Your Z6 has more special features than a DVD box set. In designing its all-new Z-series camera platform, Nikon drew on its expertise in providing leading-edge capabilities in the digital single-lens reflex realm, and leveraged the advanced features possible with mirrorless technology. As a result, your Z6 has the kind of totally silent shooting that’s not possible with conventional dSLRs and their clunky mechanical mirrors. You won’t find in-body image stabilization in any Nikon dSLR, and cool features like focus-shift “stacking,” and split-screen live view are currently available only in high-end models like the Nikon D850. Other capabilities built into your Z6 are more common, but have some special applications in a mirrorless model like the Z6. So, I’ve saved some of my favorite advanced techniques that the Z6 excels at for this chapter, which devotes a little extra space to some special features of the camera. This chapter covers GPS techniques and special exposure options, including time-lapse photography and very long and very short exposures. You’ll even find an introduction to using SnapBridge and focus stacking.

Continuous Shooting

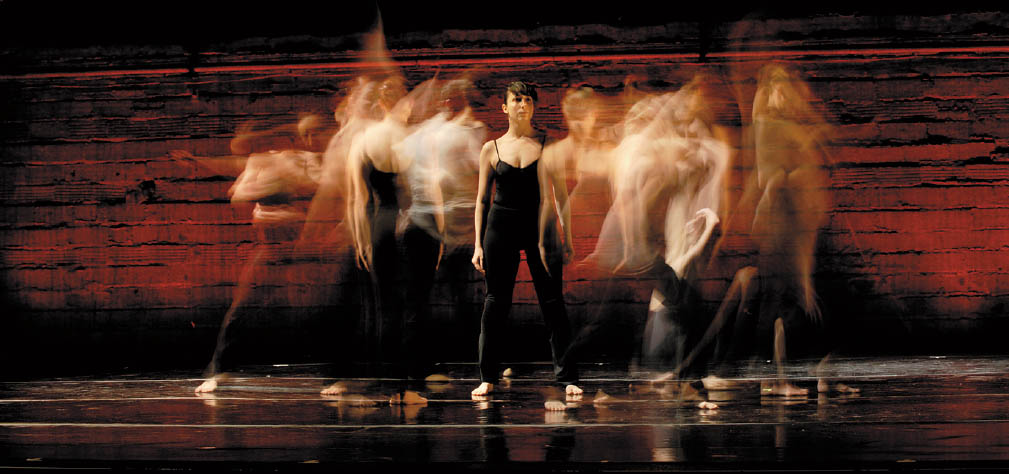

Even a seasoned action photographer can miss the decisive instant during a football play when a crucial block is made, or a baseball superstar’s bat shatters and pieces of cork fly out. Continuous shooting simplifies taking a series of pictures, either to ensure that one has more or less the exact moment you want to capture or to capture a sequence that is interesting as a collection of successive images, as seen in Figure 6.1. Your Nikon Z6 can capture up to 12 fps using Continuous H (Extended) mode for JPEG or 12-bit NEF (RAW) images.

I use continuous shooting a lot—and not just for sports. The upside is that I may be able to capture an image or a sequence that I could never grab in single-shot mode. The downside is that I end up with many shots to wade through to find the “keepers.” I know that sounds like I am using my Nikon like a machine gun, and hoping that I capture a worthwhile moment through sheer luck, but that’s not really the case. Here are some types of scenes where the rapid-fire capabilities of the Z6 pay big dividends.

Figure 6.1 Continuous shooting allows you to capture an entire sequence of exciting moments as they unfold.

- Action. Of course. If you’re shooting a fast-moving sport, continuous shooting is your only option. But it’s important to remember that lightning-quick bursts don’t replace good timing. A 90 mph fastball moves about 11 feet between frames when you’re shooting at the Z6’s maximum frame rate of 12 fps. A ball making contact with a bat is still likely to escape capture. Continuous shooting may provide its best advantages in capturing sequences, so that each shot tells part of the story.

- Bracketing. I almost always set my camera to continuous shooting when bracketing. My goal is not to capture a bunch of different moments, each slightly different from the last, but, rather, to grab virtually the same moment, at different exposures (or, less frequently, with different white balance or Active D-Lighting settings). I can then choose which of the nearly identical shots has the exposure I prefer, or can assemble some of them into a high dynamic range. The high burst rate of the Z6 makes bracketing and hand-held HDR (high dynamic range) photography entirely practical. Software that combines such images does an excellent job of aligning images that are framed slightly differently when creating the final HDR version.

- Ersatz vibration reduction. I shoot three or four concerts a month, always hand-held, and always with VR turned on. I usually add a little simulated vibration reduction by shooting in continuous mode. While I have a fairly steady hand, I find that the middle exposures of a sequence are often noticeably sharper than those at the beginning, because my motions have “settled down” after initially depressing the shutter release button. My only caution for using this tool is to limit your shots during quiet passages, and avoid continuous shooting during acoustic concerts, if you are not using the electronic shutter. The rat-a-tat-tat of a Nikon Z6’s mechanical shutter will earn you no friends. Activating the electronic shutter from the Photo Shooting menu is a better idea in such venues.

- Variations on a theme. Some subjects benefit from sequences more than others, because some aspect changes between shots. Cavorting children, emoting concert performers (as described above), fashion models, or participants at weddings or other events all can look quite different within the span of a few seconds.

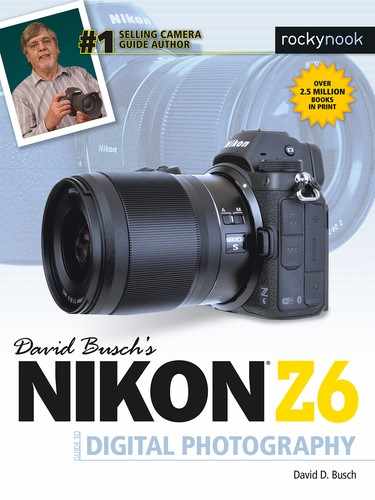

To use the Z6’s continuous shooting modes use the i menu and navigate to Release Mode to select Continuous (L), Continuous (H), or Continuous (H) Extended. When you partially depress the shutter button, the viewfinder will display at the right side a number representing the maximum number of shots you can take at the current quality settings—the Shots Remaining indicator will show [r35] or some other value. That number will decrease as you take photos and they are stored in the Z6’s buffer before being dumped onto the memory card. As the card catches up, the number will increase again. Nikon’s estimates for the number of shots you can take consecutively with Image Area set to full-frame FX (2624) and the (currently) fastest-available Sony G-series XQD card are as shown in Table 6.1. Using Fine *, Normal *, or Basic * will reduce these numbers. In practice, if you shoot JPEGs using Continuous (H), the Z6 writes fast enough that the buffer is virtually “bottomless.”

Naturally, there are factors that can reduce both the number of continuous shots, as well as the frame rate. If you use slower XQD cards or shoot RAW + JPEG, expect some performance penalties. Slow shutter speeds obviously reduce frame rates; you can’t fire off 5.5 frames per second with a 1/4-second shutter speed, for example.

The frame rate you select will depend on the kind of shooting you want to do. For example, when shooting multiple exposures, if you’re carefully planning and composing each individual exposure, you might not want to shoot continuously at all. But if your subject is moving, your double exposure might be more effective if you select a frame rate that matches the speed of motion of your target. Here are some guidelines:

- 9–12 fps. In High-Speed Continuous (Extended) you can capture JPEGs at up to 12 fps or 14-bit NEF (RAW) at 9 fps. Use these for sports and other subjects where you want to optimize your chances of capturing the decisive moment. Perhaps you’re shooting some active kids and want to grab their most appealing expressions. This fast frame rate can improve the odds. However, there is no guarantee that even at 12 fps the crucial instant won’t occur between frames. For example, when shooting major league baseball games, if I want to photograph a batter, I keep both eyes open, and keep one of them on the pitcher. Then, I start taking my sequence just as the pitcher releases the ball. My goal is to capture the batter making contact with the ball. But even at 12 fps, I find that a hitter connects between frames (remember that 90 mph fastball jumps 11 feet between shots). I usually must take pictures of a couple dozen at-bats to get a shot of bat and ball connecting, either for a base hit or a foul ball.

The very fastest continuous speeds come with some tradeoffs. The Z6 does not recalculate exposure between shots; it is fixed at the exposure calculated for the first image in the sequence. Flicker reduction is not used in this continuous mode, so the display is not updated in real time, and you may notice some lagging. You can set Custom Setting d11: View All in Continuous Mode to Off, and the display will blank during a sequence, giving you the fastest speed, but no feedback. I always leave d11 set to On.

- 4.0–5.5 fps. High-Speed Continuous has a top rate of 5.5 fps, but you can choose any setting between 1 and 5 fps for Low-Speed Continuous. A slightly slower rate can be useful for activities that aren’t quite so fast moving. But, there’s another benefit. If your frame rate is likely to be slowed by one of the factors I mentioned earlier, using a moderately slower frame rate can provide you with a constant shooting speed without the buffer filling.

- 1.0–3.0 fps. You can set Low-Speed Continuous to use a relatively pokey frame rate, too. Use these rates when you just want to be able to take pictures quickly and aren’t interested in filling up your memory card with mostly duplicated images. At 1 fps you can hold down the shutter release and fire away, or ease up when you want to pause. At higher frame rates, by the time you’ve decided to stop shooting, you may have taken an extra three or four shots that you really don’t want. Slow frame rates are good for bracketing, too. You’ll find that slower frame rates also come in handy for subjects that are moving around in interesting ways (photographic models come to mind) but don’t change their looks or poses quickly enough to merit a 7 fps burst.

- Movie stills. As I’ll note in Chapter 14, you can take up to 50 single or continuous still photos in JPEG Fine * format using the dimensions of the movie frame (e.g., 1920 × 1080 pixels) while capturing video. Do that by enabling the shutter release button in Movie mode, if necessary, using Custom Setting f2: Custom Control Assignment > Shutter-release button. (The default setting is Take Photos.) When the Photo/Movie switch is set to the Movie position, pressing the Release Mode button produces only two choices: Single frame or Continuous.

- Single-frame release mode. You can take pictures without interrupting movie shooting; only one photo is taken each time the shutter release is pressed.

- Continuous mode. The Z6 will capture images continuously for a period of up to three seconds while the shutter button is held down. The frames-per-second rate will depend on the frame rate you’ve selected for movie shooting. However, continuous capture works only when you are in movie mode, but not actually capturing video. During video recording, only a single image will be captured even if the release mode is set to Continuous.

A Tiny Slice of Time

Exposures that seem impossibly brief can reveal a world we didn’t know existed. Electronic flash freezes action by virtue of its extremely short duration—as brief as 1/50,000th second or less. The Z6’s optional external electronic flash unit can give you these ultra-quick glimpses of moving subjects. You can read more about using electronic flash to stop action in Chapter 9.

