating theme for the practice and research of management and some themes for future research are suggested.

Introduction

This paper reviews the development of research in management control, building upon other reviews both to examine the roots of the subject from the turn of the century and to demonstrate the depth and breadth of the subject. Four previous reviews form the foundation for our overview.

Giglioni and Bedeian (1974) review the contribution of the general management and organizational theory literature for the period 1900–1972, drawing out several different strands to conclude that

even though control theory has not achieved the level of sophistication of some other management functions, it has developed to a point that affords the executive ample opportunity to maintain the operations of his firm under check.

Parker (1986) argues that accounting control developments lagged developments in the management literature, and criticizes accounting models for offering only an imperfect reflection of management models of control. Hofstede (1968) offers an early survey of the behavioural approach to budgetary control. He explores how the role of budgets has been viewed in accounting theory, in motivation theory, and from the perspective of systems theory. Finally, the brief overview of research into control in complex organizations by Merchant and Simons (1986) takes a broad view of what constitutes control, as does the present paper. It differs, however, in also paying attention to agency theory literature and psychological research both omitted from consideration here.1

It will be argued that one of the unintended consequences of Anthony’s (1965) seminal work is that management control has primarily been developed in an accounting-based framework which has been unnecessarily restrictive. Although radical theorists have studied control processes more extensively, their attention has been focused much more on the exercise of power and its consequences than on the role of control systems as a means of organizational survival. This is an important area, but one which is outside the remit set for this review which is in closer alignment with Mills (1970) who argued for the place of management control as a central management discipline. He suggested that it was a more appropriate integrating discipline for general management courses than the tradition of using business policy or corporate strategy courses. ‘Control’ is itself a highly ambiguous term as evidenced by the difficulty of translating it into many European languages and the list of ‘57 varieties’ in its connotations given by Rathe (1960). Given this diversity some attention will be paid to matters of definition and the establishment of appropriate boundaries for this review.

Anthony’s (1965) classic definition of management control was

the process by which managers assure that resources are obtained and used effectively and efficiently in the accomplishment of the organization’s objectives.

He saw management control as being sandwiched between the processes of strategic planning and operational control; these processes being super-imposed upon an organizational hierarchy to indicate the respective managerial levels at which they operate.

Strategic planning is concerned with setting goals and objectives for the whole organization over the long term. By contrast, operational control is concerned with the activity of ensuring that immediate tasks are carried out. Management control is the process that links the two. Global goals are broken down into sub-goals for parts of the organization; statements of future intent are given more substantive content; long-term goals are solidified into shorter term goals. The process of management control is designed to ensure that the day-to-day tasks performed by all participants in the organization come together in a coordinated set of actions which lead to overall goal specification and attainment. This can be seen primarily as the planning and coordination function of management control. The other side of the management control coin is its monitoring and feedback function. Regular observations and reports on actual achievement are used to ensure that planned actions are indeed achieving desired results.

It may be argued that Anthony’s approach is too restrictive in that it assumes away important problems (see Lowe and Puxty, 1989 for further discussion of these issues). The first problem is concerned with problems of defining strategies, goals and objectives. Such procedures are typically complex and ill-defined, with strategies being produced as much by accident as by design. It is clear that Anthony was aware of the problems of ambiguity and uncertainty when he located these issues in the domain of strategy, but he then avoided their further consideration. The second problem concerns the methods used to control the production (or service delivery) processes, which are highly dependent upon the specific technology in use and which are widely divergent. Anthony conveniently relegates these issues to the realm of operational control. Finally, his textbooks concentrate upon planning and control through accounting rationales and contain little or no discussion of social-psychological or behavioural issues, despite his highlighting the importance of the latter. Anthony’s approach can, thus, be seen as a preliminary ground-clearing exercise, whereby he limits the extent of the problem he sets out to study. In a complex field this was probably a very sensible first step, however, it greatly narrowed the scope of the topic.

A broader view of management control is suggested by Lowe (1971) in a more comprehensive definition:

A system of organizational information seeking and gathering, accountability and feedback designed to ensure that the enterprise adapts to changes in its substantive environment and that the work behaviour of its employees is measured by reference to a set of operational sub-goals (which conform with overall objectives) so that the discrepancy between the two can be reconciled and corrected for.

This stresses the role of a management control system (MCS) as a broad set of control mechanisms designed to assist organizations to regulate themselves, whereas Anthony’s definition is more specific and limited to a narrower sub-set of control activities. Machin (1983) continues this line of thought in his critical review of management control systems as a specialist subject of academic study. He explores each of the terms ‘management’, ‘control’ and ‘system’, defining a research focus:

Those formal, systematically developed, organization-wide, data-handling systems which are designed to facilitate management control which ‘is the process by which managers assure that resources are obtained and used effectively and efficiently in the accomplishment of the organization’s objectives.’

Machin notes that such a definition has the merit of leaving scope for academics to disagree violently whilst still perceiving themselves to be studying the same thing! Further, Machin argues that research in MCSs, led, as it was, by qualified accountants, made the research questions

virtually immune from philosophical analysis,

a critique also reflected in Hofstede’s (1978) criticism of the

poverty of management control philosophy,

− the narrow, accounting focus which had become so prevalent.

Such diverse opinions leave a number of issues to be clarified. First, is the meaning of the term ‘control’. In this review we will include within the definition of control both the ideas of informational feedback and the implementation of corrective actions. Equally, we explicitly exclude the exercise of power for its own sake, restricting ourselves to those activities undertaken by managers which have the intention of furthering organizational objectives (at least, insofar as perceived by managers). We are, thus, primarily concerned with the exercise of legitimate authority rather than power. This is no doubt a controversial position, but gives the review a clear managerial focus.

There is also a distinction to be drawn between management control and financial control, which is of some importance given the accounting domination of the subject in recent years. Financial control is clearly concerned with the management of the finance function within organizations. As such it is one business function amongst many, and comprises but one facet of the wider practice of management control. On the other hand, management control can be defined as a general management function concerned with the achievement of overall organizational aims and objectives. Financial information is thus used in practice to serve two interrelated functions. First, it is clearly used in a financial control role, where its function is to monitor financial flows; that is, it is concerned with looking after the money. Second, it is also often used as a surrogate measure for other aspects of organizational performance. That is, management control is concerned with looking after the overall business with money being used as a convenient measure of a variety of other more complex dimensions, not as an end in itself.

