Chapter 10

Structuring unstructured conversations

‘Conversation. What is it? A mystery! It's the art of never seeming bored, of touching everything with interest, of pleasing with trifles, of being fascinating with nothing at all.'

Guy de Maupassant

It might seem paradoxical but there is a structure to having unstructured career conversations. In my experience of coaching leaders, or directly coaching employees in my various roles as a leader, I have found a narrative approach to career conversations to be one of the most effective ways of highlighting patterns and themes and potential pathways forward in career work. It may appear to employees as a ‘freewheeling' conversation. What sits behind this approach, however, is a structure that informs the language, shape and direction of what is discussed and how the emerging information is used. In the context of career conversations, a narrative approach should guide an employee to tell their story by following a chronological sequence of events.

The narrative approach

The narrative approach is particularly effective as it has the potential to unlock in the minds of employees suppressed or forgotten events or achievements they have experienced over the course of their career and life. They could be aware of an event but not regard it as an achievement — a tenure milestone, for example, or an instance when they helped a colleague to succeed.

Helping your employees tell their story assists them in constructing a timeline of the events and milestones that have shaped their career, from leaving school to the present day. It also helps for them to identify individuals — a colleague, previous manager, friend or family member, or even groups of people such as clubs or teams — who may have influenced their decisions or contributed to their career development or advancement in the past.

A narrative approach can be boiled down to helping employees recognise key transition points. It's important, and consistent with the solution-focused principles outlined in chapter 9, to identify and analyse the drivers and contextual influences that have supported previous successful transitions and to use these skills and this knowledge to facilitate future transitions. This can assist in identifying patterns and themes that could again be useful in planning and navigating their future careers. It's a simple but powerful tool for leaders to guide enlightening career conversations with their employees, and you will be amazed at the results when you start applying it. That said, as with all tools it takes practice to master!

Planned happenstance

Unplanned career events, unexpected opportunities and just plain luck can all play a role in our career development and success. Most could point to a bit of luck that helped them along their career journey. John Krumboltz, Kathleen Mitchell and Al Levin devised a career theory called planned happenstance (referred to in chapters 5 and 6). Essentially, they suggest that opportunities can emerge quite unexpectedly when actively doing ‘the right kinds of things' — for example, being prepared and developing one's skills to capitalise on any chance events that may pop up from time to time and to convert them into career opportunities.

In a 1999 paper, Krumboltz and associates identify five key skills that individuals should develop (and leaders can help them do this) in order to generate and make the most of chance events, and to recognise them as career opportunities. These are:

- Curiosity — provides inspiration to help drive the search for learning opportunities. This is fundamental to proactive career development for both leaders and their employees.

- Persistence — means persevering and putting in the effort despite facing obstacles, challenges and setbacks. So many people give up too soon, just as they are about to make a breakthrough, or they leave a company because of a bad boss, only to find the boss leaves the organisation soon after.

- Flexibility — remaining open-minded and agile in our thinking and attitude to changing circumstances, and therefore viewing change as an opportunity for career development. Flexibility is so valuable to leadership and career development.

- Optimism — possessing self-efficacy and seeing new opportunities everywhere. This means having a solutions focus and a positive disposition and outlook, while viewing problems as challenges to act on and resolve.

- Risk-taking — avoiding procrastination, being decisive and taking action even if you're unsure of what might happen. This means not letting fear of failure or the unknown stop you from seeking out and acting on new career opportunities.

In a 2009 paper Krumboltz writes, ‘The Happenstance Learning Theory explains that the career destiny of each individual cannot be predicted in advance but is a function of countless planned and unplanned learning experiences beginning at birth.' Leaders can (and should) add to their employees' learning experiences by encouraging them to be proactive in their career development and be acutely attuned to recognise and act on opportunities that arise.

