CHAPTER 23

Policy prescriptions

Despite thirty-five years of collective bad-mouthing that has left the American public deeply cynical about whether government can ever do anything right, we believe it can play an important role in helping create a society that is affluenza unfriendly, or, to put it in more positive terms, simplicity friendly. We line up squarely on the side of those who say our social ills won’t be cured by personal action alone. Just as the symptoms of affluenza are many and interconnected, so must be public efforts to quarantine it. There is no silver bullet that by itself will do the trick. It will take a comprehensive strategy, at all levels of government from local to federal, around several key areas of action:

• A reduction in annual working hours

• A restructuring of the tax and earnings systems

• Corporate reform that includes responsibility for entire product cycles

• Investment in a sustainable infrastructure

• Redirection of government subsidies

• A new concept of child protection

• Campaign finance reform

• And, finally, new ideas about economic growth

BACK TO THE ROAD NOT TAKEN

First of all, if we want to put a lid on the further spread of affluenza, we should restore a social project that topped organized labor’s agenda for half a century, then suddenly fell from grace.

In chapter 13 we argued that since World War II, Americans have been offered what economist Juliet Schor calls “a remarkable choice.” As our productivity more than doubled, we could have chosen to work half as much—or even less—and still produce the same material lifestyle we found “affluent” in the ’50s. We could have split the difference, letting our material aspirations rise somewhat but also taking an important portion of our productivity gains in the form of more free time. Instead, we put all our apples into making and consuming more.

Established as law in 1938, the forty-hour workweek is still our standard (though most full-time American workers average closer to 45 hours a week). By law, we could set a different standard, and we should. It need not be a one-size-fits-all standard, like a thirty-hour week of six-hour days as proposed in the 1930s (and more recently in a 1993 congressional bill written by Democratic representative Lucien Blackwell of Pennsylvania) or a thirty-two-hour week composed of four eight-hour days, though for many working Americans either of those choices would be ideal.

More important, perhaps, is to get annual working hours—now averaging about 1,800 per year and exceeding those even of the workaholic Japanese—under control. Were the average workday to be six hours, we’d be putting in less than 1,500 hours a year, the norm in several western Europe nations. That’s an additional 300 hours—seven and half weeks!—of free time. So here’s a suggestion: Set a standard working year of 1,500 hours for full time, keeping the forty-hour a week maximum. Then allow workers to find flexible ways to fill the 1,500 hours.

FLEXIBLE WORK REDUCTION

Polls have shown that half of all American workers would accept a commensurate cut in pay in return for shorter working hours.1 But the cut needn’t be based on a one-to-one ratio. Workers are more productive per hour when they work fewer hours. Absenteeism is reduced and health improves. Therefore, as W. K. Kellogg recognized in the 1930s, their thirty-hour weeks should be worth at least thirty-five hours’ pay and perhaps more. In fact, in the 1990s, Ron Healey, a business consultant in Indianapolis, persuaded several local industries to adopt what he calls the “30-40 now” plan. They offer prospective employees a normal forty-hour salary for a thirty-hour week. Increased employee productivity made the experiment successful for most.

THE “TAKE BACK YOUR TIME” CAMPAIGN

But to combat affluenza, we ought not fear trading income for free time. Beyond the reduction to 1,500 hours per year, legislation could ensure the right of workers to choose further reductions in working hours—instead of increased pay—when productivity rises, or further reductions in working hours at reduced pay, when productivity is stagnant.

In the short run, we need immediate legislation to provide time protections for American workers that resemble those that virtually every other industrial nation takes for granted:

• Paid childbirth leave for all parents. Today, only 40 percent of Americans are able to take advantage of the twelve weeks of unpaid leave provided by the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993.

• At least one week of paid sick leave for all workers. Many Americans work while sick, lowering productivity and endangering other workers.

• At least three weeks of paid annual vacation for all workers. Studies show that 26 percent of American workers receive no paid vacation at all.

• A limit on the amount of compulsory overtime work that an employer can impose, with the goal being to give employees the right to accept or refuse overtime work.

• Hourly wage parity and protection of promotions and prorated benefits for part-time workers.2

FALLING BEHIND THE REST OF THE WORLD

Back in July 2004, during an appearance on PBS’s NOW with David Brancaccio, the Republican pollster and strategist Frank Luntz observed that a majority of “swing” voters were working women with young children. Luntz said his focus groups revealed that “lack of free time” is the number one issue with these voters. “The issue of time matters to them more than anything else in life,” Luntz declared.

