Chapter 7

Who motivates the motivator?

‘Everyone has been made for some particular work, and the desire for that work has been put in every heart.'

Rumi

The first thing to understand about motivation is that its origins lie deep in our psyche but are also influenced by environmental factors. Motivation is multifaceted and individualistic.

Most leaders know they need to provide a cohesive and inspiring work environment, but is that enough? Much has been said about workplace engagement in recent years, but employers cannot and should not attempt to own an employee's engagement. For one thing, many factors external to the workplace affect employee engagement. As discussed in chapter 1, ‘employee experience' is now considered a critical factor that coexists with employee engagement rather than replacing it. That said, the basic building blocks of career satisfaction, motivation and engagement come from the employer providing a workplace culture and physical environment compatible with the values and personal desires of the employees.

Models of human motivation — what works best

There are hundreds of models that attempt to define and explain human motivation, and most have some validity. For our purposes, though, I have highlighted the three that I believe are most useful in the context of career conversations. These are:

- Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs

- Daniel Pink's theory of intrinsic motivation

- Max Landsberg's skill/will matrix.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs

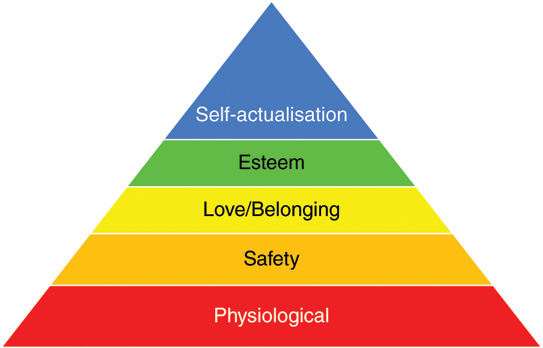

First proposed in 1943, Abraham Maslow's hierarchy identified five stages of human needs that culminate in self-actualisation (see figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1: Maslow's hierarchy of needs

- Physiological needs include food, water, shelter, warmth and sleep.

- Safety needs include financial security, personal safety and social stability.

- Love/belonging needs include affiliation, friendship, relationships and intimacy.

- Esteem needs include self-respect, status, prestige, accomplishment and recognition.

- Self-actualisation needs relate to personal growth and achieving one's potential.

According to Maslow, each level of needs, beginning with the basic physiological, must be satisfied before the next level can be achieved. Although conceived many years ago, this model remains relevant to any consideration of motivation, whether in a personal or a career context. For instance, it's hard to be concerned about career development if your employees can't afford to put food on the table or are fearful, overwhelmingly anxious or depressed.

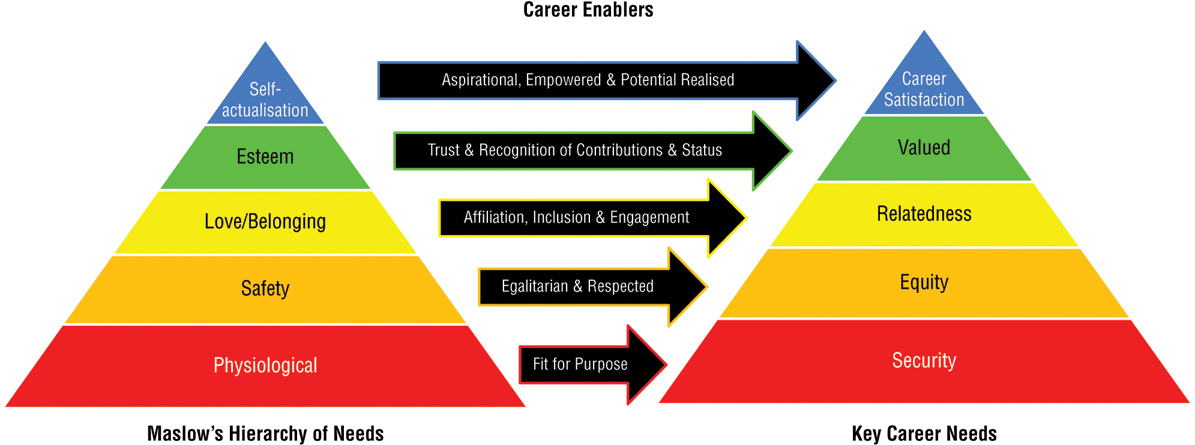

Revisiting Maslow in 2016 in the context of leadership and employee engagement, Shea Heaver mapped the ‘5 mindsets that individual employees (and by association their teams) can be encouraged to strive for within the workplace'. This inspired me to consider how useful Maslow's model could be for leaders in a career context as well.

