Once upon a time, the ability to shoot video with a digital still camera was one of those “gee whiz” gimmicks camera makers seemed to include just to have a reason to get you to buy a new camera. That hasn’t been true for a couple of years now, as the video quality of many digital still cameras has gotten quite good. Indeed, feature films have been shot entirely or in part using Nikon dSLRs, and the Showtime television series Dexter included many scenes captured with a Nikon D800. The Z6 really ups the ante by incorporating video capabilities that have been enhanced or simply not available with previous Nikon still cameras.

The new 10-bit N-log recording option is a stellar example, bringing advanced color- and tonal-correcting capabilities to a lightweight but powerful camera that can capture Ultra HD (4K) and HD-quality video while outperforming typical modestly priced digital video camcorders—especially when you consider the range of lenses and other helpful accessories available for it that are not possible with more limited video-only devices.

But producing good-quality video is more complicated than just buying good equipment. There are techniques that make for gripping storytelling and a visual language the average person is very accustomed to seeing, but also unaware of. After all, by comparison we’re used to watching the best productions that television, video, and motion pictures can offer. Whether it’s fair or not, our efforts are compared to what we’re used to seeing produced by experts. While this book can’t make you a professional videographer, there is some advice I can give you that will help you improve your results with the camera.

There are many different things to consider when planning a video shoot, and when possible, a shooting script and storyboard can help you produce a higher-quality video.

Using an External Recorder

If you’re truly becoming an advanced videographer, you’ll probably be working with the Z6’s ability to output “clean” non-compressed HDMI video to an external monitor or video recorder, including the Atomos Shogun lineup, which includes versions that are quite affordable, at least in terms of professional video gear. You can choose models both with and without an external LCD monitor, and capture to solid-state drives (SSD), a laptop’s internal or connected hard drive, or to CFast memory cards (the latter chiefly as a nod to those still using the “fast” version of Compact Flash cards). Such equipment allows very high transfer rates and is certainly your best choice if you’re shooting 4K video.

Probably the best of the lot for Nikon Z6 owners is the Atomos Ninja V, an extremely portable unit with a 5.2-inch screen and a $695 price tag that’s currently the lowest for this type of device. (The only comparable monitor/recorder, the Video Devices PX-E5, costs $995.) Its size is a definite plus—if you’re shooting video with a smaller, lightweight camera, you’re going to need an equally compact recorder/monitor, such as the roughly 13-ounce Ninja V. Add a battery, HDMI cable, and a 2.5-inch solid state drive, and you’re ready to go.

The Ninja V has HDMI input and output jacks on its left edge, which you can see in Figure 15.1. The latter allows you to daisy-chain an even larger monitor or other device. A power button, headphone jack, microphone/audio input, and remote jack reside on the other edge. The touch screen enables you to view your video and access the monitor/recorder’s menus and controls, which is convenient (except outdoors in cold weather when you’re wearing gloves and might wish you had a few buttons to press instead). The only other “defect” of the unit is the noise produced by its fan; even when you’re using an external microphone with your Z6, the fan noise may be picked up in a quiet room.

Figure 15.1 The Atomos Ninja V monitor/recorder.

If you’re serious about video, the Nikon Z6 Filmmaker’s Kit ($3,999) is an attractive bundle that includes the Z6 with Nikkor S 24-70mm f/4 S lens, plus the FTZ adapter, the Atomos Ninja V, a Rode VideoMic Pro+ microphone, Moza Air 2 three-axis handheld gimbal, a coiled HDMI cable, and extra EN-EL15b battery. You can potentially save about $650 over buying these components separately. Nikon is throwing in a 12-month Vimeo Pro membership and an online course in how to make music videos, hosted by Chris Hersman, a Nikon Ambassador.

Why use an external monitor/recorder like the Ninja V, when your Z6 has its own nifty monitor and can store quite a lot of video on its XQD card? From a monitor standpoint, an external unit’s screen is larger, easier to see, and offers more flexibility in positioning. The Z6’s screen tilts up or down; mounted on a ballhead like the one in the figure, you can adjust an external screen to any angle, including reversing it to point in the same direction as the lens, so vloggers can monitor themselves as they record or stream their video blog.

But the best value may come from the recording capabilities of such a device. Internal video is saved to your memory card in the standard H.264/MPEG-4 Part 10 format as a MOV or MP4 file, which compresses that stream of images as much as 50X. That video has only 8 bits of information: good, but somewhat limited in the dynamic range that can be included. Depending on your scene, you may lose some detail in the highlights or shadows.

Fortunately, the Z6 can also simultaneously direct its video output through the HDMI port in “clean” uncompressed 4:2:2 10-bit UHD (ultra-high-definition) resolution. At the time I write this, your Z6 is the only full-frame mirrorless camera that can do that. You really get your two-bits’ worth of information: 8-bit output gives you 16.8 million possible colors; 10-bit output is capable of more than 108 billion hues. If your video stream to the external device uses N-log, the dynamic range (overall different tones that can be captured) increases dramatically.

TECH ALERT

Unless you’re venturing into professional videography, you probably aren’t obsessed with all those numbers in the previous paragraph. However, if you’re terminally curious, the important things to keep in mind are:

- Transfer bit rate. This is the speed the Z6 outputs its video to your memory card or external recorder. High transfer rates (such as 144 megabits per second) require fast memory cards; an external recorder should be able to suck up video as quickly as your camera can deliver it.

- Encoding. Although the “clean” video output to the HDMI port is not compressed, it is encoded using a procedure called chroma subsampling, which does reduce the amount of information that needs to be transferred. Chroma subsampling takes advantage of the fact that human beings don’t detect changes in color (chroma) as easily as they do for brightness (luma). The designation 4:2:2 simply indicates that the full amount of brightness information is passed along (“4”) while the two chroma values are sampled at half that rate (“2:2”). Subsampling in this way reduces the bandwidth of the otherwise uncompressed video signal by as much as one-third with no visual difference.

If you need even more control over your video output, Nikon has added firmware support for outputting video to the Ninja V that is repacked into Apple ProRes RAW video format (roughly the equivalent of still photo NEF files). RAW video was previously available only from dedicated video-only cameras.

When activated, the RAW data is output over the HDMI connection to the Ninja V, where it is stored on a removable SSD (solid state drive). When capture is completed, the SSD is connected to a computer using a USB cable. The ProRes RAW video can then be decoded and edited using compatible video software’s grading, color matching, and video FX features. An extra benefit: you can retain the RAW footage for re-editing later should your needs or editing technology change; your video is, in effect, future-proof.