Yet President George W. Bush only paid lip-service to the issue, commenting about it in his speeches but offering no real solutions. And John Kerry, the Democratic candidate, failed to address it at all. The same was true of Barack Obama and his opponents. “Shut up and work overtime” seems to be the message from American politicians of both major parties.

American public policies protecting our family and personal time fall far short of those in other countries. A study released by the Harvard School of Public Health, covering 168 of the world’s nations, concluded that “the United States lags dramatically behind all high-income countries, as well as many middle- and low-income countries when it comes to public policies designed to guarantee adequate working conditions for families.”3 The study found that:

• 163 of 168 countries guarantee paid leave for mothers in connection with childbirth. 45 countries offer such leave to fathers. The United States does neither.

• 139 countries guarantee paid sick leave. The US does not.

• 96 countries guarantee paid annual (vacation) leave. The US does not.

• 84 countries have laws that fix a maximum limit on the workweek. The US does not.

• 37 countries guarantee parents paid time off when children are sick. The US does not.

WORK SHARING AND WORK REDUCTION

Plans for spreading work around by shortening hours should begin now for another reason: When the next recession does come, will we simply say “tough luck” to those whose jobs are lost? There is a better way. Say a company needs to reduce production by 20 percent and believes it must lay off one-fifth of its work-force. What if, instead, it cut everybody’s workweek by one day? We predict that most people would soon love the time off. We have some empirical evidence for this.

Public employees in Amador County, California, were outraged when their hours and pay were cut at the height of the Great Recession, but two years later, 71 percent of them voted to keep their shorter schedules despite the pay cut. With its timbered ridges and deep canyons extending to the snowy wilderness of the Sierra Nevada, Amador County, population 38,000, lies in the heart of California’s “gold rush” country. It’s decidedly conservative; no Democratic presidential candidate has carried the county since Jimmy Carter in 1976. John McCain won nearly 60 percent of the Amador vote in 2008.

Like the rest of California, Amador was hurting in 2009. The state, seeking to eliminate its $35 billion budget deficit, cut back on social service support for its counties, and Amador had to find a way to cope with less. Conservative county supervisors limited all but essential employees to a four-day week. Workers were to report Monday through Thursday for nine hours each day. County offices would be closed on Fridays. Salaries would be cut by 10 percent, commensurate with a 10 percent reduction in work hours.

When word of the change came down, the workers, and SEIU 1021, the union that represents them, were livid. Like other public employees, they had already made key concessions in recent years and, justifiably, felt their family budgets were severely strained. “The cut meant a lot of money for a lot of people,” said one Amador County program manager, who asked to remain anonymous (the issue still generates animosity among some workers). “Then there were the questions like, ‘How can we get the work done in four days?’”

But despite the workers’ protests, the county argued that otherwise it would have to lay off workers, and county supervisors were adamant that they didn’t want layoffs. Angry, but understanding the need to preserve jobs, union leaders agreed to the arrangement—but for only two years. So in 2011, county workers were given a choice of sticking with four-day shifts or returning to a five-day week with a pay increase and losing some of their colleagues to layoffs. Without directly consulting its members again, the union chose the five-day week. In June, the remaining employees started working Fridays again. Amador County cut 17 workers to balance its budget.

The remaining workers were glad to be getting higher pay again, but many soon had second thoughts. Quite a few were unhappy because they had been enjoying their four-day weeks. Some went fishing or camping over the long weekends; outdoor activities are popular in this rural county. “I was at first very concerned about losing the 10 percent,” one worker told John, “but I found that I could make it work without a huge hardship. And I found that what I gained in time actually outweighed what I lost in money.” Then too, many of the workers sympathized deeply with their union brothers and sisters who’d lost their jobs. They pressured SEIU for a vote that might restore the four-day week.

In August, the union polled its members. Of the 178 workers (nearly the entire work force) who voted, 71 percent (126) chose to return to the shorter week, even with less pay. Only 29 percent (52) wanted to keep the longer workweek. A month later, county employees returned to a four-day, 36-hour schedule. Sixteen of the seventeen laid-off workers were rehired. It’s not perfect, one worker told John. The work must now be accomplished in less time. “A lot of folks still come in for a bit on Fridays,” she reports. But she still believes that, on balance, most people feel the trade-off is worth it.4

With both parents in a majority of families working full time these days, weekends in America have become “workends” for most couples. For many Amador parents, the four-day week changed that. “The Fridays off gave me a chance to run errands and get chores done while my kids were at school, and that lets my weekend be a weekend,” one observed. “Before, it felt like I had only one day off a week that was really for pleasure. Now I’ve got the whole weekend. It helps. It’s nice to have this balance in terms of your family life and your sanity.”