Of course, the Z6 is fully capable of immobilizing all but the fastest movement using only its shutter speeds, which range all the way up to 1/8,000th second. Indeed, you’ll rarely have need for such a brief shutter speed in ordinary shooting. (For the record, I don’t believe I’ve ever used a shutter speed of 1/8,000th second, except when testing a camera’s ISO 25800 or higher setting outdoors in broad daylight.) But at more reasonable sensitivity settings, say, to use an aperture of f/1.8 at ISO 200 outdoors in bright sunlight, a shutter speed of 1/8,000th second would more than do the job. You’d need a faster shutter speed only if you moved the ISO setting to a higher sensitivity (but why would you do that, outside of testing situations like mine?). Under less than full sunlight, even 1/4,000th second is more than fast enough for any conditions you’re likely to encounter.

Indeed, most sports action can be frozen at 1/2,000th second or slower, as you can see in the image of the soccer player in Figure 6.2; I caught the two soccer players at the peak of the action, so 1/800th second was easily fast enough to freeze them in mid-stride. At ISO 100, I used f/5.6 on my 70-200mm f/2.8 lens to allow the distracting background to blur.

Of course, in many sports a slower shutter speed is actually preferable—for example, to allow the wheels of a racing automobile or motorcycle, or the rotors on a helicopter to blur realistically, as shown in Figure 6.3. At top, a 1/1,000th second shutter speed effectively stopped the rotors of the helicopter, making it look like a crash was impending. At bottom, I used a slower 1/200th second shutter speed to allow enough blur to make this a true action picture.

Figure 6.2 A shutter speed of 1/800th second was fast enough to stop this action.

Figure 6.3 A little blur can be a good thing, as these shots of a helicopter at 1/1,000th second (top) and 1/200th second (bottom) show.

But if you want to do some exotic action-freezing photography without resorting to electronic flash, the Z6’s top shutter speed is at your disposal. Here are two things to think about when exploring this type of high-speed photography:

- You’ll need a lot of light. Very high shutter speeds cut extremely fine slices of time and sharply reduce the amount of illumination that reaches your sensor. To use 1/8,000th second at an aperture of f/6.3, you’d need an ISO setting of 1600—even in full daylight. To use an f/stop smaller than f/6.3 or an ISO setting lower than 1600, you’d need more light than full daylight provides. (That’s why electronic flash units work so well for high-speed photography when used as the sole illumination; they provide both the effect of a brief shutter speed and the high levels of illumination needed.)

- High shutter speeds with electronic flash. You might be tempted to use an electronic flash with a high shutter speed. Perhaps you want to stop some action in daylight with a brief shutter speed and use electronic flash only as supplemental illumination to fill in the shadows. Unfortunately, under ordinary conditions you can’t use flash in subdued illumination with your Z6 at any shutter speed faster than 1/200th second. That’s the fastest speed at which the camera’s focal plane shutter is fully open. Shorter shutter speeds are achieved by releasing the rear curtain before the front curtain has reached the end of the frame, so the sensor is exposed by a moving slit (described in more detail in Chapter 9). The flash will expose only the small portion of the sensor exposed by the slit throughout its duration. (Check out “High-Speed Sync” in Chapter 9 if you want to see how you can use shutter speeds shorter than 1/200th, albeit at much-reduced effective flash power levels.)

Working with Short Exposures

You can have a lot of fun exploring the kinds of pictures you can take using very brief exposure times, whether you decide to take advantage of the action-stopping capabilities of your built-in or external electronic flash or work with the Nikon Z6’s faster shutter speeds. Here are a few ideas to get you started:

- Take revealing images. Fast shutter speeds can help you reveal the real subject behind the façade, by freezing constant motion to capture an enlightening moment in time. Legendary fashion/portrait photographer Philippe Halsman used leaping photos of famous people, such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Richard Nixon, and Salvador Dali to illuminate their real selves. Halsman said, “When you ask a person to jump, his attention is mostly directed toward the act of jumping and the mask falls so that the real person appears.” Try some high-speed portraits of people you know in motion to see how they appear when concentrating on something other than the portrait. Figure 6.4 provides an example.

- Create unreal images. High-speed photography can also produce photographs that show your subjects in ways that are quite unreal. A motocross cyclist leaping over a ramp, but with all motion stopped so that the rider and machine look as if they were frozen in mid-air, make for an unusual picture. When we’re accustomed to seeing subjects in motion, seeing them stopped in time can verge on the surreal.

Figure 6.4 Shoot your subjects leaping and see what they look like when they’re not preoccupied with posing.

- Capture unseen perspectives. Some things are never seen in real life, except when viewed in a stop-action photograph. MIT electronics professor Harold Edgerton’s famous 1962 photo of a bullet passing through an apple was only a starting point. Freeze a hummingbird in flight for a view of wings that never seem to stop. Or, capture the splashes as liquid falls into a bowl, as shown in Figure 6.5. No electronic flash was required for this image. Instead, two high-intensity lamps with green gels at left and right and an ISO setting of 1600 allowed the camera to capture this image at 1/2,000th second.

- Vanquish camera shake and gain new angles. Here’s an idea that’s so obvious it isn’t always explored to its fullest extent. A high enough shutter speed can free you from the tyranny of a tripod, and the somewhat limited anti-shake capabilities of image stabilization, making it easier to capture new angles, or to shoot quickly while moving around, especially with longer lenses. I tend to use a monopod or tripod frequently, and I end up missing some shots because of a reluctance to adjust my camera support to get a higher, lower, or different angle. If you have enough light and can use an f/stop wide enough to permit a high shutter speed, you’ll find a new freedom to choose your shots. I have a favored Nikon AF-S 200-500mm f/5.6E ED VR lens that I use for sports and wildlife photography, almost invariably with a tripod, as I don’t find the “reciprocal of the focal length” rule particularly helpful in most cases. I would not hand-hold this hefty lens at its 500mm setting with a 1/500th second shutter speed under most circumstances. However, at 1/2,000th second or faster, it’s entirely possible for a steady hand to use this lens without a tripod or monopod’s extra support, and I’ve found that my whole approach to shooting animals and other elusive subjects changes in high-speed mode. Selective focus allows dramatically isolating my prey wide open at f/5.6, too. Of course, at such a high shutter speed, you may need to boost your ISO setting—even when shooting outdoors.

Figure 6.5 A large amount of artificial illumination and an ISO 1600 sensitivity setting allowed capturing this shot at 1/2,000th second without use of an electronic flash.

Long Exposures

Longer exposures are a doorway into another world, showing us how even familiar scenes can look much different when photographed over periods measured in seconds. At night, long exposures produce streaks of light from moving, illuminated subjects like automobiles or amusement park rides. Extra-long exposures of seemingly pitch-dark subjects can reveal interesting views using light levels barely bright enough to see by. At any time of day, including daytime (in which case you’ll often need the help of neutral-density filters to make the long exposure practical), long exposures can cause moving objects to vanish entirely, because they don’t remain stationary long enough to register in a photograph.

Three Ways to Take Long Exposures

There are actually three common types of lengthy exposures: timed exposures, bulb exposures, and time exposures. The Z6 offers all three. Because of the length of the exposure, all of the following techniques should be used with a tripod to hold the camera steady.

- Timed exposures. These are long exposures from 1 second to 30 seconds, measured by the camera itself. To take a picture in this range, simply use Manual or S modes and use the main command dial to set the shutter speed to the length of time you want, choosing from preset speeds of 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 6.0, 8.0, 10.0, 15.0, 20.0, or 30.0 seconds (if you’ve specified 1/2-stop increments for exposure adjustments), or 1.0, 1.3, 1.6, 2.0, 2.5, 3.2, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 8.0, 10.0, 13.0, 15.0, 20.0, 25.0, and 30.0 seconds (if you’re using 1/3-stop increments). The advantage of timed exposures is that the camera does all the calculating for you. There’s no need for a stopwatch. If you review your image on the monitor and decide to try again with the exposure doubled or halved, you can dial in the correct exposure with precision. The disadvantage of timed exposures is that you can’t take a photo for longer than 30 seconds.

- Bulb exposures. This type of exposure is so-called because in the olden days the photographer squeezed and held an air bulb attached to a tube that provided the force necessary to keep the shutter open. Traditionally, a bulb exposure is one that lasts as long as the shutter release button is pressed; when you release the button, the exposure ends. To make a bulb exposure with the Z6, set the camera on Manual mode and use the main command dial to select the first shutter speed immediately after 30 seconds—Bulb. Then, press the shutter or the button on a remote control (such as the MC-DC2) to start the exposure, hold it down, and then release it to close the shutter.

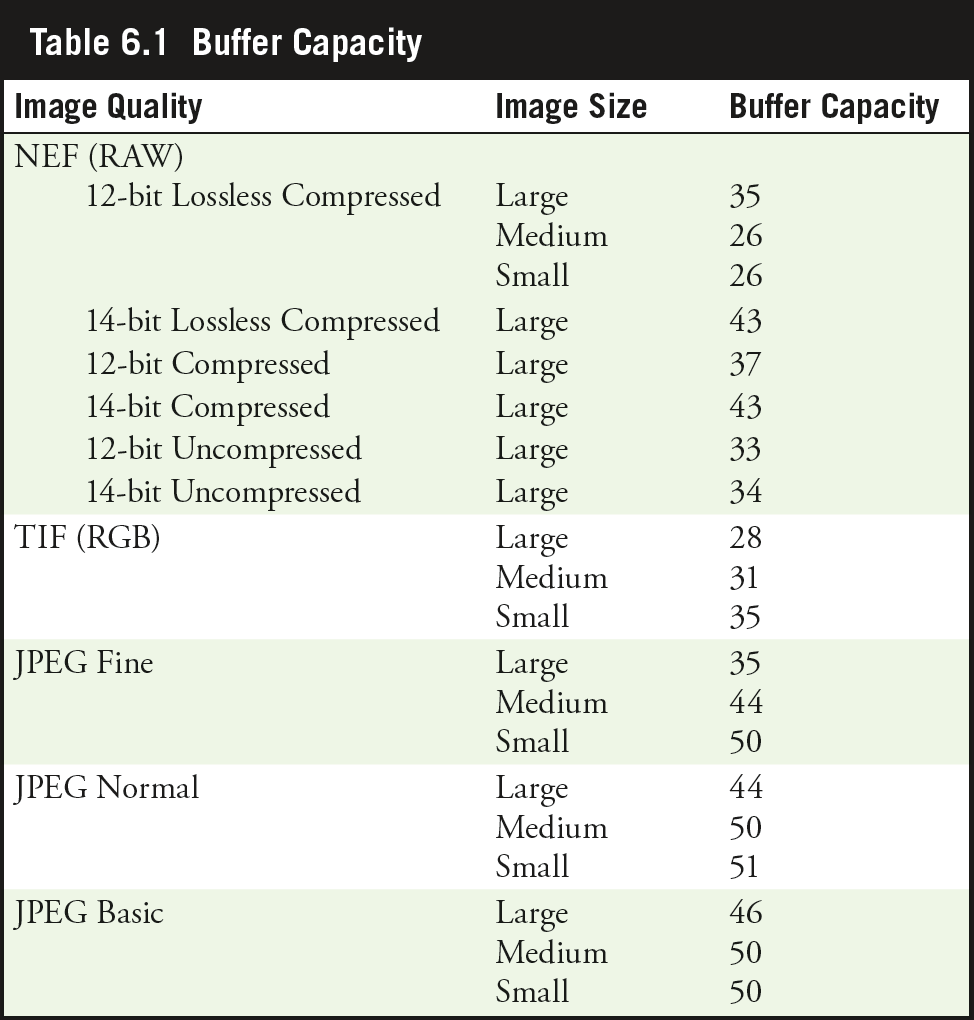

- Time exposures. On the Z6, this type of exposure is similar to Bulb, except you don’t have to hold the shutter release down. Simply press the shutter release or your remote button to start the exposure, and press a second time to stop the exposure. The setting is located just beyond Bulb when rotating the main command dial in Manual exposure mode, and is labeled Time or “- -” on the LCD monitor and top control panel, respectively. I use this instead of Bulb most of the time, especially when using the MC-DC2 release cable or making long exposures (where it would be tedious to stand there pressing a button during a Bulb exposure). You can start the exposure, go off for a few minutes, and come back to close the shutter (assuming your camera is still there). If you are not using a cable release, the advantage of using Bulb is you don’t have to touch the camera twice; just press the button and release it when finished. With shorter exposures it’s possible for the vibration of manually opening and closing the shutter to register in the photo. For longer exposures, the period of vibration is relatively brief and not usually a problem. A typical time exposure I took of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, is shown in Figure 6.6, left.

