If you’ve used an operating environment other than Mac OS X (such as Windows or Unix), you’ve probably had to worry about environment variables and configuration files. Such nuisances are pointedly missing from most Mac OS X applications, because Mac OS X uses a database to store all such configuration and user-preferences information. This database is called the defaults database .

The Mac OS X defaults database stores the preferences set in the Preferences dialogs of all applications. As a Cocoa programmer, you can use the defaults database system to store whatever information you want.

The Mac OS X defaults database is similar to the registry in Microsoft Windows, but with one critical difference — Mac OS X applications use this database only for storing preferences, not for storing critical information that is necessary for the proper operation of an application. Unlike Windows, where registry keys must be created when an application is installed, Mac OS X applications create their defaults entries when they run — and they automatically recreate the settings if they are accidentally or intentionally removed. Furthermore, the settings in the defaults system never contain full application pathnames — applications find where they are installed by examining their MainBundles (the directory from which the application is run). Thus, you can move an application and it will still work properly.

In this chapter, we’ll modify the GraphPaper program to work with the defaults database system. We’ll use the database to store the colors used to draw the graph, axes, and labels. In the second half of this chapter, we’ll use the defaults system to store the initial values for the graph parameters. Finally, we’ll create a multi-view Info dialog to switch between these two preferences options.

Mac OS X

stores preferences information for each application in a file located

in the user’s

~/Library/Preferences/ folder. The preferences

files are actually XML-encoded property lists with the

.plist extension. To prevent namespace

collisions, each file is named using the reversed fully-qualified

hostname of the company that created the application (e.g.,

“com.apple”), followed by the

application name (e.g., “clock”).

Apple calls these names

domains

.

Defaults domains are similar in appearance and spirit to class names

in the Java programming language. For example, the Clock application

stores its preferences information in a file called

com.apple.clock.plist.

Because the ~/Library/Preferences folder is

stored under the user’s Home folder, each user has

her own preferences information. If you NFS-mount a

user’s Home directory in a networked environment,

that user will have access to her preferences information regardless

of which computer she uses for login.

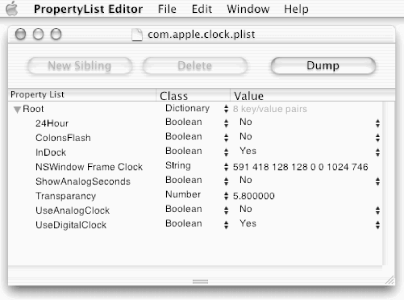

If

you double-click

~/Library/Preferences/com.apple.clock.plist in

the Finder, the PropertyListEditor application will open and display

a window similar to that in Figure 21-1 (click the

disclosure triangle next to Root, if necessary).

You can edit a .plist

file in PropertyListEditor using the

steppers and New Sibling and New Child buttons (recall that we did

this earlier in PB). Try changing the InDock property of the Clock

from Yes to No (or vice versa) using the stepper at the far right of

the window, and then save the

com.apple.clock.plist file. If the Clock is

already running, it won’t change its Dock status

immediately. However, if you quit the Clock application and then

restart it, it should change its Dock status. Changing

preferences

of a running application in PropertyListEditor is dangerous, because

the running application may also change the preferences, which can

lead to inconsistent results. It’s like two people

editing the same exact file on a server and saving it at different

times.

When we clicked the Dump button in the upper-right corner of the

PropertyListEditor window, we got the window containing the ASCII

dump of the com.apple.clock.plist file, as shown

in Figure 21-2.

When we listed the exact same

com.apple.clock.plist file in a Terminal shell,

we got the same listing as in the PropertyListEditor dump:

%cd ~/Library/Preferences/%cat com.apple.clock.plist<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <!DOCTYPE plist SYSTEM "file://localhost/System/Library/DTDs/ PropertyList.dtd"> <plist version="0.9"> <dict> <key>24Hour</key> <false/> <key>ColonsFlash</key> <false/> <key>InDock</key> <true/> <key>NSWindow Frame Clock</key> <string>591 418 128 128 0 0 1024 746 </string> <key>ShowAnalogSeconds</key> <false/> <key>Transparancy</key> <real>5.800000e+00</real> <key>UseAnalogClock</key> <false/> <key>UseDigitalClock</key> <true/> </dict> </plist> %

Only printable ASCII text should be stored in the database, but Apple’s XML encoding system should take care of this for you automatically.

In addition to

PropertyListEditor,

Mac OS X provides a Unix command-line program called

defaults

for reading and modifying the contents

of the defaults database.

The defaults command makes it possible to use and

modify the defaults database without having to start up a Mac OS X

program and read the XML property list. That’s handy

if you’re writing a shell script or just trying to

learn your way around the defaults system. The

defaults command can also read the contents of the

defaults databases on other computers, provided you have sufficient

permissions to do so.

The primary functions of the defaults command are

summarized in Table 21-1.