The Amador County story deserves closer attention from researchers. It’s highly conceivable that the extra day off has relieved stress and improved family life for many workers. It may also be reflected in better health outcomes. We need studies to understand whether or not this is the case, since it might also be possible that nine-hour days and faster work schedules have negated any of these possible gains. It seems a valuable university research project. But in any case, we do know that the reduced schedule has been popular with many workers.

GOING DUTCH

It’s unfortunate that the Amador case study involved a compulsory reduction of hours. But many agencies, nonprofits, and businesses might want to offer more opportunities for shorter hours with reduced pay (but job security and benefits), as in Europe. In the Netherlands, under the Hours Adjustment Act of 2000, workers are allowed to downsize their hours, while keeping the same hourly pay, full health care, and prorated benefits. Unless employers can prove a serious financial hardship for their firms, they must grant the request for shorter hours. More than 95 percent of requests are approved. Consequently, the Dutch now have the highest percentage of part-time workers and shortest working hours in the world. They also have among the highest levels of labor force participation, low unemployment, and among the highest levels of confidence among workers that they can find another job if they lose theirs.5

In the United States, a similar policy could allow those who want to work less to cut back, opening space for others who simply want to work. As early adapters experiment with these new schedules and find them to their liking, word will spread and other workers will follow. The Gallup daily happiness poll shows that Americans are 20 percent happier on weekends than on workdays. Finding ways to offer longer weekends for American workers, who work some of the longest hours in the industrial world, ought to be part of the progressive agenda. Happiness science shows that people don’t always know what will make them happy; consequently, they tend to choose money over time. But an experience of more time and the life satisfaction that flows from it can change that attitude. It’s a lesson that has been confirmed for many in Amador County. Amador is only a microcosm and a very small step up a big mountain of overwork and consumerist values. But mountains are conquered by single steps.

REMOVING THE BIG OBSTACLE TO WORK SHARING

Of course, one additional public policy change would help make work sharing possible. It is single-payer health care, which would relieve the cost of health care provision for American employers. Because health care is so expensive, businesses find it more cost-effective to hire fewer workers and work them longer rather than pay benefits for more employees. The cost of employer-financed health care is the single most important factor in reducing the international competitiveness of American firms.

With a single-payer system, Canada manages to cover all its citizens at a total cost per person that is far less than what we spend in the United States. Despite criticisms of the Canadian system by US politicians, Canadians are healthier and live longer than their neighbors. And Canadians are so fond of their health care system that a nationwide poll to determine “the greatest Canadian of all time,” done by the Canadian Broadcasting Company, ended up bestowing the honor on Tommy Douglas. Douglas, the late Socialist premier of Saskatchewan, was chosen, according to those who voted for him, because he was the father of the Canadian health care system (he was also the grandfather of American actor Kiefer Sutherland, though that probably didn’t affect the polling much).6

In any case, many Americans now work much longer than is healthy just to keep their health benefits, a problem that a public single-payer system would solve.

RETIRING STEP BY STEP

There are other ways of exchanging money for time. Many academics receive sabbaticals, anything from a quarter to a year off every several years, usually accepting a reduced salary during the period. Why not a system of sabbaticals every seven to ten years for all workers who are willing to take moderate salary reductions when they are on sabbatical? We all need to recharge our batteries every so often.

Or how about a system of graduated retirement? For many of us, self-esteem takes a hit and boredom a bounce when we suddenly go from forty-hour weeks to zero upon retiring. Instead, we could design a pension and social security system that would allow us to retire gradually. Let’s say that at fifty years of age we cut 300 hours from our work year—nearly eight weeks. Then at fifty-five we cut 300 more. At sixty, 300 more. And at sixty-five, 300 more. Now, we’re down to 800 (given no change in the present annual pattern). We might then have the option to stop paid labor entirely, or to keep working 800 hours a year for as long as we are capable.

What this would do is allow us to begin learning to appreciate leisure, volunteer more, and broaden our minds long before final retirement. It would allow more young workers to find positions and allow older workers to stay on longer to mentor them. It would allow older workers to both stay involved with their careers and also find time for more balance in their lives.

A variation on this idea is to allow workers to take some of their “early retirement” at different stages of their careers, perhaps when they need more parenting time, for example. The ultimate idea, promoted in some European countries, is that a certain number of hours would constitute a total paid work life, with considerable flexibility around when the hours are worked.

