Appendix 1

Opera recording: practices at Decca from the 1950s to the 1990s

Although this is not a history book, there are a few occasions where describing how things were done during a previous era can be useful in understanding how those iconic recordings were achieved and how older practices compare with where we are today. Recording opera in the studio, especially in the way it was done at Decca during this period, is an extremely expensive undertaking. For financial reasons, a great deal of opera recording today is captured live from a theatre, even if there is subsequent editing between performances (see Chapter 16).

Philosophically, it is possible to approach recording opera much as one would an oratorio, without taking into account the fact that an opera is a staged genre where the singers move around during the action. However, under the initial influence of John Culshaw, one of the additional goals of the Decca studio opera recordings of the 1950s to 1990s was to capture the depth and perspective of the stage behind the orchestra and to position the singers according to the dramatic action at the time. In this way, it was seen as more akin to recording a play as it was performed and not simply recording actors reading from a playscript. Additionally, most of the theatrical effects included in the score and stage directions were included at the time of the recording. Things that would be added later were small effects such as clocks, bells, and the occasional sword fight, although offstage chorus might also be recorded separately (such as that for ‘Nessun Dorma’ from Puccini’s Turandot (Decca, 1972); see Figure A1.9).

There are four elements to capturing staged opera as a recording session:

- 1Stage set-up.

- 2Chorus set-up.

- 3Orchestral set-up.

- 4Live offstage effects.

Additional practical considerations are communications between control room, conductor, and stage and the level of detail required to repeat stage positions for every take.

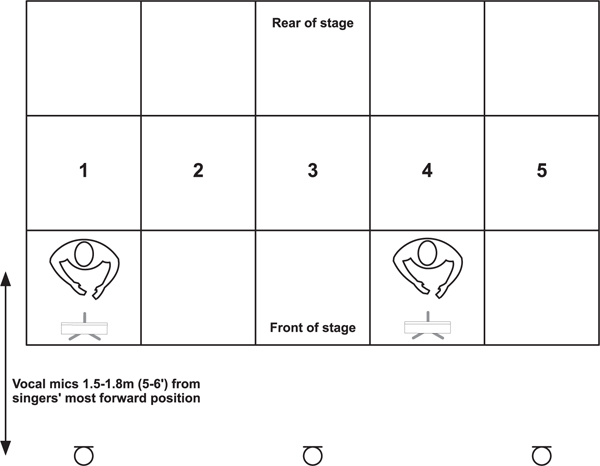

A1.1 The stage set-up

The stage might already be present in the hall, such as at Kingsway Hall, where around 80 chorus members could be accommodated behind the stage or on adjacent balconies if more singers were needed. Where there was no stage already in situ, a staging area was placed behind the orchestra, and it was designed to make replicating stage moves straightforward. During the later 1950s and early 1960s, a grid was marked out in squares on the stage floor, with each square measuring about 1.5–1.8 m (5′ to 6′) along each side. The stage measured at least five squares wide and three deep, and the singers had to move between the grid squares as part of the recording choreography. Vocal microphones were set up at three positions across the front of the stage in front of positions 1, 3, and 5. See Figure A1.1 for the grid layout and Figure A1.2 for a photo of an early recording with Kirsten Flagstad in which the stage grid is clearly visible.

From the mid-1960s onwards, Decca moved to a five-microphone stage (see Figure A1.3) to avoid singers losing focus if they were standing in areas 2 and 4 on the grid. Once the five-microphone set-up was in use, the floor grid was discontinued as the microphones were used as lateral reference positions instead.

The microphones were numbered 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10, and each microphone stand or its associated music stand was clearly labelled with a large reference number. Odd-numbered stage position references were located in between the microphones, and all choreographed stage positions were marked in the scores that were used by the conductor, producer, and engineer. Most of the stage directions were lateral movements, but in the event of needing a more distant sound, the singer would be asked to step back a bit or even to turn around and face away from the microphones. When standing closest to the front of the stage area, the singers were around 1.5–1.8 m (5′ to 6′) away from the microphones.

Figure A1.1 Shows 5 x 3 stage grid with three vocal microphones

Figure A1.2 The 1957 recording of Die Walküre in Sofiensaal, Vienna, with Kirsten Flagstad and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Hans Knappertsbusch.1 The stage grid layout is visible, along with the stage bar for mounting soloists’ microphones and the experimental baffled tree.

