EIGHT

Enabling Growth

Enabling growth is the longest of the four phases, the heart of mentoring, and by far the most exciting and challenging work you will do together. The preparation you’ve been working so hard on—to this point, preparing yourselves, and then setting the parameters of your mentoring relationship—position you and your partner for success.

This next phase offers a tremendous opportunity for learning and development, yet it is also when mentoring partnerships become most vulnerable to derailment because it requires the biggest investment of time, energy, and sustained momentum in order to see results. Mentorship is a living, evolving relationship. Keep it fresh and moving forward by continually monitoring your progress and celebrating learning milestones to create the momentum you need to successfully accomplish your mentoring goals.

Early on, Martin was struggling with how to explain the way his family’s story had guided him and why he felt that getting where he wanted was going to be such a struggle. As it turned out, Darren made it easy for him. At their next meeting, Darren asked Martin if he’d given any more thought as to why he was so doubtful about his capabilities. This time Martin didn’t hesitate in responding.

Martin told Darren that he had been receiving a lot of flak lately from management. “They appreciate that I hit my numbers. They really do. They’ve told me so. But every time I offer suggestions or ask questions about how we can improve processes and procedures, I get pushback. In fact, they seem irritated.”

Darren probed for more specific examples. Martin told him that he had suggested a new spreadsheet for tracking productivity at a recent team meeting. Several managers were obviously annoyed and told him that he was being insubordinate by not following the proven procedures they had laid out for him. Martin’s intent had been to identify a more efficient way, not to disregard established procedure, but he hadn’t been given a chance to say so. Darren understood why Martin would be upset. Maybe Martin was resenting what he felt were arbitrary rules that were designed to keep him quiet.

Martin continued. “And there’s more—the performance improvement plan that my manager put me on. Frankly, I’m embarrassed to talk about it. It upset me when I got it and I’m still upset about it.” It was clear Martin felt he had been evaluated unfairly, and the items he had been dinged on were things he couldn’t do anything about. Working in manufacturing had been great for Martin as he worked his way through school, but he knew he could contribute more and was ready to prove himself in a new challenge. Martin felt he could accomplish bigger things but was not sure what they might be. Now he was worried that he would never be able to move out of manufacturing. He couldn’t see a path out and felt like he was being kept down in a position that was beneath his ability, and maybe now he was even being forced out.

Getting Unstuck

Martin was stuck and Darren was stymied. Why Martin was stuck remained a mystery. Martin seemed to have a fixed mindset (see Chapter 2) about the possibility for change. Darren didn’t have any idea how to direct Martin, and he certainly couldn’t just tell Martin to figure it out himself. Darren knew he had authority to communicate directly with plant leaders on Martin’s behalf, but should he? How could he best facilitate Martin’s growth and development? He found himself stuck too.

Darren wanted to be supportive, but first he needed to understand where Martin was coming from. What was he missing? Darren wanted to know what it was like for Martin on a day-to-day basis, and what “arbitrary rules” were holding him back and in what ways. What was keeping Martin from raising concerns with his supervisor? What was it that Martin really wanted to do anyway?

As Darren got curious about Martin’s thinking, he knew that he needed more information to understand who Martin was and what truly motivated him. He wondered whether Martin’s motivation and capabilities were really aligned. One way Darren could help Martin get unstuck was to help Martin see how he could grow, and how he could take ownership of his work situation. But in order to do this, Darren needed to have a sense of where Martin should focus his energies. One concept that might have helped speed the process for Darren is something called native genius.

Working with Native Genius

In the book Multipliers, Liz Wiseman defines “native genius” as “something that people do, not only exceptionally well, but absolutely naturally.” She explains: “They do it easily (without extra effort) and freely (without condition). . . . They get results that are head-and-shoulders above others, but they do it without breaking a sweat.”66 We’ve found this concept particularly helpful in assisting the mentors we work with. In a very real sense, good mentoring is genius making. When mentors are able to help their mentees identify their native genius, understand it, and cultivate it, transformation happens. Kristen Wheeler, founder and creator of the Native Genius Method, describes native genius this way:

[It is] the meeting of what you’re good at and what you enjoy doing. What’s even more important is that Native Genius consists of actions you do on autopilot that you may not realize you’re doing—that’s the “native” part. The “genius” part is that others are noticing and valuing those actions because they’re above and beyond. Others are impacted by the special, shimmery quality of your Native Genius Actions. However, because these actions are on autopilot for you, you likely feel them as quite ordinary and think that anyone could do them. You may not even notice that you’re doing them at all! This is why most of us tend to overlook and undervalue our own Native Geniuses. We also underestimate how good we are at them. Then we discount them further because we enjoy them, especially if we’ve learned that “real work” shouldn’t feel good.67

When we step into our own native genius, we position ourselves for growth. We start looking for opportunities that allow us to repeat the behaviors that capitalize on our motivation and competence. We get better at what we do and get better results. Here’s how Darren helped Martin identify his native genius.