Note: If you choose Bulb or Time in Manual mode and then switch to Shutter-priority mode, the Bulb or Time setting will “stick,” but the Z6 will not take a picture in either mode. Instead, an indicator on the display and top control panel will flash, warning you to change to a usable setting. Nikon’s reasoning is that you might not realize that Bulb or Time are no longer available, and wouldn’t want the camera to choose some other setting on your behalf.

Working with Long Exposures

Because the Z6 produces such good images at longer exposures, and there are so many creative things you can do with long exposure techniques, you’ll want to do some experimenting. Get yourself a tripod or another firm support and take some test shots with long exposure noise reduction both enabled and disabled (to see whether you prefer low noise or high detail) and get started. Here are some things to try:

Figure 6.6 The Z6’s time exposure setting can give you long time exposures, such as this 60-second shot of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame (left) or this cascade in the Youghiogheny River in Pennsylvania (right).

- Show total darkness in new ways. Even on the darkest, moonless nights, there is enough starlight or glow from distant illumination sources to see by, and, if you use a long exposure, there is enough light to take a picture.

- Blur waterfalls, etc. You’ll find that waterfalls and other sources of moving liquid produce a special type of long-exposure blur, because the water merges into a fantasy-like veil that looks different at varying exposure times, and with different waterfalls. Cascades with turbulent flow produce a rougher look at a given longer exposure than falls that flow smoothly, as you can see in Figure 6.6, right. Although blurred waterfalls have become almost a cliché, there are still plenty of variations for a creative photographer to explore.

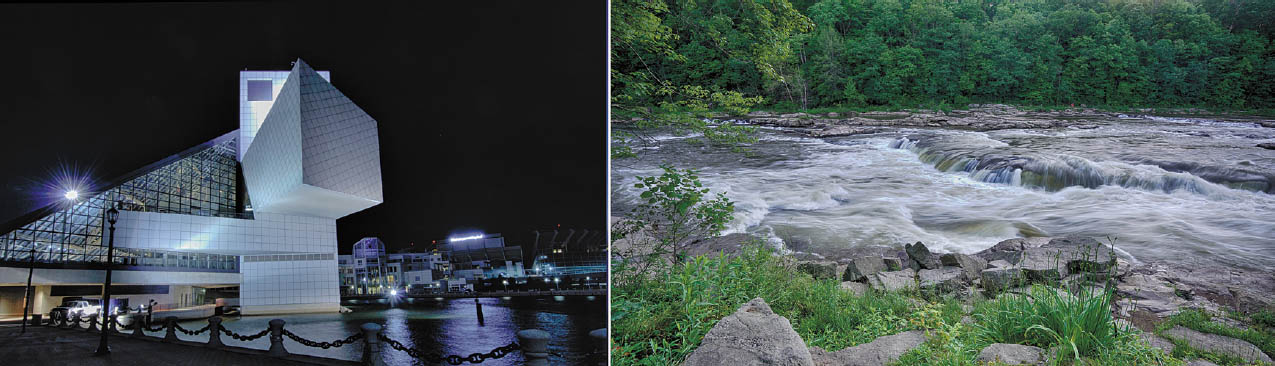

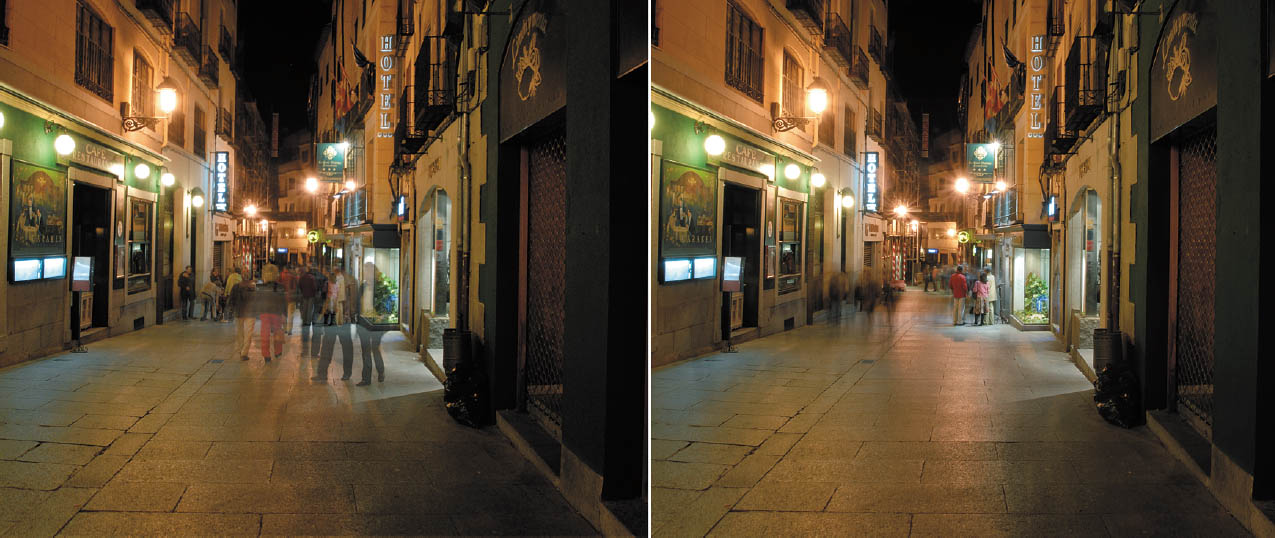

- Make people invisible. One very cool thing about long exposures is that objects that move rapidly enough won’t register at all in a photograph, while the subjects that remain stationary are portrayed in the normal way. That makes it easy to produce people-free landscape photos and architectural photos at night or, even, in full daylight if you use a neutral-density filter (or two) (or three) to allow an exposure of at least a few seconds. At ISO 100, f/22, and a pair of 8X (three-stop) neutral-density filters, you can use exposures of nearly two seconds; overcast days and/or even more neutral-density filtration would work even better if daylight people-vanishing is your goal. They’ll have to be walking very briskly and across the field of view (rather than directly toward the camera) for this to work. At night, it’s much easier to achieve this effect with the 20- to 30-second exposures that are possible, as you can see in Figure 6.7. At left, with an exposure of several seconds, the crowded street in Segovia, Spain, is fully populated. At right, with a 20-second exposure, the folks moving slowly (at left) show up as blurs; those standing still (at right) are portrayed normally; and the fast-moving walkers in the foreground are barely perceptible blurs.

Figure 6.7 This European alleyway is thronged with people (left), but with the camera on a tripod, a 20-second exposure rendered most of the passersby almost invisible.

- Create streaks. If you aren’t shooting for total invisibility, long exposures with the camera on a tripod can produce some interesting streaky effects. Even a single 8X ND filter will let you shoot at f/22 and 1/6th second in daylight. Indoors, you shouldn’t have a problem using long shutter speeds to get shots like the one shown in Figure 6.8.

- Produce light trails. At night, car headlights and taillights and other moving sources of illumination can generate interesting light trails, as shown in the image of the carnival ride in Figure 6.9. Your camera doesn’t even need to be mounted on a tripod; hand-holding the Z6 for longer exposures adds movement and patterns to your streaky trails. If you’re shooting fireworks with a tripod, a longer exposure may allow you to combine several bursts into one picture.

Figure 6.8 Long exposures can turn dancers into a swirling image.

Figure 6.9 The carnival ride’s motion produces interesting light trails.

Delayed Exposures

Sometimes it’s desirable to have a delay of some sort before a picture is actually taken. Perhaps you’d like to get in the picture yourself, and would appreciate it if the camera waited 10 seconds after you press the shutter release to actually take the picture. Maybe you want to give a tripod-mounted camera time to settle down and damp any residual vibration after the release is pressed to improve sharpness for an exposure with a relatively slow shutter speed. It’s possible you want to explore the world of time-lapse photography. The next sections present your delayed exposure options.

Self-Timer

The Z6 has a built-in self-timer with a user-selectable delay. Activate the timer by pressing the Release Mode button and rotating the main command dial to the self-timer icon. Press the shutter release button halfway to lock in focus on your subjects (if you’re taking a group shot of yourself and several others, focus on an object at a similar distance and use focus lock). When you’re ready to take the photo, continue pressing the shutter release the rest of the way. The lamp on the front of the camera will blink slowly for eight seconds (when using the 10-second timer) and the beeper will chirp (if you haven’t disabled it in the Custom Settings menu, as described in Chapter 12). During the final two seconds, the beeper sounds more rapidly and the lamp remains on until the picture is taken. It’s a good idea to close the viewfinder eyepiece shutter if you’re not using live view or shooting in Manual exposure mode, to prevent light from the viewing window getting inside the camera and affecting the automatic exposure.

You can customize the settings of the self-timer. Your adjustments are “sticky” and remain in effect until you change them. Your options include:

- Self-timer delay. Choose 2, 5, 10, or 20 seconds, using Custom Setting c2. If I have the camera mounted on a tripod or other support and am too lazy to dig around for my wired remote, I can set a two-second delay that is sufficient to let the camera stop vibrating after I’ve pressed the shutter release. A longer delay time of 20 seconds is useful if you want to get into the picture and are not sure you can make it in 10 seconds.

- Number of shots. After the timer finishes counting down, the Z6 can take from 1 to 9 different shots. This is a godsend when shooting photos of groups, especially if you want to appear in the photo itself. You’ll always want to shoot several pictures to ensure that everyone’s eyes are open and there are smiling expressions on each face. Instead of racing back and forth between the camera to trigger the self-timer multiple times, you can select the number of shots taken after a single countdown. For small groups, I always take at least as many shots as there are people in the group—plus one. That gives everybody a chance to close their eyes.