Photo: Courtesy Decca Music Group Ltd.

The assistant producer would spend the session on the stage area to make sure that the singers were always on the correct microphones, and became known as the ‘collie’ because of the parallel with herding sheep. The engineer followed the same cues in his own score in order to know which of the stage microphones needed to be faded up at any time; the five microphones were not left open at all times, as this would have confused the orchestral image. For large stage movements of singers, the engineer would have to crossfade between adjacent microphones, although some smaller movements could be simulated by panning the microphone while the singer stood still. Singers varied greatly in their ability to sing and move at the same time, with many only able to move first and sing afterwards.

Figure A1.3 Five-microphone set-up with no stage grid. Microphone numbers are shown in bold (2, 4, 6, 8, 10) with the in-between stage positions taking the odd numbers.

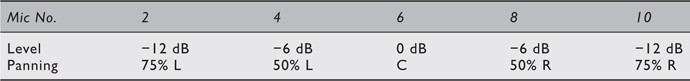

The additional microphones were used to have an effect on the soloist’s sound that was similar to the use of two spot microphones. When faded up in appropriate amounts, they produced some width and bloom around the singer so that he or she did not sound like a dimensionless point source. For a singer standing centrally, nearest to microphone 6, the relative gains and panning of the microphones would be roughly as shown in the table in Figure A1.4.

As can be imagined, the amount of fader moves needed to keep track of the singer (or singers) made this very intensive work for the engineer, particularly in the days of recording straight to stereo on session. Decca would use two balance engineers: one for the orchestra and one to concentrate on the soloists’ microphones only. Recordings up to 1975 were recorded to four tracks: two tracks for the orchestra and two tracks for the chorus and soloists.

The vocal microphones used were M49s and KM56s in the early days, KM64 cardioids in the 1960s, and KM84s for most of the 1970s through the 1990s. In the Sofiensaal, Vienna, these were mounted on a single wide stage bar at a little above mouth height so the singers could still see the conductor, although this method meant they were unable to accommodate singers of very different heights. As noted in Chapter 16, positioning just below the mouth works well to reduce tonal variation where singers have a tendency to either look straight ahead or slightly down as they glance at the score. Figure A1.5 is from a session from the Sofiensaal that shows the bar-mounted microphones and also an acoustic screen behind the orchestra that was rarely used (see section A1.3).

Figure A1.4 Gains and panning for a singer standing centrally on a five-microphone stage

An obvious development of the five-microphone opera stage would be to replace each of the three inner single microphones with a pair, and this forms the basis of the stage coverage technique for capturing live opera at the Royal Opera House outlined in Chapter 16.

Figure A1.6 shows the sessions for the 1993–1994 recording of Berlioz’s Les Troyens with Dutoit and the OSM,3 presenting the stage layout which uses seven soloists’ microphones in this case.

A1.2 The chorus set-up

The chorus would be placed behind the soloists’ stage area, and it was most effective when placed at least 10 m away from the orchestra. This meant that the spill between chorus and orchestra became very de-correlated, and they could be approached as separate sources that would later be laid on top of one another in the mix. Another row of microphones mounted on a bar was used to cover the chorus; in the early days, there would have been only three chorus microphones because of channel limitations on the mixing desk. This was later expanded to five microphones as for the soloists (see Figure A1.7). Figure A1.8 shows a session from The Flying Dutchman with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra that reflects this layout.

A1.3 The orchestra set-up

The orchestra set-up was very much as we might expect from the Decca orchestral recording tradition but with a few minor changes. Because there were also choir and soloist microphones open in the room, more indirect orchestral sound was picked up, and getting enough detail from the orchestra became more difficult. As a result, the orchestral microphones were placed slightly closer than for a purely orchestral session, with the main microphones mounted about 7.5 cm (3″) lower than the normal tree height.