Darren decided to ask Martin some probing questions to help identify where Martin’s native genius lay. He asked, What do you like to do at work? What do you think you do best at work? When are you at your easiest, freest, and most productive? What drags you down?

In response to Darren’s questions, Martin started to describe the things in his job he thought he did best. “Well,” he said, “I am really good at holding my team accountable to metrics even though it’s not my favorite thing. It drains me to follow procedures that I don’t think are efficient, but if you give me a goal, I’ll hit it.”

“What else?” Darren could see that Martin had something percolating.

Martin smiled. “I do love finding new ways to motivate my team. I can read people fairly well and see what is going to get them to do the job well. We have team meetings every Monday, where we share stories and successes, and I always have a fun little game or something. I spend a bunch of time on the weekend thinking through what I’ll do with them on Monday. And on Sunday nights, I look forward to seeing what my team thinks.”

As Martin described this last strength, his eyes lit up and his voice became higher and more emphatic and energetic. Darren knew that there was something there that they should follow up on. Martin’s native genius lay in motivating people, and he was clearly good at it. Martin didn’t like rules and being forced to be accountable. He was spending too much time on something he was good at but did not enjoy (meeting numbers using the company’s current procedures). Darren was reminded of something he had heard his own daughter say not too long ago: “Just because I can do something, doesn’t mean I should.” Martin’s growth opportunity depended on spending more time in his area of native genius.

“Aha!” Darren said to Martin. “Now we’re getting somewhere!”

Action Strategies: Delegate, Delete, Contain

Too often, we spend time on the things we know we are good at just because we know we can do them, but they are not necessarily things we enjoy or even the best use of our time. We’ve identified three options for dealing with those things we are good at, but that drain our energy: delegate, delete, or contain. Here, too, native genius can come to the rescue.

More often than not, once we have defined our native genius, opportunities to delegate in those areas arise spontaneously. We see that others are willing and capable of taking on non–native genius tasks, freeing us to move on and focus on work we do prefer. Another strategy is to delete—to just stop doing some things altogether. When neither delegation nor deletion is an option, a helpful strategy is to contain those tasks: schedule a time to complete the more boring tasks so that you can focus on the good stuff.

Find Your Native Genius

You don’t have to wait for a mentoring relationship to find your own native genius. Begin by looking for the intersection of what you do best and what you most like to do. Ask yourself the same sorts of questions Darren asked Martin—your answers may surprise you. Build on your strengths; discover what excites you and what you enjoy. At the same time, be aware of things that drain your energy. If there is something you are good at but don’t enjoy, is there an opportunity to teach it to someone else or to delegate that task? Look for opportunities to build on what you love, not what you think you “should” be doing.

Mentors, this is a great opportunity to utilize what you learned about your mentoring partner earlier on. Reflect on what you learn about what motivates your mentee and what your mentee’s values are. These will guide you to ask questions that can help them discover their native genius. You can leverage difference by using what you know about your mentee to ask probing questions. How does what they do align with their values? How does it align with their strengths? Do they have an opportunity to act within the zone of appropriateness described in the last chapter? Let’s find out what was next for Darren in motivating Martin to find his native genius.

Darren felt more prepared at his next mentoring meeting with Martin. He knew that he needed to get Martin to become self-reflective and to understand where his ability and desire intersected. Cautiously, Darren set the stage for his probing questions, reviewing the purpose of the mentoring relationship and restating the ground rules around confidentiality. He began by framing the purpose of the conversation that he hoped was about to take place.

“I think you may be stuck,” Darren told Martin. “I need to better understand what’s going on for you, what you are good at and what you enjoy. I’m hoping you’ll be open and honest so that we can explore ways to get you unstuck.”

Darren wasn’t surprised that it took Martin a while to warm up to the conversation. He allowed all the time Martin needed, and paced his questions to encourage him. The extended conversation that ensued turned into the most honest and open conversation the mentoring pair had had thus far.

Learning about native genius is not just an exercise for mentees. Mentors will also find it instructive as they reflect on their own desires and competencies in their mentoring and leadership roles. Through these conversations with Martin, Darren could see possibilities for his own growth and development.

As Darren realized that Martin felt powerless to change, and had lacked the opportunity to claim ownership for his own growth and development, Darren too became aware of his own limitations. He could see that mentoring was going to be a development opportunity for himself as well. He would need to hone his own mentoring skills to foster that same sense of ownership in Martin. He was going to have to learn how to ask different questions, ones that were more probing, supporting, and challenging. He might also need to sit back and consider how to do a better job of putting his own native genius to work.