Having set some boundaries, the next section of the paper will provide a brief account of the main themes that have formed the starting point for the development of the field. Whilst well known, these roots cannot be ignored as their influence is reflected in work which continues today. There follows a review of the literature that has evolved over the last 20 years both as a continuation of and as a reaction against those roots, using a heuristic map provided by Scott (1981). Finally, we will suggest possible themes for future development.

The Starting Points

The roots of management control issues lie in early managerial thought. The significance of the work of Weber, Durkheim and Pareto upon the development of managerial thought is well rehearsed. Less well known, but providing an excellent example of the classical management theorists, is the contribution of Mary Parker Follett, described by Parker (1986) as providing almost all of the ideas of modern control theory. Follett saw that the manager controlled not single elements but complex interrelationships and argued that the basis for control lay in self-regulating, self-directing individuals and groups who recognized common interests and objectives. It may be that Follett was an idealist in her search for unity in organizations for she sought a control that was

‘fact control’ not ‘man control’, and ‘correlated control’ rather than ‘superimposed control’.

Further she saw coordination as the reciprocal relating of all factors in a setting that involved direct contact of all people concerned. The application of these

fundamental principles of organisation

was the control activity itself, for the whole point of her principles was to ensure predictable performance for the organization.

Scientific management, another important root of management control, is frequently associated with the work of F.W. Taylor (Miller and O’Leary, 1987), although there were earlier contributors to this movement. For example, Babbage (1832) was concerned with improving manufacture and systems and analysed operations, the skills involved, the expense of each process and suggested paths for improvement. In 1874 Fink (see Wren, 1994) developed a cost accounting system that used information flows, classification of costs and statistical control devices; innovations which led directly to 20th century processes of management control.

What seems to characterize these theorists is an attention to real problems, a scientific approach which centred upon understanding and conceptual analysis, and a wish to solve problems. Their contribution to management control lay in their attention to authority and accountability, an awareness of the need for analytical and budgetary models for control, forging the link between cost and operational activities, and the separation of cost accounting from financial accounting, with the former being a pre-cursor of management accounting and control. However, these practical theorists may have pursued rationality of economic action and the search for universal solutions too far, although their ideas are still current and form the basis for much work in the field, many being echoed in the work of Robert Anthony. The ideas of the common purpose of social organizations along with a concern for the relationship between effectiveness and efficiency foreshadow the concept of autopoesis (the view that systems can have a ‘life of their own’) developed by cyberneticians. These will be examined in the next section.

Evolution of the Management Control Literature

As previously noted, Parker (1986) argued that developments in accounting control have followed and lagged developments in management theory. Developments in management control seem to have followed a similar pattern, so we use the schema suggested by Scott (1981) for categorizing developments in organization theory as a framework for organizing this part of our review. We would argue that systems thinking has had an important influence on the development of MCSs and Scott’s schema is based on a systems approach, so it is to this we now turn.

Cybernetics and systems theory

Organizational theory in general and management control research in particular have been influenced considerably by cybernetics (the science of communication and control (Weiner, 1948)). These insights have been extended in the holistic standpoint taken by general systems theory and the ‘soft systems’ approach (Checkland, 1981). Its central contribution has been in the systemic approach it adopts, causing attention to be paid to the overall control of the organization, in contrast to the systematic approach dominant in accounting control, which has often assumed that the multiplication of ‘controls’ will lead inexorably to overall ‘control’, a view roundly routed by Drucker (1964). Cybernetics and systems theory have developed in such an interlinked manner that it is difficult to draw a meaningful dividing line between them (for a fuller survey see Otley, 1983), although a simple distinction would be to suggest that cybernetics is concerned with closed systems, whereas systems theory specifically involves a more open perspective.

The major contribution of cybernetics has been in the study of systems in which complexity is paramount (Ashby, 1956); it attempts to explain the behaviour of complex systems primarily in terms of relatively simple feedback mechanisms (Wisdom, 1956). There have been a number of attempts to apply cybernetic concepts to the issue of management control, but these have all been of a theoretical nature, albeit based on general empirical observation. The process of generating feedback information is fundamental to management accounting on which much management control practice rests, although this is not usually elaborated in any very insightful manner. However, Otley and Berry (1980) developed Tocher’s (1970) control model and applied it to organizational control. They maintain that effective control depends upon the existence of an adequate means of predicting the consequences of alternative control actions. In most organizations such predictive models reside in the minds of line managers, rather than in any more formal form, and they argue that improvements in control practice need to focus on improving such models. It is also argued that feed-forward (anticipatory) controls are likely to be of more importance than feedback (reactive) controls. This echoes previous comments by authors such as Ashby (1956), who points to the biological advantages in controlling not by error but by what gives rise to error, and Amey (1979) who stresses the importance of anticipatory control mechanisms in business enterprises.

Arguably the most insightful use of cybernetic ideas applied to management practice is also one of the earliest. Vickers (1965, 1967) applied many cybernetic ideas to management practice during the 1950s. Although developed in a primarily closed systems context, he also started to explore the issue of regulating institutions from a societal perspective. This is also a major theme of Stafford Beer, most comprehensively in his 1972 book Brain of the Firm. Here he uses the human nervous system as an analogy for the control mechanisms that need to be adopted at various levels in the control of an organization. However, Beer’s major contribution lies in his attempt to tackle issues of the overall societal and political context within which more detailed organizational forms and controls emerge. This is a theme which is picked up, albeit in a very different form, by the radical theorists of the 1980s and 1990s. The standard concepts of the cybernetic literature do not have such a straightforward application to the issue of organizational control as some presentations of them tend to imply. However, they do provide a language in which any of the central issues of management control may be expressed.

