CHAPTER 4

Family fractures

Affluenza is a family problem. In a variety of ways, the disease is like a termite, undermining American family life, sometimes to the breaking point. We have already mentioned time pressures. Then, too, the pressure to keep up with the Joneses leads many families into debt and simmering conflicts over money matters that frequently result in divorce. Indeed, the American divorce rate, despite reaching a plateau in the 1980s and declining a bit since then, is still double what it was in the ’50s, and family counselors report that arguments about money are precipitating factors in 90 percent of divorce cases.1

But modern life in the Age of Affluenza affects marriage in more complex ways, spelled out clearly by the psychiatrists Jacqueline Olds and Richard Schwartz in their book The Lonely American. Longer working hours and the demands of caring for stuff require that parents find something to cut in their frenetically busy lives. What goes is time spent with friends and community members. Parents spend more time with their children today than a generation ago, though much of it consists of chauffeuring their children from one event to another, as Dr. William Doherty points out.

Doherty, a family therapist and professor at the University of Minnesota, warns that today’s kids are terribly overscheduled, as “market values have invaded the family.” Parents often see family life as about instilling competitive values in their children so they can achieve the best résumés to get into the best colleges to get the best jobs to earn the most money. Meanwhile, even though parents sacrifice a lot of personal time, including time for each other, to be with their kids, Doherty says the number of families that regularly eat dinner together or take vacations together has dropped by at least a third since 1970.2

Olds and Schwartz argue that, much of the time, only one parent is spending time with a child, leaving children with less chance to see how couples can effectively manage a marriage. And a greater focus on their children leaves most parents with less time to be alone together. Olds and Schwartz write that “even the most loving of couples can start to feel slightly estranged when they use up all their leisure time pursuing child-centered activities.”3 But by the same token, expectations of marriage are higher now, with spouses more likely to make greater demands on each other.

Worn out by work and childcare, parents depend more on each other to satisfy emotional needs, often spending more time at home, a process futurist Faith Popcorn called cocooning. Much of this time is spent in front of the TV—long-work-hour countries like the United States, Japan, and Korea have the highest rates of TV viewing; short-work-hour countries like the Netherlands and Norway have the least—because parents are more exhausted when they return home, and TV is the perfect activity for burned-out people since there is nothing to do but press the remote and be entertained.4 But the more TV viewing, the more people are exposed to television advertising and the hot zones of affluenza. “Chief among the obstacles” to a good family life, write Olds and Schwartz, is “the frenetic pace of the twenty-first-century workplace, and the length of the workday and workweek. It deprives people of time for social lives and it drains them of the energy to make those lives happen.”5

Olds and Schwartz say the time that gets squeezed in this arrangement is community time, which puts more strain on marriages. “Most couples now socialize less with family and friends and, consequently, receive less support from a wider social network,” they point out. A leading authority on the history of American families, Stephanie Coontz, agrees, arguing that the expectations couples place on each other threatens the institution of marriage and our social fabric as a whole. Until the modern era, Coontz reminds us, “most societies agreed that it was dangerously antisocial, even pathologically self-absorbed, to elevate marital affection and nuclear family ties above commitments to neighbors, extended kin, civic duty and religion.”6

While the American divorce rate has flattened in recent years, that is due in large part to fewer people being willing to make the commitment in the first place. Between 1950 and 2011, the marriage rate fell by two-thirds. In 2006, for the first time ever, more Americans households (50.3 percent) were headed by unmarried adults than married ones. Moreover, as Olds and Schwartz point out, more Americans are living alone than ever before. They suggest that this has led to elevated consumerism, as a single-occupancy household (unless part of a cohousing or other arrangement) must have its own set of appliances. This creates unintended environmental effects: single-person households use twice as many resources per capita as four-person households and 77 percent more energy per capita.7

But the trend toward solitary living has also resulted in an increase in loneliness. A Time magazine/AARP report in 2010 showed a near-doubling (from 20 to 35 percent) in the percentage of Americans over age forty-five that could be categorized as “chronically lonely” in the previous decade alone.8 These loners often consume more, as defensive purchases to mask their loneliness (or of pills—more than 60 percent of the world’s antidepressants are sold in the United States), but they are increasingly both unhappy and unhealthy.

