CHAPTER 5

Community chills

That which is not good for the beehive cannot be good for the bee.

—MARCUS AURELIUS

People are so fascinating that I love to sit at my computer and learn about them.

—TIME COLUMNIST JOEL STEIN

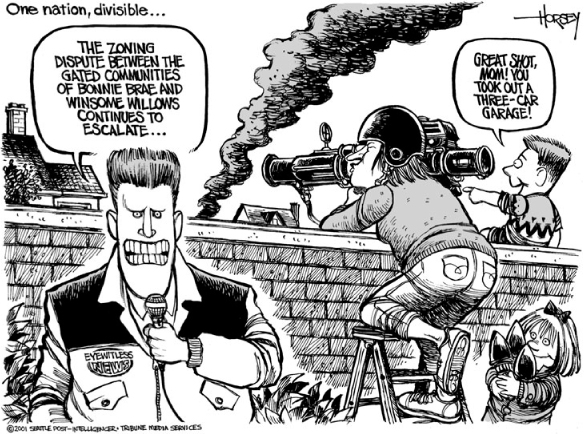

You may have seen the ad for an SUV, picturing a suburban street of expensive, identical ranch-style houses with perfect lawns. The SUV being advertised is parked in the driveway of one of them. But in every other driveway is … a tank. A big, deadly Army tank. It’s a stark, ironic ad, reminding us how chilling our communities have become as our war of all-against-all consumer competition continues. How much our sense of community has changed since the 1950s! Back then, Dave used to walk with his grandfather four or five blocks to the town square in Crown Point, Indiana. Everyone knew his grandfather, even the guy carrying a sack of salvaged goods. Half a century later Dave still remembers the names of his grandparents’ neighbors and the summer backyard parties they threw.

In the fifties, Americans sat together with their neighbors, cracking up at Red Skelton’s antics. In 1985, we still watched Family Ties as a family, but by 2013, each member of a family often watched his or her own TV—while also texting messages or talking with Siri, the iPhone robo-genie. Isolation and passive participation became a way of life. What began as a quest for the good life in the suburbs degenerated into private consumption splurges that separated one neighbor from another. We began to feel like strangers in our own neighborhoods—it wasn’t just the “Mad Men” who were ill at ease. Huge retailers took advantage of our confusion, expanding to meet our new “needs.” The more we chased bargains and the paychecks that bought them, the more vitality slipped away from our towns. Now, if we want to experience Main Street—the way it was in the good old days—we create a virtual identity on a website like Second Life or we travel to Disney World to visit faux communities where smiling shopkeepers, the slow pace, and the quaintness remind us that our real communities were once close-knit and friendly. How will Disney portray the good old days of the suburbs, in future exhibits? Will it orchestrate background ambience—highway traffic, jackhammers, and beeping garbage trucks—to make it more realistic? Will it re-create gridlock with bumper-to-bumper cars, complete with smartphones to tell our families we’ll be late for the next ride? Will our tour of the “gated community” require more tickets than rides through the “inner city” do? Will Disney hire extras to play the roles of suburbanites who can’t drive—elderly, disabled, and low-income residents, peeking out from behind living room curtains?

ALONE TOGETHER

Where can America’s stranded nondrivers go, in today’s world? There are at least twenty million Americans of voting age who don’t drive. There are fewer colorful cafés down the block, or bowling alleys or taverns, where neighbors can “be apart together, and mutually withdraw from the world,” in the words of writer Ray Oldenburg. Such “great good places” or “third places,” apart from both home and work environments, are disappearing or moving to the fake “neighborhoods” in megamalls.

“We’ve mutated from citizens to consumers in the last sixty years,” says James Kuntsler, the author of The Geography of Nowhere. “The trouble with being consumers is that they have no duties or responsibilities or obligations to their fellow consumers. Citizens do. They have the obligation to care about their fellow citizens and about the integrity of the town’s environment and history.”1

The Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam has devoted his career to the study of “social capital,” the connections among people that bind a community together. He observed that the quality of governance varies with the level of involvement in such things as voter turnout, newspaper readership, and membership in choral societies. He concluded that far too many Americans are “bowling alone.” (More people are bowling now than a generation ago, but fewer of them bowl in leagues.) Once a nation of joiners, we’ve now become a nation of loners. Only about half of the nation’s voters typically vote in presidential elections. Fewer are attending public meetings on town or school affairs, PTA participation has fallen dramatically since 1970, and fraternal organizations like the Elks and Lions are becoming endangered species.2

“We are not talking simply about nostalgia for the 1950s,” said Putnam in an Atlantic interview. “School performance, public health, crime rates, clinical depression, tax compliance, philanthropy, race relations, community development, census returns, teen suicide, economic productivity, campaign finance, even simple human happiness—all are demonstrably affected by how (and whether) we connect with our family and friends and neighbors and co-workers.”3 In other words, when consumption and profit are the guiding lights of a local culture, its best qualities are guaranteed to decline.