Further progress comes from the use of general systems theory which stresses the importance of emergent properties of systems, that is, properties which are characteristic of the level of complexity being studied and which do not have meaning at lower levels; such properties are possessed by the system but not by its parts. Systems thinking is thus primarily a tool for dealing with high levels of complexity, particularly with reference to systems which display adaptive and apparently goal-seeking behaviour (Lilienfeld, 1978). Some useful conceptual distinctions are drawn by Lowe and McInnes (1971) who attempt to apply a systems approach to the design of MCSs. An important extension to the realm of so-called ‘soft’ systems (i.e. systems which include human beings, where objectives are vague and ambiguous, decision-making processes ill-defined, and where, at best, only qualitative measures of performance exist) has been made by the Checkland school at Lancaster (Checkland, 1981; Wilson, 1984).

One of the central issues with which the ‘soft’ systems methodology has to cope is the imputation of objectives to the system. In many ways this methodology reflects the verstehen (or insight) tradition of thought in sociology, where great stress is laid upon the accuracy and honesty of observation, the sensitivity and perception of the observer, and on the imaginative interpretations of observations. Although the soft systems approach has had considerable success in producing solutions to real problems, it does not appear to have contributed to the development of the theory of control in the normal academic sense. It is very much an applied problem-solving methodology in its present form rather than a research method designed to yield generalizable explanations, although it undoubtedly has further potential in this area. This raises the issue of the nature and type of theories that can be expected in such a complex area of human and social behaviour.

A framework to map developments in management control research

Scott (1981) analysed the development of organization theory using two dimensions. First, he saw a transition from closed to open systems models of organization, reflecting the influence of systems ideas. Prior to 1960 most theorists tended to assume that organizations could be understood apart from their environments, and that most important processes and events were internal to the organization. After that date it was increasingly recognized that organizations were highly interdependent with their environments, and that boundaries are both permeable and variable. Second, he distinguished between rational and natural systems models. The rational systems model assumes that organizations are purposefully designed for the pursuit of explicit objectives, whereas the natural systems model emphasizes the importance of unplanned and spontaneous processes, with organically emerging informal structures supplementing or subduing rationally designed frameworks. The distinction between rational and natural systems is applicable to both sides of the closed-open system divide, resulting in the definition of the four approaches.

We use these categories to summarize work in MCSs, although we recognize that such categorization is not necessarily ‘neat’. Organizations can be viewed as being both rational and natural (Thompson, 1967; Boland and Pondy, 1983); they are often intentionally designed to achieve specific purposes, yet also display emergent properties. It can be argued that each successive theoretical development provides an additional perspective which is helpful in understanding organizational processes, and which is likely to be additional and complementary to those which have preceded it. However, it is also recognized that this is a controversial statement that would not be accepted by some of those adopting a post-modernist viewpoint.

The Closed Rational Perspective

This work is characterized by being both universal in orientation and systematic in approach, scientific management being a typical example. In the management control literature we find a continuing emphasis on rational solutions, implicitly assuming a closed systems model of organization, which are universalistic in nature. Indeed, this can also be seen in much of the modern popular management literature, where a universal ‘how-to-do-it’ approach continues to find a ready market.

From a research point of view, there is much work which has sought to identify the ‘one best way’ to operate a control system. An excellent example of this approach applied to budgetary control is that conducted by Hofstede (1968). He sought to reconcile the US findings that budgets were extensively used in performance evaluation and control, but were associated with negative feelings on the part of many managers and dysfunctional consequences to the organization, with the European experience that budgets were seen positively but were little used. Multiple perspectives are brought to bear, including systems theory, although this draws primarily on cybernetics. His conclusions list several pages of recommendations as to how budgets could be used effectively without engendering negative consequences, and indicate an implicit universalistic orientation. Similarly, the well known text co-authored by Anthony and a host of collaborators (see for example, Anthony et al., 1984) also clearly falls into the closed rational mode with its heavy emphasis on accounting controls.

The Closed Natural Perspective

The closed natural approach is centred around an increasing interest in the behavioural consequences of control systems operation. This was perhaps first introduced to the control literature by Argyris (1952) in his article entitled ‘The Impact of Budgets on People’, an emphasis reversed neatly almost 20 years later by Schiff and Lewin (1970) in their article ‘The Impact of People on Budgets’. Lowe and Shaw (1968) discussed the tendency of managers to bias budgetary estimates that were subsequently used for control purposes. Buckley and McKenna (1972) were able to publish a review article summarizing current knowledge on the connection between budgetary control and managerial behaviour in the early 1970s. Mintzberg followed his 1973 study of the nature of managerial activity with a 1975 study of the impediments to the use of management information, which dealt with many of the behavioural issues in the operation of control systems. There was thus a growing awareness of the human consequences of control systems use and operation beginning to emerge in the early 1970s, perhaps lagging some 20 years behind the equivalent human relations movement in the organization theory literature.

A behavioural perspective on the theme of managerial performance evaluation also began to emerge at this time. Hopwood (1972, 1974a) identified the different styles that managers could adopt in their use of accounting information and studied their impact on individual behaviour and (implicitly) organizational performance. Rhaman and McCosh (1976) sought to explain why different uses of accounting control information were observed, and concluded that both individual characteristics and organizational climate were significant factors. A study by Otley (1978) yielded almost exactly contrary results to those of Hopwood (1972) because the research site had significant differences; the conflicting findings could be reconciled only by adopting a contingent approach, a task that was more thoroughly undertaken by Hirst (1981).

The idea that systems used to evaluate performance are affected by the information supplied by those being evaluated has led to the concept of information inductance (Prakash and Rappaport, 1977; Dirsmith and Jablonsky, 1979). This generalized the observations of information bias and manipulation reported previously as just one manifestation of a more general phenomenon. Such work was extended by Birnberg et al. (1983) into a unified contingent framework, based on the ideas of Thompson (1967), Perrow (1970) and Ouchi (1979).

