THREE

Culture and Identity in Mentoring

Culture lives in the collective. It is the combined customs, arts, social institutions, and achievements of a particular nation, people, or other social group and is reflected in the behavior, beliefs, and outlook of a group of people. Identity is individual, made up of who we are individually and how we see ourselves in the context of society and the world. Our own identity may draw from many cultures and may or may not reflect the archetypical beliefs that categorize the cultures with which we identify. Every individual interprets and adapts cultural influence differently. Exploring your identity requires looking at how your own culture has impacted you. So first, let’s talk about culture.

Culture and Interpersonal Relationships

Most people associate culture with things like food, music, religious traditions, and celebrations. Indeed, these are reflections of culture, but there is much more that categorizes a culture than these objective elements. Each culture shares language, educational, philosophical, and religious systems, and values, laws, and unwritten rules of conduct that influence behavior, beliefs, and outlook.

In Riding the Waves of Culture, management experts Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner explain that “culture is the way in which a group of people solve problems and reconcile dilemmas.”17 They suggest five ways that different cultures address interpersonal relationships that we find particularly relevant to the framework we describe in this book.

1. Applying Rules: Universalism and Particularism

Cultures that tend toward universalism approach problems as absolute and universally applicable (that is, the same rules apply to everyone). Cultures that tend toward particularism place far greater emphasis on relationships and unique circumstances (that is, different rules apply in different contexts). Imagine the judgment that someone at one end of the spectrum might apply to someone at the other end. A person who is universalistic might say of someone who is particularistic: “That person is shady. He won’t hold his own brother to the same rules as everyone else.” On the opposite end of the spectrum, someone who is particularistic might say: “That person is shady. He won’t even bend the rules for his own brother!”

2. Role of the Group: Individualism and Communitarianism

Individualist cultures focus first on individual contributions, while communitarian cultures focus on the community first. In a communitarian culture, individual achievement can often be perceived as selfish or disrespectful. In an individualistic culture, however, it is expected that one would first look after their own needs and then those of the community. In this case, someone who tempers their own achievement so as not to stick out from the crowd may be viewed as lazy, cowardly, or unduly passive.

3. Role of Emotions: Neutral and Affective

A neutral culture places more value on being detached, objective, and unemotional. In an affective culture, lack of emotional expressiveness is seen as being too dispassionate, or even as uninterested. Neutral cultures view the expression of emotion as a weakness. Anger or intense emotions are viewed as unprofessional and signal a lack of objectivity. This attitude was made explicit in the famous line from the movie A League of Their Own: “There’s no crying in baseball!” It is still the unspoken rule in mainstream US business culture (and in fact that line in itself is reflective of a culture clash). In affective cultures, however, expressing emotion is a sign that you are invested in the outcome and in the relationship. Lack of expressiveness can be viewed as a lack of interest.

4. Scope of Relationship: Specific and Diffuse

Some cultures see relationships as limited to a specific topic (such as focusing only on work-related goals, common in mainstream US business culture), while other cultures are more diffuse, requiring a broader, whole-life perspective (such as how to balance work and life priorities). Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner explain that “doing business with a culture more diffuse than our own feels excessively time consuming. . . . In diffuse cultures, everything is connected to everything. Your business partner may wish to know where you went to school, who your friends are, and what you think of life, politics, art, literature and music. This is not a waste of time, because such preferences reveal character and form friendships.”18

5. How Accomplishment is Measured: Achievement and Ascription

In cultures aligned with achievement, people are judged by what they have accomplished. In cultures aligned with ascription, people are judged by the status attached to certain aspects of their identity, who they are (family, age, birth, gender), by their connections, and by their educational record. “In an achievement culture,” Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner explain, “the first question is likely to be ‘What did you study?’ In a more ascriptive culture, the question will more likely be ‘Where did you study?’ “19

» YOUR TURN «

1. Place an “✗” on each continuum where you see yourself on Table 3.1. Place a checkmark (✔) on each continuum where you see your culture of origin. Place an asterisk (*) where you see your organizational culture. Then answer the questions that follow.

TABLE 3.1 Where are you on each cultural continuum?

