CHAPTER

NINETEEN

INTERNATIONAL BOND MARKETS AND INSTRUMENTS

Senior Vice President and Director of Bonds

Fidelity Management and Research Company/Pyramis Global Advisors

This chapter will focus on the important role of international bond markets as a source of funding for major corporations, sovereigns, and supranationals, as well as the instruments used in this market. After defining the breadth of the international bond market and providing historical context on the growth and motivations for issuing debt in this market, the primary instruments used in this market—domestic bonds, Eurobonds, and foreign bonds—will be described in detail. Importantly, the key differences between the dollar-denominated and non-dollar-denominated bonds will be explained as well as some of the vehicles investors and debt issuers use to access these markets. Finally, the risk and return components resulting from currency exposure in non-dollar-denominated bonds will be highlighted, as will the merits of hedging this component of risk.

OVERVIEW AND SCOPE OF INTERNATIONAL BOND MARKETS

With more than 60% of all fixed income securities trading outside of the United States, investor interest in international bond markets has risen substantially in the first decade of the twentieth century. While the total face value of fixed income securities in the U.S. remains significantly larger than that of its closest peers—the Eurozone region1 and Japan, respectively—the breadth of international debt instruments has greatly expanded. For example, between 2000 and 2010, global fixed income markets grew at an annual rate of nearly 10%. Much of that growth was concentrated in lesser developed countries.2

Domestic bonds often are included in diversified portfolios because their price movements are generally less volatile than equities, they pay a known amount of interest at regular intervals, and they repay principal at maturity (unless default takes place). U.S. dollar–denominated international bonds behave much like domestic U.S. domestic bonds. For the U.S.-based investor, international bonds generally consist of bonds issued in markets outside of the United States that can be denominated in dollars or other currencies. However, for the U.S.-based investor, the behavior and returns of non-dollar-denominated bonds tend to be more volatile because of the currency component.

Since the 1980s, the sophistication of debt issuers has increased at the same time as currency and global interest rate markets multiplied in size. In addition, the access to continuous market information and the development of robust pricing tools such as Bloomberg have resulted in greater transparency and ease of issuance. As a result, borrowing in the international bond market has flourished.

Historical Context

The broader trend toward issuing debt instruments globally is not recent, however. Cross-border investments in government bonds were common before World War I. By 1920, Moody’s was providing credit ratings on over 50 sovereign borrowers. Yet, most of these foreign investments ended badly for U.S. investors. Hyperinflation under the German Weimar Republic of the 1920s rendered the Reichsmark worthless. Similarly, during the 1920s, U.S. investors saw their foreign investments decline in U.S. dollar terms by 86% in France, 70% in Italy, and 50% in Spain. Interestingly, some of the countries that avoided sharp devaluations during this period including the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Argentina have seen their bonds lose much of their value since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in the 1970s.

Between 1930 and 1970, capital controls and domestic regulations sharply curtailed cross-border bond investment. The development of offshore markets and the growth of international banking institutions led the way toward greater cross-border investment flows in the early 1980s, prompting governments to reverse course. Market reforms liberalizing capital flows in money, bond, and equity markets were introduced to bolster domestic capital markets and to attract foreign capital.

The elimination of capital controls in many countries as well as advances in the dissemination of information led issuers and investors to focus on opportunities in international bond instruments. Indeed, according to data compiled by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the nominal value of global outstanding debt3 increased from $35 trillion in 2000 to more than $90 trillion in 2010. Bonds denominated in U.S. dollars are consistently the largest single component of the world bond market. However, international debt issued in other currencies, such as euro dollars, yen, and emerging market denominations continue to gain market share.

One indicator demonstrating the willingness of borrowers to broaden their universe of funding opportunities is the share of debt issued in domestic versus international markets. Between 2000 and 2010, global borrowers doubled their issuance of international bonds to nearly 30% of total global debt outstanding. Issuers in the United States and the Eurozone shifted to international bond markets most aggressively during this period. In Japan, however, nondomestic debt issuance remained close to nil over this 10-year period.

Although the sheer size of the U.S. economy ensures a central role for U.S. bonds in world capital markets, the growth in volume and the expansion of participating countries in the international bond sector is a long-term trend. In particular, the gradual removal of currency trading restrictions in countries such as China, which limit foreign investment, will accelerate this global trend. This chapter will provide a broad overview of the instruments, markets, and participants in international bond investing. First, the instruments and markets for the dollar-denominated sector of the international bond market are described. Then, the non-dollar-denominated sectors of the international bond market as well as vehicles used to access these markets are outlined. Finally, we focus extensively on the contribution of currency to returns and volatility for U.S. dollar–based investors.4

Motivations for International Bond Issuance

The financing techniques used in these international bond markets rival those in the U.S. domestic market in terms of sophistication. Sovereigns, quasi-government, and foreign government entities, financial institutions, and corporate issuers typically vie for the lowest borrowing costs regardless of currency and country. Issuing debt on an international scale broadens the pool of potential investors, potentially lessens regulatory burdens, and allows the construction of more customized investment strategies. Regardless of their motivation, the instruments used by issuers generally fall into several well-defined categories.