Despite the categorization of organizational contingency theorists into the open systems box by Scott (1981), the early contingent work in accounting-based control systems has a clear closed systems flavour. It was only in the late 1970s that the open systems ideas in contingency theory, which followed primarily from the use of environment as a contingent variable, began to be reflected in the management control literature. This parallels developments in Organization Theory (OT), for it is arguable that early contingent work by writers such as Woodward (1958, 1965) concentrated on internal factors such as technology, and did not adopt an open systems approach until later. Thus, texts in the management control area, such as Emmanuel et al. (1985, 1990), Merchant (1985), and Johnson and Gill (1993) which recognized the behavioural aspects of MCSs as well as adopting some tenets of the contingency framework, tend to lie along the boundary of the closed natural category and the open rational approach.

The Open Rational Perspective

As in OT, the emergence of an open systems perspective was accompanied by a return to more rational approaches and a relative neglect of the natural (albeit) closed approaches of the preceding years. The recognition of the external environment, key to the open systems approach, had never been strong in the early MCS literature. However, in the early 1970s there was a movement towards an open systems perspective, if only from a theoretical standpoint, an approach well illustrated by the collection of readings in the monograph New Perspectives in Management Control (Lowe and Machin, 1983). This approach was most cogently led by Lowe (1971) in an article which clearly recognizes the coalition of stakeholders involved in an enterprise (a concept used by Scott (1981) as an exemplar of an open systems approach) and the need for adaptation to the external environment. It is further clarified in Lowe and McInnes’ (1971) article which adds the concept of resolution level. At the same time Beer (1972) was developing his own, somewhat idiosyncratic, approach and moving beyond cybernetics into more general systems analysis drawing heavily on neurophysiological ideas.

More significant, empirically, was the development of the contingency theory of management accounting control systems (summarized by Otley, 1980). Although several contingent variables were shown to be significant (e.g. technology, environment, organizational structure, size, corporate strategy), it was the impact of the external environment in general, and of external uncertainty in particular, that most clearly indicated the adoption of an open systems perspective. It is this distinction that marks the divergence of the study of management accounting systems, which have steadfastly retained their internal orientation (despite valiant attempts by a few proponents of so-called ‘strategic management accounting’ (Simmonds, 1981; Bromwich, 1990), and the study of the wider area of management control systems. Within management accounting, contingency theory waned in the early 1980s, to be replaced by various critical approaches in Europe, and to continue down a universalistic track in the US with the burgeoning popularity of activity-based costing under the leadership of Kaplan (1983) in particular. The wider study of control systems picked up on the neglected variable of corporate strategy at this point, which led to a small but significant stream of work most notably by Govindarajan and Gupta (1985) and Simons (1987, 1990, 1991, 1995).

The Open Natural Perspective

There are two developments which can be seen to mark a movement into this final perspective, which are illustrated by the collection of papers published in the monograph Critical Perspectives in Management Control (Chua et al., 1989). First, there is a recognition that contingent variables are not to be seen as deterministic drivers of control systems design. In particular, the environment is not to be seen only as a factor to be adapted to, but also something which can itself be manipulated and managed. Second, there is the recognition of the political nature of organizational activity. However, although radical theorists have clearly been concerned with the exercise of power in and around organizations, it is not clear that they have contributed greatly to the study of control in its adaptive sense, nevertheless they have clearly indicated the complex political environment within which control systems have to function (see, for example, Ezzamel and Watson, 1993; Hogler and Hunt, 1993). This touches on the theme of legitimacy at various levels of resolution and addresses the question of how legitimacy becomes established and how it works through to different hierarchical levels in organizations. Examples of such work include research examining the reforms of the NHS using a post-modern perspective (Preston, 1992; Preston et al., 1992) and that, taking a critical theory approach, of Laughlin and Broadbent (1993) who examined the impact of attempts to control particular organizations through the medium of the law. In a more general sense the discontinuities of history and the diverse roots of control systems are brought out by Miller and O’Leary (1987). Other work in this field has taken a more interpretive or anthropological approach, examining the role of values or culture in determining the extent to which it is possible to control organizational members. Ansari and Bell (1991) illustrate the effect of national culture; Broadbent (1992) and Dent (1991) focus in different ways on the impact of organizational cultures.

Overview

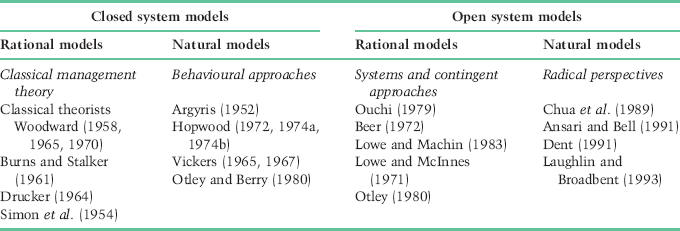

This retrospective review of the roots of management control provides the opportunity to reflect on its overall nature before moving forward to consider the prospects for the subject. It is clear that there is a wide range of research into the functioning of MCSs, even when its focus is narrowed to the more managerialist approach which we have adopted. A rough categorization of MCSs research work since 1965 set into this framework is given in Table B.1 and allows some reflection on the basic assumptions which underlie the work that has been undertaken.

Table B.1 Representative papers from four perspectives.

As mentioned earlier, whilst the framework developed by Scott provides a means by which to structure this review, it is important to note that every paper reviewed does not fit tidily into such a sequence. Further, it is clear that while practical theorists and scholars have developed ideas in new sectors of the diagram, this has not led to the abandonment of work in earlier sectors. The scientific management tradition is alive and well in areas such as operational research and in the consultancy world (e.g. in business process reengineering). The diversity of research approaches available is illustrated in the contents of the text Managerial Control, Theories Issues and Practices (Berry et al., 1995) as well as the special issue of the British Journal of Management on MCSs published in 1993 (September, Vol. 4, No. 3). Both these publications (plus the edited collections by Lowe and Machin, 1983 and Chua et al., 1989) have been spawned by the activities of the Management Control Association, a group of UK academics, which has sought for the past 20 years to promote wide-ranging research in the field. The latest review of nearly 20 research approaches is by Macintosh (1994), which unusually develops the issues through a selection of methodological approaches.