During the period 1967–1972, Decca’s opera recordings were made with the six-microphone tree array that is described in section 8.6; the first opera to go back to using the ‘classic’ Decca five-microphone tree was Turandot in 1972.5 For this particular recording, screens were added behind the woodwinds to reduce orchestral spill into the soloists’ stage microphones. These were about 2.25 m (7′4″) high from the orchestral floor, so the singers on stage could see over the top, but this arrangement was not very conducive to an enjoyable performance experience for the singers or to good communication between singers and conductor. The effect of the screens was also slightly audible on the voices, and their use did not catch on, although the reversion to the three-microphone tree endured. A copy of the set-up layout for Turandot is shown included in Appendix 3.

Figure A1.5 The 1967 recording of La clemenza di Tito at the Sofiensaal, Vienna, with István Kertész conducting the Vienna State Opera Orchestra,2 showing soloists’ microphones on a bar at the front of the stage and microphone numbers beneath

Photo: Elfriede Hanak; courtesy Decca Music Group Ltd.

Figure A1.9 shows a view of the stage area from the Turandot recordings, with the chorus behind the soloists. The acoustic screens are just visible in the bottom right-hand corner.

Figure A1.6 Les Troyens sessions in Montreal, 1993–1994

Photo: Jim Steere; courtesy Decca Music Group Ltd.

A1.4 Offstage effects

Offstage effects were generally performed live, thus capturing a real sense of distance and not one created by artificial reverb or other processing. Part of the reason for this was because of constraints on track numbers and the lack of technology such as digital reverb; effects were often performed in a convenient stairwell to provide the right sense of distance or reverb. Effects performed in a different room or stairwell needed to be cued in at the right time in the score; the communications required to co-ordinate the operator are touched on in section A1.5. In old theatres such as Drottningholm, live theatrical effects could be captured as part of opera recording; the old-fashioned way of creating a thunder effect in a theatre was by rolling cannonballs across the stage. More unusual effects were created as required; a well-known example outlined in Culshaw’s book Ring Resounding6 was the use of a slowed-down recording of a bowling alley strike to represent the fall of Valhalla.

Figure A1.8 A session from The Flying Dutchman with Sir Georg Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus in Medinah Temple in 1976.4 The chorus is placed in the lower balcony, and a row of chorus microphones is clearly visible.

Photo: Courtesy Decca Music Group Ltd.

A1.5 Communications and control room management

Communications and logistics requirements for studio opera recording were complex and expensive, and in the days before mixing desks had assignable groups, an additional engineer was used to manage the large number of channels and active faders involved in mixing live on session. The nominally senior engineer usually dealt with the orchestra, any sound effects, and the overall balance, and the second engineer usually managed the soloists and chorus. This was not a rigid system, however, and was open to change according to personal preferences.

The main areas that needed to be linked by efficient communication systems were the control room, the conductor, and the stage area (where the assistant producer was stationed). Additional communications would be needed for any offstage performance, whether this was a chorus with an assistant conductor, a soloist, or sound effects operator. Phone links were set up between all areas, and cameras relayed live pictures of the stage area and the conductor back to the control room. The stage cameras would show a front view, but where possible a side view would be added as this made it easy to see how far back the singers were standing. The assistant producer on the stage area would also be equipped with headphones so that stage directions could be relayed quickly. The ‘Pellowephone’ was a mini-telephone exchange that enabled all the phones to talk to one another (see Figure A1.10).

Within the control room, two balance engineers and a producer had to sit so that everyone could hear, see the video monitors, and communicate with one another. On Decca recordings, the producer sat to one side of the centrally seated engineers rather than behind them in the best monitoring position, reflecting the non-hierarchical and collaborative way of working that had evolved at the company. Although as the most senior person he was nominally in charge, much of the decision-making and approach to the recording was down to discussion amongst the team. There was always a strong culture of sharing recording techniques and ideas between engineers at Decca, which went a long way to creating a familial atmosphere and the development of a certain consistency of house sound. If an engineer at any level discovered something that worked well, it would be shared with the others, and this provided a very fertile training ground for younger engineers and also kept the established engineers open to new suggestions. The need for two balance engineers to deal with live opera balancing was easily managed within this sort of collaborative culture without the clash of egos that might have arisen between engineers elsewhere. Even when John Culshaw was producing, the producer’s role was not seen as the great impresario set apart from the others, but as part of the team, so open to discussion and finding the best way forwards.

Figure A1.10 Communications equipment – the ‘Pellowephone’ telephone exchange in the control room

Photo: Mark Rogers.