CHAPTER 10

A cancerous culture

The only chance of satisfaction we can imagine is getting more of what we have now. But what we have now makes everybody dissatisfied. So what will more of it do—make us more satisfied, or more dissatisfied?

—A CLIENT OF PSYCHOLOGIST JEREMY SEABROOK

Maybe the proof is in the pillow: the fact that more than thirty million Americans have chronic insomnia is one convincing indicator that all is not perfect in Camelot. We spend about $25 billion a year on sleep products, from pills to white-noise apps to comfort-zoned beds, but sleep researchers tell us that on average, humans in overdeveloped countries like ours sleep a full hour and a half less than we did a hundred years ago. In addition to peddling the pills that summon creepy luminescent green moths to our bedrooms in the TV ads, pharmaceutical companies in 2012 hustled Americans for $325 billion in prescription drugs. Among many other prescriptions (with, on average, seventy potential side effects apiece) we swallow half the world’s antidepressants.1

The US Food and Drug Administration estimates that more than a hundred thousand Americans die from “properly” prescribed drugs each year2 (compared with about ten thousand deaths from illegal drugs), making prescription drugs the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States. What’s the problem? Well, in a word, delirium. Over the last generation, the United States became ground zero for an all-consuming epidemic that has become a global frenzy. Price tags and bar codes began to coat the surfaces of our lives, as every single activity became a transaction. Eating, entertainment, socializing, health, even religion—all became market commodities. To jump-start sex, take a pill. To eat, grab a couple of pizzas or, if the stock is doing well, order a three-course dinner (complete with a floral arrangement) from a store-to-door caterer. To exercise, join a health club. For fun, buy a crate-load of products on the Internet. To quit smoking, buy a nicotine patch, or ask your doctor for clinical doses of laughing gas! (No joke.)

In recent years our household budgets have expanded to include day care, dog care, elder care, health care, lawn care, house care—in direct proportion to our quest to be “care-free.” But this way of life is not sustainable, nor is it genuinely satisfying. Our consumption habits demand more debt and longer work hours, reducing our social connections, a central foundation of happiness. To compensate for the feelings of loneliness, we then buy more stuff, seeking friendship through products. This way of life tries to meet nonmaterial needs with material goods, a losing strategy.

The 2013 OECD Factbook—which compares data from the twenty-seven member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (many of the Factbook’s tables also include others such as China, India, Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, and South Africa)—doesn’t paint a pretty picture of real wealth in the United States. In traditional measurements of wealth, such as GDP per capita, the Stars and Stripes scores in the top five; and in disposable household income, the top fifteen. But look at some of the other categories: for example, only sixteenth best in household debt. Other rankings are twenty-first in suicide rate; twenty-fourth in renewable energy as a percentage of total energy; twenty-fifth in both hours worked and part-time employment; twenty-sixth in doctors per thousand adults; twenty-eighth in life expectancy; thirty-third in municipal waste per capita; thirty-eighth in water consumption per capita; thirty-ninth in obesity; thirty-eighth in total carbon dioxide emissions; forty-first in health care expenditures as a percentage of GDP.3

The results of a 2013 National Institutes of Health–commissioned study are no less shameful for Americans.4 Compared with sixteen other developed countries (Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) the United States scored at or near the bottom in infant mortality, traffic deaths, adolescent pregnancy, AIDS, obesity, heart disease, lung disease, and activity-limiting diseases like arthritis. It doesn’t stop there, either: The United States spends more on its military than the next twelve nations on the list combined; it’s the best in the world at imprisoning people; it has the highest divorce rate and the highest rate of both illicit and prescription drug use.

The progressive economist David Korten points to other indicators of decline in human capital—“skills, knowledge, psychological health, capacity for critical thought and moral responsibility”—as well as social capital, “the enduring relationships of mutual trust that are the foundation of healthy families, communities and societies.”5 Simply put, Korten believes our economic crisis is about a broken paradigm that consistently places financial values ahead of life values. Something needs to be done, quickly, partly to model a healthier lifestyle to those in other countries who would (catastrophically) follow us on our wild goose chase. If money can’t buy better results, what can? We believe the answer is fundamentally simple: our culture needs different priorities guided by a different definition of success.