The jury’s out on whether the digital romance that’s swept us off our feet will make our communities and lives more satisfying in the long run. In the book Alone Together, Sherry Turkle observes a troubling irony: as a society, we settle for a digital illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship. “It used to be ‘I have a feeling, I want to make a call.’ Now it’s ‘I want to have a feeling, I need to make a call.’” Turkle quotes a twenty-six-year-old lawyer whose cell phone has become the center of her universe. “When there is an event on my phone,” says the young woman, “there’s a brightening of the screen. Even if the phone is in my purse … I see it, I sense it. I always know what is happening on my phone.” Venturing deeper into a digital forest, we see employees in staff meetings trying to text while still somehow making eye contact, and teenagers risking their lives (and ours) to check messages while driving (and in some cases, while dying). In recent news: the tragic and all-too-common story of sixteen-year-old Savannah Nash, on her first solo drive to the grocery store. She turned left off the highway without seeing an oncoming semitrailer truck. “There was a text message found on her phone that hadn’t been sent yet,” said the highway patrolman responding to the accident, adding that up to one-fourth of traffic accidents in the United States are now related to texting.4

AMERICA IN CHAINS

Another symptom of civic degeneration is the disappearance of traditional civic leaders of community organizations. Bank presidents and business owners with long-standing ties to the community are bounced from positions of community leadership when US Bank, Wal-Mart, Office Max, and Home Depot come to town to put them out of business. What do we get when the chains take over? Lower prices, cheaper stuff. But what we lose is a sense of belonging and a sense of cultural identity. At a locally owned coffee shop, you might see artwork by a friend who lives down the street. The shop is your coffee shop, and you stand a better chance there of coaxing neighbors to look up from their laptops to talk. At your independent bookseller, you’ll find books from small presses that publish a wider variety of books than mainstream publishers, and shopkeepers who actually know something about the books’ contents.

By using economies of scale in purchasing and distribution, and being able to stay in the market even at a loss, these monolithic retailers can drive out competition within a year and in some cases sooner. And we go along with it, for the lower prices—forgetting about the overall costs. In search of better buys and higher tax revenue, consumers and city council members typically first sacrifice Strip Avenue, then downtown, to the franchise developers, forgetting that much of a franchise dollar is electronically transferred to corporate headquarters, while a dollar spent at the local hardware stays put in towns or neighborhoods, as small businesses hire architects, designers, woodworkers, sign makers, local accountants, insurance brokers, computer consultants, attorneys, advertising agencies—all services that the big retailers contract out nationally. Local retailers and distributors also carry a higher percentage of locally made goods than the chains, creating more jobs for local producers. When we buy from the chains, instead of a multiplier effect, we get a “divider effect.” In virtually every economic sector, the franchises have divided and conquered the community-based, independent stores. Together, Home Depot and Lowe’s control 36 percent of the home improvement market. Starbucks and Dunkin’ Donuts have together knocked about half of the coffee shops out of business, and when it comes to books, Amazon and Barnes & Noble rule the roost, with 49 percent of the market share.5 With e-books making up almost a fourth of publisher sales in the United States, browsing in comfortable little bookstores is becoming a lost pastime. There’s only one location in America—a barren plain in South Dakota—that isn’t within a hundred miles of McDonald’s, and the top ten chain restaurants collectively grossed about $100 billion in 2012. Impressive, but compared to Wal-Mart, still small change. When your company’s annual revenue ($469 billion in 2012) equals about as much as America’s Medicare expenditures, that’s the big time.6 In a world where more than half of the world’s largest economies are corporations, Wal-Mart wields more power than most of the world’s countries. Fortunately, many US towns and cities are challenging that power.

AL NORMAN, SPRAWL BUSTER

Twenty years ago, Al Norman spearheaded a Wal-Mart resistance campaign in his hometown—Greenfield, Massachusetts—and won. After his story appeared in Time, Newsweek, the New York Times, and 60 Minutes, “My phone started ringing and hasn’t stopped,” he says. “I’ve been to most of the states now, teaching hometown activists what tools are available.”7 He’s still on the Wal-Mart beat, and his Sprawl Busters website lists success stories from 440 towns and cities that have prevented unwanted invasions of big-box stores. Norman has personally coached many of these to victory, but he’s also very familiar with the defeats and the impacts that can follow. “A classic example is the small town of Ticonderoga, New York,” he says. “The local newspaper documented that in the first eight months of Wal-Mart occupancy, business fell by at least 20 percent at the drugstore, jeweler, and auto parts stores. But the game was totally over at the Great American Market, the town’s only downtown grocery store. First they cut their operating hours, then dropped the payroll from twenty-seven people to seventeen. It wasn’t long before the grocery closed completely. Many of the people who shopped at the GAM were the elderly, low-income people without access to a car.”8

“I’ve been here twenty-five years,” a downtown Sunoco station owner told Norman. “On the week before Christmas in prior years, you couldn’t find a parking space on this street. This year, you could have landed a plane on it.” Says Norman with no lack of candor, “Instead of being a shot in the arm to the economy, Wal-Mart has been like a shot in the head.” He compares Wal-Mart with Publix Supermarkets, owned by its 152,000 employees. Publix operates an employee stock ownership plan that programmatically distributes company stock at no cost. It also has a group health, dental, and vision plan as well as company-paid life insurance. “Unlike Wal-Mart,” says Norman, “Publix has been listed for the past fifteen years in Fortune magazine’s 100 best companies to work for. You won’t find Wal-Mart on that list, because Wal-Mart has more employee-based lawsuits than men’s suits. At every link in the chain, someone is being exploited, from Shenzhen, China, to Sheboygan, Wisconsin.”9

In 2013 our social defenses were down. Distracted by material things and out of touch with social health, we watch community life from the sidelines. Hurrying to work, we see a fleet of bulldozers leveling a familiar open area next to the river, but we haven’t heard yet what’s going in there. Chances are good it’s a Wal-Mart, McDonald’s, or Starbucks.