- Interval between shots. If you’ve selected 2 to 9 as your number of shots to be snapped off, you can use this option to space out the different exposures. Your choices are 0.5, 1, 2, or 3 seconds. Use a short interval when you want to capture everyone saying “Cheese!” The 3-second option is helpful if you’re using an external flash, as 3 seconds is generally long enough to allow the flash to recycle and have enough juice for the next photo.

Interval/Time-Lapse Photography

The Z6 is capable of both interval photography (for still pictures) and time-lapse video, both available from the Photo Shooting menu. The commands for both are described in Chapter 11. Who hasn’t marveled at a time-lapse photograph of a flower opening, a series of shots of the moon marching across the sky, or one of those extreme time-lapse picture sets showing something that takes a very, very long time, such as a building under construction.

You probably won’t be shooting such construction shots, unless you have a spare Z6 you don’t need for a few months (or are willing to go through the rigmarole of figuring out how to set up your camera in precisely the same position using the same lens settings to shoot a series of pictures at intervals). However, other kinds of interval and time-lapse photography are entirely within reach. If you’re willing to tether the camera to a computer (a laptop will do) using the USB cable, you can take time-lapse photos using the optional extra-cost Nikon Camera Control Pro.

For Figure 6.10, I set up my camera on a tripod and pointed it at the North Star, hoping to use Interval Timing Shooting to capture some star trails. I left the camera running for a full hour, shooting a 30-second exposure every 32 seconds. I combined the resulting pictures in Photoshop to produce the photo of the stars—with the sky’s canopy crossed by the lights from airplanes at intervals. I’ve also used interval shooting for images of sunsets. Typically, I aim the camera at the horizon and set it to shoot a three-shot bracket with a 3.0-stop increment. Then, I set the interval time to take a bracket burst every 10 seconds. Over a 10-minute span, I’ll end up with 180 images I can assemble in a variety of ways to create an interesting HDR photograph. Here are the essential tips for effective time-lapse and interval photography:

Figure 6.10 This time-lapse series captured the apparent motion of the stars as Earth rotated for a one-hour period.

- Use AC power. If you’re shooting a long sequence of stills or a lengthy time-lapse movie, consider connecting your camera to an AC adapter, as leaving the Z6 on for long periods of time will rapidly deplete the battery. To minimize power drain, set Image Review to Off in the Playback menu, and enable Silent Photography in the Interval Timer Shooting entry.

- Make sure you have enough storage space. Unless your memory card has enough capacity to hold all the images you’ll be taking, you might want to change to a higher compression rate or reduced resolution to maximize the image count.

- Make a movie. While stills shot at intervals are interesting, you can increase your fun factor by producing a time-lapse movie instead. You can also combine your interval shots into a motion picture using your favorite desktop movie-making software.

- Protect your camera. If your camera will be set up, make sure it’s protected from weather, earthquakes, animals, young children, innocent bystanders, and theft.

- Vary intervals. Experiment with different time intervals. You don’t want to take pictures too often or less often than necessary to capture the changes you hope to image.

Nikon Z6’s built-in time-lapse photography feature allows you to take pictures for up to 999 intervals in bursts of as many as nine shots, with a delay of up to 23 hours and 59 minutes between shots/bursts, and an initial start-up time of as long as 23 hours and 59 minutes from the time you activate the feature. That means that if you want to photograph a rosebud opening and would like to photograph the flower once every two minutes over the next 16 hours, you can do that easily. If you like, you can delay the first photo taken by a couple hours so you don’t have to stand there by the Z6 waiting for the right moment.

Or, you might want to photograph a particular scene every hour for 24 hours to capture, say, a landscape from sunrise to sunset to the following day’s sunrise again. I will offer two practical tips right now, in case you want to run out and try interval timer shooting immediately: use a tripod, and for best results over longer time periods, plan on connecting your Z6 to an external power source!

Movies Two Ways

Your Z6 allows you to capture time-lapse movies, rather than just a series of still pictures, in two ways. One is highly automated, while the other requires a little work on your part. I’ll explain the differences between the two, and then show you how to use either of them.

- Your camera does all the work. If you use the Z6’s Time-Lapse Movie option, which I’ll describe shortly, the camera will take all the pictures using the interval and other parameters that you specify, and then combine them to produce a movie. You can watch the video as-is, or use a video-editing program to combine it with other clips. The Time-Lapse movie entry is located in the Photo Shooting menu, and is grayed out if the photo/movie selector switch is not set to the Movie position. I describe its parameters in Chapter 11, but the process basically works much like Interval Photography, which I will detail in the following sections.

- Do-it-yourself. You gain more flexibility and some options if you capture the individual frames using the Z6’s Interval Timer, and then combine them in a video editor to produce a video. That allows you to have individual frames as stills—and at a higher resolution, too (up to the full 24 megapixels the Z6 offers)—as well as video (which is described in Chapter 11).

In fact, you aren’t limited to 1080p video, as you are when using the Time-Lapse Movie option. You can assemble the individual shots into a 4K movie, or even a faux 8K video (you’ll need a high-end monitor to display any “8K” video you produce). Nikon calls the latter 8K Time-Lapse, which it is not, because the standard frame size for 8K video is 7680 × 4320, and the Z6’s full-resolution frames measure 6048 × 4024 pixels.

Using Interval Photography

This next section will tell you everything you need to know to capture images using the Z6’s built-in intervalometer—whether you intend to use the resulting still photos as such, or plan to combine them into a home-brewed time-lapse movie. To set up interval timer shooting, just follow these steps.

Before you start:

- 1. Check your time. The Z6 uses its internal clock to activate, so make sure the time has been set accurately in the Setup menu before you begin.

- 2. Ignore release mode. You don’t need to set the camera for continuous shooting. The Z6 will take the specified number of shots at each interval regardless of release mode setting.

- 3. Set up optional bracketing. However, if you’d like to bracket exposures during interval shooting, set up bracketing prior to beginning. (You learned how to bracket in Chapter 4.) The Z6 will expose the requested number of bracketed images regardless of the number of shots per interval requested. Exposure, flash, ADL, and white balance bracketing can all be used.

- 4. Position camera. Mount the camera on a tripod or other secure support.

- 5. Fully charge the battery. You might want to connect the Z6 to the Nikon AC adapter power connector if you plan to shoot long sequences. Although the camera more or less goes to sleep between intervals, some power is drawn, and long sequences with bursts of shots can drain power even when you’re not using the interval timer feature.

- 6. Make sure the camera is protected from the elements, accidents, and theft.

When you’re ready to go, set up the Z6 for interval shooting:

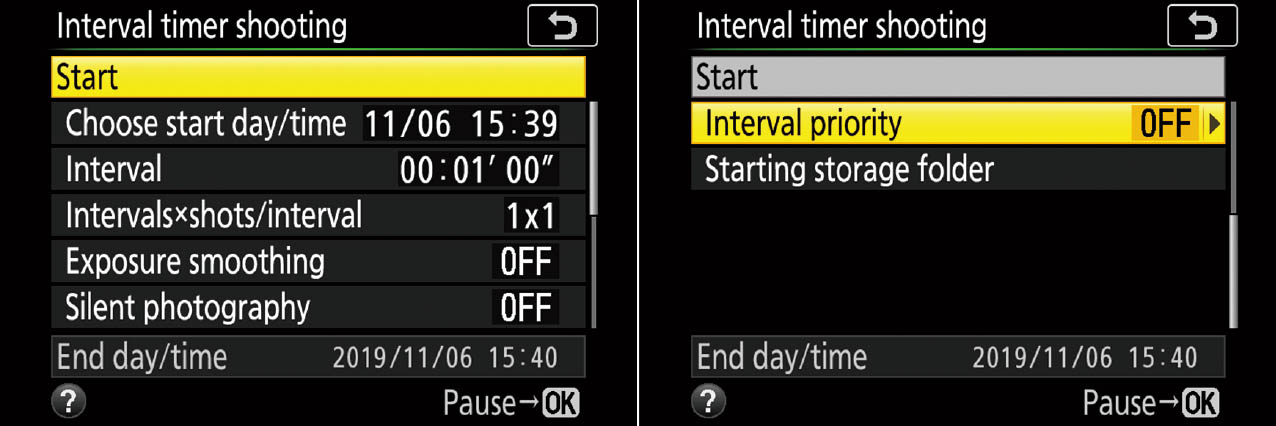

- 1. Access feature. Choose Interval Timer Shooting from the Photo Shooting menu. (See Figure 6.11, left.)

- 2. Specify a starting time. Highlight Choose Start Day/Time, and press the right directional button. A screen appears allowing you to choose either Now (to begin interval shooting immediately) or Choose Day/Time. To set a start time in the future, highlight Choose Day/Time, and press the right directional button. A screen appears that allows entering a Start Date, H (Hour), and M (Minute). You can set the current date, or up to seven days in the future. Hours are available in 24-hour format. Press OK when you’ve specified the start time. You’ll be returned to the main screen shown in Figure 6.11, left.

- 3. Set the interval between exposures. Scroll down to the Interval entry and press the right directional button. In the screen that appears, you can use the left/right buttons to move among hours, minutes, and seconds, and use the up/down buttons to choose an interval from one second to 24 hours. Press the OK button when finished to move back to the main screen.

- 4. Select the spacing and number of shots. Highlight Intervals × Shots/Interval and press the right directional button. Use the left/right buttons to highlight the number of intervals (that is, how many times you want the camera activated) and the number of shots taken after each interval has elapsed (as many as nine images taken at each activation). The total number of shots to be exposed overall will be shown at far right once you’ve entered those two parameters. You can highlight each number column separately, so that to enter, say, 250 intervals, you can set the 100s, 10s, and 1s columns individually (rather than press the up button 250 times!). You can select up to 9,999 intervals, and 9 shots per interval for a maximum of 89,991 exposures with one interval shooting cycle. Press OK to return to the main screen. Tip: Your memory card won’t hold 89,991 exposures at full resolution!

Tip

The interval cannot be shorter than the shutter speed; for example, you cannot set one second as the interval if the images will be taken at two seconds or longer.

- 5. Specify Exposure Smoothing. You can turn this feature on or off. When activated, the Z6 will adjust the exposure of each shot to match that of the previous shot in P, S, or A mode. So, if you want the shutter speed to remain the same for each image (and don’t care if the aperture is adjusted), use Shutter-priority mode. If you’d rather lock in your selected aperture (say, to keep the same depth-of-field), use Aperture-priority mode. Smoothing can also be used in Manual mode, but, of course, the Z6 won’t vary either the shutter speed or aperture. You must have set ISO Sensitivity to Auto, to allow the camera to conform exposures by adjusting the ISO instead. Press OK to confirm.

- 6. Activate Silent Shooting (if desired). You can choose On or Off for this parameter. When Silent Shooting is activated, the shutter will be silenced. This option comes in handy when you don’t want your interval photography to disturb those who might be present, or you don’t want them to know that you’re shooting entirely.

