CHAPTER 14

An emerging epidemic

How little, from the resources unrenewable by Man, cost the things of greatest value—wild beauty, peace, health and love, music and all the testaments of spirit! How simple our basic needs—a little food, sun, air, water, shelter, warmth, and sleep! How lightly might this earth bear Man forever!

—NANCY NEWHALL AND ANSEL ADAMS,

This Is the American Earth, 1960

During World War II, Americans accepted rationing and material deprivation. Wasteful consumption was out of the question. In every city, citizens gathered scrap metal to contribute to the war effort. Most grew some of their own food, in so-called victory gardens. Driving was limited to save fuel. Despite the sacrifices, what many older Americans remember most from that time was the sense of community, of sharing for the common good and uniting to defeat a common enemy.

But shortly after World War II ended, pent-up economic demand in the form of personal savings, coupled with low-interest government loans and mushrooming private credit, led to a consumer boom unparalleled in history. The GI Bill sparked massive construction of housing at the edge of America’s cities, beginning with the famous Levittown development on Long Island. The average size of a Levittown bungalow was only 750 square feet, but its popularity encouraged other developers to build sprawling suburbs with larger homes.

New families filled the new homes as the baby boom began. Each family needed lots of appliances and—with transit service in the suburbs nonexistent—cars to get around. It’s fascinating to watch the many corporate and government films produced during that period, both documenting and extolling the new mass consumption society.

THE GOODS LIFE

“The new automobiles stream from the factories,” the narrator cheers, in one late-forties film. “Fresh buying power floods into all the stores of every community. Prosperity greater than history has ever known.” In the same film, we see a montage of shots of people spending money and hear more peppy narration: “The pleasure of buying, the spreading of money! And the enjoyment of all the things that paychecks can buy are making happy all the thousands of families!” Utopia had arrived!

Another film proclaims that “we live in an age of growing abundance” and urges Americans to give thanks for “our liberty to buy whatever each of us may choose” (the words come with a heavenly chorus humming “America the Beautiful” and shots of the Statue of Liberty). A third reminds us that “the basic freedom of the American people is the freedom of individual choice” (of which products to purchase, of course).

One film appeals to women to take up where the soldiers of World War II left off and fight “the age-old battle for beauty.” We’ve been told “you can’t buy beauty in a jar,” the narrator says, “but that old adage is bunk. We have the money to spend and we want all the lovely-smelling lotions, soaps, and glamour goo we can get with it.” Joy in a jar. As women try on perfumes in an upscale department store, the narrator continues: “Our egos are best nourished by a well-placed investment in real luxury goods—what you might call discreetly conspicuous waste.” “Waste not, want not,” Benjamin Franklin once admonished, but the new slogan might have been “waste more, want more.” Almost overnight, the good life became the goods life.

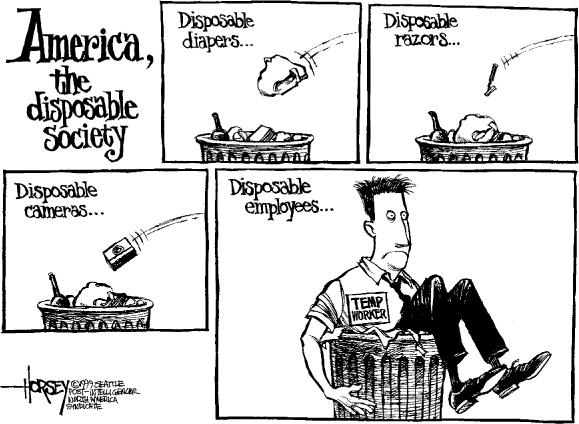

PLANNED OBSOLESCENCE

“The immediate postwar period does represent a huge change in the kinds of attitudes that Americans have had about consumption,” says the historian Susan Strasser, author of Satisfaction Guaranteed.1 “Discreetly conspicuous waste” got another boost from what marketers called “planned obsolescence.” Products were either made to last only a short time so that they would have to be replaced frequently (adding to sales) or they were continually upgraded, more commonly in style than in quality. It was an idea that began long before World War II with Gillette’s disposable razors and soon took on a larger life.