» YOUR TURN «

1. When you are energized and excited at work, what are you doing?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. What are you good at?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. Where does what you do well and what you love intersect? Use your understanding to guide your mentoring conversations and movement forward.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

4. What do you do at work that blocks your productivity and excitement?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Expanding Your Perspective

It is exciting to discover your own motivations and capabilities, and to help others discover theirs. Once you do, however, the question arises: Now what? As mentor or mentee, the answer is the same: You must take action. How can you help yourself or someone else take charge of their learning?

Engage in some serious self-reflection. Too often we are locked into our own cultural orientation, a particular way of viewing others’ strengths and limitations. Try to determine the nature of the cultural lens you are looking through by asking yourself:

» Why am I seeing things so differently than my mentoring partner?

» What is shaping the way I am seeing things?

» What cultural lens is my mentoring partner looking through that is shaping what they see?

Then go deeper by exploring the answers to the following questions:

» How might someone else see this situation?

» If this situation is the opposite of what I believe is true, how might someone else see it?

» If someone didn’t have the same knowledge that I possess, how might they see this situation?

Remember, you are looking to expand your perspective and explore what you might be missing. After you’ve done this work, seek to bridge differences by communicating to your mentoring partner, “Here’s what it’s like for me. How is it different for you?”

» YOUR TURN «

1. What more would you like to learn about your mentoring partner?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. What have you learned lately about yourself?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

If you or your mentoring partner has discovered an area of native genius that seems exciting but are having trouble figuring out how to get started, this is another area for deep reflection. Look for cultural differences between mentor, mentee, and workplace culture that may actually be standing in the way of forward movement. Questions for both mentees and mentors might include the following:

» What’s stopping you/me from taking charge of this interest? Could there be a cultural issue I’m not seeing?

» Do I/you feel that people higher up in the organization would have issues if I/you moved into this area?

» What is one easy step I/you can take to make this interest a reality at work?

» What is stopping me from supporting my mentee to take action on this?

» What is stopping me from talking to my mentor about my inability to get started on this?

Building Cultural Competency

Martin was working on motivating his team and thinking about delegation—he had a hard time not doing everything himself just to get it done quickly. This was a longstanding issue for him, and it had bubbled up before with his supervisor and never been fully addressed. It was clear to Darren that Martin would not be able to move forward until it was resolved.

The more Darren and Martin learned about each other, the more they began to realize that there were some fundamental differences in the way they viewed their own roles at work, in their motivations, and the way they saw the potential for opportunities. Early on, as they were sizing each other up, they were judging those differences. Darren thought that he’d like to get Martin to think more like him because it would create more opportunities for Martin. Martin was thinking that Darren’s view of the world might be better career-wise, but it didn’t resonate with him.

Over time, they stopped judging these different approaches. They started to see where there were commonalities in their thinking and to appreciate where there were differences. Now the challenge was how to make the most of those differences so that they could get the mentoring results they were seeking.

The key is in how each person in the mentoring relationship views differences.

The Intercultural Development Continuum

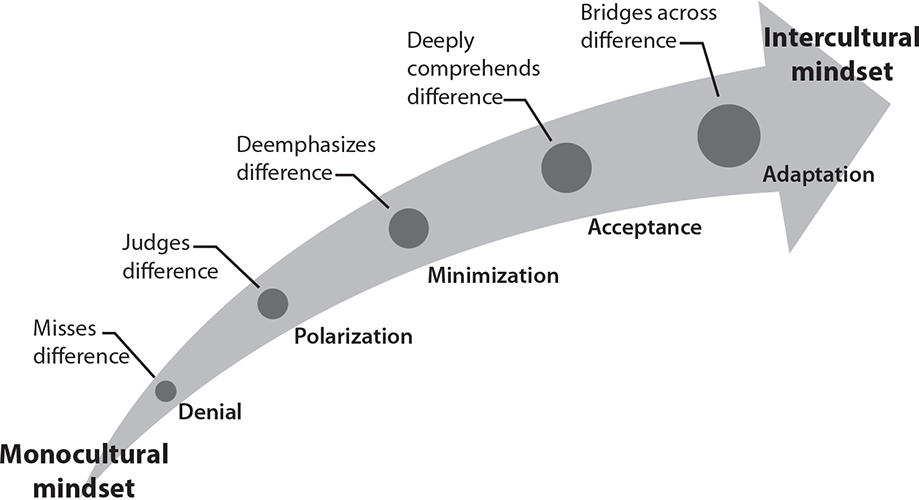

For more guidance on how to address differences, we focus on the first five stages of sociologist Milton Bennett’s cultural competency developmental continuum, which spans monocultural mindset to intercultural mindset (Figure 8.1).68 These are denial, polarization, minimization, acceptance, adaptation. We like this model for several reasons. First, it helps mentoring partners understand how they are viewing the differences between them. Second, it provides guidance on what to do to progress and develop. Third, it can serve as a diagnostic tool when there is lack of understanding. The only way to learn how to bridge difference is to go through each of these steps. Resist the temptation to leapfrog over a stage.