The HDMI port on the Z6 accepts an HDMI mini-C cable. Nikon offers the HC-E1, but I prefer to purchase less-pricey third-party cables, which I buy in convenient lengths of 3 feet, 6 feet, 10 feet, or longer. The cable can be connected to the monitor, recorder, or other device of your choice. (Some of the screenshots in this book were output to a Blackmagic Intensity shuttle that allowed capturing stills of the Z6’s menus, live view, and video.) Here’s a recap of the information originally presented in Chapter 13, listing what you need to know to output to the HDMI port using the Setup menu options.

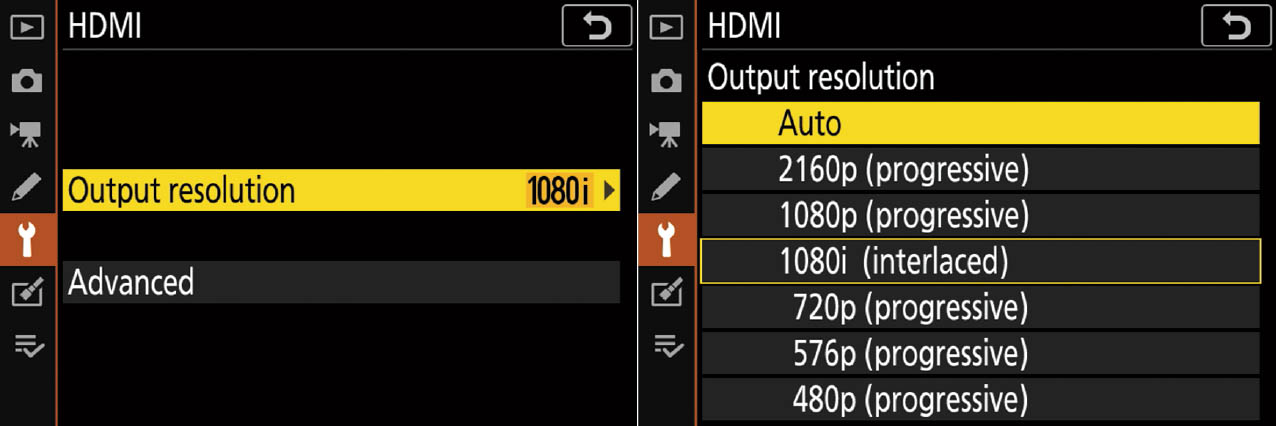

- Output Resolution. Select Auto and the camera will sense the correct output resolution to use. Auto will be applied (even if you select another resolution) when the HDMI port is used to display the camera’s image during movie live view, movie capture, and movie playback. I have found Auto will not work reliably with some devices, like my Intensity Shuttle, which works best when I use 1080i. If you’re having difficulties, you can manually set the Z6 to one of the available output resolutions individually until you find the best setting. (See Figure 15.2.)

If you want to use a different resolution, specific formats include 480p (640 × 480 progressive scan); 576p (720 × 576 progressive scan); 720p (1280 × 720 progressive scan); 1080p (1920 × 1080 progressive scan); or 1080i (1920 × 1080 interlaced scan). A 4K output option 2160p (3840 × 1260 progressive scan) is also available, and should be used only with a 4K-compatible device.

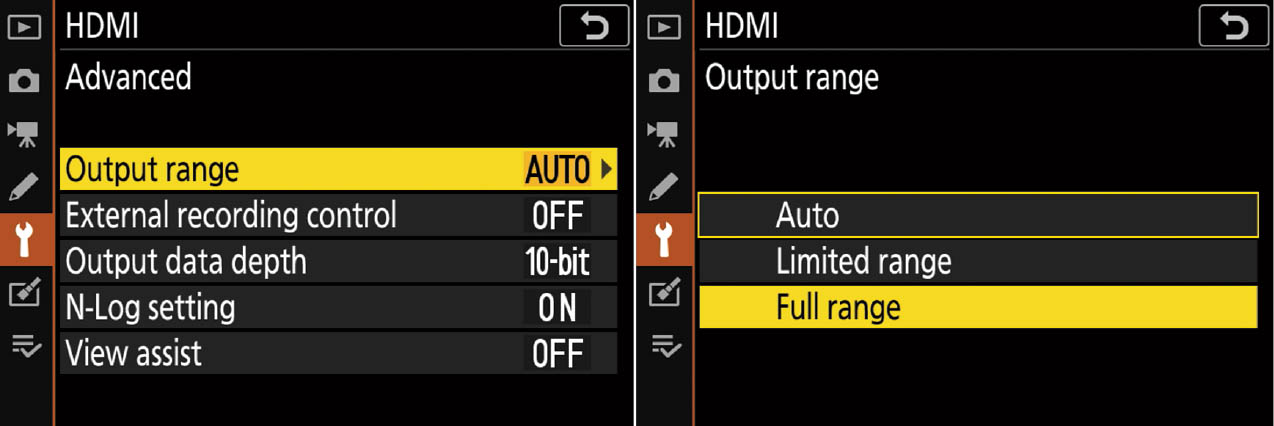

- Advanced. This cryptic entry leads you to a screen where you can select five more parameters:

- Output Range. Choose Auto (the default, and the best choice under most circumstances; it works fine with my Intensity Shuttle); Limited Range; or Full Range. The Z6 is usually able to determine the output range of your HDMI device. If not, Limited Range uses settings of 16 to 235, clipping off the darkest (0–16) and brightest (235–255) portions of the image. Use Limited Range if you’re plagued with reduced detail in the shadows of your image. Full Range may be your choice if shadows are washed out or excessively bright. It accepts video signals with the full range from 0 to 255. (See Figure 15.3.)

- External Recording Control. When enabled, this option allows you to use the camera controls to stop and start recording when connected to an external recorder (favored by serious videographers). The recorder must support the Atomos Open Protocol, used by the popular Atomos Shogun and Ninja recorders. When active, a STBY (Standby) or REC (Recording) icon appears on the live view monitor. This control is not available when shooting 4K or Slow-Mo video.

- Output Data depth. Choose 8-bit for normal output; if you want to use N-log, select 10-bit. That will make the two entries that follow available.

