CHAPTER 24

Vital signs

The gross national product includes air pollution and advertising for cigarettes, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors, and jails for the people who break them.… It does not allow for the health of our families, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play.

—ROBERT KENNEDY, 1968

A patient in remission from cancer requires routine checkups to evaluate how things are going. It’s the same with affluenza. Once we’re on the road to recovery, annual checkups help prevent costly, energy-sapping relapses. Lingering germs like debt, susceptibility to advertising, and possession obsession can cause recurrences not only in individuals but in communities and national economies as well. Checkups help track these germs down where they hide, and wipe ’em out!

ENOUGH?

Too often, life’s complexities get boiled down to a single nagging question: “Do we have enough money?” Vicki Robin, the coauthor of Your Money or Your Life, believes this question is far too narrow. Pointing out that money is really what we trade our life energy for, she asks,

Do we receive fulfillment, satisfaction, and value in proportion to life energy spent?

Is this expenditure of life energy in alignment with our values and life purpose?

You wouldn’t expect weight alone to measure whether a person is sick or well. Nor would blood pressure, by itself, tell you if a person is healthy. Similarly, a grand total of expenditures (like GDP) blindly measures quantity but not quality. It can’t distinguish thriving from surviving.

MAKING PERSONAL HISTORY

A very simple measurement of well-being, or gladness to be alive, is whether you’re eager to get out of bed in the morning. But the cold, hard truth is, you may jump energetically out of bed one morning only to be laid off by midafternoon. Or worse, you could suddenly find out you have an illness even more critical than affluenza and only have a year to live. Are you really doing what’s most important, such as making connections with people, ideas, and nature? What have you always wanted to do that you haven’t done yet, because you’ve been too busy making and spending money? How can you do more of what you’re most proud of accomplishing?

These are the kinds of questions that enable us to take stock, and take control, of our lives. Honest answers strip away illusions and worn-out patterns. They help get to the heart of what really matters. As Irvin Yalom observed, “Not to take possession of your life plan is to let your existence be an accident.”1

A good first step in repossessing your life is to identify what you value most. Record the most significant events of your life in a notebook, including personal relationships, births and deaths, achievements, adventures, enlightenments, and disappointments. Recall the first house of your adult life, the first time you fell in love. Note the relative importance of material possessions. Have they satisfied as fully as the connections, emotions, and actions of your life?

Now, jot down a list of principles that are most important to you—things like fairness, trust, unconditional love, compassion, taking care of nature, financial security, fearlessness, maintenance of health. These are the principles to base your life decisions on, because they are your highest values. Apply these principles in your relationships, your career, and your plans for the future, and ask yourself whether the constant pursuit of wealth and stuff isn’t more effort than it’s worth.

When you perform your annual checkup, get out your notebook and review the memoir in progress. Do any events of the past year deserve inclusion in life’s “greatest hits”? With another year behind you, are there events that now seem less important? Which people from the past year of your life do you most admire? Have you followed your personal code of ethics, with maybe a few forgivable exceptions?

WHAT REALLY MATTERS

Now comes the knockout punch—good night, affluenza! By cross-referencing your personal history and values with your annual expenditures, you can determine if you’re living life on your terms. Every year when you file your taxes, also file your self-audit—but don’t give yourself a deadline. (After all, the idea here is to give yourself a lifeline.) Are your consumption expenditures consistent with what really matters? Have you spent too much on housing, entertainment, or electronic gadgets? Did your expenditures cause you to work overtime, in turn reducing family time? Are you happy with the charitable contributions you made? Are you getting real value back from the money you spent?

COMMUNITY AND NATIONAL CHECKUPS

Newscasters, investment brokers, and lenders are among those who rely on the gross domestic product as an indicator of national prosperity. But does GDP really tell us if our economy’s vital signs are healthy? Back in 1999, one group of economists explained why they didn’t think so.

Imagine receiving an annual holiday letter from distant friends, reporting their best year, because more money was spent than ever before. It began during the rainy season when the roof sprang leaks and their yard in the East Bay hills started to slide. The many layers of roofing had to be stripped to the rafters before the roof could be reconstructed, and engineers were required to keep the yard from eroding away. Shortly after, Jane broke her leg in a car accident. A hospital stay, surgery, physical therapy, replacing the car, and hiring help at home took a bite out of their savings. Then they were robbed, and replaced a computer, two TVs, a VCR, and a video camera. They also bought a home security system, to keep these new purchases safe.2

These people spent more money than ever and contributed slightly to a rise in GDP, but were they happier? Not likely, in that year from hell. And what about a nation in which GDP continues to grow? Are its citizens happier? Clearly, that depends on how the money is being spent.