Stage 1. Denial: This first stage is not only about denying differences (“My cultural experience is the only one that is real and valid”). It is also about missing differences (“I don’t understand what all the fuss about differences is; there just aren’t that many differences among us”). When you are in denial, you don’t recognize that even visible differences (such as gender) might influence outlook, worldview, or perspective.

Denial is especially common in a very homogenous environment. When you rarely if ever have the opportunity to interact with someone with visible differences, you are not cued to think about the differences that lie beneath the surface. If you are in denial, your developmental task is to start to recognize that differences exist. (Note: If you are tempted to skip this step in the belief that you are not in denial, that’s a clue to explore your perceptions again!)

When one or both mentoring partners are in denial, there will be no true connection or understanding. Even if the mentoring partners identify as the same gender, race, educational background, or area of expertise, there will be nonvisible differences that make a difference. Perhaps these will be in learning styles, generations, values, or motivation, and certainly there will be differences in life experiences and expectations. But when someone is in the denial phase, they don’t notice any of these differences and so are connecting in a superficial, often transactional way.

Stage 2. Polarization: In the polarization stage you start to see differences, but you begin by preferentially critiquing and judging them. When you encounter a difference you evaluate that difference to determine whether it is “better” or “worse” than your own cultural preference. For example: “The way I do x is better than the way you do it.” “I prefer my orientation to the world to yours.” “I don’t like the way they look at this.” You end up spending time in your head processing the difference in order to judge it from your own cultural vantage point. When you are in polarization, your developmental task is to seek out commonalities.

FIGURE 8.1 Intercultural Development Continuum SOURCE: Bennett, “Intercultural

Communication: A Current Perspective.” © 2015–2017 IDI LLC used with permission.

If one or both mentoring partners is in polarization, they miss the chance for true connection because they are judging the difference rather than seeking to understand it. Curiosity is not present in polarization. Someone in polarization may wonder about another culture, but it is more voyeuristic than from a desire to understand.

Stage 3. Minimization: In the minimization stage you’re not necessarily judging the differences, but you are deemphasizing the differences from the perspective of your own cultural vantage point. For example: “I see the differences, but they don’t really make a difference.” “We are all fundamentally the same.” In some ways this is what so many of us were taught: minimize differences so that you can connect to the person. Yet if we do not acknowledge the differences between us, we cannot create true connection because we are not fully seeing or appreciating differing perspectives and experiences. If you deny an element of someone’s culture that is fundamental to their identity, saying “I don’t see you as x, I just see you as human,” the impact on the other person is to feel unseen. The statement “I don’t see you as a woman/African American/LGBTQ/etc.” is tantamount to “I don’t recognize who you are” and “I don’t care to understand how that element of your identity shapes who you are,” even if that isn’t what’s meant or intended.

Mentoring pairs in minimization are often blindsided by an issue or challenge that arises from difference. Because they are convinced that differences don’t make a difference, when a situation arises where they can’t relate to their mentoring partner, they become derailed. When one partner is in minimization, the other partner sometimes is covering or downplaying their own identity so as not to create controversy or conflict. The way we view respect differs by cultural orientation—the way we look at what is kind and nice, the way we look at what our ambitions are, the way we look at authority, the way we look at communication. How we see each other makes a difference. And recognizing that difference is the developmental task essential to getting to the next step: acceptance.

In the first three stages, we’ve moved along the continuum from not seeing difference (denial) to judging difference (polarization) to minimizing the difference (minimization). These are ethnocentric stages, meaning that when you see difference through your own vantage point, you evaluate other cultures according to the standards and customs of your own culture. In an ethnocentric stage you think about difference in terms of your culture. You might ask yourself, “How do people like me see this difference? How is this different than how I see myself?” Often, in an ethnocentric mindset we see difference as something that someone else possesses, rather than something that exists between people. To say that someone else is different makes your orientation normative and someone else’s deviant. Cultural competency is about understanding that differences exist between people and that there is no “normal” or “typical” or “right” when it comes to identity and culture.

Stage 4. Acceptance: When you transition into the fourth stage, acceptance, you move from an ethnocentric to an ethnorelative viewpoint. You stop evaluating and comparing and begin to approach difference by looking at things from other cultural perspectives. This was the “aha!” for Darren as he began to consider how Martin viewed his circumstance, just as it was for Heather when she began to understand that Aesha’s issues with work-life balance were coming from a much more culturally specific place than she had assumed. This fourth stage is a non evaluative phase. You see how things are viewed from other cultural perspectives. You get that differences make a difference. You understand that there’s an imperative for inclusion. You understand that the ability to make meaning depends on seeing that difference. Yet you don’t know how to walk the talk. You begin to ask yourself what to do about it. You have great intention and awareness, but you are not yet sure how to implement that intention.