- 7. Set Interval Priority. Scroll down the screen to reveal additional choices shown in Figure 6.11, right. Interval Priority can be set to On or Off. This parameter handles situations in which the shutter speed automatically selected in Program or Aperture-priority ends up being longer than the interval between shots. Perhaps you’re shooting outdoors and daylight has waned into night and a shutter speed of, say, 2 seconds is required even though your selected interval is one second.

- Interval Priority On: The Z6 takes the picture at the specified interval anyway, even though the image may be taken at a shorter shutter speed and, therefore underexposed. You can avoid the underexposure by activating Auto ISO Sensitivity, and selecting a minimum shutter speed that is shorter than the interval time. In that case, the Z6 will increase the ISO setting (if necessary) to produce the correct exposure using the automatically selected shutter speed.

- Interval Priority Off: The chosen interval is lengthened to allow a correct exposure.

- 8. Starting Storage Folder. Highlight New Folder and press the right button to tell the Z6 to create a new folder for each time-lapse sequence. This allows you to easily keep your sequences separate in their own folders. If you’ve chosen New Folder, you can also activate Reset File Numbering, which resets the numbering of each sequence to 0001 when a new folder is created. It’s handy to have each sequence numbered separately.

Figure 6.11 Interval timer shooting options.

- 9. Activate shooting. When all the parameters have been entered, scroll to the Start option at the top of the menu and press OK. If you’ve selected Now under Start Options, then interval shooting will begin immediately. If you chose a specific date/time instead, the appropriate delay will elapse before recording begins. Leave your camera turned on (and connected to an external power source if necessary). Once you activate interval shooting, immediately before the next shooting interval begins, the shutter speed display shows the number of intervals remaining and the aperture display shows the number of shots remaining in the current interval. Between intervals, you can view that information by pressing the shutter release button halfway; when you release the button, the data appears until the standby timer expires.

PAUSE OR CANCEL INTERVAL SHOOTING

While interval shooting is underway, you can review the images already taken using the Playback button. The monitor will clear automatically about four seconds before the next interval begins. Press the OK button between intervals (but not when images are still being recorded to the memory card) or choose the Interval Timer Shooting menu entry, and select Pause. Interval shooting can also be paused by turning the camera on or off. To resume the Interval Timer Shooting menu again, press the multi selector left button, and choose Restart. You may also select Off to stop the shooting entirely.

Time-Lapse Movies

If you’ve mastered Interval Photography, shooting Time-Lapse movies to allow the Z6 to capture the individual frames and assemble them into a movie for you is a snap! The settings screen is similar to the one for interval shooting, with some additional options. The key entries include:

- Start. Unlike the similar Interval Timer found in the Photo Shooting menu, Time-Lapse Photography has no Start Options. Make your other settings, select Start, and time-lapse photography will begin automatically about three seconds later. Be sure to double-check your settings before triggering the camera.

- Interval. Select an interval between frames; use a longer value for slow-moving action, such as a flower bud unfolding. You might want to experiment and choose a time between shots of one minute or longer. Some blooms mature faster than others. Use a shorter value for movies, say, depicting humans moving around at a comical pace for a Charlie Chaplin–like effect. This parameter can be set from one second to 10 minutes.

- Shooting time. You can specify time-lapse movie duration. The longest movie you can create is a total of 7 hours, 59 minutes. That should be plenty for most applications. Andy Warhol’s 1963 flick Sleep was only 5 hours, 20 minutes long!

- Exposure smoothing. You can turn exposure smoothing on or off. When activated, the camera adjusts the exposure of each frame to match that of the previous frame in P, S, or A mode. That avoids sudden changes in exposure modes other than Manual exposure (which, of course, will remain at your manual settings throughout). Smoothing can also be used in Manual mode, but, of course, the Z6 won’t vary either the shutter speed or aperture. You must have set ISO Sensitivity to Auto to allow the Z6 to compensate appropriately for changes in brightness. Press OK to confirm.

- Silent photography. Silences the shutter sound for unobtrusive or stealth video capture.

- Image area. You must scroll down to view this option, and those that follow. You can select FX-based movie format or DX-based movie format, which I’ll explain in detail in Chapter 15. You can also turn Auto DX crop on or off, so the Z6 will recognize DX lenses and crop appropriately.

- Frame size/frame rate. Here you can select the frame size and frames per second setting for your time-lapse movie. You can choose from 4K, 3840 × 2160 30/15/24p; full HD, 1920 × 1060 60/50/30p (in both High Quality and Normal modes, also explained in Chapter 15); and standard HD, 1280 × 720 60/50p formats.

- Interval priority. This setting is similar to its intervalometer counterpart, as explained previously. It takes care of situations in which the shutter speed automatically selected in Program or Aperture-priority ends up being longer than the interval between shots. When enabled, the Z6 captures the movie frame at the specified interval, even though the image may be taken at a shorter shutter speed and underexposed.

To compensate, activate Auto ISO Sensitivity, and select a minimum shutter speed that is shorter than the interval time. The Z6 will boost ISO to allow exposure at the correct interval. When disabled, the camera increases the interval you specified to allow correct exposure. However, with some subjects, the increased time may be visible in the finished movie as a jump or delay.

Multiple Exposures

Some of my very first images captured when I was a budding photographer at age 11 were double exposures. Some were unintentional, as my box camera, using 620-size film, could take several pictures on one frame if you forgot to wind it between shots. But my initial foray into special effects as a pre-teen were shots of my brother throwing a baseball to himself, serving as both pitcher and batter thanks to a multiple exposure.

The Z6’s multiple exposure feature is remarkably flexible. It allows you to combine two to ten exposures into one image without the need for an image editor like Photoshop, and it can be an entertaining way to return to those thrilling days of yesteryear, when complex photos were created in the camera itself. In truth, prior to the digital age, multiple exposures were a cool, groovy, far-out, hep/hip, phat, sick, fabulous way of producing composite images. Today, it’s more common to take the lazy way out, snap two or more pictures, and then assemble them in an image editor like Photoshop, or use the Z6’s Image Overlay feature in the Retouch menu.

However, if you’re willing to spend the time planning a multiple exposure (or are open to some happy accidents), there is a lot to recommend the multiple exposure capability that Nikon has bestowed on the Z6. For one thing, the camera is able to combine two to ten images using the RAW data from the sensor, producing photos that are blended together more smoothly than is likely for anyone who’s not a Photoshop guru. To take your own multiple exposures, just follow these steps (although it’s probably a good idea to do a little planning and maybe even some sketching on paper first, if that’s possible):

- 1. Activate the feature. Choose Multiple Exposure from the Photo Shooting menu.

- 2. Choose Multiple Exposure mode. Select Multiple Exposure mode. A submenu appears with three choices:

- On (series). The Multiple Exposure feature remains active even after you’ve taken a complete set of exposures for the number of shots you specified. Use this if you want to shoot several multiple exposures in a row. Remember to turn it off when you’re done.

- On (single photo). Once you’ve taken a single set of multiple exposures, the feature turns itself off.

- Off. Use this option to cancel multiple exposures.

- 3. Choose exposures per frame. Select Number of Shots, choose a value from 2 to 10 with the multi selector up/down buttons, and press OK.

- 4. Specify ratio of exposure between frames. Choose Overlay Mode and select Add, Average, Lighten, or Darken.

- Add. Each new exposure is added to the previous shots, with each individual image fully exposed and overlaid on the others in the frame. Use when photographing a subject that is moving against a dark background, to track movement.

- Average. The overall exposure is divided by the number of shots in the series, and each image is allocated that fraction of the overall exposure. Use this when shooting subjects with a great deal of overlap.

- Lighten. The camera compares pixels in the same position in each exposure, and uses only the brightest. This effect is similar to the Lighten blending mode in Photoshop, Lightroom, and other image-editing software. Use this to allow the lightest tones of each shot in the series to show through, such as multiple bursts in a fireworks show. The sky will remain dark, but the pyrotechnics will be captured perfectly. You may have to experiment with this setting until you become familiar with what it does to your images.

- Darken. Similar to the Lighten blending mode, only just the darkest pixel is saved. You’d use this in situations that are the opposite of those typical of the Add selection. That is, if the background is light, and a darker subject is moving across that background, Darken would provide separate images.

- 5. Confirm gain setting. Press OK to set the gain.

- 6. Keep all exposures? Ordinarily, the Z6 combines all the shots into a single exposure. However, you can ask the camera to save all the individual images in the series by choosing On in the Keep All Exposures entry.

- 7. Shoot your multiple exposure set. Take the photo by pressing the shutter release button multiple times until all the exposures in the series have been taken. (In continuous shooting mode, the entire series will be shot in a single burst.) The blinking multiple exposure icon vanishes when the series is finished. Reminder: you’ll need to deactivate the Multiple Exposure feature once you’ve finished taking a set in On (series) mode, as the setting remains even after the camera has been powered off.

Keep in mind if you wait longer than 30 seconds between any two photos in the series, the sequence will terminate and combine the images taken so far. If you want a longer elapsed time between exposures, go to the Playback menu and make sure On has been specified for Image Review, and then extend the Standby Timer using Custom Setting c3: Power Off Delay to an appropriate maximum interval. The camera will grant you an additional 30 seconds beyond that. The Multiple Exposure feature will then use the monitor-off delay as its maximum interval between shots. To capture Ana Popović, the world’s best Serbian blues guitarist, for Figure 6.12, I used a three-shot multiple exposure.

Figure 6.12 The Z6’s Multiple Exposure capability allows combining images without an image editor.

Geotagging with the Nikon GP-1a

A swarm of satellites in geosynchronous orbits above Earth became a big part of my life even before I purchased the Nikon Z6. I use the GPS features of my iPhone Xs Max and iPad Air and the GPS device in my car to track and plan my movements. When family members travel without me—most recently to Europe—I can use the Find my iPhone feature to see where they are roaming and vicariously accompany them with Google Maps’ Street View features. And, since the introduction of the Nikon GP-1a accessory, GPS has become an integral part of my shooting regimen, too.

The GP-1a unit makes it easy to tag your images with the same kind of longitude, latitude, altitude, and time stamp information that is supplied by the GPS unit you use in your car. (Don’t have a GPS? Photographers who get lost in the boonies as easily as I do must have one of these!) The geotagging information is stored in the metadata space within your image files, and can be accessed by Nikon NX-i, or by online photo services such as mypicturetown.com and Flickr.

Geotagging can also be done by attaching geographic information to the photo after it’s already been taken. This is often done with online sharing services, such as Flickr, which allow you to associate your uploaded photographs with a map, city, street address, or postal code. When properly geotagged and uploaded to sites like Flickr, users can browse through your photos using a map, finding pictures you’ve taken in a given area, or even searching through photos taken at the same location by other users. Of course, in this day and age it’s probably wise not to include GPS information in photos of your home, especially if your photos can be viewed by an unrestricted audience.