For this purpose, in figure 7.2 (overleaf) I have adapted Heaver's concept and diagram to apply Maslow's hierarchy to key career dimensions, along with their enablers.

Figure 7.2: a hierarchy of needs for career development (after Maslow)

Let's now look a little closer at each career need and enabler and their relationship to Maslow's model.

Meeting security needs (physiological) is about having a fit for purpose work environment and employment relationships. It's no longer about jobs for life! Leaders need to make sure they are listening and acting decisively in relation to their employees' pain points. One of the key employee criticisms of engagement surveys is that management fails to act on their feedback. In my experience, the only thing worse than not seeking employee feedback is failing to deal swiftly with the employee pain points it reveals. This is dynamite for leaders, but paradoxically it's often where you can get big wins from making only small changes to the operating environment.

The security needs level is the base level in the workplace. It's where leaders build trust and confidence in their employees. Career conversations help build these positive and solid foundations. The two operative words for leaders are listen and act!

Fulfilling equity needs (safety) is fundamental to the health of employee relationships and relates directly to the quality and scale of their contributions and motivation to innovate. Employees do not perform to their potential, nor are they motivated to innovate, if they feel marginalised and that their input isn't valued or, worse, that their contributions will be mocked. Research shows that employees respond positively to progressive, transparent and open work cultures where they can put forward their views without fear of ridicule in a safe environment.

On the flip side, over-controlling managers stifle innovation and discretionary effort by criticising and punishing employees who challenge the status quo — specifically, them! Leaders must be open and ready to recognise and reward employees who demonstrate new ways of thinking and who look outside the square for new ideas in an increasingly dynamic world. Put simply, leaders must create a culture that fosters and nurtures openness and acceptance of new ideas. If we all sit around and just agree with each other, nothing ever happens! A safe environment makes it easier for leaders to challenge their employees' career goals when appropriate and in turn relish feedback on their own leadership performance.

Satisfying relatedness needs (love and belonging) builds on the equity level by developing diversity and collaboration comprehensively throughout the organisation. Achieving unity of purpose while fostering diversity can challenge the most experienced leader. For this reason it's critical for leaders to have a very clear, well-articulated vision of the future, but at the same time to retain flexibility in how their vision can be achieved.

Inclusion is the key to driving simultaneously diverse thought, constructive conflict and productive collaboration. Inclusion is a basic social need; when not reciprocated, it can cause one party to withdraw from the relationship and turn their attention inward towards self and away from colleagues and the organisation. When inclusion is engaged positively — when differing points of view are valued, and openness, respectful communication and acceptance of others are fostered — proactive feedback has the potential to improve work outcomes and practices.

Leaders have a significant role to play in creating and nurturing a culture of inclusion to ensure all employees feel they can influence organisational outcomes. Leaders should have the courage to ‘take the speed brakes off' their employees and organisation to allow free-flowing innovation and collaboration, confident that such a culture of openness and trust will enhance employee engagement and experience.

Value needs (esteem) are a game changer that can lead to organisational functioning of a high order. Building individual and organisational trust is a fundamental leadership responsibility and skill. As discussed in chapter 1, trust is the great enabler of learning and career development. The foundation of effective collaboration is critical to continuous improvement and high performance and is a potent force for self-esteem. Self-esteem is enhanced by a culture of openness in which employees feel valued by their leader and colleagues. Just as self-esteem is closely connected to self-awareness and self-determination, both of which are essential to individual career development (and leadership), leaders who value insight and mutual understanding and develop collaborative organisational systems build highly progressive and successful work cultures.