When one mentoring partner is in acceptance, they often feel unable to add value to the mentoring relationship because, although they can see differences and often want to help bridge that difference, they lack the comfort or the skills to do so. We often find that mentors who are in acceptance seek out coaching or the advice of their peers to help them figure out the best way to guide their mentees.

Stage 5. Adaptation: The fifth stage, adaptation, brings us to what Milton Bennett calls “an intercultural mindset.” By this stage you are comfortable with many standards and customs, and can adapt your behavior to be culturally appropriate and culturally sensitive. Now you begin to implement the skill of bridging differences, of making that connection, of recognizing the difference, of recognizing where there might be a difference. If you find yourself at this end of the continuum, it does not mean that you know and understand the customs and ways of behaving in every single culture. When people talk about cultural competency, there are many differences you need to be aware of and questions you need to be asking so you can figure it out and relate across culture. If you locate yourself in adaptation, you know what questions to ask. You can operate in different cultures and recognize where people may approach differences.

In adaptation we understand where differences might occur, where our understanding may be incomplete, and what questions to ask to learn about differences. We act as a cultural liaison, helping others to see difference in a nonevaluative way, and as a cultural broker, who can be a go-between who advocates for someone of a different culture for the sake of reducing conflict or producing change.69 The mentor in adaptation can help their mentee better understand the organization and help the organization better understand the mentee. The mentee in adaptation can help the mentor better understand the mentee’s culture or peer group. Their developmental task in adaptation is to continue learning about different cultures and practice the skills of bridging difference to create a win for the mentor partner, mentoring relationship, and organization.

» YOUR TURN «

1. Note where you think you are on the continuum in Figure 8.1. What is your developmental task in order to progress to the next orientation?70

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. Note where your mentoring partner is on the continuum. If it is the same cultural orientation, what will you do together to develop along the continuum? If your mentoring partner has a different orientation, how will this impact your mentoring relationship?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. What can you and your mentoring partner do to develop your cultural competency?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Working with the Continuum

Let’s look again at Figure 8.1. How did Darren try to deepen his understanding about Martin’s situation and support him?

Looking at the continuum, Darren would likely place himself in acceptance at the start of his mentoring relationship, moving to adaptation sometime during the year. As an African American man working in corporate America, Darren has been conscious of differences for as far back as he can remember. He didn’t want to project his experience with differences onto Martin though, so he made sure to ask questions and acknowledge that Martin’s experiences and cultural reference points were different than his.

Darren didn’t get too hung up on whether it was his age difference, years of experience, or racial or ethnic identity that were the source of their differences—he just wanted to understand Martin. So, as he listened, he asked a lot of questions. Where it was appropriate, he shared his own stories with Martin, and together they discussed ways that Martin could discover his own strengths and show up authentically. Through these conversations, Darren became more conscious about ABC’s policies and practices and how its managers were developing their teams. He started to notice little and big improvements he could implement to improve communication and make the workplace more inclusive.

With Martin’s permission, but without mentioning Martin, Darren spoke with Charla, his colleague who oversaw manufacturing and sat on the senior leadership team. Darren had been eager to follow up and find out how manufacturing leadership evaluated performance and what criteria they used. After his conversation with Charla, he felt much better equipped to help Martin understand and navigate ABC’s organizational culture and avoid obstacles. Darren and Martin talked about ways Martin could advocate for himself effectively within ABC and still show up as himself.

Martin was grateful for Darren’s interest and expertise, and he put his newfound knowledge to use right away. Nonetheless, he soon found himself stuck on a new plateau.

Working on the PIE: Performance, Image, Exposure

During one mentoring meeting, Martin lamented to Darren: “My performance is great. I always meet my metrics. Why aren’t I getting anywhere?”

Darren could absolutely relate. He remembered the advice his favorite high school teacher gave him: “Be so good they can’t ignore you.” Darren knew that performance was only a small piece of the equation, and that the secret to discovering why Martin felt so stuck was in how he was viewed and his exposure to opportunities and even how he viewed himself.

According to Harvey Coleman, author of Empowering Yourself: The Organizational Game Revealed, three factors contribute to success in the workplace: performance, image, and exposure (the PIE model). “Performance” is the quality of your work. “Image” is how you are perceived. “Exposure” is about visibility—access to opportunities, to a network, and to people who can advocate for you.71 In a perfect world, we would be judged 100 percent on performance. However, Coleman’s model suggests that performance accounts for only 10 percent of success while 90 percent of an individual’s success is due primarily to a combination of image (30 percent) and exposure (60 percent).