Having this information available makes it easier to track where your pictures are taken. That can be essential, as I learned from a trip out west, where I found the red rocks, canyons, and arroyos of Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and Colorado all pretty much look alike to my untrained eye. I find the capability especially useful when I want to return to a spot I’ve photographed in the past and am not sure how to get there. I can enter the coordinates shown into my hand-held or auto GPS (or an app in my iPad or iPhone) and receive instructions on how to get there. That’s handy if you’re returning to a spot later in the same day, or months later.

Like all GPS units, the Nikon GP-1a obtains its data by triangulating signals from satellites orbiting Earth. It works with the Nikon Z6, as well as many other Nikon cameras. At about $312, it’s not cheap, but those who need geotagging—especially for professional mapping or location applications—will find it to be a bargain.

The GP-1a (see Figure 6.13, left) slips onto the accessory shoe on top of the Nikon Z6. It connects to the remote/accessory port on the camera using the Nikon GP1-CA90 cable, which plugs into the connector marked CAMERA on the GP-1a.

Figure 6.13 Nikon GP-1a geotagging unit (left). Captured GPS information can be displayed when you review the image (right).

EXTRA REMOTE

The GP-1a has a port labeled with a remote-control icon, so you can plug in the Nikon MC-DC2 remote release, and it will work just fine, even when the GPS accessory is attached.

A third connector connects the GP-1a to your computer using a USB cable. Nikon has released a utility for Windows and Mac operating systems that allows you to read GPS data from the GP-1a directly in your computer—no camera required. I tried the driver, and discovered that the GP-1a couldn’t “see” any satellites from inside my office (big surprise). I plan on trying it with my netbook outdoors, in a car, or in some other more satellite-accessible location. Once attached, the device is very easy to use. You need to activate the Nikon Z6’s GPS capabilities in the GPS choice within the Setup menu, as described in Chapter 13.

The first step is to allow the GP-1a to acquire signals from at least three satellites. If you’ve used a GPS in your car, you’ll know that satellite acquisition works best outdoors under a clear sky and out of the “shadow” of tall buildings, and the Nikon unit is no exception. It takes about 40 to 60 seconds for the GP-1a to “connect.” A red blinking LED means that GPS data is not being recorded; a green blinking LED signifies that the unit has acquired three satellites and is recording data. When the LED is solid green, the unit has connected to four or more satellites, and is recording data with optimum accuracy.

Next, set up the camera by selecting the GPS option found under Location Data in the Setup menu on the Nikon Z6. There are four choices:

- Download From Smart Device. This setting allows you to download GPS/location data collected by your smart device, and then embed that information in the EXIF metadata within the image file. Choose Yes, and the data will be included when you are not using a GPS device while the two are connected for a period of up to two hours while the camera is powered up and the standby timer has not expired. If the GPS unit is connected, its location data will be used instead when both the GPS and smart device are in play.

- Standby Timer. Setting to Enable reduces battery drain by enabling turning off exposure meters while using the GP-1/1a after the time specified for the Standby Timer in Custom Setting c3: Power Off Delay (discussed in Chapter 12) has elapsed. When the meters turn off, the GP-1/1a becomes inactive and must reacquire at least three satellite signals before it can begin recording GPS data once more. Setting to Disable causes exposure meters to remain on while using the GP-1/1a, so that GPS data can be recorded at any time, despite increased battery drain.

- Position. This is an information display, rather than a selectable option. It appears when the GP-1/1a is connected and receiving satellite positioning data. It shows the latitude, longitude, altitude, and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) values.

- Set Clock From Satellite. Choose Yes to allow the camera to update its internal clock from information provided by the GPS device when attached. Choosing No disables this updating feature. You might want to avoid updating the clock if you’re traveling and want all the basic date/time information embedded in your image files to reflect the settings back home, rather than the date and time where your pictures are taken. Note that if the GPS device is active when shooting, the local date and time will be embedded in the GPS portion of the EXIF data.

Once the unit is up and running, you can view GPS information using photo information screens available on the color monitor (and described in Chapter 2). The GPS screen, which appears only when a photo has been taken using the GPS unit, looks something like Figure 6.13, right.

Focus Shift Shooting

If you are doing macro (close-up) photography of flowers, or other small objects at short distances, the depth-of-field often will be extremely narrow. In some cases, it will be so narrow that it will be impossible to keep the entire subject in focus in one photograph. Although having part of the image out of focus can be a pleasing effect for a portrait of a person, it is likely to be a hindrance when you are trying to make an accurate photographic record of a flower, or small piece of precision equipment. One solution to this problem is focus stacking (which Nikon calls “Focus Shift Shooting”), a procedure that can be considered like HDR translated for the world of focus—taking multiple shots with different settings, and, using software as explained below, combining the best parts from each image in order to make a whole that is better than the sum of the parts. Focus stacking requires a non-moving object, so some subjects, such as flowers, are best photographed in a breezeless environment, such as indoors.

With the Z6’s Focus Shift Shooting feature, the camera takes a series of pictures, adjusting the focus slightly between each image, refocusing from closest to your subject to the farthest point that needs to appear sharp. You end up with a series of up to 300 different images that can be combined using two simple Photoshop commands, which I will describe shortly.

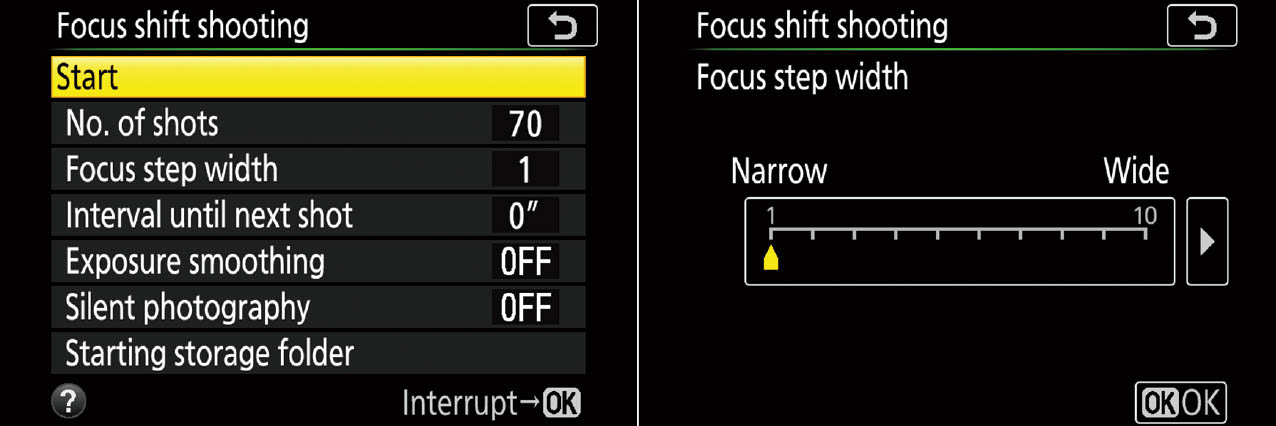

You can visualize how focus stacking works if you examine Figure 6.14, which is cropped versions of three actual frames from one of my own focus shift series. All three used an exposure of 1/30th second at f/4 with my 50mm f/1.8 Nikkor-S. At top is the original exposure, with the lens focused on the closest die. The center image shows the 35th exposure in the series, in which the focus shift feature had adjusted focus on the red die in the back. In between were 33 intermediate-focus shots that I merged in Photoshop to produce the finished image at bottom. Here are the detailed steps you can take to use Focus Shift shooting for your own deep-focus images:

Figure 6.14 Closest focus (top), farthest focus (center), merged image (bottom).

- 1. Set the camera firmly on a solid tripod. A tripod or other equally firm support is absolutely essential for this procedure. You don’t want the camera (or the subject) to move at all during the exposures.

- 2. Attach a remote release, such as the MC-DC2. You want to be able to trigger the camera without moving it. However, the procedure does pause for a short period of time once you activate it, perhaps giving your tripod/camera time to settle down.

- 3. Attach a lens with an appropriate focus range. Focus Shift uses the lens’s built-in autofocus motor, so you cannot use a manual focus lens or one that does not have an internal autofocus motor.

- 4. Set the focus modes. Activate AF-S (single focus) as your focus mode and Single-Point AF as your AF-area mode. The lens switch must be set to Autofocus.

- 5. Set the quality of the images to JPEG FINE *. Use the Photo Shooting menu to make this adjustment.

- 6. Set the exposure, ISO, and white balance manually. Use test shots if necessary to determine the best values. This step in the Photo Shooting menu will help prevent visible variations from arising among the multiple shots that you’ll be taking. You don’t want the camera to change the exposure, ISO setting, or white balance between shots.

Note: Even though you’ll be effectively increasing depth-of-field through focus stacking, you should still avoid the widest apertures of your lens, as they are rarely the sharpest f/stops. I always stop down at least 1.5 f/stops—using f/4 in the example. Shutter speed is not as important, because the camera is on a tripod, but I tend to avoid very slow speeds anyway. You can manually set a slightly higher ISO sensitivity, if needed, to obtain the shutter speed/aperture combination you want to use.

- 7. Turn off image stabilization. Disable Vibration Reduction in the Photo Shooting menu. If your FTZ-adapted lens has VR, slide the VR switch to Off.

- 8. Set focus point to nearest object. Use the directional buttons to position the red focus box on the subject nearest the camera lens.

- 9. Access the Focus Shift Shooting menu. You’ll find it near the end of the Photo Shooting menu, and shown at left in Figure 6.15.

Figure 6.15 Focus Shift Shooting options.

Select an appropriate setting for each of the following six parameters, using my guidelines:

- No. of Shots. You can choose from 1 to 300 individually refocused shots. The number of images captured will depend on how finely you want to have the Z6 change focus between shots (and you’ll combine this with the step width option described next). I rarely need more than 50 shots, and used only 35 for the example shown earlier in Figure 6.14.

- Focus Step Width. You can specify values from 1 (a narrow slice per adjustment) and 10 (a much wider focus change). Nikon does not specify how much each increment changes the focus, for a very good reason: it can’t. Depending on the focal length of your lens and your f/stop, the effective plane of apparent focus may vary from narrow, to very narrow, to supernarrow in macro shooting environments. (If you’re confused, see “Circles of Confusion” in Chapter 5.)

You may need some trial-and-error to choose the correct number of shots and focus step width. For example, with 50 shots and a wide focus step, the first 10 may encompass your entire subject and the last 40 may be wasted on completely out-of-focus images. It’s often worthwhile to take a test shot, view a slide show of all your images, and decide whether to increase/decrease the number of shots and/or focus step width.

- Interval Until Next Shot. You can select 00 seconds to 30 seconds. At 00 seconds, the Z6 will take all the photos consecutively at a rate of 5 frames per second in Single Shot, or either Continuous mode. The 00-second setting works well when shooting by ambient light that doesn’t change. However, you can use flash, too. Just specify an interval that is greater than the maximum recycle rate of your flash.