TAXES

A change in the tax system, similar to one already under way in parts of Europe, could also help contain affluenza. The first step toward a change could come through an idea called the progressive consumption tax. Proposed by the economist Robert Frank in his book Luxury Fever, the tax would replace the personal income tax. Instead, people would be taxed on what they consume, at a rate rising from 20 percent (on annual spending under $40,000) to 70 percent (on annual spending over $500,000). Basically the idea is to tax those with the most serious cases of “luxury fever” (which seems to be Frank’s synonym for affluenza) at the highest rates, thus encouraging saving instead of spending.7

At the same time, we must make it possible for lower-income Americans to meet their basic needs without working several jobs. The old Catholic idea of a family, or living (we prefer the term livable), wage, championed by Pope Leo XIII in his 1891 Encyclical Rerum Novarum, could be accomplished by a negative income tax or tax credits that guarantee all citizens a simple but sufficient standard of living above the poverty line.

But the solution also includes a dramatic increase in a minimum wage that has languished in America and now buys less than it did in 1968. President Obama has talked of raising the minimum wage to $9 an hour. This would only be about half that in very successful Nordic economies and Australia, where minimum wages average $17 an hour. Given somewhat higher prices in these countries, that comes out to less—about $14 or $15—in actual buying power, but it allows minimum-wage workers to support themselves adequately without being mired in poverty. When John asked a McDonald’s cashier in Melbourne, Australia, if she actually made the minimum wage of $17 an hour, she replied that she had started at that but was now up to about $18.50.

Granted, to avoid huge economic dislocations, this much higher minimum wage would need to be phased in, but not at the current glacial rate of change. Arguments by conservatives that raising the minimum wage decreases the number of jobs have been consistently shown to be false; indeed, as the multimillionaire Nick Hanauer points out, raises at the bottom of the economy keep it strong, not greater tax cuts for people like himself. Fighting affluenza is not just about the consuming less; it’s also about fairness. Some Americans have called for a “maximum wage,” an idea first broached by Saint Augustine many hundreds of years ago. We may or may not need that; strong consumption and luxury taxes could substitute. The point is to do all we can to make our economy fairer. Often, it is the poorest victims of affluenza who are accused of being spendthrifts and living beyond their means while the real luxury spenders get a pass.

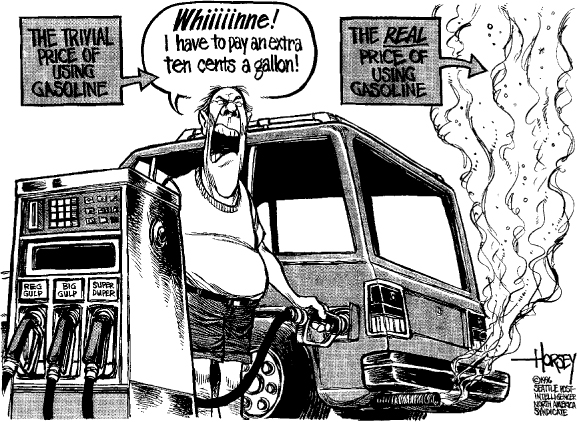

Equally promising are so-called green taxes. Their proponents would replace a portion of taxes on “goods” such as income—and payroll taxes, which discourage increased employment—with taxes on “bads” such as pollution or waste of nonrenewable resources. The point would be to make the market reflect the true costs of our purchases. We’d pay much more to drive a gas guzzler, for example, and a little more for this book (to cover the true costs of paper), but no more for a music lesson or theater ticket.

Additional carbon taxes would discourage the burning of fossil fuels. Pollution taxes would discourage the contamination of water and air. The costs of cleaning up pollution would be added as a tax on goods whose production causes it. Such a tax could make organic foods as cheap as pesticide-laced produce. Depletion taxes would increase the price of nonrenewable resources and lower the comparative price of goods made to last.

While such a green tax system would be complicated, it could go a long way toward discouraging environmentally or socially harmful consumption, while encouraging benign alternatives. As things currently stand, we more often subsidize what we should be taxing—extractive industries like mining (as much as $3 billion in subsidies a year), and air and auto travel, for example.8 We could, and should, turn that around, subsidizing clean technologies and activities like wind and solar power or organic family farms instead of oil and agribusiness.

CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY

Another way to reduce the impact of consumption is to require corporations to take full responsibility for the entire life cycle of their products, an idea now gaining widespread acceptance in Europe. The concept is simple, and well-explained in the book Natural Capitalism, by Paul Hawken and Amory and Hunter Lovins.9 In effect, companies would no longer sell us products but lease them. Then, when the products reach the end of their useful lives, the same companies would take them back to reuse and recycle them, saving precious resources.