Compared with other rich countries, the United States is a lousy place for families (with far fewer social supports), but perhaps it’s even worse for children. A 2013 UNICEF study, “The Welfare of Children in Rich Countries,” ranked the United States twenty-six out of twenty-nine nations surveyed, using criteria including child poverty, education levels, safety, risky behaviors, health, housing, and the environment.9 Only Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania fared worse. The top countries were all in Europe, led by the Netherlands, which ranked number one in several categories, followed by Sweden and other Nordic countries. Dutch children also ranked themselves as happiest, with US children coming in twenty-third in their assessment of their lives. What Dutch moms and dads—also rated as the world’s most satisfied parents—have is time for their kids and themselves. A majority work less than full time, yet their economic system allows them to live comfortably and securely, though more modestly than the average American.

We must concede that no system has been as effective as America’s generally unfettered free market in delivering the most goods at the lowest prices to consumers (think Wal-Mart). And in the Age of Affluenza, such success has become the supreme measure of value. But human beings are more than consumers, more than stomachs craving to be filled. We are producers as well, looking to express ourselves through stable, meaningful work. We are members of families and communities, moral beings with an interest in fairness and justice, living organisms dependent on a healthy and beautiful environment. We are parents and children.

Our affluenza-driven quest for maximum consumer access undermines these other values. To produce goods at the lowest prices, we are willing to lay off thousands of workers and transfer their workplaces from country to country in search of cheap labor. We shatter the dreams of those workers who are discarded, and often shatter their families as well. The security of whole communities is considered expendable. Lives are disrupted without a second thought. And as we shall see, children are pitted against parents, undermining family life even further.

CHILDHOOD AFFLUENZA

In 1969, when John was twenty-three, he taught briefly at a Navajo Indian boarding school in Shiprock, New Mexico. His third-grade students were among the poorest children in America, possessing little more than the clothes on their backs. The school had few toys or other sources of entertainment. Yet John never heard the children say they were bored. They were continually making up their own games. And though racism and alcoholism would likely scar their lives a few years later, they were, at the age of ten, happy and well-adjusted children.

That Christmas, John went home to visit his family. He remembers the scene, a floor full of packages under the tree. His own ten-year-old brother opened a dozen or so of them, quickly moving from one to the next. A few days later, John found his brother and a friend watching TV, the Christmas toys tossed aside in his brother’s bedroom. Both boys complained to John that they had nothing to do. “We’re bored,” they proclaimed. For John, it was a clear indication that children’s happiness doesn’t come from stuff. But powerful forces keep trying to convince America’s parents that it does.

THE CHILDREN’S MARKETING EXPLOSION

Spending by—and influenced by—American children recently began growing a torrid 20 percent a year and is expected to reach $1 trillion annually in the next few years. In 1984, kids four to twelve spent about $4 billion of their own money. By 2005, they spent $35 billion. Marketing to children has become the hottest trend in the advertising world.10

“Corporations are recognizing that the consumer lifestyle starts younger and younger,” explains Joan Chiaramonte, who does market research for the Roper Starch polling firm. “If you wait to reach children with your product until they’re eighteen years of age, you probably won’t capture them.”11

From 1980 to 2004 the amount spent on children’s advertising in America rose from $100 million to $15 billion a year, a staggering 15,000 percent! In her book, Born to Buy, Juliet Schor points out that children are now also used effectively by marketers to influence their parents’ purchases of big-ticket items, from luxury automobiles to resort vacations and even homes. One hotel chain sends promotional brochures to children who’ve stayed at its hotels, so the kids will pester their parents into returning. Schor points out that many American kids recognize logos by the age of eighteen months and ask for brand-name products at the age of two. The average child gets about seventy toys a year. For the first time in human history, children are getting most of their information from entities whose goal is to sell them something rather than from family, school, or religious groups. The average twelve-year-old in the United States spends forty-eight hours a week exposed to commercial messages. Yet American children spend only about forty minutes per week in meaningful conversation with their parents and less than thirty minutes of unstructured time outdoors. Susan Linn, the author of Consuming Kids, writes, “Comparing the advertising of two or three decades ago to the commercialism that permeates our children’s world is like comparing a BB gun to a smart bomb.”12

Children under seven are especially vulnerable to marketing messages. Research shows that they are unable to distinguish commercial motives from benign or benevolent motives. One ’70s study found that when asked who they would believe if their parents told them something was true and a TV character (even an animated one like Tony the Tiger) told them the opposite was true, most young children said they’d believe what the TV character told them. Both the American Psychological Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics say advertising targeting children is inherently deceptive.