The psychologist Richard Ryan points to scores of studies—his own among them—showing why material wealth does not create happiness. “We keep looking outside ourselves for satisfactions that can only come from within,” he explains. In the human species, happiness comes from achieving intrinsic goals like giving and receiving love. Extrinsic goals like monetary wealth, fame, and appearance are surrogate goals, often pursued as people try to fill themselves up with “outside-in” rewards. “People with extrinsic goals sharpen their egos to conquer outer space, but they don’t have a clue how to navigate inner space,” Ryan says.

“We’ve documented that unhappiness and insecurity often initiate the quest for wealth,” he continues. In three studies with 140 adolescents, Ryan and colleague Tim Kasser showed that those with aspirations for wealth and fame were more depressed and had lower self-esteem than other adolescents whose aspirations centered on self-acceptance, family and friends, and community feeling.6

“The wealth seekers also had a higher incidence of headaches, stomachaches, and runny noses,” Ryan says. He believes that while people are born with intrinsic curiosity, self-motivation, and playfulness, too often these qualities are squelched by “deadlines, regulations, threats, directives, pressured evaluations, and imposed goals” that come from external sources of control rather than self-motivated choices and goals. Their findings do not prove that rich people are always unhappy (some are, some aren’t, depending on how they use their money). But they do point out that seeking extrinsic goals can dislodge us from vital connections with people, nature, and community—and that can make us unhappy.

Dysfunctions and disconnects seem to disrupt everyone’s life these days, rich and poor alike. Donella Meadows cuts to the heart of it in Beyond the Limits:

People don’t need enormous cars; they need respect. They don’t need closets full of clothes; they need to feel attractive and they need excitement and variety and beauty. People don’t need electronic equipment; they need something worthwhile to do with their lives. People need identity, community, challenge, acknowledgment, love, and joy. To try to fill these needs with material things is to set up an unquenchable appetite for false solutions to real and never-satisfied problems. The resulting psychological emptiness is one of the major forces behind the desire for material growth.7

Opinion polls reveal that Americans crave reconnection with the real sources of satisfaction, but we can’t find our way back through all the jingles, static, and credit card bills.

FINDING REAL WEALTH

The more real wealth we have—such as friends, skills, libraries, wilderness, and afternoon naps—the less money we need in order to be happy. Throughout history, many civilizations have already discovered this truth, for example as the cedars of Lebanon and the topsoil of northern Africa were used up, cultures finally wised up, learning to substitute knowledge, playfulness, ritual, and community for material goods. During resource-scarce periods such as the eighteenth century, the Japanese culture developed a national ethic that centered on moderation and efficiency. An attachment to the material things in life was seen as demeaning, while the advancement of crafts and human knowledge were seen as lofty goals, as were cultural refinements such as kenjutsu (fencing), jiujitsu (martial arts), saka (tea ceremony and flower arrangement), and go (Japanese “chess”). The culture became so highly refined that the firearm was banned as too crude and destructive a method of settling differences. In this “culture of contraction,” an emphasis on quality became ingrained in a culture that eventually produced world-class solar cells and Toyota Priuses. The Japanese ethical goal, mottainai, which loosely translates as “Don’t waste resources; be grateful and respectful,” is evidence of a culture that aspires to quality.

CULTURE SHIFT

If asked what we each want out of life, most would probably say we want less stress than we have now, and more laughter. We want a greater sense of control over how we spend our time, including fewer everyday details like security codes, telephone calls to be made, and endless consumer choices (which health insurance? which sunscreen? which mutual fund?). We want more energy and vitality and fewer “worn-out” days. We want the people in our lives to really understand and care about us—people whom we love and respect in return; activities and passions that foster creativity and self-expression; a sense that our lives have meaning and purpose; a feeling of being safe in our neighborhoods and having the respect of our peers. These are the kinds of things that make us happy.

When we’re lucky enough to have these important things in our lives, we are less likely to beg doctors for antidepressants and more likely to sleep soundly on a cushion of well-being. We’re less likely to be dependent on the approval of others and more likely to know in our own hearts that we’re on the right track. We spend less time at the mall hunting and gathering what we hope are the latest fashions and hippest products, and more time completely absorbed in activities that make the time fly past. When we understand who we are and what we want, we have a greater sense of clarity and direction. Rather than feel that something is wrong or insufficient, we feel content. We know instinctively that we have “enough,” and those nagging, insecure voices go silent at last.8

LOWER ON THE HIERARCHY?