The predominant ontological stance is realist, stemming from the original concentration of the practical theorists on what they saw as real problems in practice. The primary epistemological stance of these control theorists is positivist and functionalist. Functionalist approaches have been severely criticized (e.g. Burrell and Morgan, 1979) as being part of the sociology (and perhaps the economy) of preservation, and thus antithetical to radical change. In the sense that management control is concerned with forms of stability this might be so, but the pursuit of efficiency has led to radical, and often unwelcome, change for many people, and control techniques have been used to promote quite radical social changes. Whilst some of the more radical theorists have examined this issue it, perhaps, remains somewhat under researched. Laughlin and Lowe (1990) using the framework of Burrell and Morgan (1979) along with Scott’s framework to review accounting research and demonstrate the diversity of approaches available argued that only the open systems approaches were beginning to move away from the functionalist orientation. Given our argument as to the paucity of open systems research, similar claims can be made for the need to extend the theoretical and methodological boundaries of management control research.2

The review shows that accounting still acts as an important element of management control. Whilst there have been developments in control in associated areas (such as Management Information Systems (MIS), human relations, operations research) these disciplines have been less inclined to see themselves as offering themselves as vehicles for integration of the diversity of organizational life than has accounting. Accounting is still seen as a pre-eminent technology by which to integrate diverse activities from strategy to operations and with which to render accountability. There is a sense in which the reduction of values to accounting measurements can contribute to management control sliding into the merely technical. Such a tendency is reinforced by the very constructs of the management information system and of information management which accounting uses. The ubiquity of computers, data capture, high-speed software, electronic data interchange and open access has changed the speed of data flow without yet having had great impact on either management control research or practice. Yet the topic of management control holds the promise of providing a powerful integrating idea to provide a very practical focus to concepts developed in other disciplines if it is not wholly accounting focused. Mills’ (1970) thoughts about the role of management control as an integrative teaching device also appear to apply with some force to its role as an integrative research framework for an important part of management studies. With this in mind we move to the final section.

Themes for Future Development

Here, we suggest some lines of enquiry which we believe it would be fruitful to pursue in developing research in management control. These are our own views, and we acknowledge we come to these issues from our own particular history and perspectives, thus running the risk of being both biased and incomplete. However, we believe they cover a wide-ranging agenda of important issues from both a practical and theoretical perspective. This prospective part of the paper flows from the retrospective review and is in two sub-sections. The first sub-section considers that the nature of the current environment and the needs this engenders are significantly different from those that determined and yet developed the earlier control approaches. The second sub-section considers the possibilities which could be available in the context of a broadening of the theoretical and methodological approaches adopted in research in the area.

The Environment of Control

The development of earlier MCSs theory took place in the context of large, hierarchically structured organizations. It centred upon accounting controls and developed measures of divisional performance, such as return on investment and residual income. It considered the issues raised in utilizing accounting performance measures to control large, diversified companies, in particular the construction of quasi-independent responsibility centres using systems of cost allocation and transfer pricing. The central theme was to produce measures of controllable performance against which managers could be held accountable, yet the empirical evidence (Merchant, 1987; Otley, 1990) suggests that the ‘controllability principle’ was more often honoured only in its breach. It can also be argued (see Otley, 1994) that changes in the business and social environment have led to the replacement of large integrated organizations by smaller and more focused organizational units, which require appropriate control mechanisms to be developed. Several features of the business environment seem to point towards a change in emphasis. A key trend is in the impact of uncertainty. It is a moot point whether uncertainty has increased, but it is true that the rate of change in both the commercial and governmental environment is rapid, requiring considerable adaptation on the part of organizations. Change appears to be affecting a much broader range of the population, whether it be technological, social or political change. The process of adaptation can no longer be left to a few senior managers who develop organizational strategies to be enacted by others; rather the process of change has become embedded in normal operating practices, and involves a wider range of organizational participants.

One consequence of this rapid rate of change has been encapsulated in ideas of global competition and ‘world class’ companies. As the rate of change increases, organizations need to devote more of their resources to adaptation and correspondingly less to managing current operations efficiently. One method of adaptation is planning, but this requires the prediction of the consequences of change, which is becoming more difficult; an alternative response is to develop the flexibility to adapt to the consequences of change as they become apparent. The ‘management of change’ remains an important managerial skill, but it should no longer be seen as a discrete event bounded by periods of stability; rather we are concerned with management in a context of continual change. This requires continual adaptation, a note which is reflected in the current popular terminology of ‘continuous improvement’.

A second feature has been a movement towards reducing the size of business units, certainly in terms of the number of people employed. In part, this has been driven by technological change, but there has also often been a strategic choice to encourage units to concentrate on their ‘core’ business and to avoid being distracted by irrelevant side issues. In turn, this has led to ‘non-core’ activities being outsourced, a process which can be most reliably undertaken in the context of long-term alliances. Such a trend is emphasized by just-in-time production and the processes of ‘market testing’ which have been imposed upon the public sector in the UK. The number of middle managers is being reduced and the range of responsibilities of those who remain is being increased. The split between strategic planning, management control and operational control, which was always tendentious has now become untenable, and a much closer integration between those functions has developed.

The boundaries of the organization and the boundaries of the control function are not necessarily co-terminus. Within the organization, ideas of ‘business process re-engineering’ have reinforced the need to devise control mechanisms that are horizontal (i.e. which follow the product or service through its production process until its delivery to the customer) rather than solely vertical (i.e. which follow the organizational hierarchy within organizational functions). As production processes are increasingly spread across legal boundaries (and often across national boundaries) new processes for the control of such embedded operations are needed (Berry, 1994). That is, control systems need to be devised which coordinate the total production and delivery process regardless of whether these processes are contained within a single (vertically integrated) organization or spread across a considerable number of (quasi-independent) organizations.

Traditional approaches to management control have been valuable in defining an important topic of study, but they have been predicated on a model of organizational functioning which has become increasingly outdated. This has resulted in the study of control systems becoming over narrow by remaining focused primarily upon accounting control mechanisms which are vertical rather than horizontal in their orientation. Contemporary organizations display flexibility, adaptation and continuous learning, both within and across organizational boundaries, but such characteristics are not encouraged by traditional systems. There is considerable anecdotal evidence to suggest that organizational practices are beginning to reflect these needs, so a key task for MCSs researchers is to observe and codify these developments.