My own career has benefited from many unplanned events. That said, looking back, I can identify times when I prepared myself, both consciously and unconsciously, to take advantage of these opportunities. I have reinvented myself several times over my career. After leaving secondary school I embarked on a science degree, planned from school because I had an aptitude for it. I disliked it intensely and as a result dropped out of first-year studies. I then entered the business world in the paper industry (unplanned and secured by chance as there happened to be a job opening at the right time). I quickly found I loved both the industry and the business world, particularly sales and marketing.

I went on to study marketing and spent more than 20 years rising through the organisational ranks. I enjoyed several chief executive roles, culminating in my appointment to one of the biggest roles at that time in the Australian paper merchanting industry. Over that period, I took advantage of many opportunities that presented (some planned, some not), but I can point to many occasions on which I very deliberately and purposefully set myself up for success. I also benefited from the great help of a number of very supportive managers, coaches, mentors, colleagues and friends.

In the course of various leadership roles in the paper industry, I became fascinated by human behaviour, career development and leadership theory and practice. This fascination turned out to be stronger than that I held for the paper industry, so I decided to explore a career change. At this stage in my career, I decided I wanted to help many organisations and not just the one I was working for. After researching a number of options, I moved into a highly regarded human resource consulting firm that had all the service lines (and more) that I was interested in.

I spent more than 10 years consulting to a wide range of public- and private-sector clients with a variety of consulting firms and also held a number of senior leadership roles. The verdict was in: I loved consulting! This experience inspired me to co-found and lead my own HR consultancy, specialising in — you guessed it — career and leadership development and HR recruitment.

So I can attest to the fact that planned happenstance theory has played a very real and profound role in my life and career, most often in an extremely positive way! Doing the ‘right things' doesn't guarantee success, though I (along with my clients) have found it definitely helps! All leaders have the opportunity to help their employees do the same.

The key is to keep an open mind, expect the unexpected, recognise when these unplanned events arise, treat them as a gift and take advantage of them by taking appropriate action.

In the introduction of this book, I called out the need for leaders to be agile in their approach to how, when and where they engage their employees in career conversations. Common sense tells us that these conversations should be held in a confidential environment, free of distractions, but in practice this is not always so easy to manage in today's world of open-plan offices and fast-paced, dynamic workplaces. Sometimes leaders just need to grab the ‘moment' as it arises. This is a good example of acting on or using planned happenstance theory. Putting off a career discussion to a later date could very well mean it ends up being too late to save an employment relationship. Seize the moment in this scenario!

As a leader you will most likely diarise regular career discussions, but sometimes great career conversations result from unplanned, in-the-moment meetings. I want to emphasise that while scheduled career development meetings work well, so too do career conversations done ‘on the fly'. As a leader, you just need to recognise these opportunities and make time for them when needed. This is easier said than done, but an imperative nonetheless. Putting off a career conversation can be perilous to employee engagement and retention. You need to exercise judgement on what can wait and what can't. This is a fundamental and crucial leadership capability that, from my experience, remains in short supply!

Change and transition in careers

Transitions and change are not always linear and are not always easy to create and sustain, yet change is nearly always a necessary ingredient in career growth and development. Making and dealing with change can feel difficult and even daunting. As discussed in chapter 2, after working with many individuals (and groups) going through significant change, I have come to understand that people do not fear change but rather fear being changed.

Advocating change therefore may well be required in some career conversations. This is a crucial skill in itself because leaders can play a critical role in leading, advocating and managing change for both individuals and their organisations.

When thinking about change and how to inspire and encourage it, leaders can apply a number of useful models, some of which are outlined here.

Bridges' model of transition

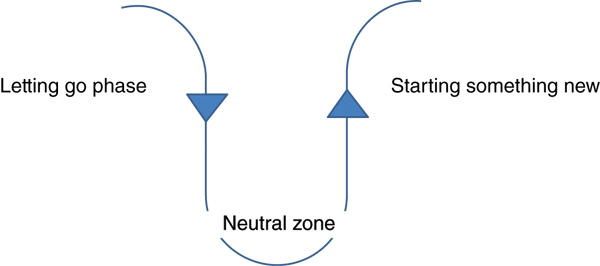

For change consultant William Bridges, transition is about starting something new, which implies letting something go. I have adapted Bridges' transition model in figure 10.1, which points to a neutral zone between letting go and starting something new to explain how important these phases are to career transition and development. The neutral zone can be thought of as an ‘ambivalence phase' that can be frustrating for employees (and their leaders!) but is an important one to move through. In my experience, we can be at our most creative in times of uncertainty, so ambivalence is not a bad thing. It can be quite useful and is certainly normal.