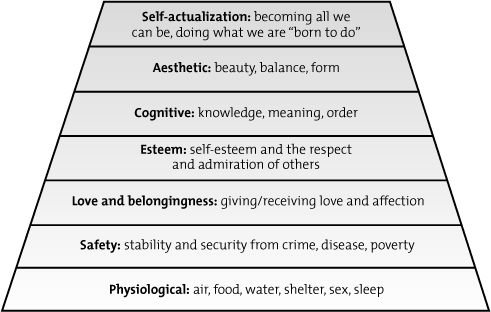

Many of us know a few unique individuals—often elderly—who are healthy, wise, playful, relaxed, spontaneous, generous, open-minded, and loving: people who focus on problems outside themselves and have a clear sense of what’s authentic and what’s not. They are people for whom life gets in the way of work, on purpose. In fact, work is play, because they choose work they love. The sociologist Abraham Maslow called these people “self-actualized.” Maslow concluded that most Americans had met the basic physical needs (the only ones that are primarily material) and security needs and had progressed to at least the “love and belongingness” rung of the hierarchy. Many individuals were higher than that.

MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

The question is, has America—weakened by the fever of affluenza—slipped down the hierarchy in the last thirty years? It seems the rungs of Maslow’s ladder have become coated with slippery oil, as in a cartoon. According to polls, we’re more fearful now. We’re more insecure about crime, the possible loss of our jobs, and catastrophic illness. How can we meet innate needs for community when sprawl creates distance between people? How can we feel a sense of beauty, security, and balance if beautiful open spaces in our communities are being smothered by new shopping malls and rows of identical houses? How can we have self-respect in our work if it contributes to environmental destruction, social inequity, and isolation from living things? (The highest incidence of heart attacks is on Monday morning; apparently some would rather die than go back to work.)

IN THE FLOW

The work of the psychologist and author Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi provides valuable insights about where we need to go from here. In his classic book, Flow, he observes, “In normal life we keep interrupting what we do with doubts and questions. ‘Why am I doing this? Should I perhaps be doing something else?’ Repeatedly we question the necessity of our actions, and evaluate critically the reasons for carrying them out.”9

After decades of interactive interviews with people from all walks of life—elderly Korean women and Japanese teenage motorcycle gang members; assembly line workers in Chicago; artists, athletes, surgeons—Csikszentmihalyi identified a universal human goal: “optimal experience,” or flow, in which “the ego falls away and time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved, and you’re using your skills to the utmost.” The psychologist’s interviewees consistently reported that flow occurs when they are challenged and yet feel that they are, or could become, equal to the challenge, when they have a sense that they are improving their skills, and when there are clear goals. To be genuinely happy, he concluded, we need to actively create our experiences and our lives, rather than passively let the media and marketers create it for us.

Writes Csikszentmihalyi, “What we found was that when people were pursuing leisure activities that were expensive in terms of the outside resources required—activities that demanded expensive equipment, or electricity, or other forms of energy measured in BTUs, such as power boating, driving, or watching television—they were significantly less happy than when involved in inexpensive leisure. People were happiest when they were just talking to one another, when they gardened, knitted, or were involved in a hobby; all of these activities require few material resources, but they demand a relatively high investment of psychic energy.”10

For the ancients, happiness was a function of rational development; a reward for leading a virtuous, balanced life. Aristotle, for example, believed that happiness must be evaluated over a lifetime (not just in the lick of an ice cream cone, as in our world of instant gratification). Happiness, he believed, consists of a blend of moderation, gentleness, modesty, friendliness, and self-expression: harmony and balance in which desire is tempered through rational restraint. Try finding these qualities on sale in a typical American megamall.

The author and activist Alan Durning lyrically reminds us where we belong and where we can feel truly grounded: “In the final analysis, accepting and living by sufficiency rather than excess offers a return to what is, culturally speaking, the human home: to the ancient order of family, community, good work and good life; to a reverence for skill, creativity, and creation; to a daily cadence slow enough to let us watch the sunset and stroll by the water’s edge; to communities worth spending a lifetime in; and to local places pregnant with the memories of generations.”11

ARE WE CHEATING ON OUR GENES?