It is true that doing a good job is table stakes for success. Without satisfactory performance, we will not get very far. However, the PIE model reminds us that performance will not get you all the way there; in fact, it won’t even get you close. We must pay attention to our image, which is influenced by how we show up and by how we are perceived. For mentees, this means looking at how we are presenting ourselves and how that might be perceived. For mentors, this means providing feedback on how mentees are perceived, providing coaching on how to show up authentically and navigate organizational dynamics and customs. For mentors and organizations, this means noticing, managing, and advocating for change in areas where there is conscious or unconscious bias that is unfairly or inequitably working against the mentee.

We must also attend to exposure. Mentoring can make the biggest difference in this area. Mentors can open up their network to their mentee; offer perspective about additional opportunities for work experience or networking; and, with their mentee’s permission, advocate for their mentee in situations where the mentee might not otherwise have exposure or access. How did Darren use the PIE model in his mentoring relationship with Martin?

As Darren reflected on the PIE model, he thought of his own privilege. He realized that his long tenure in the organization—more than thirty years—had helped contribute to how his performance was viewed and that had been his ladder to success. Because he had been there such a long time, and because he was in a leadership role, he had a presumed sense of credibility when he spoke. It hadn’t been easy, and as an African American man, Darren still did not have the presumed sense of belonging many of his white colleagues had. There were a lot of years early on when Darren was passed over for opportunities, and many meetings to which his white colleagues were invited from which he was excluded. His own mentor had helped him build relationships at ABC. Darren had worked hard to build his network and to nurture it, and over time it had paid off. He had hoped he could now work with Martin to pay it forward a bit.

For his part, Martin realized it wasn’t his performance that was holding him back. It was his lack of access to networks. It was his lack of social capital. It was the way he was perceived. He now believed that his colleagues did not understand his cultural differences. They misinterpreted his style of asking questions and his inquisitiveness. Because Martin held the view that if his team didn’t rise, he didn’t rise, he now realized that he had spent most of his time advocating for his team and not enough time advocating for himself.

Darren was able to help transform Martin’s thinking and acting by understanding that there were other critical components that needed to be addressed in order to help Martin succeed. Darren’s task was to support Martin by helping him gain exposure and become more aware of his image. Ultimately, because of Darren’s position, he was able to influence the organization to become more conscious of how it viewed employees who are traditionally marginalized or underrepresented or who have a nontraditional path.

Here’s the lesson of the PIE model: Instead of working together to create a goal that helps an employee do their job better, effective mentoring partners focus their time working on goals that require the mentee to enhance their image or exposure. Is there a particular skill, behavior, or competency they might work on (image)? Can they become more aware of how they are perceived by others (image)? Are there people whom they should meet to expand their network (exposure)? Are there development or job opportunities they might not be aware of (exposure)? Is there a body of work or area of expertise with which they are unfamiliar that might be helpful (exposure)? Framing goals to increase image and exposure is more likely to take into account individual differences and result in more motivation and momentum to the mentoring effort.

Enabling Growth through Support, Vision, and Challenge

How does a mentor help a mentee expand their image and exposure? The mentor’s work falls into three facilitation categories. The mentor supports the mentee by nurturing and establishing a mentoring relationship that promotes learning and development. The mentor assists the mentee in creating and articulating a vision, and moving toward realization of their vision. The mentor challenges and motivates the mentee to stretch and gain traction toward achievement of goals. Each of these must build upon their trust and awareness and must leverage the learnings about their mentoring partner to enable meaningful growth.

The mentee’s responsibility during this time is to communicate their needs to their mentor. It moves things along if a mentee has thought about what type of support helps them in their learning and what kinds of support they would like to receive from a mentor. What is helpful? What is not? Envisioning a realistic future is often difficult. When it comes to a possible future, most mentees don’t know what they don’t know. The best advice we give the mentees we work with is to maintain an open mind and communicate openly. When mentees let their mentors know how they like to be challenged, and what’s missing from any current mentoring relationship, it can only help their mentor know where, when, and how to offer guidance to them.

Support

For support to be meaningful, it must be the right kind and provided at the right time. This is a formidable task. Mentors need to “get” their mentees, to understand who they really are. Only when mentees bring their authentic selves to mentoring can a mentor bring timely and relevant support for the relationship and learning. This means that mentees need to remain open to learning and be comfortable being themselves (vulnerabilities and all). How did things evolve for Martin as he worked on the guidance Darren provided?

Finally, after six months, things started to improve for Martin. As he continued to work on his Performance Improvement Plan (PIP), he held several conversations with his manager and now felt more optimistic that the expectations his manager had laid out for him were realistic and doable. Once Martin bought in, he was excited to be working more on his own development.

Darren exercised his curiosity. He needed to gather more information before he felt he was in a better position to help Martin realize that Martin was the only one who could change his own circumstances. Finally, Darren and Martin reached a point where they both felt the shift in Martin’s outlook and progress. Martin was also getting increasingly curious—the more he learned, the more he wanted to know. Each became more curious about the other. They decided to hasten the process by starting their meetings with a power question that would help them get to know each other even better.