Figure 10.1: Bridges' transition model

Adapted from W. Bridges and S. Bridges (2017), Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change (rev. 4th edn), Hodder & Stoughton, London.

Paradoxically, leaders have an opportunity to help their employees embrace uncertainty and ambiguity as a pathway to clarity. A feeling of complete exasperation from not seeing a way forward can trigger a breakthrough, when we discover exactly what to do! This is when leaders can play a vital role in helping their employees, particularly if they feel stuck in their career, to move forward towards starting something new.

Grant's ‘House of Change' model

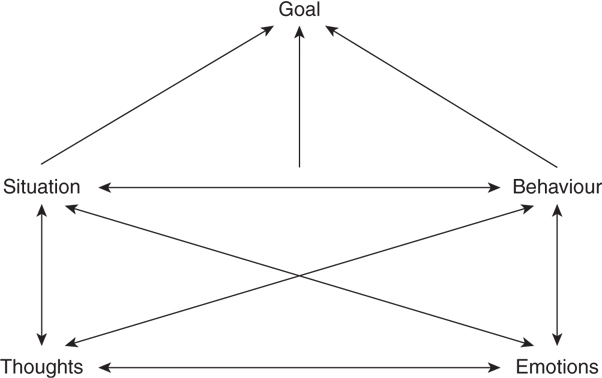

Anthony Grant believes that to sustain real and lasting change in our lives we need to change our thoughts, feelings and behaviour, which interact with our situation to bring about change and enable goal achievement (see figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2: Grant's ‘House of Change' model

Source: J. Greene & A. Grant (2003), Solution-Focused Coaching, Pearson Education, UK.

Grant points out that if the foundations of the house aren't firm, then the whole structure including the roof (the goal) are at risk. More to the point, changing only one or two of the pillars won't facilitate the change we may be seeking. For example, if we change the way we think about something but fail to change our behaviour, then we jeopardise the necessary change. If we change our situation without changing how we think, feel and behave, then making and sustaining the change required to achieve our goal becomes highly unlikely.

Grant's model asserts that we need to redesign all four pillars of the house to effect and sustain the change required to reach our goal. This concept is particularly useful for leaders seeking to help employees who may be able to set goals but who struggle to maintain their focus on them. Leaders can observe this in an employee who experiences frequent, short-lived forays in their career progress or multiple employers over a relatively short time period. Applying the ‘House of Change' concept in these circumstances, leaders can help their employees to examine and, if necessary, redesign their house.

A model of intentional change

The process of change, whether in yourself or in others, can seem complicated, challenging and far from easy to achieve and sustain. I'd love a dollar for every time I've been asked by an exasperated leader, ‘Why did they do that?' when talking about an employee's ‘inexplicable' behaviour.

Change is a very well researched topic, yet many leaders are still bewildered by how to lead and manage it. The problem isn't change itself, so much as how people think about it. By that I mean many leaders have a tendency to overcomplicate it. This can be seen when people set goals that require moving mountains then get frustrated and even give up when the goal remains elusive. Who can blame them? For example, having just taken on an entry-level leadership role for the first time, they immediately set their sights on progressing to a senior management position within 12 months. Such an aspiration is unrealistic and is bound to lead to frustration and disappointment. Here is where leaders can help their employees recalibrate their goals, as discussed in chapter 6.