What kind of a deal have we arranged as a national culture? In exchange for some hundred thousand hours per lifetime of commuting and jobs that often fail to inspire us, we often settle for houses too big to maintain, superficial connections with people, easily broken gadgets, and nutrition-free processed food: counterfeit rewards that can’t possibly meet our needs. So why do we cling to them? Apparently because that’s the way our culture is programmed and because we are physically, psychologically, and socially addicted.

In an ancient bundle of the human brain, the nucleus accumbens—aka the “reward center”—continuously dispenses chemical substances like dopamine when our actions register “hits” of pleasure. A kind of chemical pinball machine, the reward center’s underlying purpose is to seek out and score survival needs like food, water, leisure, energy, sex, and social connection.

The problem is, the reward center isn’t evolving as fast as technology. For example, sugar is chemically rewarded by the reward center because of its apparent energy potential, but the human body has never experienced anything as concentrated as a box of Dunkin’ Donuts or Pop-Tarts. We behave as if we’ve discovered a blueberry bog when really it’s just another mood swing and a pound of weight we’ll have to carry around. Sex seems to spell survival to the reward center, despite the anthropologically unfamiliar specter of overpopulation. Fast-moving images on television seem to be related to survival, so we surf these images to score chemical rewards. (Laboratory rats are so addicted to self-induced stimulation of the reward center that they lose 40 percent of their body weight, and die.)12 Why bother to “save the planet,” learn to handcraft a table, or make a new friend when our reward centers feast on calculated hits and bits of images, tastes, memories, emotional cocktails that promise pleasure, security, vitality, and social conquest?

ADDICTED TO GENEROSITY

The good news is that our collective intuition remains fundamentally intact. We still have a decent shot at creating a healthy new identity—a different way of living. We just need to collectively embrace the “click” of culture shift. In other words, demand a more sensible direction. It’s time for a cultural revolution, a social tsunami, using proven interventions like nonviolent civil disobedience, focused social media and mentoring, and strategies Dave calls anthropolicy (policies aligned with what we truly need) and biologic (designing with nature rather than against it).

Here’s why we’re beginning to pull our civilization back to its set point: our primordial bonds with generosity and altruism are even stronger than our cultural affair with stimulation, speed, and gratification. By examining human responses to various images with MRI technology, neurologists observe that altruism and cooperation outcompete even virulent addictions like gambling, drugs, war, shopping, and superficial sex. One of the very strongest, most satisfying stimulants is the universal bond of love between mother and child. Healthy hormones flow like a mountain stream in response to images of nursing and developmental playing.

Can we tap into the power of generosity and trust to override the momentum of a quick-hit culture? Of course we can; we’ve already returned to our anthropological set point many times before. By trashing counterfeit rewards and culturally destructive behavior, we can make new agreements about what it means to be unselfish and truly successful. Instead of deadlines and dying species, we’ll choose lifelines and living wealth.

WANTING WHAT WE HAVE

An old story about a native Pacific Islander rings true in the Age of Affluenza. A healthy, self-motivated native relaxes in a hammock that swings gently in front of his seaside hut as he plays a wooden flute for his family and himself. For dinner, he picks exotic fruits and spears fresh sunfish. He feels glad, and lucky to be alive. (Think of it—he’s on “vacation” most of the time!) Suddenly, without warning, affluenza invades the island. Writes Jerry Mander, “A businessman arrives, buys all the land, cuts down the trees and builds a factory. He hires the native to work in it for money so that someday the native can afford canned fruit and fish from the mainland, a nice cinderblock house near the beach with a view of the water, and weekends off to enjoy it.”13 Like Pacific Islanders, we’ve been cajoled into meeting most of our needs with products brought to us courtesy of multinational corporations—what you might call takeout satisfaction. (From the maternity ward at a franchise Columbia/HCA hospital to an embalming room owned by the Houston-based Service Corporation International—which today handles the final remains of one of every eight Americans—we are wards of the Corporation.) As we consent to identify ourselves with the social species “consumer,” our sense of confidence becomes dependent on things largely out of our control. For example, we suffer mood swings with the rising and falling of economic tides. If overtime work hasn’t gotten us that BMW yet, maybe more overtime will, along with another refinance of our house.… Are we still, somehow, convinced we’ll find peer approval, self-esteem, and meaning in material things if we just keep looking?