When the mentoring program administrator called Darren to see how things were going, Darren reported, “I am getting to know how he ticks, and I’m learning so much from him about the manufacturing world and what more we can be doing as a company. I am also learning about the thinking of the younger demographic that he represents.”

Darren had come to believe that authority and power didn’t hold the same value for Martin’s generation as it did for his. Like many of his age contemporaries, Martin believed he could and should take on significant responsibility and make a major contribution as quickly as possible. He brought fresh perspectives and could see how they could make a difference. As a mentor, Darren’s big “aha” was that he needed to acknowledge what Martin brought to the table, and the only way he could do that was by asking questions to discover who Martin was and the talent he possessed. Darren expressed positive expectations about Martin, not only by showing he was actively listening but also by encouraging him to create a more effective structure for completing his PIP in a more timely fashion.

Things were going along smoothly, and Martin was feeling more energized and optimistic. But then his father passed away unexpectedly, and the shock stopped Martin in his tracks. He had been very close with his father, and he was devastated by the sudden loss. Although he returned to work a week after the funeral, he wasn’t the same Martin, not for months. Darren wondered how he could best support Martin during this time. He chose to let Martin lead the way, and they spent a few months of their mentoring time talking about how Martin was coping with his loss.

Darren asked Martin questions about what rituals his family had to mark a loved one’s death. He listened as Martin told him about novenas, the prayers that were said during the nine days after his father’s death. Martin believed these prayers would protect his father after his death; he was glad that he was able to pray and grieve openly with his family during this time. Martin shared that, in his family’s tradition, openly displaying emotions about grief was expected and encouraged.

Sometimes Darren would share his own family’s traditions and his experience when his father had died a few years earlier. At each meeting, Darren would ask if Martin was ready to shift to talk about his mentoring goals; each time, Martin would ask to wait just a little bit longer.

Darren wanted to be respectful but also did not want Martin to lose the momentum they had started to build before Martin’s father’s passing. Darren suggested that they revisit the agreements they had negotiated six months earlier. Instead of meeting every two weeks, they mutually agreed that a short time-out was in order. They agreed to touch base in a month, and they both set a reminder on their calendars.

Vision

When it comes to creating, articulating, and initiating a vision, it is important that mentors have a deep-seated understanding of who their mentee is, where they are in their career trajectory, and what they hold to be meaningful. A mentee will never realize a vision to which they do not feel connected. How did Darren and Martin find their vision?

About six weeks later (nine months after they had started their mentoring relationship), Darren and Martin began to meet again. Martin was feeling better and, to his great relief, was back on track. He had successfully completed his PIP. He was still in manufacturing, but as a result of the work that he and Darren had been engaged in together, Martin discovered he had a real knack and enthusiasm for process improvement, which required motivating others and improving the way things got done.

Darren and Martin worked on Martin’s communication and influencing skills so that he would be ready when a role in process improvement opened up. Martin’s perspective shifted. He realized that he could add value by developing in place and positioning himself for a new role when it became available. “I have so far to go, but I realize that my success is on me.”

Darren wanted Martin to get a sense of what was possible, and he introduced Martin to some colleagues who had different backgrounds, perspectives, and job functions. This shook Martin out of his fixed mindset. His perspective expanded with new possibilities, and he felt less isolated. He began to formulate a vision for himself. He realized that he needed to build broader relationships so he could move out of manufacturing and get a better handle on the skills he needed to develop to realize his vision. He immediately followed up on Darren’s introductions and made appointments with each of the people Darren suggested he meet.

Martin began to see Darren not only as his mentor but as a colleague and one of many resources available to him. One day he turned to Darren and said, “I now know what it takes, and I am ready for the challenge.”

By expanding Martin’s awareness of what might be possible, Darren had helped Martin set a vision for himself that he could get excited about. Notice that Darren did not map out a plan for Martin. Instead, they talked about what Martin might be interested in, and Darren increased Martin’s exposure so that Martin could see other options for himself.

For Aesha and Heather, our mentoring pair from earlier in the book, the concept of vision played out in their story in different ways.

Heather saw that Aesha understood the workings of the organization. She collaborated well with others and already possessed a set of technical skills that brought her continued recognition. However, Heather was not sure that Aesha understood the “why” of health care, and she thought it would serve Aesha well to do so. Aesha’s work supported those who care for patients, although she was not a direct patient caregiver. Heather realized it might be helpful for Aesha to understand consumer relationship management. Heather didn’t feel up-to-speed on all of these aspects, so she suggested that Aesha might want to interview three people who understood these aspects well. That way, she could learn along with Aesha.