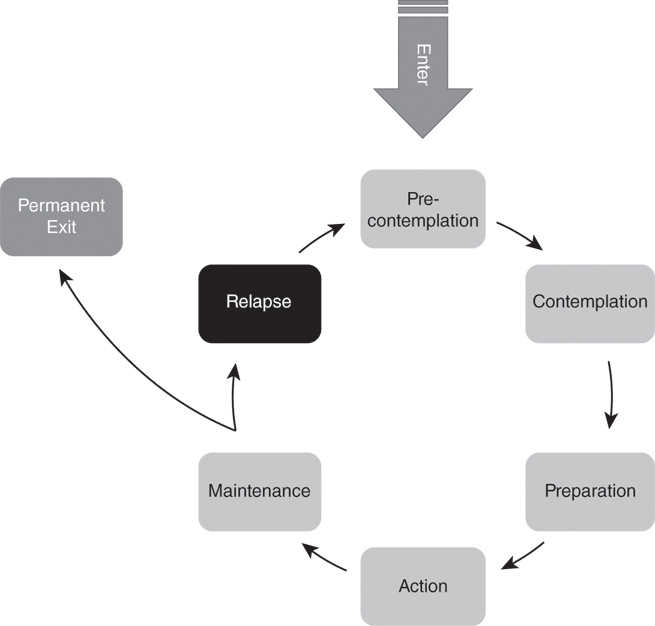

Change experts today generally accept that effective change involves several key stages. James Prochaska, John Norcross and Carlo DiClemente developed their Transtheoretical Model to conceptually articulate the process of intentional behaviour change that focuses on the decision-making pathways and can be applied to almost any area of an individual's life. Figure 10.3, adapted from their model, depicts change behaviour as a continuing loop of actions that begins when we first start thinking about making a change (contemplation).

Figure 10.3: a model of intentional change

Pre-contemplation denotes the time before we consider making a change. Once we have thought about making a change (contemplation), we start preparing to make the necessary adjustments (preparation) and taking deliberate steps (action) towards change behaviour. From there we enter the maintenance stage, during which we need only a low-energy approach to prevent a relapse. Better still, we exit the loop having successfully made and sustained the change we wanted, which has now become a permanent part of our personality. As this model highlights, relapse is a normal part of the behaviour change process.

It's rare that change is a linear progression uninterrupted by setbacks. For example, it's not unusual for smokers to experience numerous relapses when trying to quit smoking. In fact, the framework of this model has been used in a number of studies in relation to smoking cessation. In recent times Australian anti-smoking campaigns have featured television advertising that stresses that relapse is normal and encourages those trying to quit to keep trying.

As an example of the model's application in a career scenario, a performance review holds a surprise and to avoid holding back potential career advancement we are asked to change our professional behaviour in some way (pre-contemplation, since we weren't aware of the need to change). The boss provides compelling behavioural examples of why this is necessary; we accept the feedback and start to think about what needs to happen (contemplation), and we engage a coach to help make the change (preparation).

We work positively with our coach and proactively seek feedback on our progress (action). Having successfully changed our behaviour, we incorporate this into our work style (maintenance, and exit the process). Perhaps after making good progress we temporarily slip back into our old ways (relapse). We contemplate re-engaging the behaviour change process so the change loop continues.

Failing is great for success!

Failing nurtures courage and helps build resilience. It is surely one of the best ways of learning. Indeed, I believe that failure should be a compulsory subject in every business school or university.

Committed to the benefits of failure, The New York Times reported that Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, added failure to the syllabus in 2017. Rachel Simmons, a leadership development specialist at Smith, remarks, ‘What we're trying to teach is that failure is not a bug of learning, it's the feature.'

The initiative, called ‘Failing Well', is aimed at destigmatising failure and teaching students how to cope with and learn from disappointments and setbacks. The program includes workshops on impostor syndrome along with discussions on perfectionism and fostering resilience. Those who fall prey to impostor syndrome are convinced they are ‘frauds' and undeserving of success and recognition, despite evidence to the contrary. Instead, they attribute to luck or good timing their ability to deceive others into thinking they are more capable or intelligent than they really are.