- Exposure Smoothing. I recommend shooting under a steady, constant source of illumination and using Manual exposure. However, if you’re working outdoors that may not be possible. In that case, in semi-automatic modes turn Exposure Smoothing On and allow the Z6 to match exposure between frames. Exposure Smoothing works in Manual exposure mode, too, if you enable Auto ISO Sensitivity so the camera can change ISO sensitivity during your sequence if required.

- Silent Photography. You can capture your images silently using the electronic shutter if you activate this option. I prefer to hear the comforting click as my camera captures its sequence, but if you’re in stealth or “do not disturb” modes, silent photography is available.

- Starting Storage Folder. Choose New Folder, and each time you shoot a sequence, the Z6 will create a fresh folder. I can’t think of a reason you would not want to do that. Select Reset File Numbering, and the file numbering is reset each time a new folder is created, which makes it easier to differentiate between the first, last, and in-between images of your set.

- 10. Capture images. When all the parameters are locked in, highlight Start and press the OK button. The LCD monitor displays a “Preparing . . .” message and then commences the capture within a second or two. Note that Focus Shift is not “sticky.” Once you’ve grabbed a sequence, the feature is turned off and you must Start again to repeat, or change parameters and Start anew.

- 11. Combine your images. I’ll describe the steps for that next.

The next step is to process the images you’ve taken in Photoshop. Transfer the images to your computer, and then follow these steps:

- 1. In Photoshop, select File > Scripts > Load Files into Stack. In the dialog box that then appears, navigate on your computer to find the files for the photographs you have taken, and highlight them all.

- 2. At the bottom of the next dialog box that appears, check the box that says, “Attempt to Automatically Align Source Images,” then click OK. The images will load; it may take several minutes for the program to load the images and attempt to arrange them into layers that are aligned based on their content.

- 3. Once the program has finished processing the images, go to the Layers panel and select all of the layers. You can do this by clicking on the top layer and then Shift-clicking on the bottom one.

- 4. While the layers are all selected, in Photoshop go to Edit > Auto-Blend Layers. In the dialog box that appears, select the two options, Stack Images and Seamless Tones and Colors, then click OK. The program will process the images, possibly for a considerable length of time.

- 5. If the procedure worked well, the result will be a single image made up of numerous layers that have been processed to produce a sharply focused rendering of your subject. If it did not work well, you may have to take additional images the next time, focusing very carefully on small slices of the subject as you move progressively farther away from the lens.

- 6. You’ll want to flatten the final image before saving it. Given the 24 MP resolution of the Z6, the stack of individual shots will easily be more than 2GB, which exceeds the maximum file size of some storage media and/or OS file systems.

Although this procedure can work very well in Photoshop, you also may want to try it with programs that were developed more specifically for focus stacking and related procedures, such as Helicon Focus (www.heliconsoft.com), PhotoAcute (www.photoacute.com), or CombineZP (https://alan-hadley.software.informer.com/).

Trap (Auto) Focus

Trap focus comes in handy when you know where the action is going to take place (such as at the finish line of a horse race), but you don’t know exactly when. The solution is to prefocus on the point where the action will occur, and then tell your camera not to actually take the photo until something moves into the prefocus spot (see Figure 6.16). It’s a good technique for sports action when you know that, say, a runner is going to pass by a certain position. You can also use trap focus for hand-held macro shots—set focus for a particular distance and then move the camera toward your subject. The shutter will trip automatically when your subject comes into focus.

Figure 6.16 By prefocusing on the area between two hurdles, trap focus captured the center athlete the instant he moved into the point of focus.

Trap focus isn’t as difficult as you might think. The key is to decouple the focusing operation from the shutter release function, just as you do with back button focus. Just follow these steps:

- 1. Confirm AF-ON button. First, access Custom Setting f2 and make sure the definition for the AF-ON button is set to its default value, AF-ON, and not some other behavior. You want the AF-ON button to activate autofocus.

- 2. Disable Out-of-Focus Release. Navigate to Custom Setting a7: AF Activation. Highlight AF-ON Only, press the right button, and set Out-of-Focus Release to Disable. Then, pressing the shutter release halfway down does not activate autofocus. That happens only when you press the AF-ON button.

- 3. Set Custom Setting a2 to Focus Priority. Because you’ve just disabled Out-of-Focus Release (above), henceforth the shutter will trip only when your subject is in focus.

- 4. Set focus mode to AF-S. Press the Fn2 button and rotate the main command dial to select Single Focus.

- 5. Set your point selection mode to Single-point AF. Press the Fn2 button and rotate the sub-command dial to select the Single-point AF-area mode.

- 6. Make sure your lens is set to autofocus (either A or M/A). Duh! And yet some people forget this step.

- 7. Prefocus on the spot where the action will occur, or an equivalent distance. I like to manually focus on that point to make sure it is the exact position I want to capture. For Figure 6.16, I focused on a plane between the third and fourth hurdles, which were located 30 feet apart (the standard for men’s hurdle events). You can also press the AF-ON button to focus on that point, and then release the button. In either case, further AF activity will cease. The prefocused distance is the “trap” you’ve set for your pending subject.

- 8. Reframe your picture, if necessary, so that nothing is at the prefocused distance. (If an object occupies that spot, the camera will take the photo immediately when you press the shutter release.)

- 9. Press and hold down the shutter release all the way. The camera will not refocus, because you’ve disconnected the autofocus function from the shutter release. Nor will it take a picture, because Focus-priority has been set. You can now reframe your image to the point where the action will take place.

- 10. Trap sprung! The picture will be taken when a subject moves into the prefocused area. Note that trap focus may not work well with some subjects, particularly when using small f/stops. Increased depth-of-field may cause the Z6 to take the photo when your subject has barely entered the trap and not yet perfectly in the preselected focus plane. Even so, trap focus is a very useful technique.

If you don’t use trap focus often, or don’t work with the AF-ON button as your primary autofocus start control regularly, don’t make the mistake I did. One time I forgot that I had followed the steps above, and used a different camera in the interim. The next time I picked up my Z6, it “refused” to autofocus—at least when I pressed the shutter release halfway. Much consternation followed until I remembered what I had done a few days earlier, pressed the AF-ON button, and found that the AF function was just fine. I had simply “turned off” the shutter release as an AF start control. While in olden times it was common to keep a settings log, the Z6 has a simpler way of heading off this problem. Just dedicate a User Setting to the parameters I describe above for trap focus. Then spin the mode dial to that position (U1, U2, or U3) when you want to use trap focus, and switch to a different position on the dial to return to your previous settings. I’ll show you how to save User Settings in Chapter 13.

Using SnapBridge

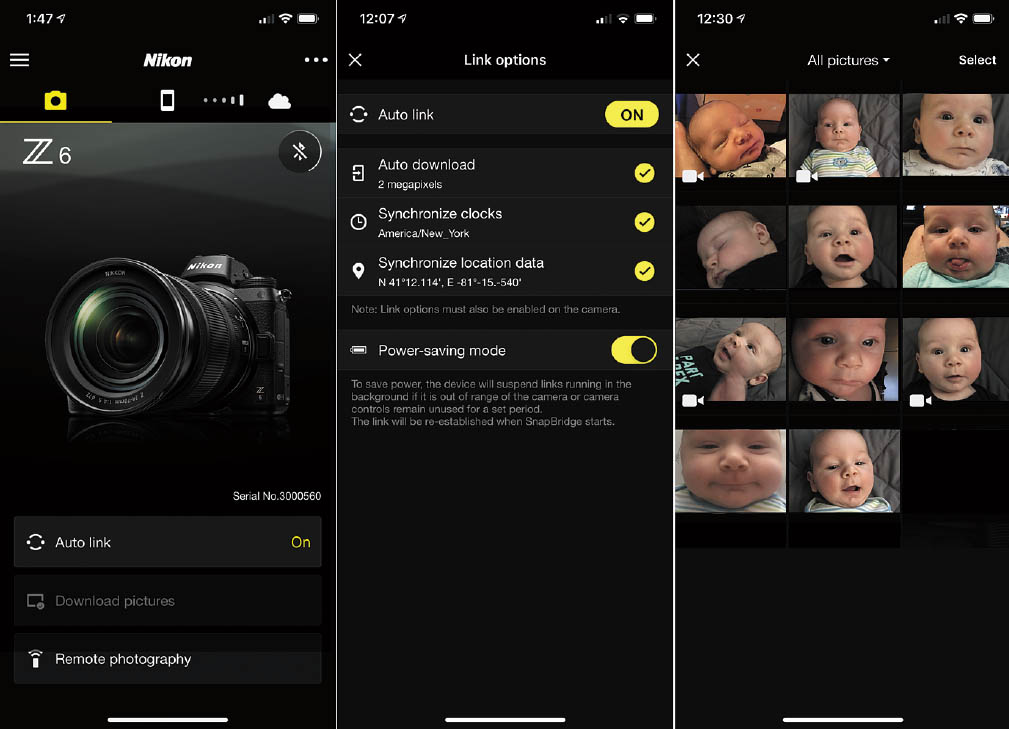

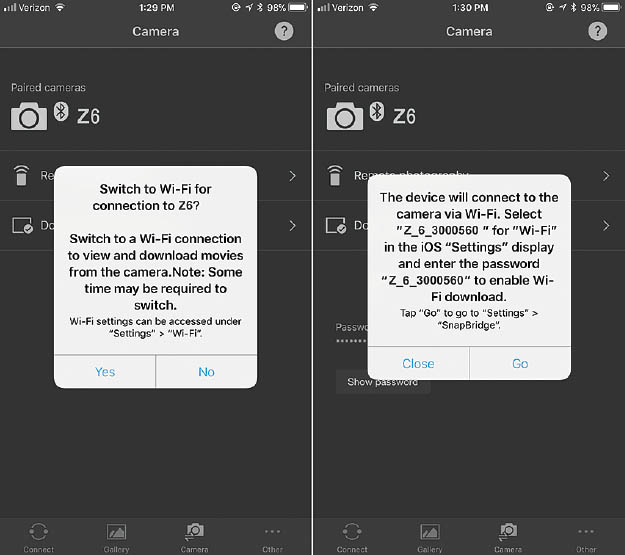

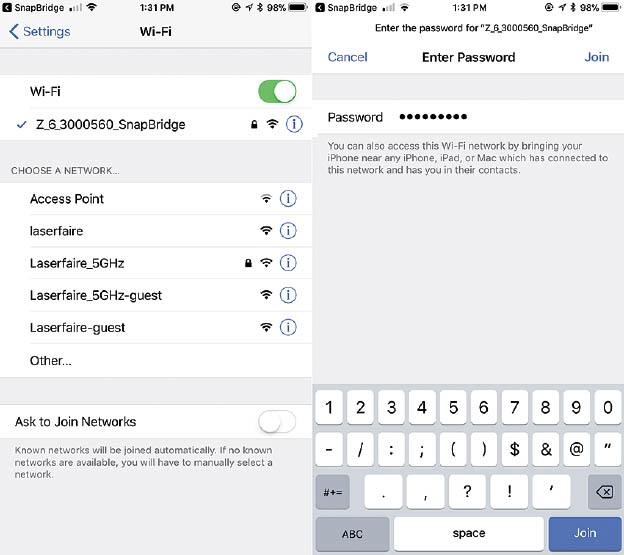

Nikon has elected to blaze a trail of its own in implementing wireless connectivity on the Z6, using a new system it calls SnapBridge. It features both Bluetooth LE (Low Energy) and Wi-Fi connections. You can connect to your computer over Wi-Fi, or to your smart device running the SnapBridge app using either Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. Bluetooth can safely be left active at all times, because it provides little drain on the Z6’s battery when not being actively used. That makes connecting camera and smart device much quicker. A Wi-Fi connection, using the Z6’s built-in Wi-Fi access point, is the required choice for movies and a good idea for transferring large numbers of images in one session.