In this type of changing environment the logic of systems theory could be argued to be of some importance in emphasizing issues such as the importance of environment and the holism of the organization. Although MCSs theory often makes references to the concepts of cybernetics, and sometimes to those of general systems theory, such approaches rarely inform empirical research work. Perhaps the most important contribution these disciplines can make is to broaden the horizons of management control researchers to include an appreciation of the overall context within which their work is located. The issues of the appropriate level of analysis, the definition of systems boundaries and the nature of systems goals deserve much more thorough attention. Even more importantly, the idea of control in an open system facing a complex and uncertain environment is also central for the design of effective systems to assist organizations to survive.

Current issues

Our suggestions here are seen partly as an attempt to raise important issues which appear under-researched at present and partly to promote the use of broader theoretical and methodological perspectives. Our argument is that the closed and functionalist perspective which still predominates needs to be extended.

We see the environment of control as changing, we also see it as of central importance and it is this to which we first turn. Although there have been attempts to broaden the scope of what is perceived as part of a control system (notably by Hopwood, 1974b, Merchant, 1985, and Lowe and Machin, 1983), a narrow financially biased perspective still dominates much of the control literature. The management literature has relatively recently emphasized ideas such as the balanced scorecard (predated by many years in France by the ‘tableau de bord’) where non-financial measures (e.g. customer, operations and innovation perspectives) are placed alongside traditional financial measures (Kaplan and Norton, 1992). The range of what is included as a management control is being extended with studies of performance-related pay, operational and process controls, and the whole issue of the management of corporate culture. However, studies of the overall practice of control, integrating the whole range of such functional controls, within particular organizations are still scarce. It should be clearly recognized that such attempts raise considerable methodological problems, of both a practical and theoretical nature. From a practical point of view, there is the issue of the extent to which a single researcher (or even a small team) can come to grips with such a wide range of practices in a sensible timescale. Such work would seem to be necessarily case study based, which raises issues of generalizability.

More fundamentally, it raises epistemological issues regarding the nature of theory in this field (Otley and Berry, 1994). It may well be that applied problem-solving methodologies are all that can be expected at high levels of resolution such as those necessary when observing practice within single organizations. Nevertheless, it is also our belief that the insight such attempts would provide would form an important basis for subsequent theoretical development. Another potentially fruitful approach is that of ‘middle range thinking’, as proposed by Laughlin (1995), which is both rooted in the critical tradition and strikes a balance between the notions of reality and subjectivity. This type of theory involves the use of skeletal frameworks which are then ‘fleshed out’ with empirical details of particular situations.

The recognition of the importance of the environment raises another important issue, the relationships across the boundary of what has traditionally been seen as the firm. Most of the management control literature has concentrated its attention at the level of the firm (or sub-units within it). There has been comparatively little exploration of control from a more macro or societal perspective. Although these issues have been addressed to some extent by the radical theorists, the ‘micro’ and the ‘macro’ have been seen as distinct areas. Despite the quite radical changes that have occurred in the UK environment over the past 15 years (not least due to the Thatcher government) the general issue has not been well explored in the control (as distinct from the economic) literature. In particular, the role of competition as a control mechanism is under-researched. Further, such institutional arrangements affect the legitimacy of different methods of control within organizations, such as the appropriate boundaries for managerial action and the role of consultation and participation amongst the work-force and these issues need fuller exploration. This also raises the issue of what have been called embedded organizations. We have already alluded to the fact that control systems increasingly operate across both the legal boundaries of firms and national boundaries. The needs of managing business processes in an extended supply and distribution chain that crosses many organizational boundaries raise challenging control issues. These have been explored to some extent in both the operations management and management information systems literature, and have surfaced in the popular management literature under the banner of ‘business process re-engineering’, but have yet to receive proper attention from an overall control framework. The open systems framework appears to be especially appropriate in this area.

We have also found very little research addressing the problems of control in multi-national and international organizations, in either the public or private sector. This is an issue that seems to have been given much more attention in the fields of strategy and marketing, than in control. Undoubtedly a complex field, issues as disparate as the impact of differing legal and institutional structures, financial and exchange control constraints, and the varied impact of national and corporate cultures all seem worthy of attention.

Wider fields also need to be addressed. The advent of environmental management and the attention now paid to ‘green’ issues has yet to impact on the control literature. However, the developing understanding of both human ecology (including issues of demography, population, ethnicity and religion) and physical ecology suggests that wider considerations need to be brought into the conceptualization of the problems of regulation and control of, and within, organizations. Clearly, these considerations raise new ethical issues for both control theorists and practitioners.

Gender issues in management control have received scant attention, despite an emerging set of questions about the extent to which there are ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ styles of managing. It may be that the language of management control needs reframing to encompass a wider range of possibilities. There is some support in the popular management literature for styles associated with the feminine gender stereo-type, such as empowerment, group or mutual accountabilities and upward appraisal. The whole concept of the learning organization suggests approaches to management which are more supportive than directive in their orientation. Numbers of women in the workforce continue to increase, although the ‘glass ceiling’ still exists. The implications of these changes on MCSs remain to be researched.

Conclusions

This paper extends previous reviews of the area of management control and provides some suggestions for further research. Our suggestions stem from the belief that the practice and researching of management control needs to recognize the environment in which organizations exist and to loosen the boundaries around the area of concern. We are also anxious to promote more critical research. Undoubtedly some of the narrowness of the research in the topic which we have highlighted is the result of our choice of definition of management control which remains rather managerialist in its focus. It is clear that the field of management control is of relevance to the practice of management but this should not preclude a critical stance and thus a broader choice of theoretical approaches.

The area is also under-researched, which might be explained by the nature of the methodologies required for its study and their unpopularity over the last 25 years especially in the US. This indicates a significant opportunity for contributions, offering a broader set of methodological stances, to be made in an important and developing field. In conclusion, we hope that this paper might play a small part in defining and developing management control as a coherent field of study within the management disciplines.