In my experience, leaders who help employees build their self-esteem see this reflected in their employees' career development and success. This, however, depends on the extent to which employees let you, as their leader, into their world, which in turn depends on the mutual trust in your relationship. This can be kick-started by the leader who is the first to ‘open up' and expose their own vulnerabilities. Try it — I'm sure you'll be rewarded!

Career satisfaction needs (self-actualisation) sit at the top of the pyramid, the target for all those with achievable life and career goals who seek empowerment, decision autonomy and the prestige of leading and inspiring others. At this level employees strive to better themselves and those around them for the greater good, in the long and short terms, where satisfaction is a tangible outcome. Authentic leaders who are great influencers and coaches thrive at this level by plying their craft with skill and unswerving commitment. These highly capable leaders inspire innovation and drive in their employees and protégés, motivating them to realise their full potential.

Recognising these levels of career needs and their corresponding enablers provides leaders with an opportunity to encourage the behaviours and mindsets required to enhance their leadership effectiveness and build an environment of mutual commitment. Having the opportunity and privilege to help an employee achieve and engage at this level is one of the most rewarding and exhilarating experiences you're likely to have as a leader!

Intrinsic motivation theory

An understanding of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation can provide leaders with valuable insights when in conversation with employees about their careers, or anything else for that matter!

In his book Drive, Daniel Pink contrasts intrinsic motivation, which relates to actions and behaviours prompted by the sheer enjoyment the activity brings you, with extrinsic motivation, the focus of which is external reward and punishment mechanisms.

For example, you might pursue a goal that holds a special personal meaning for you or that means your efforts or achievements are recognised by others (intrinsic motivation). Or you might pursue a certain course specifically for its monetary or other tangible reward (extrinsic motivation).

Pink contends that intrinsic motivation outlasts extrinsic motivation and drives superior performance. ‘Intrinsically motivated people usually achieve more than their reward-seeking counterparts.' He points out that this does not always apply, though. ‘An intense focus on extrinsic rewards can indeed deliver fast results. The trouble is, this approach is difficult to sustain.'

Intrinsic behaviours, Pink suggests, have three key ‘nutrients'. These are:

- autonomy — valuing self-determination and engagement over compliance

- mastery — improving professional development and skills to create a sense of achievement and progress

- purpose — pursuing goals that satisfy an intrinsic sense of meaning and purpose (for example, to ‘make a difference' rather than just to earn a living).

‘According to a raft of studies from SDT [Self Directed Theory] researchers,' says Pink, ‘people oriented toward autonomy and intrinsic motivation have higher self-esteem, better interpersonal relationships, and greater general well-being than those who are extrinsically motivated.' Pink's view of intrinsic factors as primary drivers of sustained motivation accords with my own experience that as a leader you cannot meaningfully or sustainably motivate anyone, because motivation must come from within your employees rather than external sources.

The skill/will matrix — useful ways to lead and coach

Max Landsberg popularised the skill/will matrix in his book The Tao of Coaching (1997), drawing on an adaption by Keilty, Goldsmith and Co, Inc. of original work by Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard. Hersey and Blanchard are best known for their work on situational leadership in the 1970s and 1980s.

This model provides a really useful heuristic to assess the relative contribution of an employee's ‘skill' and ‘will'. Leaders can use this model as a diagnostic tool for managing, coaching and developing their employees with the objective of moving them towards the High Skill / High Will quadrant (see figure 7.3, overleaf).

Figure 7.3: the skill/will matrix

Source: M. Landsberg (1997), The Tao of Coaching, Knowledge Exchange, LLC, Santa Monica, CA.

The brilliance of this model lies in its simplicity. It is intuitive and in my experience a very reliable leadership and development tool. Following are some leadership tips to manage and develop employees for all four quadrants of the matrix.

Direct (low skill / low will)

- Check possible reasons for low ‘skill' and ‘will'.

- Identify motivations.

- Build skill and will.

- Foster/celebrate small steps and maintain the will.

- Provide frequent feedback and monitor closely.

- Train and coach.