Politicians point to a swelling GDP as proof that their economic policies are working, and investors reassure themselves that with the overall expansion of the economy, their stocks will also expand. Yet even the chief architect of the GDP (then GNP), Simon Kuznets, believed that “the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement like GNP.”3

Here’s why: Although the overall numbers continue to rise, many key variables have grown worse. As we have already mentioned, the gap between the rich and everyone else is expanding. In addition, the nation is borrowing more and more from abroad, a symptom of anemic savings and mountains of household debt. The economic and environmental costs of our addiction to fossil fuels continue to mount.

When a city cuts down shade trees to widen a street and homeowners have to buy air conditioning, the GDP goes up. It also goes up when families pay for day-care and divorce, when new prisons are built, and when doctors prescribe antidepressants. In fact, careful analysis reveals much of the economy as tracked by GDP is based on crime, waste, and environmental destruction!

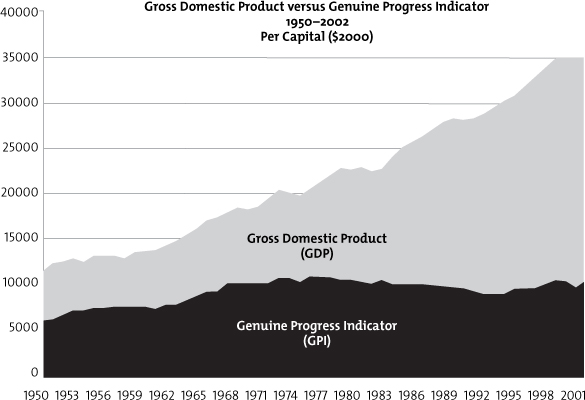

In contrast to GDP—which lumps all monetary transactions together—a measurement of success called the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), first proposed in 1995, evaluates the expenses, adding in “invisible” assets such as housework, parenting, and volunteer work, but subtracting “bads,” including the following from the national economy:4

• cost of crime

• cost of family breakdowns

• loss of leisure time

• cost of underemployment

• cost of commuting

• cost of household pollution abatement

• cost of automobile accidents

• cost of water pollution

• cost of air pollution

• cost of noise pollution

• depletion of nonrenewable resources

• cost of long-term environmental damage

• cost of ozone depletion

• loss of old-growth forests

Source: Redefining Progress, Why Bigger Isn’t Better: The Genuine Progress Indicator—2002 Update (San Francisco: Redefining Progress)

Using this metric as our measure of national progress, we find that although GDP has increased dramatically since the mid-1970s, GPI has remained flat or even fallen. GPI started out as an idea in a think tank, but it is gaining steam among policy makers. The states of Maryland and Vermont now officially measure their GPI, while Oregon and Utah have plans in the works, and leaders from some twenty states met recently at a conference called “Beyond GDP” to talk about how each could apply the idea.5 Oregon’s dynamic first lady, Cylvia Hayes, founder of a clean economy consulting group called 3EStrategies, set the tone:

We tend to manage what we measure. The primary problem with using the GDP metric is that we are managing for constant economic growth, without measuring the true costs of that growth.

In 1962 Simon Kuznets, the man who created the GDP, warned, “Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between costs and returns, and between the short and long run. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what.”

… One example of Beyond GDP metrics is the Genuine Progress Indicator. The goal of the Genuine Progress Indicator is to measure the actual societal well-being and health generated by economic activity. The Genuine Progress Indicator uses 26 metrics and consolidates critical economic, environmental and social factors into a single framework in order to give a more accurate picture of the progress—and the setbacks—resulting from our economic activities.6

Maryland governor Martin O’Malley argued that it is not growth, but the kind of growth, that matters:

In many ways, we Marylanders, think of ourselves as pro-growth Americans—but before you get “wiggy” about that term, let me explain: Like you, we believe in growing jobs and growing opportunity. Like you, we believe in children growing healthy, growing educated, and growing strong. We believe in grandparents growing old with dignity and with love. We believe in growing trees, growing sustainable Bay fisheries, growing food locally to feed our citizens. But not all growth is good.7

GPI is a step in the right direction, though as Ronald Colman, who first developed a GPI metrics for Atlantic Canada, has observed, most GPI models currently in use still start with consumption of goods and services as an unquestioned positive, then add and subtract assets and costs from that. In his view, a better GPI model would begin with security, fairness, and access to work. We agree.