References

Amey, L. R. (1979). Budget Planning and Control Systems. Pitman, London.

Ansari, S. and J. Bell (1991). ‘Symbolism, Collectivism and Rationality in Organizational Control’, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, pp. 4–27.

Anthony, R. N. (1965). Planning and Control Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Division of Research, Harvard Business School, Boston.

Anthony, R. N., J. Dearden and N. M. Bedford (1984). Management Control Systems. Irwin, Homewood, IL.

Argyris, C. (1952). The Impact of Budgets on People. The Controllership Foundation, Ithaca, NY.

Ashby, W. R. (1956). An Introduction to Cybernetics. Chapman and Hall, London.

Babbage, C. (1832). On the Economy of Machinery and Manufacturers. Charles Knight, London.

Beer, S. (1972). Brain of the Firm. Allen Lane, Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Berry, A. J. (1994). ‘Spanning Traditional Boundaries: Organization and Control of Embedded Operations’, Leadership and Organisational Development Journal, pp. 4–10.

Berry, A. J., J. Broadbent and D. T. Otley (eds) (1995). Managerial Control: Theories, Issues and Practices. Macmillan, London.

Birnberg, J. G., L. Turopolec and S. M. Young (1983). ‘The Organizational Context of Accounting’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 111–129.

Boland, R. J. Jnr. and L. R. Pondy (1983). ‘Accounting in Organizations: A Union of Rational and Natural Perspectives’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 223–234.

Broadbent, J. (1992). ‘Change in Organisations: A Case Study of the Use of Accounting Information in the NHS’, British Accounting Review, pp. 343–367.

Bromwich, M. (1990). ‘The Case for Strategic Management Accounting: The Role of Accounting Information for Strategy in Competitive Markets’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 27–46.

Buckley, A. and E. McKenna (1972). ‘Budgetary Control and Business Behaviour’, Accounting and Business Research, pp. 137–150.

Burns, T. and G. M. Stalker (1961). The Management of Innovation. Tavistock, London.

Burrell, G. and G. Morgan (1979). Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis. Heinemann, London.

Checkland, P. B. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Wiley, Chichester.

Chua, W. F., T. Lowe and T. Puxty (1989). Critical Perspectives in Management Control. Macmillan, London.

Dent, J. F. (1991). ‘Accounting and Organizational Cultures: A Field Study of the Emergence of a New Organizational Reality’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 705–732.

Dirsmith, M. W. and S. F. Jablonsky (1979). ‘MBO, Political Rationality and Information Inductance’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 39–52.

Drucker, P. (1964). ‘Control, Controls and Management’. In: C. P. Bonini, R. K. Jaedieke and H. M. Wagner, Management Controls: New Directions in Basic Research, McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead.

Emmanuel, C. R. and D. T. Otley (1985). Accounting for Management Control. Van Nostrand Reinhold, Wokingham.

Emmanuel, C. R., D. T. Otley and K. Merchant (1990). Accounting, for Management Control (2nd edition). Chapman and Hall, London.

Ezzamel, M. and R. Watson (1993). ‘Organizational Form, Ownership Structure and Corporate Performance: A Contextual Empirical Analysis of UK Companies’, British Journal of Management, pp. 161–176.

Giglioni, G. B. and A. B. Bedeian (1974). ‘A Conspectus of Management Control Theory: 1900–1972’, Academy of Management Journal, pp. 292–305.

Govindarajan, V. and A. K. Gupta (1985). ‘Linking Control Systems to Business Unit Strategy: Impact on Performance’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 51–66.

Hirst, M. K. (1981). ‘Accounting Information and the Evaluation of Subordinate Performance: A Situational Approach’, Accounting Review, pp. 771–784.

Hofstede, G. H. (1968). The Game of Budget Control. Tavistock, London.

Hofstede, G. H. (1978). ‘The Poverty of Management Control Philosophy’, Academy of Management Review, July.

Hogler, R. L. and H. G. Hunt (1993). ‘Accounting and Conceptions of Control in the American Corporation’, British Journal of Management, pp. 177–190.

Hopwood, A. G. (1972). ‘An Empirical Study of the Role of Accounting Data in Performance Evaluation’, Supplement to Journal of Accounting Research, pp. 156–193.

Hopwood, A. G. (1974a). ‘Leadership Climate and the Use of Accounting Data in Performance Appraisal’, Accounting Review, pp. 485–495.

Hopwood, A. G. (1974b). Accounting and Human Behaviour. Prentice-Hall.

Johnson, P. and J. Gill (1993). Management Control and Organizational Behaviour. Paul Chapman, London.

Kaplan, R. S. (1983). ‘Measuring Manufacturing Performance: A New Challenge for Management Accountants’, Accounting Review, LVIII, pp. 686–705.

Kaplan, R. S. and D. P. Norton (1992). ‘The Balanced Scorecard – Measures that Drive Performance’, Harvard Business Review, Jan/Feb, pp. 71–79.

Laughlin, R. C. (1995). ‘Empirical Research in Accounting: A Case for Middle Range Thinking’, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability, pp. 63–87.

Laughlin, R. C. and J. Broadbent (1993). ‘Accounting and Law: Partners in the Juridification of the Public Sector in the UK?’, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, pp. 337–368.

Laughlin and Lowe (1990). ‘A Critical Analysis of Accounting Thought: Prognosis and Prospects for Understanding and Changing Accounting Systems Design’. In: D. J. Cooper, and T. M. Hopper (eds), Critical Accounts, Macmillan, London, pp. 15–43.

Lilienfeld, R. (1978). The Rise of Systems Theory: An Ideological Analysis. Wiley, New York.

Lowe, E. A. (1971). ‘On the Idea of a Management Control System: Integrating Accounting and Management Control’, Journal of Management Studies, pp. 1–12.

Lowe, E. A. and J. L. J. Machin (eds) (1983). New Perspectives in Management Control. Macmillan, London.

Lowe, E. A. and J. M. Mclnnes (1971). ‘Control in Socio-Economic Organizations: A Rationale for the Design of Management Control Systems (Section 1)’, Journal of Management Studies, pp. 213–227.