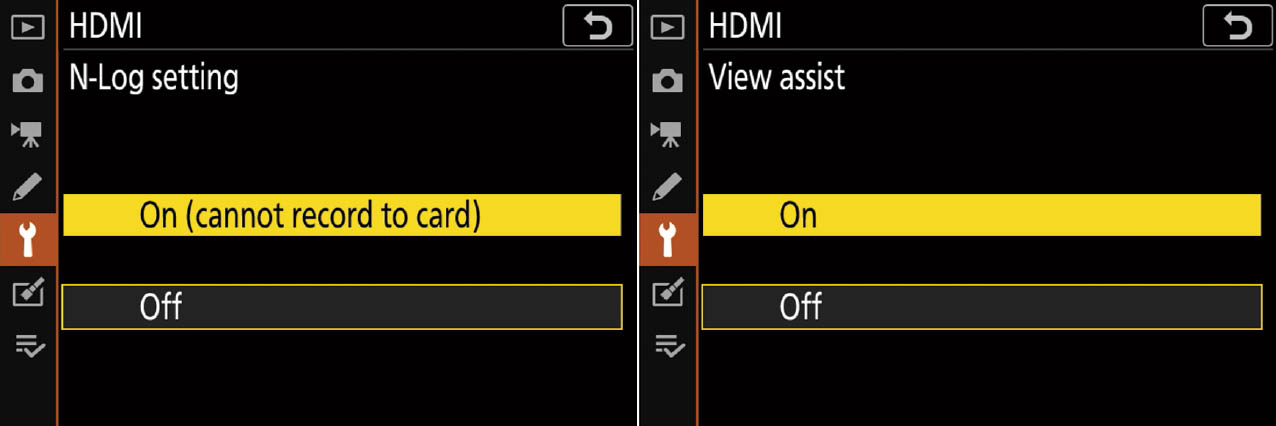

- N-Log Setting. If 10-bit data depth is enabled above, this entry is no longer grayed out and you may choose On to activate N-Log to an external recorder, as described next.

- View Assist. If N-Log is enabled, you can also turn on View Assist, described below.

Figure 15.2 Choose output resolution.

Figure 15.3 Select an output range.

As you’ve learned, the Z6 offers its own Log gamma adjustment, N-log, which captures a much longer dynamic range than standard gamma curves, compressing more tones into video and producing a much “flatter” (lower-contrast) raw image. Post-processing in a suitable video editor can manipulate the available tonal values (through a process called grading) to produce finished video with extended shadow detail without losing mid-tones and highlights. N-log gives you even better results than using the Flat Picture Control, which was also introduced with exactly this application in mind. The advantage of the Flat Picture Control is that you can apply it to the 8-bit output stored on your memory card; N-log 10-bit output must be stored on an external recorder. Of course, another way of increasing dynamic range is to religiously use the Z6’s Zebra function, described earlier, so you’ll know when you are risking blown highlights, and compensate for them (say, by changing your lighting).

To output using N-log to an external recorder, you must enable it, using the setting in the HDMI entry of the Setup menu (see Figure 15.4, left). The screen reminds you that if you turn N-log on, you cannot record the 10-bit output to your memory card and must have an external recorder attached. You’ll find that the N-log video looks extremely flat and is difficult to evaluate on your display screen. Nikon helps you by providing a View Assist option, also within the HDMI entry, that compensates with an adjusted, more natural-looking view. (See Figure 15.4, right.)

Figure 15.4 Activating N-log.

Refocusing on Focus

Although I explained the Z6’s autofocus and manual focus options in Chapter 5, there are some special considerations for focus when capturing video. The availability of usable AF when capturing movies, thanks to the Z6’s on-sensor PDAF, is extremely important. The camera now more quickly and reliably is able to gauge subject distance, tracking, and refocusing on subjects; you really don’t want inaccurate focus in video clips, where inconsistent focus is quite obvious when the movie is viewed.

Your three autofocus modes work extremely well. AF-S focuses once, and is useful for non-moving subjects; AF-C only refocuses while you’re holding down the shutter release or AF-On button. That’s particularly useful when you want to retain focus on a particular subject, but refocus at your command as needed when the subject moves. AF-F (Full-time AF) is available if you need the Z6 to refocus constantly as you capture. Use Custom Setting g4: AF Speed to control whether the camera refocuses quickly to follow a moving subject, or refocuses more slowly to switch from one subject to another. Custom Setting g5: AF Tracking Sensitivity can enable/disable the Z6’s ability to switch quickly when a different subject intervenes between the camera and the original subject. Both these fine-tuning behaviors can be used creatively to concentrate/deconcentrate attention on a particular subject or area of the frame.

Manual focus, with help from Focus Peaking (which is not available when using the Zebra feature), is an option, particularly for those who want to “pull” or “push” focus, a creative technique for redirecting the viewer’s attention from one subject to another, located in the foreground or background. The only complications are that the Z6’s electronic focus isn’t particularly linear, so a certain degree of rotation of the focus/control ring doesn’t result in the same amount of adjustment of the focus; in addition, experienced videographers may not like that the Nikon focus ring operates in the opposite direction of many/most other systems. While you can reverse the rotational direction of dials, you can’t do that with the focus/control ring. Since focusing is “by-wire” rather than mechanical, I believe Nikon could have added this option if it wanted to.

Lens Craft

I covered the use of lenses with the Z6 in more detail in Chapter 7, but a discussion of why lens selection is important when shooting movies may be useful at this point. In the video world, not all lenses are created equal. The two most important considerations are depth-of-field, or the beneficial lack thereof, and zooming. I’ll address each of these separately.

Depth-of-Field and Video

Have you wondered why professional videographers have gone nuts over still cameras that can also shoot video? The producers of Saturday Night Live could afford to have their director of photography use the niftiest, most-expensive high-resolution video cameras to shoot the opening sequences of the program. Instead, they opted for digital SLR cameras. One thing that makes digital still cameras so attractive for video is that they have relatively large sensors, which provides improved low-light performance and results in the oddly attractive reduced depth-of-field, compared with many professional video cameras.