Henry Ford, who helped start the ’20s consumer boom by paying his workers a then-fantastic five dollars a day, was a bit of a conservative about style, once promising that consumers could have one of his famous Model Ts in any color as long as it was black. But just before the Great Depression, General Motors introduced the idea of the annual model change. It was an idea that took off after World War II. Families were encouraged to buy a new car every year. “They were saying the car you had last year won’t do anymore, and it won’t do anymore because it doesn’t look right,” Strasser explains. “There’s now a new car and that’s what we want to be driving.”

INSTANT MONEY

Of course, none but the richest of Americans could afford to plunk down a couple thousand dollars on a new car every year, or on any of the other new consumer durables that families wanted. Never mind, there were ways to finance your spending spree. “The American consumer! Each year you consume fantastic amounts of food, clothing, housing, amusements, appliances, and services of all kinds. This mass consumption makes you the most powerful giant in the land,” pipes the narrator in a cute mid-’50s animated film from the National Consumer Finance Association.

“I’m a giant,” boasts Mr. American Consumer, as he piles up a massive mountain of stuff. And how does he afford it? Loans, says the film: “Consumer loans in the hands of millions of Americans add up to tremendous purchasing power. Purchasing power that creates consumer demand for all kinds of goods and services that mean a rising standard of living throughout the nation.” You can probably already hear the drumroll in your mind.

A TV ad for Bank of America made about the same time shows a shaking animated man and asks, “Do you have money jitters? Ask the obliging Bank of America for a jar of soothing instant money. M-O-N-E-Y. In the form of a convenient personal loan.” The animated man drinks from a coffee cup full of dollars, stops shaking, and jumps for joy.2

It was a buy now, pay later world, only to become more so with the coming of credit cards in the sixties.

AMERICA THE MALLED

During the 1950s and 1960s, the rush to suburbia continued (and hasn’t stopped yet). In 1946 the GI Bill spurred it along. Ten years later, another government program did the same. President Dwight D. Eisenhower announced the beginning of a vast federal subsidy to create a nationwide freeway system. In part the system was sold as national defense—roads big enough to run our tanks on if the Russians invaded. The new freeways encouraged a mass movement to even wider rings of suburbs. All were built around the automobile and massive shopping centers, whose windows, according to one early ’60s promotional film, reflected “a happy-go-spending world.”

“Shopping malls,” the film continues, “see young adults as in need of expansion [interesting choice of words, perhaps anticipating “supersize” meals]. People who buy in large quantities and truck it away in their cars. It’s a big market!” Enthusiastically, the narrator continues, “These young adults, shopping with the same determination that brought them to suburbs in the first place, are the goingest part of a nation of wheels, living by the automobile.” Going to the mall was, for these determined consumers, an adventure worthy of Mount Everest, at least according to this film, which later describes the consumers’ hardest challenge as finding their cars again in the giant mall parking lots. Sound familiar?

By 1970, Americans were spending four times as much time shopping as were Europeans. The malls encouraged Sunday shopping, then as rare in the United States as it still is in Europe. To its everlasting credit, Sears, Roebuck & Company opposed opening its store on Sunday, on the grounds that it wanted “to give our employees their Sabbath.” But by 1969 it caved to the competition, opening on Sundays “with great regret and some sense of guilt.”3

THE BOX THAT ENLIGHTENED

The big economic boom wasn’t the result of any one thing. A series of synchronous events made it possible: pent-up demand, government loans, expanded credit, suburbanization, longer shopping hours, and mallification. But perhaps no single cause was more responsible for the emerging postwar epidemic of affluenza than the ubiquitous box that found its way into most American homes by the 1950s.

Television showed everyone how the other half (the upper half) lived. Its programs were free, made possible only because of the sale of time to advertisers who hawked their wares during and between the features. Crude at first, the ads became increasingly sophisticated—both visually, because of improving technology, and psychologically, as batteries of experts probed the human mind to find out how to sell most effectively.

The early TV ads relied a great deal on humor—”Any girl can find a good husband, but finding the right man to do your hair, now that’s a problem.” Like many print and radio ads before them, they played on anxieties about personal embarrassment, warning of horrors like “BO” (body odor). But mostly, they just showed us all the neat stuff that was out there just waiting to be bought.