What psychological, social, and cultural impacts are these trends having on children? A 1995 poll found that 95 percent of American adults worry that our children are becoming “too focused on buying and consuming things.” Two-thirds say their own children measure their self-worth by their possessions and are “spoiled.”13

VALUES IN CONFLICT

In Minneapolis, the psychologist David Walsh, author of Selling Out America’s Children, teaches parents ways to protect their offspring from falling captive to commercialism. After years spent treating so-called problem children, Walsh worries that childhood affluenza is reaching epidemic levels. He sees a fundamental collision of values between children’s needs and advertising. “Market-created values of selfishness, instant gratification, perpetual discontentment, and constant consumption have become diametrically opposed to the values most Americans want to teach their children,” says the grandfatherly Walsh, presenting his concerns with gentle passion.14

Today’s children are exposed to far more TV advertising than their parents were. The average child sees nearly 40,000 commercials a year, about 110 a day. In 1984, deregulation of children’s television by the Federal Trade Commission allowed TV shows and products to be marketed together as a package. Within a year, nine of the top ten best-selling toys were tied to TV shows.

But more importantly, perhaps, there’s a big difference between today’s ads and those of a generation ago. In the old ads, parents were portrayed as pillars of wisdom who both knew and wanted what was best for their children. Children, on the other hand, were full of wonder and innocence, and eager to please Mom and Dad. There was gender stereotyping—girls wanted dolls, and boys wanted cowboys and Indians—but rebelling against one’s parents wasn’t part of the message.

KIDS AS CATTLE

Now the message has changed. Marketers openly refer to parents as “gatekeepers,” whose efforts to protect their children from commercial pressures must be circumvented so that those children, in the rather chilling terms used by the marketers, can be “captured, owned, and branded.” At a 1996 marketing conference called Kid Power, held appropriately at Disney World, the keynote address, “Softening the Parental Veto,” was presented by the marketing director of McDonald’s.

Speaker after speaker revealed the strategy: Portray parents as fuddy-duddies who aren’t smart enough to realize their children’s need for the products being sold. It’s a proven technique for neutralizing parental influence in the marketer-child relationship.

Presenters at Kid Power ’96 further revealed how marketers now use children to design effective advertising campaigns. Kids are given cameras to photograph themselves and their friends to see how they dress and spend their time. They are observed at home, at school, in stores, and at public events. Their spending habits are carefully tracked. They are gathered into focus groups and asked to respond to commercials, separating the “cool” from the “uncool.”

The “coolest” contemporary ads frequently carry the message delivered by Kid Power ’96 speaker Paul Kurnit, a prominent marketing consultant, as seen in the Affluenza documentary. “Antisocial behavior in pursuit of a product is a good thing,” Kurnit stated calmly, suggesting that advertisers could best reach children by encouraging rude, often aggressive behavior and faux rebellion against the strictures of family discipline. There is, some critics say, a serious danger in this: If rude, aggressive behavior becomes the norm for children as they emulate advertising models, to what level will children have to escalate their aggressive activities to really feel they are rebelling?

BETTER THAN STRAIGHT A’S

In the Age of Affluenza, voters demand tax cuts and reductions in public spending as their personal spending habits leave them with growing credit debt. Then, too, more and more affluent families are sending their children to private schools, further reducing voter support for public school systems.

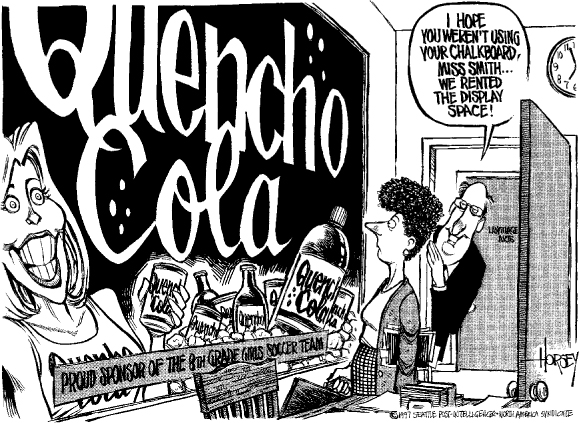

As funding for education tightens, school boards all across America have turned to corporations for financial help. In exchange for cash, companies are allowed to advertise their products on school rooftops, hallways, readerboards, book covers, uniforms, and buses.

“Children in our society are seen as cash crops to be harvested,” explains Alex Molnar, a professor of education at the University of Colorado who has been investigating commercialism in the schools for many years. Angry and passionate, Molnar readily displays his collection of “curriculum materials” created by corporations for use in the public schools.