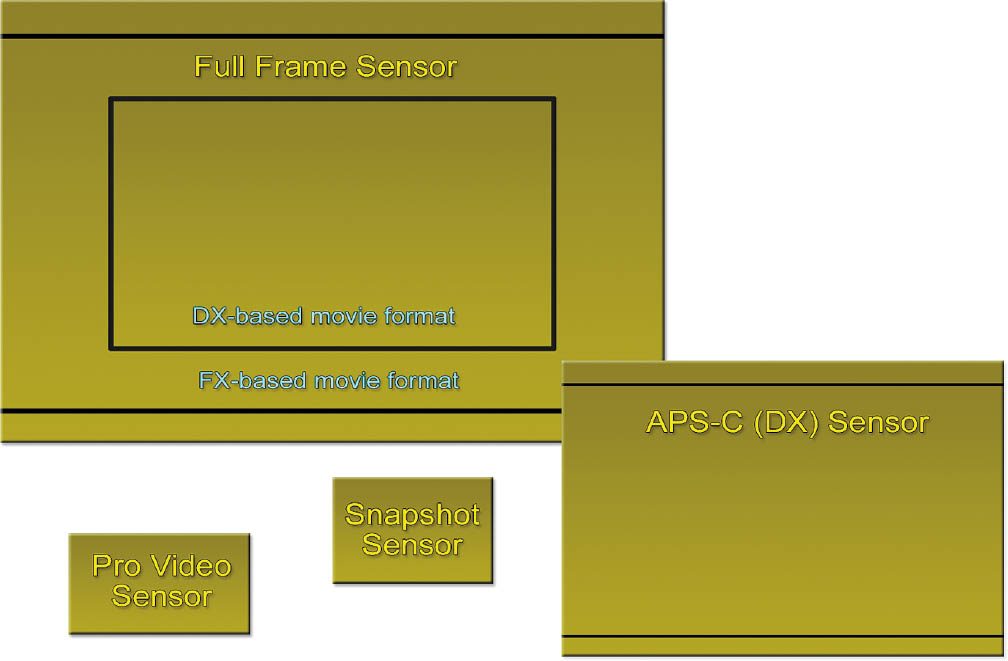

But wait! you say. No matter what size sensor is used to capture a video frame, isn’t the number of pixels in that frame the same? That’s true—the final resolution of a full HD 1080p video image is exactly 1920 × 1080 pixels. For standard HD (720p) the resolution is 1280 × 720 pixels (which the Z6 does not offer), and for ultra HD/4K (2160p), the resolution is 3820 × 2160 pixels. The final resolution, at least for the most common 1080p resolution, is the same, whether you’re capturing that frame with a point-and-shoot camera, a professional video camera, or a digital SLR like the Nikon Z6. But that’s only the final resolution. The number of pixels used to originally capture each video frame varies by sensor size.

For example, your Z6 does not use only its central 1920 × 1080 pixels to capture a full HD video frame. If it did that, you’d have to contend with a huge “crop” factor. That doesn’t happen! (See Chapter 7 for a longer discussion of the effects of the so-called “crop” factor.)

Instead, when the Z6 is set for FX-based movie format (which I’ll illustrate later in this chapter), it captures a video frame using an area that stretches across the full width of the sensor, measuring 6048 × 3402 pixels, using the proportions of a 16:9 area of its sensor (rather than the full 6048 × 4024 FX resolution of the sensor). That’s true for all HD formats: standard HD (720p), full HD (1080p), and ultra HD (4K, 2160p). In fact, the Z6 is the first Nikon dSLR to use the full width of the sensor to capture 4K video. (The D850 uses a cropped section of its DX/APS-C sensor.)

The pixels within that area are then sub-sampled using techniques described in the sidebar “More Tech,” using only some of the available photosites to reduce the captured frame to the final 3820 × 1260 or 1920 × 1080 video resolution. Your wide-angle and telephoto lenses retain roughly their same fields of view, and you can frame and compose your video through the viewfinder normally, with only the top and bottom of the frame cropped off to account for the wider video aspect ratio. (See Figure 15.5.)

Figure 15.5 The cropped video capture area for HD movies.

MORE TECH

The Z6 can capture 4K video from the full width of the sensor without pixel binning. Unlike its sibling, the Z7, the Z6 doesn’t need to use a technology called vertical line skipping, because its lower resolution (24 MP vs 46 MP with the Z7) doesn’t force the camera to “discard” lines to achieve 4K resolution. That gives the Z6 one advantage over the Z7; line skipping can result in reduced low-light efficiency, some unwanted moiré effects, and the appearances of some jagginess in diagonal lines.

In DX/APS-C/Super 35 capture mode, the Z6 oversamples each frame, and then combines them using pixel binning to create the finished video. Pixel binning is a type of algorithm that reads more pixels than the final output resolution needs (“oversampling”) and then combines groups of them to produce final pixels at the appropriate resolution (say a 4K video frame) that more accurately represent the colors of the image at an increased signal-to-noise ratio (for less noise and more sensitivity in very low-light scenes). Line skipping simply ignores some sensor values. The net result is that in FX mode, the Z6 gives you a great quality 4K image, but in DX/APS-C/Super 35 mode you can end up with even better video because of the additional processing.

As you learned in Chapter 7, a larger sensor calls for the use of longer focal lengths to produce the same field of view, so, in effect, a larger sensor like the full-frame FX sensor used in the Z6 has reduced depth-of-field. And that’s what makes cameras like the Z6 attractive from a creative standpoint. Less depth-of-field means greater control over the range of what’s in focus. Your Z6, with its larger sensor, has a distinct advantage over even DX models like the D850, is miles ahead of consumer camcorders in this regard, and even does a better job than many professional video cameras. (Some professional video cameras do use large sensors.) Figure 15.6 compares some typical sensor sizes.

Figure 15.6 Relative size of full frame, APS-C, snapshot, and pro-video sensors.

Zooming and Video

When shooting still photos, a zoom is a zoom is a zoom. The key considerations for a zoom lens used only for still photography are the maximum aperture available at each focal length (“How fast is this lens?), the zoom range (“How far can I zoom in or out?”), and its sharpness at any given f/stop (“Do I lose sharpness when I shoot wide open?”).

When shooting video, the priorities may change, and there are two additional parameters to consider. The first two I listed, lens speed and zoom range, have roughly the same importance in both still and video photography. Zoom range gains a bit of importance in videography, because you can always/usually move closer to shoot a still photograph, but when you’re zooming during a shot most of us don’t have that option (or the funds to buy/rent a dolly to smoothly move the camera during capture). But, oddly enough, overall sharpness may have slightly less importance under certain conditions when shooting video. That’s because the image changes in some way many times per second (24/30/60/120 times per second with the Z6), so any given frame doesn’t hang around long enough for our eyes to pick out every single detail. You want a sharp image, of course, but your standards don’t need to be quite as high when shooting video.

Here are the remaining considerations:

- Zoom lens maximum aperture. The speed of the lens matters in several ways. A zoom with a relatively large maximum aperture lets you shoot in lower light levels, and a big f/stop allows you to minimize depth-of-field for selective focus. Keep in mind that the maximum aperture may change during zooming. A lens that offers an f/3.5 maximum aperture at its widest focal length may provide only f/5.6 worth of light at the telephoto position.

- Zoom range. Use of zoom during actual capture should not be an everyday thing, unless you’re shooting a kung-fu movie. However, there are effective uses for a zoom shot, particularly if it’s a “long” one from extreme wide angle to extreme close-up (or vice versa). Most of the time, you’ll use the zoom range to adjust the perspective of the camera between shots, and a longer zoom range can mean less trotting back and forth to adjust the field of view. Zoom range also comes into play when you’re working with selective focus (longer focal lengths have less depth-of-field), or want to expand or compress the apparent distance between foreground and background subjects. A longer range gives you more flexibility.