Universalism |

How we apply rules |

Particularism |

Same rules apply to everyone Rules trump relationship |

|

Rules differ based on relationship |

Individualism |

Role of the group |

Communitarianism |

Focus on individual needs, goals, and objectives over group |

|

Focus on group needs, goals, and objectives over individual |

Neutral |

Role of emotions |

Affective |

Control or suppress emotions |

|

Express or demonstrate emotions |

Specific |

Scope of relationship |

Diffuse |

Workplace conversations limited to work issues or specific topic |

|

Workplace conversations cover many aspects of life |

Achievement |

How accomplishment is measured |

Ascription |

Status derived from doing and achievement |

|

Status derived from being, your attributes, and connections |

Source: © 2019, Center for Mentoring Excellence

2. How do the factors you discovered in the continuum table affect your work relationships?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. If there is a difference between where you see yourself and where you see your organizational culture, what impact does that difference have on your work life?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Identity Iceberg

Your culture is an intricate combination of the environmental factors that shaped you, but your identity is you: the way you think about yourself, the way you are viewed by the world, your personality, and the characteristics that you and others choose to define you. Identity consists of both the simple facts about you (such as your name, where you live, your height and weight) and more complex elements (such as your culture, your gender identity, your motivation, your religious beliefs and values).

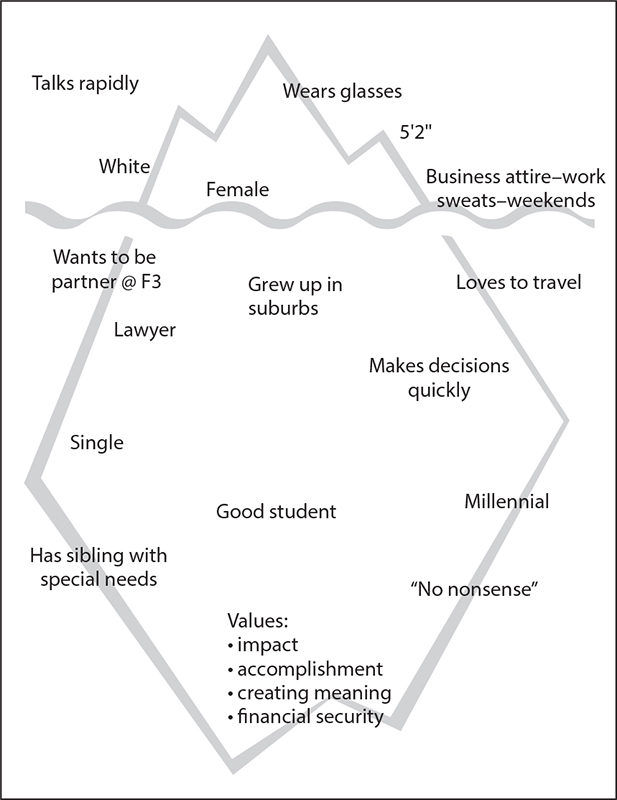

We like to think of identity as an iceberg: about 20 percent of our identity is visible to the world, and 80 percent of its substance is below the waterline, invisible at first glance. All the elements of our identity shape how we show up in the world, how we view the world, and how the world views us. For example, if Mia and Christopher were to complete their own icebergs, they might look like Figures 3.1 and 3.2.

When you think of the elements that make you you, you might think of things you can see, the visible 20 percent (gender expression, skin color, age, physical ability), or of things you can’t see but which lay just beneath the surface (ethnicity, national origin, religion, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, political beliefs, education level, and life experience). What you probably don’t consider are two significant components of every individual’s iceberg: what motivates you and what you value. These always lie below the waterline, sometimes so deep that we are not fully aware of how these factors impact us until we spend time reflecting on it. It is this reflection that is essential to preparing yourself for your mentoring relationship.

FIGURE 3.1 Mia’s Iceberg

FIGURE 3.2 Christopher’s Iceberg

» YOUR TURN «

Take the time to reflect on your own iceberg. Draw your iceberg if that makes it easier.

1. What elements of your identity are readily visible to other people?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. How does your iceberg impact how you relate to others?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. How does your iceberg impact how others relate to you?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

4. Name at least three elements of your identity that people cannot see that impact your view of the world.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

When we think of our identity, we often get stuck on the visible 20 percent and forget about other characteristics, styles, and preferences that influence us. Two key below-the-waterline factors that often influence mentoring relationships are motivation and learning style.

Motivation

In a mentoring relationship, it is essential to understand what motivates you to show up at work every day and what motivates you to participate in mentoring. You can determine this by reflecting on questions like: Why do I work? What sort of work do I hope to have? What impact do I hope to have on the organization and the people I work with?