THE INSTRUMENTS: DOMESTIC, EURO, AND FOREIGN

International bonds are divided into three general categories: domestic, euro, and foreign. The classification depends on the domicile of the issuer, the nature of the underwriting syndicate, the domicile of the primary buyers, and the currency denomination. Domestic bonds are issued, underwritten, and traded under the currency and regulations of a country’s domestic bond market by a borrower located within the country. Eurobonds are underwritten by an international syndicate and traded outside any one domestic market. Foreign bonds are issued under the regulations of a domestic market and are intended primarily for that country’s domestic investors by a foreign-domiciled borrower.

Examples of international bonds:5

Domestic Bond: A Japanese based company issues debt in Japan with principal and interest payments denominated in Japanese Yen.

Eurobond: A Japanese based company issues debt in Germany with principal and interest payments denominated in Japanese Yen.

Foreign Bond: A Japanese based corporation issues debt in Germany with principal and interest payments denominated in Euro Dollars.

The most decisive influence on the price or yield of an international bond is its currency denomination. For U.S. investors, the pertinent division is between international bonds denominated in U.S. dollars and those denominated in other currencies. Regardless of the domicile of the issuer, the buyer, or the trading market, prices of issues denominated in U.S. dollars (dollar-denominated) are affected principally by the direction of U.S. interest rates, whereas prices of issues denominated in other currencies (non-dollar-denominated) are determined primarily by movement of interest rates in the country of the currency denomination. Thus, for U.S. dollar–based investors, the analysis of international bond investing can be separated into two parts: dollar-denominated bonds and nondollar-denominated bonds.

Most dollar-denominated international bonds can be included in a domestic bond portfolio with little change to the management style and overall risk profile of the portfolio. In most cases, a marginal extra effort is required to analyze the credits of unfamiliar issuers and incorporate the settlement procedures for these bonds. The notable exception in the dollar-denominated bond sector is in emerging market debt, which, as detailed below, can be far more volatile than most other dollar-denominated bonds.

The currency component of non-dollar-denominated bonds, however, introduces a fair degree of return volatility, and has a far different risk profile than domestic U.S. and dollar-denominated international bonds. The question of currency hedging (either passive, active, or not at all), plus considerations of trading hours, settlement procedures, withholding taxes, and other nuances of trading non-dollar-denominated international bonds, requires greater risk and portfolio management oversight.

DOLLAR-DENOMINATED INTERNATIONAL BONDS

The dollar-denominated international bond market includes Eurodollar bonds, which are issued and traded outside any one domestic market, and Yankee bonds, which are issued and traded primarily in the United States. In addition, global bonds are issued in both the Yankee bond and Eurodollar bond markets simultaneously. Domestic investors, however, are generally indifferent between global and straight Yankee bond issues except where liquidity differs.

Emerging market debt traditionally had been primarily issued in dollars; however, over the past decade, domestic (local currency) debt issuance has vastly surpassed dollar-denominated debt issuance. In addition to these instruments, Regulation 144A Private Placements and Euro Medium Term Note markets are often denominated in dollars. Before examining these instruments in depth, some of the more basic questions regarding dollar-denominated international bonds should be addressed.

Why Do Foreign-Domiciled Issuers Borrow in the U.S. Dollar Markets?

The U.S. bond market is the largest, most liquid, and most sophisticated of the world’s bond markets. By issuing in the U.S. market, foreign entities diversify their sources of funding. Also, as companies have become more global in production and distribution, they have assets and liabilities in many different currencies and hence are less tied to their domestic bond markets. Financial innovations, particularly the advent of the interest-rate and currency swap markets, have greatly expanded the diversity of borrowers, notably in the corporate sector.

Companies in need of floating-rate financing often have been able to combine a fixed-coupon bond with an interest-rate swap to create a cheaper means of finance than a traditional floating-rate note. Similarly, when currency swap terms are favorable, a company in need of funding can issue debt outside their domestic market and use swaps to hedge the associated currency risk. For example, a U.K. based institution seeking funding could issue a Eurodollar bond and combine it with a currency swap to create a cheaper source of funds than a traditional U.K. sterling denominated bond issue.

Why Should U.S. Dollar–Based Investors Be Interested in Dollar-Denominated International Bonds?

Investors may be able to find a higher yield on a dollar-denominated international bond than on other comparably rated issues, especially where the credit may be less familiar to United States investors. Moreover, these debt issues can offer sector and credit diversification. Yankee bonds are registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and trade like any other U.S. domestic bond. The credit quality of issuers in the Yankee bond market is generally strong. Eurodollar bonds generally are less liquid than Yankee bonds, but sometimes can offer more attractive yields and a broader list of available credits.

What Are the Differences between a Yankee Bond and a Eurodollar Bond?