- Linearity. Interchangeable lenses may have some drawbacks, as many photographers who have been using the video features of their interchangeable-lens digital cameras have discovered. That’s because, unless a lens is optimized for video shooting, zooming with a particular lens may not necessarily be linear. Rotating the zoom collar manually at a constant speed doesn’t always produce a smooth zoom. There may be “jumps” as the elements of the lens shift around during the zoom. Keep that in mind if you plan to zoom during a shot, and are using a lens that has proved, from experience, to provide a non-linear zoom. (Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to tell ahead of time whether you own a lens that is well-suited for zooming during a shot.)

Keep Things Stable and on the Level

Camera shake’s enough of a problem with still photography, but it becomes even more of a nuisance when you’re shooting video. The image-stabilization feature found in many Nikon lenses (and some third-party optics) can help minimize this. That’s why Nikon’s VR-capable zoom lenses (described in Chapter 7) make an excellent choice for video shooting if you’re planning on going for the handheld cinema verité look.

The Z6 also has an electronic VR option, which I’ve described several times in this book. It’s available only in 1080p mode (other resolutions, including 1920 × 1080 slow-motion and 4K are disabled). To recap, electronic vibration reduction reduces the frame size by about 10 percent (in FX mode only; in DX mode the camera has the pixels outside the APS-C frame to play with), and uses the extra image area to realign the frames to counteract any camera motion.

Just realize that while hand-held camera shots—even image stabilized—may be perfect if you’re shooting a documentary or video that intentionally mimics traditional home movie making, in other contexts it can be disconcerting or annoying. And even VR can’t work miracles. It’s the camera movement itself that is distracting—not necessarily any blur in your subject matter.

If you want your video to look professional, putting the Z6 on a tripod will give you smoother, steadier video clips to work with. It will be easier to intercut shots taken from different angles (or even at different times) if everything was shot on a tripod. Cutting from a tripod shot to a hand-held shot, or even from one hand-held shot to another one that has noticeably more (or less) camera movement can call attention to what otherwise might have been a smooth cut or transition.

Remember that telephoto lenses and telephoto zoom focal lengths magnify any camera shake, even with VR, so when you’re using a longer focal length, that tripod becomes an even better idea. Tripods are essential if you want to pan from side to side during a shot, dolly in and out, or track from side to side (say, you want to shoot with the camera in your kid’s coaster wagon). A tripod and (for panning) a fluid head built especially for smooth video movements can add a lot of production value to your movies.

ROLL ON, SHUTTER

Another side-effect to watch out for occurs when panning or capturing moving subjects, caused by the Z6’s rolling shutter. Because the camera captures all the horizontal lines one at a time, the last line in a frame is captured a fraction of a second later after the first line. So, if the subject or camera is moving from side to side, a vertical subject will appear to lean backward, causing what is termed a “Jell-O effect.” There’s no way to eliminate this defect, but you should be aware of it when shooting. You may be able to minimize capturing moving subjects, or edit offending clips out of your finished video.

Shooting Script

A shooting script is nothing more than a coordinated plan that covers both audio and video and provides order and structure for your video when you’re in planned, storytelling mode. A detailed script will cover what types of shots you’re going after, what dialogue you’re going to use, audio effects, transitions, and graphics. A good script needn’t constrain you: as the director you are free to make changes on the spot during actual capture. But, before you change the route to your final destination, it’s good to know where you were headed, and how you originally planned to get there.

When putting together your shooting script, plan for lots and lots of different shots, even if you don’t think you’ll need them. Only amateurish videos consist of a bunch of long, tedious shots. You’ll want to vary the pace of your production by cutting among lots of different views, angles, and perspectives, so jot down your ideas for these variations when you put together your script.

If you’re shooting a documentary rather than telling a story that’s already been completely mapped out, the idea of using a shooting script needs to be applied more flexibly. Documentary filmmakers often have no shooting script at all. They go out, do their interviews, capture video of people, places, and events as they find them, and allow the structure of the story to take shape as they learn more about the subject of their documentary. In such cases, the movie is typically “created” during editing, as bits and pieces are assembled into the finished piece.