Additional measures are needed to track our use of natural resources—what we have versus what we use. Measures like the ecological footprint (www.myfootprint.org) help us to see how our consumptive lifestyles are annually eating up resources faster than nature can regenerate them. A close look at our “footprint,” the amount of productive land and water needed to produce our lifestyles, shows that we would need five planets if everyone on earth were to suddenly consume as Americans do. Like the spendthrift who goes on a shopping spree with a savings account, we won’t have the steady supply of interest coming to us from nature in future years if we keep this up.

A number of years ago, the Swiss economist Mathis Wackernagel, cocreator of the footprint idea, told David, “The ecological footprint is gaining a foothold in the market analysis. Some banks have hired us to analyze the security of government bonds. They want to know, Do countries have ecological deficits? Are they over-spending their natural wealth?”

The Genuine Progress Indicator and the ecological footprint are really common sense with an analytical, pragmatic edge. National vitality, like personal health and community health, is about real things like the health of people, places, natural capital, and future generations. At all levels of our society, it’s time to schedule a holistic annual checkup. And the good news is that, led by a tiny and poor country in the Himalayas, the world is starting to take notice.

GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS

Coming Home is a sweet little children’s book about a girl named Tashi Choden, who lives in the far-off city of Thimphu, the capital of Bhutan, a nation of seven hundred thousand tucked between two giant world powers, China and India. It’s a country that could hardly be more unlike the United States, except … Except that this story of the high school life of a fictional 15-year-old would not feel out of place to American teenagers. If the characters’ names were not Tashi, Pema, Ugyen, Leki, Lhazom, and Tobden, you might think the story was set in suburban California. The lives of these young people revolve around popularity cliques, parties, sports, and the name-brand apparel they wear. They banter in American slang and proudly display their possessions:

I was wearing my white Reeboks.… Tenzin was wearing an oversized Nike T-shirt.… Pema looked cute with red Superstars.… and Ugyen was in faded jeans with Converse high-tops.8

In Bhutan yet!

Here, even in one of the world’s poorest countries, with a per capita income of $3,000, affluenza has clearly taken deep root. In the story, the teens discover the superficiality of their choices and the value of their friendships and their own traditions. But in reality, the fight against affluenza is not an easy one even in a place like this, whose Buddhist cultural traditions value moderation and simplicity.

But Bhutan is not accepting affluenza lying down.

Several decades ago, its King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, challenged Western consumer culture by famously declaring that “Gross National Happiness is more important than Gross National Product.” Since then, under the leadership of Dasho Karma Ura, a brilliant Bhutanese educator and artist, the former kingdom (now with a parliamentary government) has looked to international scholars in many fields to help create the Gross National Happiness Index (www.grossnationalhappiness.com), its national measure of progress. The index uses survey data to see how well Bhutanese are doing in a range of “domains” deemed essential to human well-being and happiness by experts in the field. While these domains include income, or “living standards,” they also include eight other aspects of quality of life: health, psychological well-being, environment, cultural vitality, community vitality, government, time balance, and education.

In the past few years, Bhutan has been taking its ideas to the rest of the world, promoting the concept of “Equitable and Sustainable Well-Being and Happiness” in the United Nations. In April 2012 its prime minister, Jigmi Thinley, spoke to a gathering of 800 people at the UN:

The time has come for global action to build a new world economic system that is no longer based on the illusion that limitless growth is possible on our precious and finite planet or that endless material gain promotes well-being. Instead, it will be a system that promotes harmony and respect for nature and for each other; that respects our ancient wisdom traditions and protects our most vulnerable people as our own family, and that gives us time to live and enjoy our lives and to appreciate rather than destroy our world. It will be an economic system, in short, that is fully sustainable and that is rooted in true, abiding well-being and happiness.9

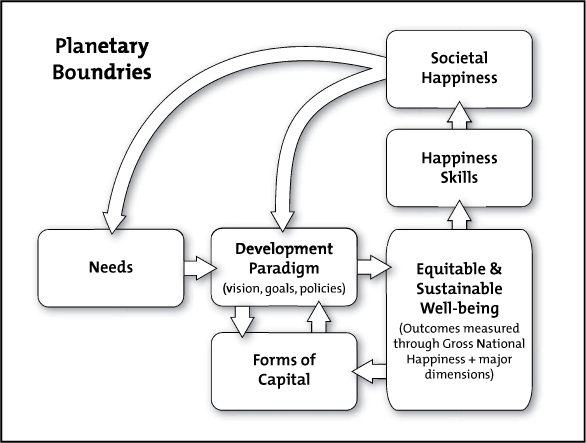

John has been part of a team of international advisers helping Bhutan’s government as it promotes its “new world economic system,” or New Development Paradigm, as it is now called. While in Bhutan, he watched as Enrico Giovannini, now Italy’s minister of labor and social issues, first drew the diagram below with a stick in the sand, as a model of the paradigm.