In one, students find out about self-esteem by discussing “Good and Bad Hair Days” with materials provided by Revlon. In others, they learn to “wipe out that germ” with Lysol, and they study geothermal energy by eating “Gusher’s Fruit Snacks” (the “teachers’ guide” suggests that each student should get a gusher, bite into it, and compare the sensation to a volcanic eruption!). They also learn the history of Tootsie Rolls, make shoes for Nike as an environmental lesson, count Lay’s potato chips in math class, and find out why the Exxon Valdez oil spill wasn’t really harmful at all (materials courtesy of—you guessed it—Exxon) and why clear-cutting is beneficial—with a little help from Georgia-Pacific.

Fortunately, a parent-teacher backlash is emerging in a few communities. In late 2001, the Seattle School Board voted to create an anticommercial policy, but Molnar points out that today, many more states allowing advertising on the sides of school buses, a revenue generator first pioneered in Colorado Springs in the early 1990s.15

CAPTIVE KIDS

As affluenza becomes an airwave-borne childhood epidemic, America’s children pay a high price. Not only does their lifestyle undermine our children’s physical health, but their mental health seems to suffer too. Psychologists report constantly rising rates of teenage depression and thoughts about suicide, and a tripling of actual child suicide rates since the 1960s.16

Some of this stems from the overscheduling of children to prepare them for our adult world of consumerism, workaholism, and intense competition. This can reach truly ridiculous levels. Since the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, nearly 20 percent of American school districts have banned recess for elementary school children. The idea, as one Tacoma, Washington, school administrator put it, is to “maximize instruction time to prepare the children to compete in the global economy.” This is nuts. We’re talking second graders here.

Kate Cashman, a humor columnist, wondered if we didn’t have it backward. At a time of rising childhood obesity, we’re getting rid of recess while inviting junk food into our schools. She suggested we reverse that—more recess, less junk food. She’d call her policy the “No Child Left with a Fat Behind Act.” Sign us up to lobby in favor of the act. Let’s try to get it passed in every state! It may sound silly, but it makes far more sense than most of the legislation that’s out there these days.

What kind of values do our children learn from their exposure to affluenza? In a recent poll, 93 percent of teenage girls cited shopping as their favorite activity. Fewer than 5 percent listed “helping others.” In 1967, two-thirds of American college students said “developing a meaningful philosophy of life” was very important to them, while fewer than one-third said the same about “making a lot of money.” By 1997, those figures were reversed.17 A 2004 poll at UCLA found that entering freshman ranked becoming “very well off financially” ahead of all other goals. Juliet Schor surveyed children aged ten to thirteen for their responses to the statement, “I want to make a lot of money when I grow up.” Of those children, 63 percent agreed; only 7 percent thought otherwise.

Jacqueline Olds and Richard Schwartz point out that a questionnaire called the Narcissistic Personality Inventory finds a 30 percent increase in self-centeredness among students, with more than two-thirds now scoring above what the average was in 1982, when the survey began. “There is no other example in empirical psychology research of personality changing as rapidly and dramatically,” they warn.18 What does this bode for our future?

FAMILY VALUES OR MARKET VALUES?

Concerns about the impact of market values and affluenza on family life have come primarily from the liberal end of the American political spectrum. But some conservatives have also begun to look carefully at what they see as an inherent tension between market values and family values. Edward Luttwak, a former Reagan administration adviser and the author of the critically acclaimed book Turbo-Capitalism, expressed his concerns about the issue rather bluntly: “The contradiction between wanting rapid economic growth and dynamic economic change and at the same time wanting family values, community values, and stability is a contradiction so huge that it can only last because of an aggressive refusal to think about it.”19

Calling himself “a real conservative, not a phony conservative,” Luttwak says, “I want to conserve family, community, nature. Conservatism should not be about the market, about money. It should be about conserving things, not burning them up in the name of greed.”

Too often, he says, so-called conservatives make speeches lauding the unrestricted market (as the best mechanism for rapidly increasing America’s wealth), while at the same time saying “we have to go back to old family values; we have to maintain communities.” “It’s a complete non sequitur, a complete contradiction; the two of course are completely in collision. It’s the funniest after-dinner speech in America. And the fact that this is listened to without peals of laughter is a real problem.”

“America,” Luttwak contends, “is relatively rich. Even Americans that are not doing that well are relatively rich, but America is very short of social tranquillity; it’s very short of stability. It’s like somebody who has seventeen ties and no shoes buying himself another tie. The US has no shoes as far as tranquillity and the security of people’s lives is concerned. But it has a lot of money. We have gone over to being a complete consumer society, a 100 percent consumer society. And the consequences are just as one would predict them: mainly lots of consumption, lots of goodies and cheap things, cheap flights, and a lot of dissatisfaction.”20