Storyboards

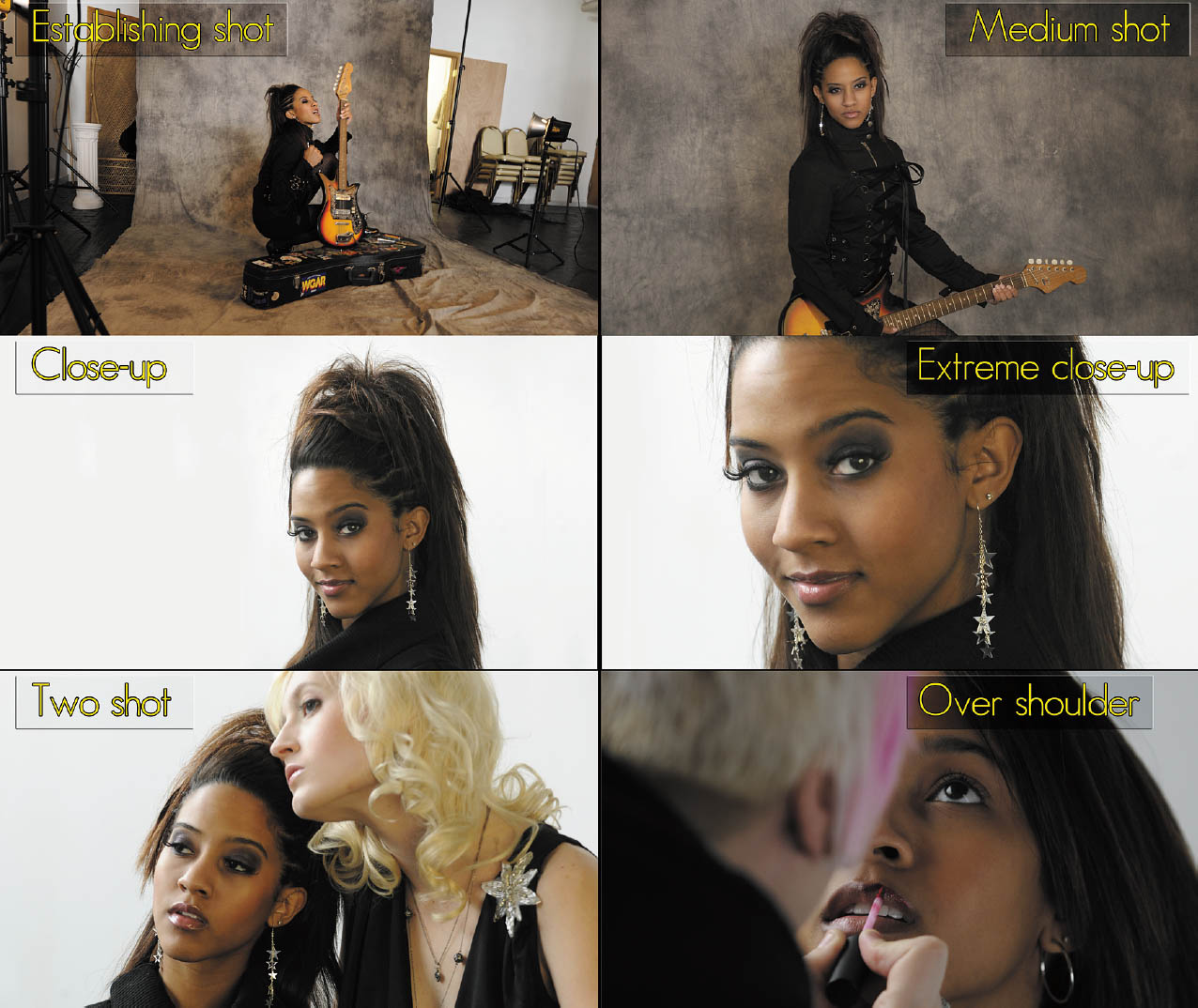

A storyboard makes a great adjunct to a detailed shooting script. It is a series of panels providing visuals of what each scene should look like. While the ones produced by Hollywood are generally of very high quality, there’s nothing that says drawing skills are important for this step. Stick figures work just fine if that’s the best you can do. The storyboard just helps you visualize locations, placement of actors/actresses, props and furniture, and helps everyone involved get an idea of what you’re trying to show. It also helps show how you want to frame or compose a shot. You can even shoot a series of still photos and transform them into a “storyboard” if you want, such as in Figure 15.7.

Figure 15.7 A storyboard is a series of simple sketches or photos to help visualize a segment of video.

Storytelling in Video

Today’s audience is used to fast-paced, short-scene storytelling. To produce interesting video for such viewers, it’s important to view video storytelling as a kind of shorthand code for the more leisurely efforts print media offers. Audio and video should always be advancing the story. While it’s okay to let the camera linger from time to time, it should only be for a compelling reason and only briefly. Above all, look for movement in your scene as you shoot. You’re not taking still photographs!

It only takes a second or two for an establishing shot to impart the necessary information. For example, many of the scenes for a video documenting a model being photographed in a rock ‘n’ roll music setting might be close-ups and talking heads, but an establishing shot showing the studio where the video was captured helps set the scene.

Provide variety too. If you put your shooting script together correctly, you’ll be changing camera angles and perspectives often and never leave a static scene on the screen for a long period of time. (You can record a static scene for a reasonably long period and then edit in other shots that cut away and back to the longer scene with close-ups that show each person talking.)

When editing, keep transitions basic! I can’t stress this one enough. Watch a television program or movie. The action “jumps” from one scene or person to the next. Fancy transitions that involve exotic “wipes,” dissolves, or cross fades take too long for the average viewer and make your video ponderous.

Composition

In movie shooting, several factors restrict your composition, and impose requirements you just don’t always have in still photography (although other rules of good composition do apply). Here are some of the key differences to keep in mind when composing movie frames:

- Horizontal compositions only. Some subjects, such as basketball players and tall buildings, just lend themselves to vertical compositions. But movies are shown in horizontal format only. So, if you’re interviewing a local basketball star, you can end up with a worst-case situation like the one shown in Figure 15.8. If you want to show how tall your subject is, it’s often impractical to move back far enough to show him full-length. You really can’t capture a vertical composition. Tricks like getting down on the floor and shooting up at your subject can exaggerate the perspective, but aren’t a perfect solution.

- Wasted space at the sides. Moving in to frame the basketball player as outlined by the yellow box in Figure 15.8 means that you’re still forced to leave a lot of empty space on either side. (Of course, you can fill that space with other people and/or interesting stuff, but that defeats your intent of concentrating on your main subject.) So, when faced with some types of subjects in a horizontal frame, you can be creative, or move in really tight. For example, if I was willing to give up the “height” aspect of my composition, I could have framed the shot as shown by the green box in the figure, and wasted less of the image area at either side.

Figure 15.8 Movie shooting requires you to fit all your subjects into a horizontally oriented frame.

- Seamless (or seamed) transitions. Unless you’re telling a picture story with a photo essay, still pictures often stand alone. But with movies, each of your compositions must relate to the shot that preceded it, and the one that follows. It can be jarring to jump from a long shot to a tight close-up unless the director—you—is very creative. Another common error is the “jump cut” in which successive shots vary only slightly in camera angle, making it appear that the main subject has “jumped” from one place to another. (Although everyone from French New Wave director Jean-Luc Goddard to Guy Ritchie—Madonna’s ex—have used jump cuts effectively in their films.) The rule of thumb is to vary the camera angle by at least 30 degrees between shots to make it appear to be seamless. Unless you prefer that your images flaunt convention and appear to be “seamy.”

- The time dimension. Unlike still photography, with motion pictures there’s a lot more emphasis on using a series of images to build on each other to tell a story. Static shots where the camera is mounted on a tripod and everything is shot from the same distance are a recipe for dull videos. Watch a television program sometime and notice how often camera shots change distances and directions. Viewers are used to this variety and have come to expect it. Professional video productions are often done with multiple cameras shooting from different angles and positions. But many professional productions are shot with just one camera and careful planning, and you can do just fine with your Z6.

Here’s a look at the different types of commonly used compositional tools:

- Establishing shot. Much as it sounds, this type of composition, as shown in Figure 15.9, upper left, establishes the scene and tells the viewer where the action is taking place. Let’s say you’re shooting a video of your offspring’s move to college; the establishing shot could be a wide shot of the campus with a sign welcoming you to the school in the foreground. Another example would be for a child’s birthday party; the establishing shot could be the front of the house decorated with birthday signs and streamers or a shot of the dining room table decked out with party favors and a candle-covered birthday cake. In the example, I wanted to show the studio where the video was shot.

Figure 15.9 Use a full range of shot types.

- Medium shot. This shot is composed from about waist to head room (some space above the subject’s head). It’s useful for providing variety from a series of close-ups and makes for a useful first look at a speaker. A medium shot is used to bring the viewer into a scene without shocking them. It can be used to introduce a character and provide context via their surroundings. (See Figure 15.9, upper right.)

- Close-up. The close-up, usually described as “from shirt pocket to head room,” provides a good composition for someone talking directly to the camera. Although it’s common to have your talking head centered in the shot, that’s not a requirement. In Figure 15.9, center left, the subject was offset to the right. This would allow other images, especially graphics or titles, to be superimposed in the frame in a “real” (professional) production. But the compositional technique can be used with Z6 videos, too, even if special effects are not going to be added. A close-up generally shows the full face with a little head room at the top and down to the shoulders at the bottom of the frame.