The model starts with human needs, such as those described by Abraham Maslow (see chapter 10), and by a member of Bhutan’s UN advisory group, the famed Chilean economist Manfred Max-Neef. The development paradigm is the economic system, modified in each society by market rules, policies, and cultural expectations that employ resources, known as forms of capital, to meet needs. Capital, until recently, referred to the factories, physical infrastructure, and finances that businesses used to provide employment and consumer goods, but its meaning has been expanded as part of the new discipline of ecological economics. Forms of capital now also include natural capital (the resources of nature, to which ecological economists now assign monetary value), human capital (the health, competence, and productivity of workers), and social capital (the value of social connection and nonmarket institutions such as government and the nonprofit sector).

The new development paradigm promoted by Bhutan pays attention to all needs (and even extends that consideration to other species), and to the nine key domains of well-being, not just those so far counted by GDP. It is understood that such a system must be equitable, without large gaps between rich and poor, and that it must be sustainable; that is, it cannot grow beyond the planetary boundaries shown in the diagram. The new economy must fit within the earth’s limits; indeed, the economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the earth.

Despite denial from the political Right, modern analysis of well-being confirms the basic accuracy of the so-called Easterlin Paradox—income growth and GDP matter greatly for the happiness of very poor people, but their effects flatten out once a degree of modest comfort is attained.10 Even while gains continue, they are far too modest to justify their costs in equity and sustainability.

Moreover, the economist Herman Daly argues that growth refers to purely quantitative expansion, while development denotes qualitative improvement. As Manfred Max-Neef puts it, “Growth is not the same thing as development, and development does not necessarily require growth.” Indeed, as we have seen, if such growth comes at the expense of equality, sustainability, or the ability to meet essential nonmaterial needs, it may actually impede development and well-being.

In this model, the terms happiness and well-being, while often spoken of as just two ways to say the same thing, are not quite synonymous. Often, modern advocates of life satisfaction quarrel about this, with academics sometimes cringing over what they believe is the amorphousness of the word happiness, while ordinary people often find the term well-being overly wonky. But in this model, equitable and sustainable well-being is what can be measured through objective data—such things as income levels, life expectancy, literacy, pollution, voter participation, leisure hours, rates of depression, unemployment, poverty, and so on. In each domain, there are levels of sufficiency that are needed to be able to say that well-being has been achieved in a society and for a domain. The objective conditions of life are the goals of public policy.

But people may have sufficient conditions for a good life without being happy. Happiness in this model is the subjective sense of people’s well-being, determined by survey questions such as: How do you feel about your health? your mental state? your access to nature? your finances? your time balance? your purpose in life? People are also asked to evaluate their overall life satisfaction, using several 1-to-10 scales. This happiness, more about long-term life satisfaction than hedonism, is akin to what Aristotle and the Greeks meant by the term eudaimonia.

The United Nations Happiness Report presents overall “happiness” scores for most of the world’s countries. For 2012 Denmark, at 7.7, heads the list, while Togo, at 2.9 is at the bottom. The United States ranks seventeenth at 7.0, having dropped from eleventh (7.3) in 2007. Though most but not all (Costa Rica, for example, scores 7.3) of the world’s happiest countries are quite wealthy, happiness levels in the richest are generally flat, while many poor nations have seen great improvement in recent years (Angola’s score rose from 4.2 to 5.6), again illustrating that GDP growth is far more important for the poor than for the rich. Social insecurity has led to major drops in Greece, Spain, and Italy.11

The distribution of happiness within the population is equally important, if not more so. John Helliwell, a lead author of the UN Happiness Report, observes:

Among those countries with high average scores, some have quite high degrees in the distribution of happiness (e.g., Denmark and The Netherlands), while in some other fairly high-ranking countries (e.g., Costa Rica and the United States) there is much dispersion, and a higher portion of the population has low life satisfaction.12

Between objective well-being and subjective happiness lie what the model calls happiness skills, and these are the tasks of personal change.

While conditions of life matter greatly for personal happiness, our great religions and wisdom traditions, as well as modern positive psychology and neuroscience, teach us that proper attitudes and behaviors are also essential, and in more comfortable nations, even more important—as we have seen earlier in this book, individuals with a “materialistic” outlook on life are often unhappy, even when they are rich.