STOPPING CHILD ABUSE

The consumer advocate Ralph Nader has called the recent upsurge in marketing that targets children a form of “corporate child abuse.” It’s as if marketers have set out knowingly to infect our children with affluenza by spreading the virus everywhere kids congregate. It’s time to protect our kids. At a minimum, we can keep commercialism out of our schools. Second, we can begin to restrict television advertising to children. Already, places like Sweden and the province of Quebec don’t allow it. If you’re a parent, you probably long for relief from TV advertising’s manipulation of your kids. Moreover, a stiff tax on all advertising would send a strong message to corporate America that curbing the spread of affluenza is serious business.

CAMPAIGN FINANCE REFORM

There are, of course, dozens of other good anti-affluenza legislative ideas out there and no space to mention them here, but none will come to fruition as long as those who profit most from affluenza pull the strings in our political system. The sheer cost of elections—a single New Jersey Senate race in 2000 resulted in $100 million in spending—leaves candidates beholden to those who pay, and those who pay are those who have money and want to keep it.

So anti-affluenza legislation has to include campaign finance reform (including an amendment overturning the disastrous Citizens United Supreme Court decision that allowed much greater corporate contributions to campaigns), taking the PACs out of politics, and offering competing candidates equal media time to present their ideas but no time for clever yet meaningless thirty-second commercials. Former Texas agriculture commissioner Jim Hightower has it right. “The water won’t clear up,” he says, “until you get the hogs out of the creek.”10

BUT WON’T OUR ECONOMY COLLAPSE?

What if Americans started buying smaller, more fuel-efficient cars, driving them less and keeping them longer? What if we took fewer long-distance vacations? What if we simplified our lives, spent less money, bought less stuff, worked less, and enjoyed more leisure time? What if government began to reward thrift and punish waste, legislated shorter work hours, and taxed advertisers? What if we made consumers and corporations pay the real costs of their products? What would happen to our economy? Would it collapse, as some economists suggest?

Truthfully, we don’t know exactly, since no major industrial nation has yet embarked on such a journey. But there’s plenty of reason to suspect that the road will be passable if bumpy at first, and smoother later. If we continue on the current freeway, however, we’ll find out it ends like Oakland’s Interstate 880 during the 1989 earthquake—impassable and in ruins.

Surely we can’t deny that if every American took up voluntary simplicity tomorrow, massive economic disruption would result. But that won’t happen. A shift away from affluenza, if we’re lucky enough to witness one, will come gradually, over a generation perhaps. Economic growth, as measured by the gross domestic product, will slow down and might even become negative. But as the economist Juliet Schor points out, there are many European countries (including Holland, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway) whose economies have grown far more slowly than ours, yet whose quality of life—measured by many of the indicators we say we want, including free time, citizen participation, lower crime, greater job security, income equality, and health—is higher than our own.11 Gallup also finds that they are the world’s happiest countries.

You might think of them as the world’s first “postconsumer” societies. Their emphasis on balancing growth with sustainability is widely accepted across the political spectrum. As former Dutch prime minister Ruud Lubbers, a conservative, put it:

It is true that the Dutch are not aiming to maximize gross national product per capita. Rather, we are seeking to attain a high quality of life, a just, participatory and sustainable society. While the Dutch economy is very efficient per working hour, the numbers of working hours per citizen are rather limited. We like it that way. Needless to say, there is more room for all those important aspects of our lives that are not part of our jobs, for which we are not paid and for which there is never enough time.12

These postconsumer economies show no sign of collapse—instead, the recent European economic crisis has been hardest on the very countries (Spain, Ireland, Greece, Iceland) that followed the US model of tax cutting, financial deregulation, longer working hours, housing speculation, and privatization to increase growth.

TIME FOR AN ATTITUDE ADJUSTMENT

If anti-affluenza legislation leads to slower rates of economic growth or a “steady state” economy that does not grow at all, so be it (as we argue in the next chapter, growth of GDP is a poor measure of social health anyway). Beating the affluenza bug will also lead to less stress, more leisure time, better health, and longer lives. It will offer more time for family, friends, and community. And it will lead to less traffic, less road rage, less noise, less pollution, and a kinder, gentler, more meaningful way of life.

In a ’60s TV commercial, an actor claims that Kool cigarettes are “as cool and clean as a breath of fresh air.” We watch that commercial today and can’t keep a straight face, but when it first aired, nobody laughed. Since that time, we’ve come to understand that cigarettes are silent killers. We’ve banned TV ads for them. We tax them severely, limit smoking areas, and seek to make tobacco companies pay the full costs of the damage cigarettes cause. We once thought them sexy, but today most of us think they’re gross.

Where smoking is concerned, our attitudes have certainly changed. Now, with growing evidence that affluenza is also hazardous, it’s surely time for another attitude adjustment.