- Extreme close-up. When I went through broadcast training, this shot was described as the “big talking face” shot and we were actively discouraged from employing it. Styles and tastes change over the years and now the big talking face is much more commonly used (maybe people are better looking these days?) and so this view may be appropriate. Just remember, the Z6 is capable of shooting in high-definition video and you may be playing the video on a high-def TV; be careful that you use this composition on a face that can stand up to high definition. (See Figure 15.9, center right.) An extreme close-up is a very tight shot that cuts off everything above the top of the head and below the chin (or even closer!). Be careful using this shot since many of us look better from a distance!

- “Two” shot. A two shot shows a pair of subjects in one frame. They can be side by side or one in the foreground and one in the background. (See Figure 15.9, lower left.) This does not have to be a head-to-ground composition. Subjects can be standing or seated. A “three shot” is the same principle except that three people are in the frame. A “two shot” features two people in the frame. This version can be framed at various distances such as medium or close-up.

- Over-shoulder shot. Long a composition of interview programs, the “over-shoulder shot” uses the rear of one person’s head and shoulder to serve as a frame for the other person. This puts the viewer’s perspective as that of the person facing away from the camera. (See Figure 15.9, lower right.) An “over-shoulder” shot is a popular shot for interview programs. It helps make the viewers feel like they’re the one asking the questions.

Lighting for Video

Much like in still photography, how you handle light pretty much can make or break your videography. Lighting for video can be more complicated than lighting for still photography, since both subject and camera movement are often part of the process.

Lighting for video presents several concerns. First off, you want enough illumination to create a useable video. Beyond that, you want to use light to help tell your story or increase drama. Let’s take a better look at both.

Illumination

You can significantly improve the quality of your video by increasing the light falling in the scene. This is true indoors or out, by the way. While it may seem like sunlight is more than enough, it depends on how much contrast you’re dealing with. If your subject is in shadow (which can help them from squinting) or wearing a ball cap, a video light can help make them look a lot better.

Lighting choices for amateur videographers are a lot better these days than they were a decade or two ago. An inexpensive incandescent video light, which will easily fit in a camera bag, can be found for $15 or $20. You can even get a good-quality LED video light for less than $100. Work lights sold at many home improvement stores can also serve as video lights since you can set the camera’s white balance to correct for any color casts. You’ll need to mount these lights on a tripod or other support, or, perhaps, to a bracket that fastens to the tripod socket on the bottom of the camera.

Much of the challenge depends upon whether you’re just trying to add some fill-light on your subject versus trying to boost the light on an entire scene. A small video light will do just fine for the former. It won’t handle the latter. Fortunately, the versatility of the Z6 comes in quite handy here. Since the camera shoots video in Auto ISO mode, it can compensate for lower lighting levels and still produce a decent image. For best results though, better lighting is necessary.

Creative Lighting

While ramping up the light intensity will produce better technical quality in your video, it won’t necessarily improve the artistic quality of it. Whether we’re outdoors or indoors, we’re used to seeing light come from above. Videographers need to consider how they position their lights to provide even illumination while up high enough to angle shadows down low and out of sight of the camera.

When lighting for video, there are several factors to consider. One is the quality of the light. It can either be hard (direct) light or soft (diffused) light. Hard light is good for showing detail, but can also be very harsh and unforgiving. “Softening” the light, but diffusing it somehow, can reduce the intensity of the light but make for a kinder, gentler light as well.

While mixing light sources isn’t always a good idea, one approach is to combine window light with supplemental lighting. Position your subject with the window to one side and bring in either a supplemental light or a reflector to the other side for reasonably even lighting.

Lighting Styles

Some lighting styles are more heavily used than others. Some forms are used for special effects, while others are designed to be invisible. At its most basic, lighting just illuminates the scene, but when used properly it can also create drama. Let’s look at some types of lighting styles:

- Three-point lighting. This is a basic lighting setup for one person. A main light illuminates the strong side of a person’s face, while a fill light lights up the other side. A third light is then positioned above and behind the subject to light the back of the head and shoulders. (See Figure 15.10, left.)

- Flat lighting. Use this type of lighting to provide illumination and nothing more. It calls for a variety of lights and diffusers set to raise the light level in a space enough for good video reproduction, but not to create a mood or emphasize a scene or individual. With flat lighting, you’re trying to create even lighting levels throughout the video space and minimize any shadows. Generally, the lights are placed up high and angled downward (or possibly pointed straight up to bounce off a white ceiling). (See Figure 15.10, right.)

- “Ghoul lighting.” This is the style of lighting used for old horror movies. The idea is to position the light down low, pointed upward. It’s such an unnatural style of lighting that it makes its targets seem weird and “ghoulish.”

- Outdoor lighting. While shooting outdoors may seem easier because the sun provides more light, it also presents its own problems. As a rule of thumb, keep the sun behind you when you’re shooting video outdoors, except when shooting faces (anything from a medium shot and closer) since the viewer won’t want to see a squinting subject. When shooting another human this way, put the sun behind her and use a video light to balance light levels between the foreground and background. If the sun is simply too bright, position the subject in the shade and use the video light for your main illumination. Using reflectors (white board panels or aluminum foil–covered cardboard panels are cheap options) can also help balance light effectively.

Figure 15.10 With three-point lighting (left) two lights are placed in front and to the side of the subject and another light is directed on the background to provide separation. Flat lighting (right) was bounced off a white ceiling and walls to fill in shadows as much as possible. It is a flexible lighting approach since the subject can change positions without needing a change in light direction.

Audio

When it comes to making a successful video, audio quality is one of those things that separates the professionals from the amateurs. We’re used to watching top-quality productions on television and in the movies, yet the average person has no idea how much effort goes in to producing what seems to be “natural” sound. Much of the sound you hear in such productions is recorded on carefully controlled sound stages and “sweetened” with a variety of sound effects and other recordings of “natural” sound. Google “Foley artist” some time and you’ll discover this part of a production is, indeed, a rich and complex art form.

Tips for Better Audio

Since recording high-quality audio is such a challenge, it’s a good idea to do everything possible to maximize recording quality. Here are some ideas for improving the quality of the audio your camera records:

- Get the camera and its microphone close to the speaker. The farther the microphone is from the audio source, the less effective it will be in picking up that sound. While having to position the camera and its built-in microphone closer to the subject affects your lens choices and lens perspective options, it will make the most of your audio source. Of course, if you’re using a very wide-angle lens, getting too close to your subject can have unflattering results, so don’t take this advice too far. It’s important to think carefully about what sounds you want to capture. If you’re shooting video of an acoustic combo that’s not using a PA system, you’ll want the microphone close to them, but not so close that, say, only the lead singer or instrumentalist is picked up, while the players at either side fade off into the background.