Guide (low skill / high will)

- Provide training and coaching.

- Be responsive to questions and clear with explanations.

- Foster a fear-free environment that provides opportunities for your employee to take risks and make mistakes to facilitate personal learning and development.

- Provide feedback.

Excite (high skill / low will)

- Check possible reasons for low will.

- Help them to understand what motivates them.

- Encourage a solutions focus (see chapter 9).

- Provide feedback, acknowledge success.

- Monitor your employee.

Delegate (high skill / high will)

- Provide discretion to self-direct and perform.

- Praise and acknowledge success.

- Seek opportunities to further stretch your employee's capabilities (e.g. higher duties).

- Coach and avoid close management.

The skill/will matrix is a great tool for career conversations and development. It can help you shape unique career discussions based on where your employee sits on the matrix at any given time, their progress and what approach might work best for that individual. A subpar performance by a highly capable and experienced employee could be the result of a combination of factors relating to personal, role, employer or career dissatisfaction (high skill / low will).

You can help them uncover their motivations and move forward by asking solution-focused questions, listening intently and encouraging a solution-focused conversation. For example, ask, ‘Tell me about a time in your career when you were highly motivated and deliriously happy. What was going on and what were you doing?' Focus on their answer and ask for detail about what made them happy. This might include finding out about anyone who has been instrumental in helping them along the way (and their attributes).

Guiding your employees towards uncovering previously unrecognised patterns and resources that have played a part in their success is a powerful tool for determining what has worked and might help them in the future. This may provide valuable insights into their satisfiers and dissatisfiers and their low will. See chapter 9 for more on the practice and benefits of a solution-focused approach.

Sonia's career story

Sonia, an events coordinator, was unhappy in her role and shared this with her manager, Jackie, during a routine weekly catch-up meeting. Sonia and Jackie had a solid relationship built on mutual trust. Sonia's revelation didn't surprise Jackie, who had noticed how her energy had dropped considerably and quite suddenly in recent weeks. Her efforts to uncover what was wrong, however, failed to shed any light on what had changed for Sonia, either professionally or personally. As the meeting progressed she sensed Sonia's growing frustration. After some deep listening on Jackie's part, and some probing questions, neither felt any closer to understanding what was behind the problem. Jackie decided to conclude the meeting diplomatically and suggested a follow-up meeting the following week (which, by the way, was exactly the right thing to do in the circumstances).

In preparation for the next meeting, Jackie asked Sonia to reflect on which aspects of her role she enjoyed and which she didn't, and to note down if any of those aspects, or the way she had categorised them, had changed over the past year or so. Sonia completed the exercise and brought her notes to their next meeting. The results of this exercise were also inconclusive, though, because they revealed that Sonia enjoyed her role and didn't find the unenjoyable aspects a particular burden, nor did she feel they had changed over the past year.

So Jackie decided to take a different tack (a master stroke): Together, they mapped a timeline of all the events that Sonia felt had affected her significantly over the past year. On the same chart Jackie asked Sonia to rate her energy levels from 1 to 10 during each of these events. A breakthrough!

It turned out that the fall in Sonia's energy corresponded with the company's announcement of its intention to automate various administrative functions. Jackie then asked Sonia what she thought might be going on here. Although not directly affected by the automation, Sonia explained her anxieties that the new technology and restructuring might result in the redundancy of her role too.

Jackie hadn't even considered this possibility and immediately allayed Sonia's fears. What's more, she added, even if her role was affected in the future Sonia had a number of transferable skills that Jackie considered essential to the firm over the long term.

The raising of these issues provided Jackie with an ideal opportunity to help Sonia clarify her career goals and align her development activities to them, and in so doing further strengthen their working relationship.

Key learnings

Jackie's leadership approach was to leverage and further strengthen her trust relationship with Sonia by taking time to unpack and understand the source of Sonia's concerns. Jackie then used this information to help Sonia review and recalibrate her career goals and development. It also reminded Jackie of the importance of not assuming what your employees might be thinking and of opening up an honest dialogue with them in a safe and trusting environment.