On TV, convenience was the new ideal, disposability the means. “Use it once and throw it away.” TV dinners in disposable aluminum trays. “No deposit, no return” bottles. People in commercials danced with products. The airwaves buzzed with jingles. John still can’t stop singing one that must have been on the tube every night when he was a kid: “You’ll wonder where the yellow went, when you brush your teeth with Pepsodent.”

AFFLUENZA’S DISCONTENTS

Of course, not everyone wanted Americans to catch affluenza. “Buy only what you really need and cannot do without,” President Harry Truman once said on TV. By the early ’50s, educational films were warning school kids about over-spending. But those films were, in a word, boring. No match for TV’s wit and whiz. In one, a nerdy-looking character called Mr. Money teaches students to save. One can imagine the collective classroom yawns it produced. In another, the voice of God says, “You’re guilty of pouring your money down a rathole. You forget that it takes a hundred pennies to make a dollar.” The visuals are equally uncompelling: a hand puts a dollar in a hole in the dirt labeled—you guessed it—”Rathole.”

Meanwhile, far-sighted social critics from both Left and Right warned that America’s new affluence was coming at a high price. The conservative economist Wilhelm Röpke feared that “we neglect to include in the calculation of these potential gains in the supply of material goods the possible losses of a non-material kind.”4 The centrist Vance Packard lambasted advertising (The Hidden Persuaders, 1957), keeping up with the Joneses (The Status Seekers, 1959), and planned obsolescence (The Waste Makers, 1960). And the liberal John Kenneth Galbraith suggested that a growing economy fulfilled needs it created itself, leading to no improvement in happiness. Our emphasis on “private opulence,” he said, led to “public squalor”—declining transit systems, schools, parks, libraries, and air and water quality. Moreover, it left “vast millions of hungry and discontented people in the world. Without the promise of relief from that hunger and privation, disorder is inevitable.”5

The affluent society had met its members’ real material needs, Galbraith argued at the end of his famous book. Now it had other, more important things to do. “To furnish a barren room is one thing,” he wrote. “To continue to crowd in furniture until the foundation buckles is quite another. To have failed to solve the problem of producing goods would have been to continue man in his oldest and most grievous misfortune. But to fail to see that we have solved it, and to fail to proceed thence to the next tasks, would be fully as tragic.”6

YOUNG AMERICA STRIKES BACK

During the following decade, many young Americans sensed that the critics of consumerism were right. A counterculture arose, rebuking materialism. Thousands of young Americans, inspired by books like Charles Reich’s The Greening of America, left the cities for agricultural communes practicing simple living, the most successful of which still survive today.

Many of the young questioned American reliance on growth of the gross domestic product as a measure of the nation’s health. In that they were supported by President Lyndon Johnson, whose “Great Society” speech warned that America’s values and beauty were being “buried by unbridled growth.”7 His nemesis, the popular senator Robert F. Kennedy, agreed. During Kennedy’s 1968 campaign for president (which ended when he was assassinated), Bobby Kennedy stressed that

we will find neither national purpose nor personal satisfaction in a mere continuation of economic progress, in an endless amassing of worldly goods.… The gross national product includes the destruction of the redwoods and the death of Lake Superior.8

By the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970, young Americans were questioning the impact of the consumer lifestyle on the planet itself. Leading environmentalists, like David Brower, founder of Friends of the Earth, were warning that the American dream of endless growth was not sustainable.

Then, in 1974, a nationwide oil shortage caused many people to wonder if we might run out of resources. Energy companies responded as they still do today, by calling for more drilling. “Rather than foster conservation,” writes the historian Gary Cross, “President Gerald Ford supported business demands for more nuclear power plants, offshore oil drilling, gas leases and drilling on federal lands,” as well as “the relaxation of clean air standards.”9

CARTER’S LAST STAND

But Ford’s successor, Jimmy Carter, disagreed, promoting conservation and alternative energy sources. Carter went so far as to question the American dream in his famous “national malaise” speech of 1979. “Too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption,” Carter declared. It was the last courageous stand any American president ever made against the spread of affluenza.10

And it helped bring about Carter’s defeat a year later. “Part of Jimmy Carter’s failure,” says the historian David Shi, “was his lack of recognition of how deeply seated the high, wide, and handsome notion of economic growth and capital development had become in the modern American psyche.”

The Age of Affluenza had begun.