Lowe, E. A. and R. W. Shaw (1968). ‘An Analysis of Managerial Biasing: Evidence from a Company’s Budgeting Process’, Journal of Management Studies, pp. 304–315.

Machin, J. L. J. (1983). ‘Management control systems: whence and whither?’ pp. 22–42. In: E. A. Lowe and J. L. J. Machin (eds), New Perspectives in Management Control. Macmillan, London.

Macintosh, N. B. (1994). Management Accounting and Control Systems, An Organizational and Behavioural Approach. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester.

Merchant, K. A. (1985). Control in Business Organizations. Pitman, Boston.

Merchant, K. A. (1987). ‘How and Why Firms Disregard the Controllability Principle’. In: W. J. Bruns and R. Kaplan (eds), Accounting and Management: Field Study Perspectives. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Merchant, K. A. and R. Simons (1986). ‘Research and Control in Complex Organizations: An Overview’, Journal of Accounting Literature, pp. 183–203.

Miller, P. and T. O’Leary (1987). ‘Accounting and the Construction of the Governable Person’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 235–266.

Mills, A. E. (1970). ‘Management Controls and Integration at the Conceptual Level’, Journal of Management Studies, pp. 364–375.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The Nature of Managerial Work. Harper and Row, London.

Mintzberg, H. (1975). ‘The Managers Job: Folklore and Fact’, Harvard Business Review, pp. 49–61.

Otley, D. T. (1978). ‘Budget Use and Managerial Performance’, Journal of Accounting Research, pp. 122–149.

Otley, D. T. (1980). ‘The Contingency Theory of Management Accounting: Achievement and Prognosis’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 413–428.

Otley, D. T. (1983). ‘Concepts of Control: The Contribution of Cybernetics and Systems Theory to Management Control’. In: E. A. Lowe and J. L. J. Machin (eds), New Perspectives in Management Control. Macmillan, London.

Otley, D. T. (1990). ‘Issues in Accountability and Control: Some Observations from a Study of Colliery Accountability in the British Coal Corporation’, Management Accounting Research, pp. 91–165.

Otley, D. T. (1994). ‘Management Control in Contemporary Organizations: Towards a Wider Framework’, Management Accounting Research, pp. 289–299.

Otley, D. T. and A. J. Berry (1980). ‘Control, Organization and Accounting’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 231–244.

Otley, D. T. and A. J. Berry (1994). ‘Case Study Research in Management Accounting and Control’, Management Accounting Research, pp. 45–65.

Ouchi, W. G. (1979). ‘A Conceptual Framework for the Design of Organizational Control Systems’, Management Science, pp. 833–848.

Parker, L. D. (1986). Developing Control Concepts in the 20th Century. Garland, New York.

Perrow, C. (1970). Organizational Analysis: A Sociological View. Wadsworth, Belmont, California.

Prakash, P. and A. Rappaport (1977). ‘Information Inductance and its Significance for Accounting’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 29–38.

Preston, A. M. (1992). ‘The Birth of Clinical Accounting: A Study of the Emergence and Transformation of Discourses on Costs and Practices of Accounting in US Hospitals’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 63–100.

Preston, A. M., D. J. Cooper and R. W. Coombs (1992). ‘Fabricating Budgets: A Study of the Production of Management Budgeting in the NHS’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 561–594.

Rathe, A. W. (1960). ‘Management Controls in Business’. In: D. G. Malcolm and A. J. Rowe, Management Control Systems, Wiley, New York.

Rhaman, M. and A. M. McCosh (1976). ‘The Influence of Organizational and Personal Factors on the Use of Accounting Information: An Empirical Study’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 339–355.

Scott, W. R. (1981). ‘Developments in Organization Theory: 1960–1980’, American Behavioral Scientist, pp. 407–422.

Simmonds, K. (1981). ‘Strategic Management Accounting’, Management Accounting, 59(4), pp. 26–29.

Simon, H. A., G. Kozmetsky, H. Guetzkow and G. Tyndall (1954). Centralization vs. Decentralization in the Controller’s Department. Reprinted by Scholar’s Book Co., Houston (1978).

Simons, R. (1987). ‘Accounting Control Systems and Business Strategy: An Empirical Analysis’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 357–374.

Simons, R. (1990). ‘The Role of Management Control Systems in Creating Competitive Advantage: New Perspectives’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, pp. 127–143.

Simons, R. (1991). ‘Strategic Orientation and Top Management Attention to Control Systems’, Strategic Management Journal, pp. 49–62.

Simons, R. (1995). Levers of Control. Harvard Business School Press.

Thompson, J. D. (1967). Organizations in Action. McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead.

Tocher, K. D. (1970). ‘Control’, Operational Research Quarterly, pp. 159–180.

Vickers, G. (1965). The Art of Judgement: A Study of Policy-Making. Chapman and Hall, London.

Vickers, G. (1967). Towards a Sociology of Management. Chapman and Hall, London.

Weiner, N. (1948). Cybernetics. MIT Press. Cambridge, MA.

Wilson, B. (1984). Systems: Concepts, Methodologies and Applications. Wiley, Chichester.

Wisdom, J. O. (1956). ‘The Hypothesis of Cybernetics’, Yearbook for the Advancement of General Systems Theory, Vol. 1.

Woodward, J. (1958). Management and Technology. HMSO, London.

Woodward, J. (1965). Industrial Organization: Theory and Practice. Oxford University Press, London.

Woodward, J. and J. Rackham (1970). Industrial Organization: Behaviour and Control. Oxford University Press, London.

Wren, P. A. (1994). The Evolution of Management Thought (4th edition). Wiley, Chichester.

Endnotes

1. The authors recognize that this provides a narrow focus for the review, but space restraints preclude the possibility of providing a more comprehensive survey. Our choice has been, therefore, to restrict the survey to one which focuses on the literature which sees management control as a practical activity of managers. See pages S32–S33 for a discussion of the boundaries of our survey.

2. Agency theory research, not included in this review, would not be immune from this comment.