Many studies have shown that the meaning people give to work and the drivers of employee engagement are similar across generations, yet the meaning that people give those factors varies by generation.20 For example, although all generations seem to seek a sense of purpose in their work, baby boomers (born 1943–60) tend to focus on achieving an impact within the organization. In contrast, millennials (born 1981–2000) look for work that will help them achieve a sense of purpose in the greater social context. Building a career is a primary motivator for baby boomers and Gen Xers (born 1961–80), while millennials seek more to craft a life that integrates work with interests outside of work. Baby boomers are typically motivated by perks and public recognition.21

Gen Xers tend to value freedom and can be motivated by time to pursue other interests or have fun at work.22 Millennials are typically motivated by the chance to make an impact, have a career path, and get feedback on their learning.23 The postmillennial generation (sometimes referred to as Gen Z or iGen), those born after 2000, enter the workplace with an entrepreneurial and global mindset.24

They are highly diverse and multicultural, therefore likely to actively seek learning opportunities such as mentoring for the sake of garnering more life experiences.25

What motivates someone depends on more than just their generation, of course; it varies by individual based on other factors as well. For example, we once met a young attorney who was passionate about her desire to help refugees and immigrants. After law school she went to work in a large law firm to get experience in complex cases and earn enough to pay down her law school loans. She intended to work in the firm five years and then parlay her skills to do legal work on behalf of immigrants and refugees in the public sector. She looked for a mentor at the firm but could not find one who seemed to understand that she did not want to become partner and wasn’t motivated by the same things as her generational peers. Every time she approached a potential mentor, their guidance would be to learn how to develop a book of business or to position herself with influential partners who could help her develop client relationships. Yet this woman’s motivation was not aligned with the guidance.

Take a few moments now to reflect on what motivates you.

» YOUR TURN «

1. What motivates you to show up for work each day?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. When have you felt most motivated to set and achieve goals?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. What is your vision for yourself in three years? Five years?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

How Identity Impacts Motivation for Mentoring

Your motivation for being a mentor or mentee definitely impacts the mentoring relationship. There are many reasons why mentors choose to mentor and many reasons why mentees opt for mentoring. Mentors may have specific knowledge they want to pass on to others. They may find joy and reward in helping others learn, or they might want to pay it forward. Mentees may have their sights set on advancing in their organization, shifting their career path, or expanding their networks. Both mentors and mentees may get energized by learning from others different from themselves. They may see mentoring as a personal growth and development opportunity. They may want to mentor or be mentored by a specific person. Mentoring might be a performance requirement or leadership responsibility.

Christopher had recently become more attuned to how things were for women in the workplace, and he viewed mentoring as a chance to pay it forward for his two grown daughters. The two mentors whom you will meet in later chapters, Heather and Darren, were motivated for other reasons. Heather’s motivation was to pave the way for the next generation of women leaders so that it would be easier for them to make their mark and achieve their potential. Darren viewed mentoring as part of his leadership responsibility. He was committed to strengthening the leadership bench in his organization.

Mentees’ motivations also vary. They may come to mentoring through compliance to a performance requirement. They may be seeking to emulate a role model or desire to learn from someone with specific experience, expertise, or talent, as in Mia’s case. Heather’s mentee, Aesha, sought mentoring as a personal growth and development opportunity. Others may just enjoy the collaborative learning that results from mentoring; or they may want to develop a more global mindset. Mentees who identify with groups that are traditionally underrepresented in the workplace (including people of color, LGBTQ, people with disabilities, and, in many industries, women) tell us that they want to participate in mentoring because they want to increase their exposure and access to more senior people in the organization, and they want to enhance their image in the organization by developing a relationship with someone more senior who can attest to their strengths.

» YOUR TURN «

1. What is your motivation for engaging in mentoring?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. What do you hope to gain as a mentor or a mentee?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Exploring Differences in How We Learn

Learning is the focus of mentoring. When we train new mentors and mentees, we spend some time helping them discover and understand their learning styles. In training, we often use the 3.1 version of David Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory (LSI).26 Kolb’s LSI focuses on how people perceive and process information, and how we prefer to solve problems, make decisions, manage disagreement, and take in information.27 While there is some debate in the learning community about the strict validity of learning styles, experiential observations show their practical utility, so it’s worth contemplating the questions below.

Kolb’s LSI asks you to answer such questions as the following: How do you best take in and process information? Do you need to reflect on information before you take action? Do you learn best by reflecting alone and then sharing your ideas and feelings? Do you perceive information abstractly and then need time to process it and think things through in an organized, rational, data-based manner? Are you more comfortable with a decision that comes from consensus, or do you prefer to reflect on data? Do you perceive information abstractly and process it actively and quickly to find a concrete solution? Do you prefer practice application, or strategic thinking and planning, rather than discussion and consensus building? Do you learn by trial and error? Are you a creative problem solver, risk taker, and change agent? Do you adapt easily to new situations?