Perfectionism, while driving success, can also hold individuals back. For example, if leaders project their exacting high standards onto their protégés, this can potentially interfere with their employees' own development and confidence, particularly if, in the leader's eyes, they don't ‘measure up'. Rachel Tyson, psychologist with Incorporate Psychology, has written an excellent article on imposter syndrome that I encourage you to read (see References and further reading at the back of this book).

Smith College encourages students to take healthy risks (and feel comfortable doing so), to explore new disciplines and to try new experiences. Students who complete the program receive a Certificate of Failure, which declares that it's possible to ‘screw up, bomb or otherwise fail at one or more relationships ... and still be a totally worthy, utterly excellent human'.

In a career context, it's important for leaders to recognise that not every career conversation will ‘make a difference' but every conversation will contribute to progress, even if this is not apparent at the time. Progress, no matter how small, matters and is valuable. Baby steps are just as important as giant leaps; indeed, they are often more useful to making and measuring progress.

This is where leaders will find a good dose of humility — and, at appropriate times, self-disclosure of their own failures — very useful. By showing employees how disappointments, failures and setbacks contributed to their career success, they can role model their intrinsic benefits to overall career development. This can help build confidence in their protégés, allowing them to feel more comfortable in making their own mistakes. As is clearly highlighted in Prochaska, Norcross and DiClemente's model, by stumbling and reflecting we are set up to make navigational changes and limit the recurrence of unwanted experiences.

The key is to be empowered, not imprisoned, by our mistakes. When our mind is in a state of confusion, we can be at our most creative! The way forward might already exist but be disguised. Sometimes we just need to take a leap of faith and see what happens! Leaders can play a powerful part in helping their employees break free of the confines of convention, stereotypes and norms, and their own usual thinking patterns, and cut a new path forward.

The GROW model — a useful tool for structuring effective career conversations

The GROW model provides a sensible, easy-to-follow and effective framework for narrative-style career conversations in which the leaders collaboratively co-construct the way forward with their employee.

The original authorship of this model is unclear, though Sir John Whitmore, Alex Fine and Graham Alexander all made significant contributions to its development. Max Landsberg also described it and its applications in coaching in his book The Tao of Coaching.

The GROW model is broken down into four elements.

Goals

Setting SMART goals (see chapter 6).

For leaders this might be as simple as asking, ‘What would you like to achieve or leave with at the conclusion of this meeting?'

Reality

The leader checks the employee's current reality by exploring what's really going on and comparing this with what they might wish to be happening. This may include asking what's stopping them achieving their goals and whether they would like to modify their goals or choose a new one. The leader might simply ask, ‘What's happened since we last met?' or ‘What has happened in the past week or two?'

Options

The leader helps their employee to identify and consider possible options. It's empowering to have options; conversely, it's disempowering to feel no options exist! Collaborative brainstorming is a helpful activity here. The leader may ask, for example, ‘What do you see as realistic options?' or ‘What else could you do?' or ‘What has worked in the past and what do you see as the next step?' These questions are designed to put the power in the hands of the employee to help them move forward positively, creatively and practically.

Wrap-up

This is where leader and employee plan the next steps. It will usually involve considering obstacles to achieving the goals and concrete strategies to overcome them. This commonly takes the form of action planning with specific, clearly assigned, goal-oriented actions with target dates for completion.

Figures 10.4 and 10.5 (overleaf) illustrate simple GROW and RE-GROW templates.

|

Goal(s) Remember to make them SMART. Ask: ‘What would you like to achieve?'

|

|

Reality Checks the current reality and goals. Ask: ‘What's happened since we last met?'

|

|

Options Brainstorm realistic options and stay solution focused. Ask: ‘What's worked in the past?'

|

|

Wrap-up Plan the next steps. Consider possible obstacles and how to overcome them. Ask: ‘What specific steps will you take next and when?'

|

Figure 10.4: the GROW template

Source: Adapted from A. Grant and J. Greene (2003), Solution-Focused Coaching, Pearson Education, UK.