Table 21-1. Defaults system commands

We can use the defaults

read

command in a Terminal window to see all of the

variables and defaults for the Clock application:

%cd ~/Library/Preferences/%defaults read com.apple.MenuBarClock{ AppendAMPM = 1; ClockDigital = 1; ClockEnabled = 1; DisplaySeconds = 1; FlashSeparators = 0; PreferencesVersion = 1; ShowDay = 1; } %

If we wanted to make the clock’s AM/PM indicator disappear, we could execute this command:

% defaults write com.apple.MenuBarClock AppendAMPM 0

%That wasn’t terribly informative. What’s worse, if you execute this command and then look at your clock, you’ll see that the AM/PM indicator is still there. Did the command take?

% defaults read com.apple.MenuBarClock

{

AppendAMPM = 0;

ClockDigital = 1;

ClockEnabled = 1;

DisplaySeconds = 1;

FlashSeparators = 0;

PreferencesVersion = 1;

ShowDay = 1;

}It looks as if the command worked, but its effects

haven’t shown up yet. Try clicking the menu bar

clock and then choose View → as Icon. Click the menu

bar clock once again and choose View → as Text. Now

the AM/PM indicator should disappear. The behavior of preferences in

other applications may differ — it depends on how often the

program checks the defaults database stored in its

.plist file.

The Mac OS X defaults system is designed to accommodate multiple defaults domains. Each domain is a collection of names and values. Internally, Cocoa implements defaults domains as NSDictionary objects that store zero or more other objects. The key to the NSDictionary is the name of each defaults value; it is determined by an NSString object. The value can be any object that can be stored in a property list — that is, an NSData, NSString, NSNumber, NSDate, or NSArray object, or another NSDictionary object.

Every application that you run can have its own defaults domain. The name of this domain is the same as the application’s application identifier, which is set in Project Builder.

Defaults domains can be persistent or volatile. A persistent domain is a domain that is stored after an application exits and is made available again the next time that application runs. The contents of a volatile domain are simply lost when the application finishes executing — but that doesn’t matter, because they are recreated the next time the application runs.

Persistent defaults domains are typically stored as files in the

user’s ~/Library/Preferences

folder, but they could in theory be stored in other locations, such

as in a SQL database or an LDAP server. In fact, the mechanics of how

persistent defaults are stored and then loaded back into memory are

intentionally hidden from the programmer.

Mac OS X provides each application with five standard defaults domains, described in Table 21-2.

Table 21-2. Defaults domains available to every application

|

Domain |

Purpose |

Type |

|---|---|---|

|

NSArgumentDomain |

Stores the command-line arguments provided when the program is run. |

Volatile |

|

Application[a] |

Provides persistent storage of the user’s preferences and other values. |

Persistent |

|

NSGlobalDomain |

Used by user-interface objects that require a consistent behavior between user applications. |

Persistent |

|

Languages[b] |

Used for language-specific default values. For example, NSGregorianCalendarDate, NSDate, NSTimeZone, NSString, and NSScanner use this defaults domain to remember language-specific defaults (such as the names of the days of the week). |

Volatile |

|

NSRegistrationDomain |

Stores application-specific defaults of applications before they are changed by the user. |

Volatile |

[a] The name of this domain is the same as the name of the application identifier. [b] The names of these domains correspond to the name of the language. | ||

The NSUserDefaults class is the standard interface that you will use to communicate with the defaults system. Your application will create a single instance of this class; you can get the id of this instance using the class method +standardUserDefaults . For example:

NSUserDefaults *defaults = [NSUserDefaults standardUserDefaults];The NSUserDefaults object implements a search system by which successive domains are searched when you ask to look up an object by key. The domains are searched in the order given in Table 21-2:

The NSUserDefaults object first checks the NSArgumentDomain, which is built from the command line that was used to launch the application, if one exists. This lets you temporarily change the value of a preference for a single run of an application.

If no command-line value was given, it next checks the application domain, as specified by the application’s bundle identifier.

If no owner/name combination is found in the defaults database, the NSUserDefaults object next checks for a default in the NSGlobalDomain.

If no NSGlobalDomain default is found, the NSUserDefaults object checks the domains for each of the user’s preferred languages.

If no default has been found up to this point, the NSUserDefaults object returns the value that was specified in the registration table that was registered in the NSRegistrationDomain.

This search order of the application’s compiled-in defaults will be honored unless they are superseded by defaults specific to the user’s language, defaults that have been stored, or command-line arguments.

If we want the GraphPaper application to start up with an

xstep of 5, we could launch it with the following

command line in the Terminal:

% build/GraphPaper.app/Contents/MacOS/GraphPaper -xstep 5When your application starts up, it needs to read the

user’s default values and set the state of its

associated objects. Recall that in Chapter 17 we

simply hardcoded values to use for defaults in

ColorGraphView.m and in Interface Builder.

We’ll change that in the next section.

The most obvious use of the defaults system is to remember user preferences between successive invocations of an application, but the defaults system is actually used throughout the Mac OS X environment. For example, Cocoa’s NSRulerView class references the NSGlobalDomain to remember if the user’s preferred unit of measurement is picas, points, inches, or centimeters. The internationalization of Cocoa is provided through the AppleLanguages key that is stored in the NSGlobalDomain defaults domain, which allows users to specify which languages they want to use, and in which order.