We’ve adapted the chart below (Table 3.2) to help you think about how you learn and interact with others. People demonstrate characteristics in all four quadrants but generally prefer one quadrant or the other. The quadrant that resonates the most may shift depending on the context in which the learning takes place.

For example, Mia has a converging learning style. She reaches decisions quickly, sometimes lacking full information. She is viewed by some as making decisions hastily, without taking all factors into account. For people with a converging learning style, the purpose of a meeting is to reach a decision and get things done. Christopher, in contrast, likely has a diverging learning style. People with the diverging learning style seek consensus. They like to build relationships before making decisions, and they often see the purpose of meetings as getting people’s viewpoints and opinions rather than reaching a decision.

Mia wanted to dive right into goal achievement and was surprised that Christopher wanted to build their relationship first. She found it confusing and even unsettling that he was unwilling to engage right away on her career goals. Christopher felt that Mia was rushing the process and wondered if it was an indication that she valued the outcome over the opportunity to build a relationship. In fact, he was right: for Mia, the time spent on building a relationship seemed like a waste of time.

TABLE 3.2 Selected learning-style descriptors

Accommodating |

Diverging |

Energizing people |

Motivating the heart |

Visioning |

Being imaginative |

Motivating |

Understanding people |

Taking risks |

Recognizing problems |

Initiating |

Brainstorming |

Getting things done |

Being open-minded |

Being adaptable and practical |

Valuing harmony |

Converging |

Assimilating |

Exercising personal forcefulness |

Using principles and procedures |

Solving problems |

Planning |

Making decisions |

Creating models |

Reasoning deductively |

Defining problems |

Valuing efficiency and timeliness |

Developing theories |

Being practical |

Being logical |

Setting goals and timelines |

Deciding with data |

Source: Adapted from Zachary with Fischler, The MenteeS Guide, 36.

If more than one learning style seems to resonate with you, ask yourself: When it comes to making decisions, are you more focused on action or reflection? If you focus on action, you are more likely to have a converging learning style or an accommodating learning style. If you tend to reflect, you are more likely have a diverging or assimilating learning style. In order to feel comfortable with a decision, which of these is more important to you: to know how people feel about the decision, or whether the data support the decision? If you focus more on people, you are more likely to have a diverging or an accommodating learning style. If you value data more when making decisions, you are more likely to have a converging or assimilating learning style.

Once you become aware of your own learning preferences, you can think about the judgments you may be making about people with learning styles different from your own. For example, we often hear from those with diverging learning styles that converging learners come across as too blunt, too quick, and too judgmental. Assimilating learning styles are often perceived by others as too cold or too data- driven, and those with accommodating learning styles as too hasty. Similarly, assimilating learners see diverging learners as spending too much time seeking consensus and checking out others’ feelings. Recognizing the judgments we make about others tells us a lot about ourselves. Reflecting in this way helps increase self-awareness about how we take in and process information. In a mentoring relationship, discuss your learning style and that of your mentoring partner’s. This helps you both learn more effectively during your mentoring partnership.

We do not live in a world where we operate alone. Culture and identity have a huge impact on us and on how others see us. Creating awareness around identity and culture is critical to the mentoring process, and to understanding what makes up our view of ourselves and what shapes our view of the world. In the next chapter, we’ll complete our look at self-awareness preparation with an exploration of bias and privilege in mentoring.

» YOUR TURN «

1. Look at the learning style descriptors chart (Table 3.2). Which learning style do you most seem to prefer?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. What are some of the judgments you make about people who exhibit other learning styles?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. Which learning style might challenge the way you prefer to communicate with others?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Chapter Recap

1. Becoming more self-aware is the necessary first step to bridging differences. Without it, you will not be able to identify or understand when you encounter differences that matter.

2. Our culture, background, and identity shape our worldview and how we show up in the world. Only about 20 percent of our identity is visible to others. The 80 percent that lies beneath the surface has a lot to do with how we think of ourselves and act in the world.

3. Once you start to understand what elements of your identity make up your worldview, you’ll be better equipped to recognize and understand when and where your mentoring partner’s view is different.

4. Keep in mind that two people who come from similar cultures may express their culture differently. Once you have a sense of where you are on various cultural continua, you’ll be better able to see how your culture influences how you see the world and how others in your world see you.

5. Learning style can influence how you see others and how others perceive you. Understanding your learning style and your mentoring partner’s learning style will help you both learn more effectively during your mentoring partnership.