- Use an external microphone. You’ll recall the description of the camera’s external microphone port in Chapter 2. As noted, this port accepts a stereo mini-plug from a standard external microphone, allowing you to achieve considerably higher audio quality for your movies than is possible with the camera’s built-in microphones (which are disabled when an external mic is plugged in). An external microphone reduces the amount of camera-induced noise that is picked up and recorded on your audio track. (The action of the lens as it focuses can be audible when the built-in microphones are active.)

The external microphone port can provide plug-in power for microphones that can take their power from this sort of outlet rather than from a battery in the microphone. Nikon provides optional compatible microphones such as the ME-1 ($135) (see Figure 15.11) or wireless ME-W1 ($199); you also may find suitable microphones from companies such as Shure and Audio-Technica. If you are on a quest for superior audio quality, you can even obtain a portable mixer that can plug into this jack, such as the affordable Rolls MX124 (around $150) (www.rolls.com), letting you use multiple high-quality microphones (up to four) to record your soundtrack.

One advantage that a sound-mixing device offers over the stock Z6 is that it adds an additional headphone output jack to your camera, so you can monitor the sound actually being captured by the recorder (you can also listen to your soundtrack through the headphones during playback, which is way better than using the Z6’s built-in speaker). The adapter has two balanced XLR microphone inputs and can also accept line input (from another audio source), and provides cool features like AGC (automatic gain control), built-in limiting, and VU meters you can use to monitor sound input.

Figure 15.11 Nikon ME-1 external stereo microphone.

- Hide the microphone. Combine the first few tips by using an external mic, and getting it as close to your subject as possible. If you’re capturing a single person, you can always use a lapel microphone (described in the next section). But if you want a single mic to capture sound from multiple sources, your best bet may be to hide it somewhere in the shot. Put it behind a vase, using duct tape to fasten the microphone, and fix the mic cable out of sight (if you’re not using a wireless microphone).

- Turn off any sound makers you can. Little things like fans and air handling units aren’t obvious to the human ear, but will be picked up by the microphone. Turn off any machinery or devices that you can plus make sure cell phones are set to silent mode. Also, do what you can to minimize sounds such as wind, radio, television, or people talking in the background.

- Make sure to record some “natural” sound. If you’re shooting video at an event of some kind, make sure you get some background sound that you can add to your audio as desired in post-production.

- Consider recording audio separately. Lip-syncing is probably beyond most of the people you’re going to be shooting, but there’s nothing that says you can’t record narration separately and add it later. It’s relatively easy if you learn how to use simple software video-editing programs like iMovie (for the Macintosh) or Windows Movie Maker (for Windows PCs). Any time the speaker is off-camera, you can work with separately recorded narration rather than recording the speaker on-camera. This can produce much cleaner sound.

External Microphones

The single-most important thing you can do to improve your audio quality is to use an external microphone. The Z6’s internal stereo microphones mounted on the front of the camera will do a decent job, but have some significant drawbacks, partially spelled out in the previous section:

- Camera noise. There are plenty of noise sources emanating from the camera, including your own breathing and rustling around as the camera shifts in your hand. Manual zooming is bound to affect your sound, and your fingers will fall directly in front of the built-in mics as you change focal lengths. An external microphone isolates the sound recording from camera noise.

- Distance. Anytime your Z6 is located more than 6 to 8 feet from your subjects or sound source, the audio will suffer. An external unit allows you to place the mic right next to your subject.

- Improved quality. Obviously, Nikon wasn’t able to install a super-expensive, super-high-quality microphone, even on a $2,000 camera. Not all owners of the Z6 would be willing to pay the premium, especially if they didn’t plan to shoot much video themselves. An external microphone will almost always be of better quality.

- Directionality. The Z6’s internal microphone generally records only sounds directly in front of it. An external microphone can be either of the directional type or omnidirectional, depending on whether you want to “shotgun” your sound or record more ambient sound.

You can choose from several different types of microphones, each of which has its own advantages and disadvantages. If you’re serious about movie making with your Z6, you might want to own more than one. Common configurations include:

- Shotgun microphones. These can be mounted directly on your Z6, although, if the mic uses an accessory shoe mount, you’ll need the optional adapter to convert the camera’s shoe to a standard hot shoe. I prefer to use a bracket, which further isolates the microphone from any camera noise. One thing to keep in mind is that while the shotgun mic will generally ignore any sound coming from behind it, it will pick up any sound it is pointed at, even behind your subject. You may be capturing video and audio of someone you’re interviewing in a restaurant, and not realize you’re picking up the lunchtime conversation of the diners seated in the table behind your subject. Outdoors, you may record your speaker, as well as the traffic on a busy street or freeway in the background.

- Lapel microphones. Also called lavalieres, these microphones attach to the subject’s clothing and pick up their voice with the best quality. You’ll need a long enough cord or a wireless mic. These are especially good for video interviews, so whether you’re producing a documentary or grilling relatives for a family history, you’ll want one of these.

- Hand-held microphones. If you’re capturing a singer crooning a tune, or want your subject to mimic famed faux newscaster Wally Ballou, a hand-held mic may be your best choice. They serve much the same purpose as a lapel microphone, and they’re more intrusive—but that may be the point. A hand-held microphone can make a great prop for your fake newscast! The speaker can talk right into the microphone, point it at another person, or use it to record ambient sound. If your narrator is not going to appear on-camera, one of these can be an inexpensive way to improve sound.

- Wired and wireless external microphones. This option is the most expensive, but you get a receiver and a transmitter (both battery-powered, so you’ll need to make sure you have enough batteries). The transmitter is connected to the microphone, and the receiver is connected to your Z6. In addition to being less klutzy and enabling you to avoid having wires on view in your scene, wireless mics, such as the Nikon MW-W1, let you record sounds that are physically located some distance from your camera. Of course, you need to keep in mind the range of your device, and be aware of possible signal interference from other electronic components in the vicinity.

WIND NOISE REDUCTION

Always use the wind screen provided with an external microphone to reduce the effect of noise produced by even light breezes blowing over the microphone. Many mics, such as the Nikon ME-1, include a low-cut filter to further reduce wind noise. However, these can also affect other sounds. You can disable the low-cut filters for the ME-1 by changing a switch on the back from L-cut (low cutoff) to Flat. Other external mics also have their own low-cut filter switch.

Special Features

The Z6 also has two audio frequency ranges (Wide and Vocal Range) and an Attenuator, described in Chapter 11, so you can tailor your microphone capture to your subject matter (for ambient sound or voice recording). Audio levels can be adjusted while recording, and the camera’s internal microphones have improved wind noise reduction.