Aesha was all for conducting informational interviews with seasoned health-care individuals who might help her understand consumer health-care marketing, the financing of health care that impacts consumer choice, and the upstream/downstream impacts of a single health-care encounter. She realized that she had never really given thought to the people who health care affected. She asked Heather for names of people to contact. Together they made a plan for Aesha to conduct informational interviews and report back on what she learned. Aesha was excited about the opportunity and very pleased with the list of questions she and Heather had generated to guide the interviews.

In both these examples, reaching beyond the known enabled mentees (and their mentors) to enhance their networks and to gain and shift perspectives.

Challenge

Challenge is the third condition that promotes learning during the enabling growth phase. This is when tasks are set. The mentor challenges and stretches the mentee’s thinking and sets high standards for reaching the goals. If you are a mentee, your role during this time is to remain open to possibility, to challenge yourself to do things you haven’t done before, to take risks and be willing to explore new ways of thinking. Asking questions, even when you think you know the answer, often reveals interesting surprises. As a mentee, it is vitally important to learn to understand what you need and to ask for it. Challenge is not only a time for the mentor to challenge you, but for you to challenge yourself.

Consider discussing the importance of challenge with your mentoring partner. It can be helpful to explicitly give each other permission to explore your differences, which sometimes may result in what feel like difficult conversations. Understand that you will make mistakes and know that when challenge arises, it comes from an intention to understand one another. This will allow you to give each other grace.

Challenge looks different depending on your cultural view of autonomy and authority. Someone with a strong orientation toward authority, for example, may be more inclined to seek and follow specific directions from their mentor. They might seek frequent check-ins to ensure they are accountable and on track. Someone with a strong orientation toward autonomy, however, may find specific direction stifling or intrusive. Accountability will still be useful, but it could be more informal. In either case, mentors and mentees will not know what works until they ask. Helpful questions may be “How shall we check in with one another?” and “What level of detail will be helpful to you?”

Another element of challenge is for the mentor to gently push the mentee out of their comfort zone to try new things. Is there a presentation they can craft? Is there a white paper they can create or a process improvement they can suggest? Is there a new procedure or policy they might recommend? Are there people they should be networking with whom they haven’t mustered the courage to approach? Again, mentees will vary in their willingness to stretch. It can be helpful to create space in mentoring meetings for a mentee to “test drive” the challenges they take on. If you both have created a safe space for sharing, your mentoring relationship will also likely be a safe space to experiment. Use your mentoring time to role play, practice a presentation, review and give feedback on a first draft, and so on. Find a zone of comfort that works for both of you. The beauty of the mentoring relationship is that it provides a safe place to take risks and experiment with new possibilities. It becomes easier to accept the mentor’s challenge when the mentee can take a test run and practice the new behavior. (Chapter 9 on feedback offers some suggestions on constructive ways to use the “test drive” time.)

Let’s look at Aesha and Heather’s use of time during their meetings.

Aesha and Heather spent one of their meetings role playing the informational interview session that they had agreed on as a goal for Aesha to learn more about the health-care industry. Heather had promised to make the most of that time, so rather than just offer a “Good job!” during the role play, she played the role of an unwilling interviewee.

Heather was impressed at how well Aesha was able to handle the situation. She was especially struck by Aesha’s ability to ask questions in a way that would help Aesha turn these informational interviews into valuable networking opportunities and connections down the line. Heather thought these learning experiences would also help Aesha in her current role.

» YOUR TURN «

(for Mentors)

1. What are specific examples of things you would do or say to support a mentee?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. What are specific examples of ways you could help a mentee see, develop, and realize a vision of their future?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. What are some specific examples of how you might challenge a mentee?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

» YOUR TURN «

(for Mentees)

1. What do you need from a mentor to feel supported?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. What do you want your mentor to say or do to help you see, develop, and realize a vision of your future?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

3. When you experience a learning challenge, what helps you tackle it?

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

In the next chapter we look at some of the problems that mentors and mentees may discover as they try to bridge differences. We explore the importance of providing meaningful and culturally respectful feedback and offer a framework for doing that. Finally, we delve into the nature of mutual accountability.

Chapter Recap

1. One key to understanding your mentoring partner is to determine what lies at the intersection of what they are excited about and what they are good at. This is called native genius.

2. Cultural competency is how we make sense of difference. By recognizing and approaching difference with a sense of curiosity rather than judgment, we can effectively learn from and leverage difference. This is the adaptation phase on the Intercultural Development Continuum (see Figure 8.1). This continuum provides a helpful developmental model for cultural competency.

3. Most career success depends on how we are viewed in the workplace and our exposure to people, opportunities, and resources. Though excellence in job performance is important, it is only a small factor in overall success, and performance goals can be addressed by the mentee’s supervisor. Learning in mentoring should focus on improving image and increasing exposure—the two factors that will contribute to most of the mentee’s success.

4. Mentees look to mentors to provide support, challenge them, and help them set a vision for success. It is essential to have a discussion with your mentoring partner about what support, vision, and challenge look like for each of you.