SOCIAL SECESSION

What happens when affluenza causes communities to be pulled apart (for example, when a company leaves town and lays off hundreds of people), or crippled by bad design? We “cocoon,” retreating further inward and closing the gate behind us. Across the United States, at least 10 percent of this country’s homes are in gated communities, according to Census Bureau data. (Including secured apartment dwellers, prison inmates, and residential security-system zealots, at least one in five Americans now lives behind bars.)

“We are a society whose purported goal is to bring people of all income levels and races together, but gated communities are the direct opposite of that,” the sociologist Edward Blakely writes in the book Fortress America. “How can the nation have a social contract without having social contact?”10 Robert Reich observes, “Across the nation, the most affluent Americans have been seceding from the rest of the nation into their own separate geographical communities with tax bases (or fees) that can underwrite much higher levels of services. They have relied increasingly on private security guards instead of public police, private spas and clubs rather than public parks and pools, and private schools. Being rich now means having enough money that you don’t have to encounter anyone who isn’t.”11

In 1958, trust was sky high. Seventy-three percent of Americans surveyed by Gallup said they trusted the federal government to do what is right either “most of the time” or “just about always,” a number that plummeted to just 19 percent in 2013. The slogan of the popular 1990s TV series, The X-Files, was “trust no one,” and Americans have taken that cold advice to heart. Yet, as Putnam writes, “When we can’t trust our employees or other market players, we end up squandering our wealth on surveillance equipment, compliance structures, insurance, legal services, and enforcement of government regulations.”12

QUEASY

If an eight-year-old girl can walk safely to the public library six blocks away, that’s one good indicator of a healthy community. For starters, you have a public library worth walking to and a sidewalk to walk on. But more important, you have neighbors who watch out for each other. You have social capital in the neighborhood—relationships, commitments, and networks that create an underlying sense of trust. Yet in many American neighborhoods, trust is becoming a nostalgic memory. Seeing children at play is becoming as rare as sighting an endangered songbird. After a horrifying string of mass shootings in US schools, 62 percent of parents of school-aged children now want to hire armed guards at schools. Meanwhile, the $34-billion-a-year gun industry is on a roll: annual background checks by firearms vendors have doubled since 2006.13

Here’s one bizarre yet fairly common indicator of our queasiness: a high percentage of recently deceased people request to remain in touch with their cell phones, for all of eternity. Funeral directors report that in effect, dying doesn’t have to mean hanging it up. Says Noelle Potvin, a funeral home counselor for Hollywood Forever, “It seems that everyone under 40 who dies takes their cell phones with them. A lot of people say the phone represents the person, that it’s an extension of them, like their class ring.”14

COOPERATION VERSUS CORPORATION

Local buying and investing has become a very potent antidote to affluenza and the profiteering it spawns. Like acupuncture or a herbal remedy, the localization movement is precise, preventive, and in tune with changing times. Corporations are often ill-equipped to customize their products and services to meet regional needs. For example, local banks can better assess the risk of a loan, and local independent groceries can better meet specific ethnic demands. Small businesses can be more personable and responsive as the economy continues to shift toward services and experiential spending. Take the food industry, a great example of localization. Although 70 percent of the American diet is processed food, and the American landscape is dotted with 100,000 McDonald’s and other top-ten fast-food restaurants in the United States, companies like Whole Foods Market and Organic Valley (a farmer-owned cooperative) are leading the charge back to food that keeps us healthy. A champion of local food, Alice Waters, writes, “When we eat fast-food meals alone in our cars, we swallow the values and assumptions of the corporations that manufacture them. According to those values, eating is no more important than fueling up, and should be done quickly and anonymously.” Yet food is far more than that; throughout human history, it was a way to come together, to express our identity, and to be rooted in the earth. Food delivers not just physical health, but also social health. “At the table, we learn moderation, conversation, tolerance, generosity and conviviality; these are civic virtues,” says Waters.15

A GEOGRAPHY OF NOWHERE?

Have we become a nation too distracted to care? Like the medium-size fish that eat small fish, we consume franchise products in the privacy of our homes, then watch helplessly as the big-fish franchise companies bite huge chunks out of our public places, swallowing jobs, traditions, and open space. We assume that someone else is taking care of things—we pay them to take care of things so we can concentrate on working and spending. But to our horror, we discover that many of the service providers, merchandise retailers, and caretakers are not really taking care of us anymore. It might be more appropriate to say they’re consuming us.