WI-FI COMPUTER CONNECTIONS

Unless you have LAN or IT experience, all the options available (and explained in Nikon’s lengthy 60-page Network Guide) probably will have your eyes glazing over. Indeed, Page X of the guide says it “assumes basic knowledge of wireless LANs.” Wait, what?

You can link the Z6 to your computer using the camera’s built-in wireless local area network by access-point mode, by infrastructure mode using a wireless router, or using Nikon’s optional, but very pricey (about $750) WT-7a transmitter. The latter has both wireless and Ethernet connections and can upload photos and movies to a computer, your smart device, or FTP server, plus control the Z6 remotely using the optional Camera Control 2 software, or view/capture pictures (but not movies) wirelessly with a browser on your computer or smart device.

All this is beyond the scope of this book, even if there were room for a 60-page chapter that deals with computer technology rather than photography. Instead, I’m going to provide you with an introduction to SnapBridge that should get you up and running, and urge you to download the Network Guide PDF from your country’s Nikon website, and use that if you need more help.

Here’s some of what you can do with SnapBridge:

- Auto uploads. You can use SnapBridge to automatically upload JPEG images (but not RAW files) from your camera to your smart device.

- Upload selected photos. During image review (Playback mode), you can press the i button and choose Select to Send to Smart Device/Deselect to choose specific images to transfer to your smart device. You can also use the Select to Send to Smart Device entry in the Playback menu. Up to 1,000 photos can be marked for upload in one session.

- Resize images. Obviously uploading full-resolution images to your smart device would be slow and use a lot of storage space on your device. SnapBridge defaults to low-resolution 2-megapixel images (which should be fine for smart device display or sharing on social media), and the app lets you specify a different upload size.

- Add credits. The app also lets you choose to embed comments and copyright information entered in the Setup menu (as described in Chapter 13) or entered using the SnapBridge app itself.

- Multiple devices. If you own multiple phones and tablets, you can pair the camera with as many as five different devices. However, the Z6 can connect to only one at a time. You can manually switch between devices using the connection options described shortly.

- Remote control. You can trigger the shutter using your smart device (as long as the camera is on), giving you wireless remote control without the need of purchasing an accessory.

- Imprint photos. You can overlay comments or the time the photo was taken.

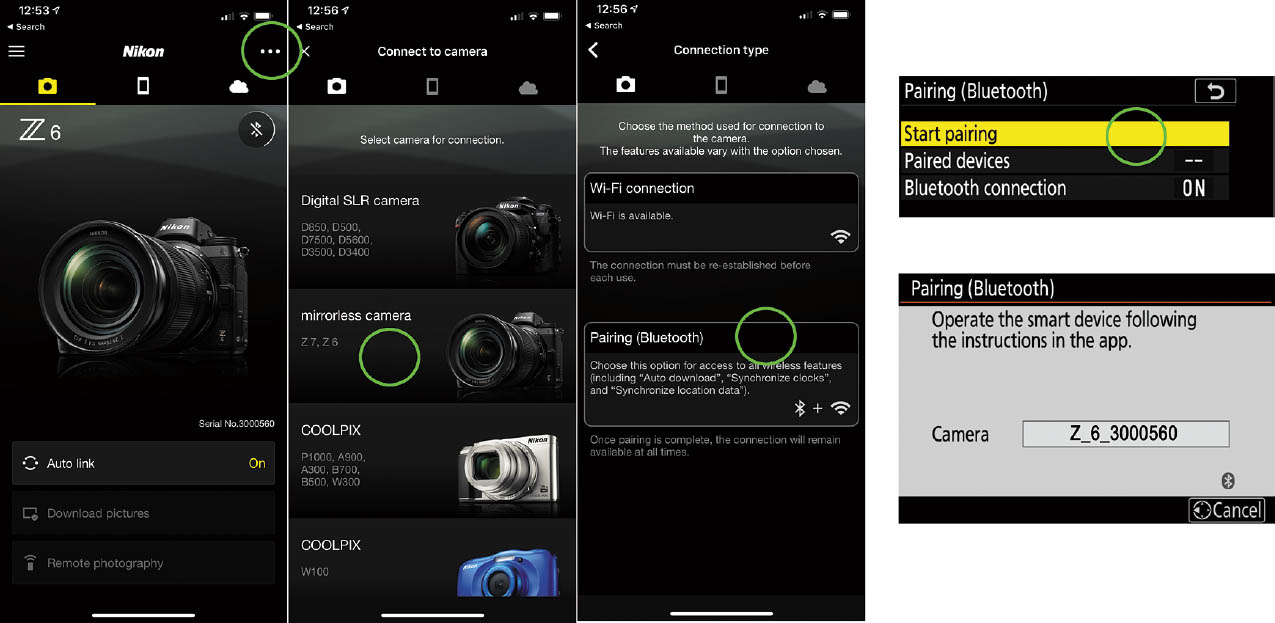

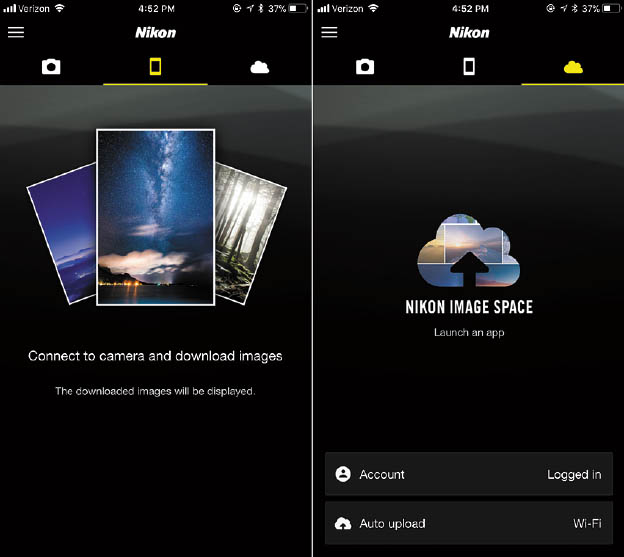

As I noted earlier, the Z6’s SnapBridge app supports camera-to-smart-device communications. Your first step in using SnapBridge is to download and install the SnapBridge app onto your smart device from the Google Play store or the Apple iTunes store. There are several ways to connect your Z6 to your device, either using the Setup menu’s Connect to Smart Device entry or by loading the SnapBridge app and using its Connect feature.

Make sure both Bluetooth is enabled on your smart device, and the Airplane mode in the Z6’s Setup menu is set to Off. Then follow these steps to link your camera and device using the camera’s Setup menu. Your screens may vary depending on whether you are using an Android or iOS device, and whether Nikon has issued one of its frequent updates to SnapBridge since this book went to press. Version 2.5.3 was current as I wrote this book. You may need to use your device’s Settings menu to connect to the camera, which will appear as a connection option in the device’s Bluetooth and Wi-Fi entries.

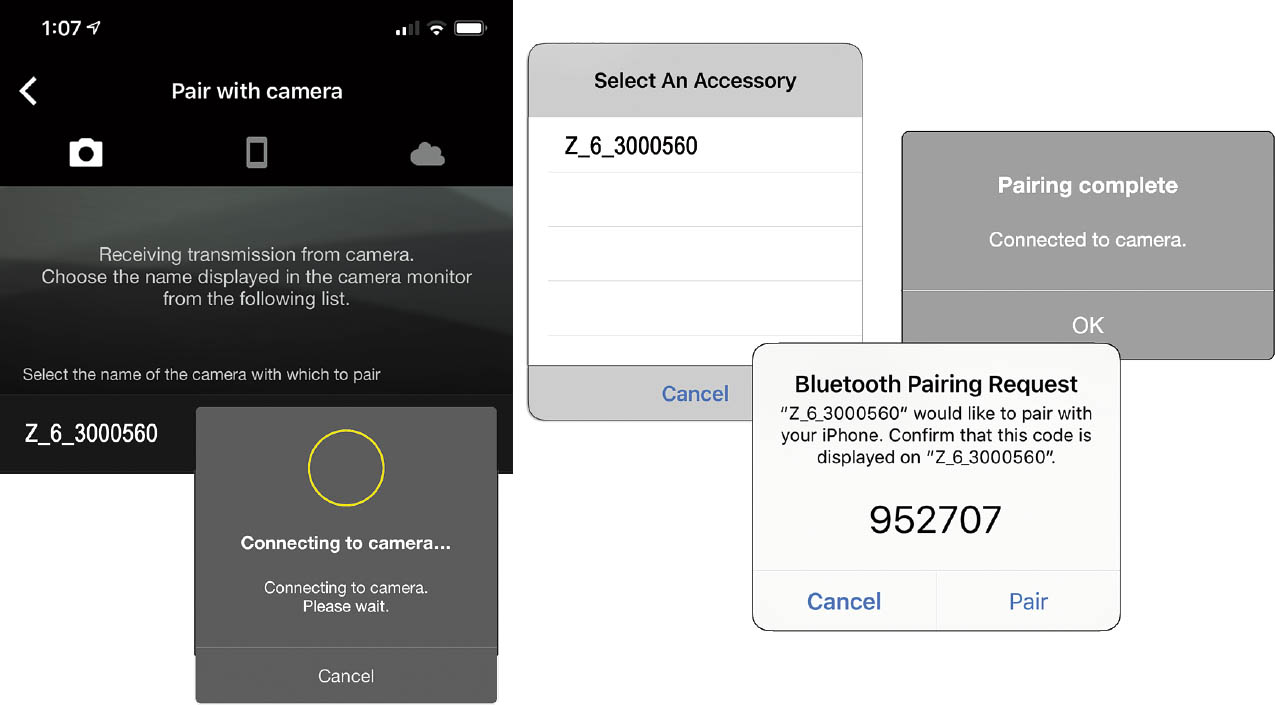

- 1. Open the SnapBridge app. Access the app on your device and tap the menu at upper right represented by three dots, and circled in green at left in Figure 6.17. Choose Add Camera from the screen that appears next. Select Mirrorless Camera in the next screen (Figure 6.17, center left), and then Pairing (Bluetooth) in the Connection Type screen seen center right in the figure.

- 2. Read the instructions. Help screens will appear telling you what to do next using the Z6’s Connect to Smart Device menu entry. Follow the directions, and tap Understood when you’ve followed them. The app will search for available connections.

Figure 6.17 Connecting to a smart device with SnapBridge.