|

Review and Evaluate … actions, successes and outcomes towards goals attainment. Remember to stay solution focused. Ask: ‘What progress have you made towards your goals since we last met?'

|

|

Goal(s) Remember to make them SMART. Ask: ‘What would you like to achieve?'

|

|

Reality Check the current reality and goals. Ask: ‘What's happened since we last met?'

|

|

Options Brainstorm realistic options, remembering to stay solution focused. Ask: ‘What has worked in the past?'

|

|

Wrap-up Plan the next steps. Consider possible obstacles and how to overcome them? Ask: ‘What specific steps will you take next and when?'

|

Figure 10.5: the RE-GROW template

Source: Adapted from A. Grant and J. Greene (2003), Solution-Focused Coaching, Pearson Education, UK.

Ben's career story

Ben is a technical expert in his field. Based on his success, he was moved from research and development into sales and very soon after, in mid career, was promoted to sales management. Ben hadn't applied for a job since his employer hired him in their graduate intake, more than 20 years ago. He took advantage of career opportunities as they presented and his career flourished, but now he was struggling to find meaning in his work. His passion for his work had dipped and he found he lacked motivation and energy, as was evident to his peers.

Ben approached Human Resources for help. A recent 360-degree feedback survey indicated that his subordinates had also noticed a drop in Ben's passion and energy. His work performance, along with sales revenue, had shown a drop over the last three quarters. Human Resources were sympathetic. They suspected that sales management wasn't a good fit for Ben and probed further for possible reasons for this. Ben's HR business partner encouraged him to have a career conversation with his manager, Adam.

Ben wasn't overly enthusiastic and avoided this conversation for some time, until finally Adam called Ben into his office and asked him straight out what was wrong. Adam referred to Ben's recent 360-degree survey feedback, flagging sales performance and noticeable lack of energy. Ben acknowledged he was struggling in his role as sales manager and didn't know why he lacked the motivation to fix things. Adam was frustrated with Ben but needed to find a solution to the falling sales revenues fast. He told Ben, using quite direct language, to ‘sort himself out and pull his socks up or he'd be replaced'.

Ben left this discussion upset and was at a complete loss to know what to do next. He returned to Human Resources to report the outcome but was told there was little more they could do to help. They urged him to try to work things out with Adam.

Ben saw that neither Adam nor HR were going to be useful to him, so he sought the help of a professional career coach. The coach used a narrative approach in working with him and had him complete the career drivers exercise. Taking a structured approach of debriefing his career driver results combined with the narrative-style conversations helped Ben to unpack his current situation, rediscover his career motivators and demotivators, and refocus on his passion, technical expertise.

It became apparent that no-one in Ben's company had asked if he wanted to be sales manager; rather, they just expected him to jump at it because it meant a promotion and more money. Ben had been flattered by the confidence they showed in him and, although he felt uncertain about it, accepted the role. Ben's career coach helped him to uncover that his technical expertise was his number one career driver. The lack of opportunity for this career driver in his sales management role was a major source of his discontent, which helped explain his lack of motivation and corresponding performance deficit.

A few weeks later, having regained his career focus and clarity, Ben returned to Adam and requested a transfer back to research and development. Adam was relieved by Ben's decision, which offered the bonus of allowing the company to retain a high-performing and talented employee.

Ben was amazed by how a structured approach to his career discussions and career development had, in a relatively short space of time, allowed him to explore and refine his true passion.

Key learnings

While Ben and his company both came out winners, there were multiple failure points along the way. These began with Ben's promotion into a role without a robust selection process and were compounded by the organisation's failure to provide career support when the error was first suspected. Those failures were exacerbated when Ben's boss threatened him with dismissal and Human Resources offered little follow-up support.

Although Ben eventually found success, he could have been saved from an unhappy period in his career, and the company could have avoided the revenue losses resulting from his subpar performance, if Ben's manager and/or Human Resources had used some of the career tools discussed in this book.