The attitudes and behaviors that constitute “happiness skills” include such things as gratitude, altruism (it is, indeed, better for happiness to give than to receive), kindness, sociability, delayed gratification, empathy, compassion, cooperation, and many other virtues which education can play a part in cultivating.

The beauty of this model in our view is that it does not ignore either the importance of policy or of personal behaviors in achieving good lives for all. It does not force us to choose between happiness and well-being, but recognizes that they are different ways of measuring our success. And it excuses neither widespread inequality nor a cavalier attitude toward the ecological limits of our biosphere. But it is not a call for sacrifice; indeed, the research behind the model implies that we can have a better life with less consumption in wealthy countries while allowing economic growth where it really adds to well-being and, at the same time, protecting our planet. The sacrifice is now; “getting and spending,” as Wordsworth put it, “we lay waste our powers.” In the pursuit of affluenza and in the name of limitless growth, we decimate our only planet for which there is no spare.

THE HAPPINESS INITIATIVE

As we see, putting two and two together, objective indices such as GPI can help us measure well-being more effectively. Internationally, many such excellent indices are being developed; one of our favorites is the Canadian Index of Well-Being, which uses a set of domains closely aligned to that of Bhutan.13 But for policy makers, such objective metrics are not enough. They must know not only if lives are improving objectively, but also whether people understand and appreciate the changes. If for instance, crime is falling, but people, fed a steady diet of TV crime shows, believe life is getting more dangerous, politicians may find themselves having achieved important successes but being cast out of office for their efforts. One of the solutions to this is to add a battery of subjective survey questions to measures like GPI, an idea which the state of Vermont calls “GPI Plus.”

In our view, one of the best of these surveys is the joint creation of a Seattle-based nonprofit called the Happiness Initiative (HI) and psychologist Ryan Howell at San Francisco State University, who also developed the Beyond the Purchase project described in chapter 22. When you take that survey (www.happycounts.org) online—it takes about 15 minutes—you receive an immediate life-satisfaction score and scores for each of the ten domains the survey measures (it includes the nine Bhutan domains, and adds a tenth, work satisfaction, whose importance for well-being has been made clear by the Gallup organization). Howell and a team of his graduate students did extensive testing of hundreds of survey questions from around the world to find the ones with the highest correlations to reported subjective well-being for the HI survey.

The survey can be employed by collectivities of people ranging from cities to colleges to businesses to determine their aggregate levels of happiness. “We have been working with cities—from Seattle to Eau Claire, Wisconsin; Nevada City, California; and many others, to help them determine the happiness of their citizens, to engage those citizens in discussing the results, and to develop programs or policies that can improve well-being,” says Laura Musikanski, the vibrant and articulate executive director of the Happiness Initiative. “We have also worked with more than a dozen colleges and universities to assess their student and staff happiness levels. On our website, we offer toolkits that allow all kinds of communities and organizations to use our survey effectively. Forty thousand people have already taken it.”14 (Their results are captured in easy-to-read graphs on the Happiness Initiative website.)

Measuring happiness and well-being will require us to draw from a plethora of good ideas and models out there in addition to GPI, and cull the best indicators from all of them. The ecological economists Robert Costanza and Ida Kubiszewski, both members of the International Expert Working Group advising Bhutan’s government, believe the time has come to “embark on a new round of consensus-building” to develop new economic goals and better measures of success that can replace the famous Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944, which ushered in the age unlimited growth without limit, the Age of Affluenza. “You might call it Bhutan Woods,” they say, suggesting that the nation that has championed the idea of a new development paradigm in the United Nations is the perfect place to hammer out the new plan. They’ve helped build a stunning new website and organization, the Alliance for Sustainability and Prosperity (www.asap4all.org), to promote the concept.

In due time, we believe, this widespread new interest in measuring what matters will help us take our affluenza temperature and record the most vital of our social and economic signs. You get what you measure, and we believe that if we start measuring the right things, we will use the information to make better lives.

A final caveat: Aggregate measures of subjective life satisfaction and contentment with conditions of life are important for societies, and together with objective data, can tell us how we are doing in meeting perceived human needs. But Prime Minister Thinley makes clear that what his country means by “happiness” is not merely a measurement of personal satisfaction, and certainly “not the fleeting, pleasurable ‘feel good’ moods so often associated with that term. We know that true abiding happiness cannot exist while others suffer and comes only from serving others.”