The primary difference is SEC registration. Yankee bonds are registered with the SEC and are issued and traded in the United States. Eurodollar bonds are issued outside the United States in unregistered, or bearer form, and are traded primarily by foreigners. Eurodollar bonds are issued mostly by corporate issuers, whereas Yankee bonds are issued mostly by high-credit quality sovereign and sovereign-guaranteed issuers. The size of the Eurodollar bond market historically has been larger than the size of the Yankee bond market. Finally, Yankee bonds pay interest semiannually, whereas Eurodollar bonds carry annual coupons.

Eurodollar Bonds

The Eurobond market existed long before the launch of the pan-European currency known as the euro. In the international bond market, the prefix Euro- has come to mean offshore, or debt issues that are marketed outside any domestic jurisdiction in a denomination other than the local currency.

The Eurodollar banking market began during the Cold War. The Soviet Union, wary that the United States might freeze their dollar deposits, preferred to hold their dollar-denominated bank deposits outside the reach of the U.S. authorities. The Eurodollar market6 continued to grow as banks sought to avoid domestic banking restrictions such as Regulation Q, which set a ceiling on interest levels paid on deposits, and the Glass-Steagall Act, which prohibited banks from engaging in underwriting and brokerage. In addition, restrictions placed on direct investment overseas by U.S. companies in 1968 encouraged companies to raise capital offshore, thus increasing the size of the Eurobond market.

However, the most significant growth in the Eurodollar market occurred in the late 1970s as the recycling of large dollar surpluses by OPEC countries (since oil is denominated in dollars) injected huge amounts of liquidity into the market. Balance-of-payments deficits, due in part to higher oil prices, also increased sovereign and sovereign-guaranteed Eurodollar issuance.

While eurobonds encompass securities of all different currency denominations, Eurodollar bonds are by far the largest single component of the Eurobond market. Eurodollar bonds are:

1. Denominated in U.S. dollars

2. Issued and traded outside the jurisdiction of any single country

3. Underwritten by an international syndicate

4. Issued in bearer (unregistered) form

5. Pay investors interest and principal payments in dollars

A Eurobond that is denominated in dollars is called a Eurodollar bond. Since Eurodollar bonds are not registered with the SEC as U.S. domestic new issues are required to be, underwriters are legally prohibited from selling new issues to the U.S. public. However, once the bond has traded in the secondary market for a certain period of time, or seasoning period, such sales are permissible. An issue is usually considered seasoned 40 days after it has been initially offered. This seasoning requirement effectively locks U.S. investors out of the primary market. Even though a portion of Eurodollar bonds end up in U.S.-based portfolios after the seasoning period expires, the lack of participation by U.S. investors in new offerings means that foreign investors dominate this market. Although no single location has been designated for Eurodollar bond market making, London is the de facto primary trading center.

The first Eurodollar bond issue was in 1957 by Petrofina, a Belgian petroleum company for the small amount of $5 million. Marketability of Eurodollar bonds has improved as the market has grown. In the past, many straight fixed-coupon Eurobonds traded infrequently, particularly among the older issues, which were often only $50 million or less in individual issue size. Normal issue size today is $200 to $500 million or higher.

Despite the increase in market size, liquidity remains constrained since demand is typically driven by buy and hold investors. As a result, trading volumes can be lower than other comparable debt while bid/ask spreads can be wider. Since Eurodollar bonds are held in unregistered form, details about major holders are often unreliable. Market participants estimate that retail investors participate extensively in the Eurobond market by directly purchasing these instruments or participating via mutual funds.

Borrowers in the Eurodollar bond market may be divided into four primary issuers: supranational agency, sovereign, financial and corporate. Supranational agencies, such as the World Bank and the European Investment Bank, are consistently among the top borrowers, reflecting their constant need for development financing and their lack of “home” issuance market.

Sovereign and sovereign-backed borrowers are also prominent, although the growth in sovereign Eurodollar bond issuance slowed in the late 1980s as governments either cut back on their external borrowing in favor of their domestic bond markets or chose to borrow in the non-dollar markets to diversify their currency exposure. Similarly, fiscal retrenchment in many emerging market sovereigns and the growth of domestic bond markets have served to reduce the role that sovereign issuers play in this market. Bank and finance companies continue to dominate the new issuance market; however, corporate issuance has increased.

One driver of growth in the Eurodollar bond market is the general economic climate. In the late 1980s, Japanese companies were among the most active issuers in this market due to large borrowing needs and limited foreign participation in its domestic bond markets. However, the opening up of the Japanese domestic bond market (thus diminishing the relative attractiveness of issuing debt in the offshore market) and the deleveraging by companies as the economy fell into a long-running recession led to a sharp drop in Eurodollar bond issuance.

The strength in the dollar from 1987 to 1990 and again in the late 1990s increased investor appetite for dollar-denominated securities and encouraged Eurodollar bond issuance. Similarly, the dollar’s weakness versus the yen from 1994 to 1995 and versus the euro dollar from 2003 to 2008, led to reduced issuance of Eurodollar bonds by international borrowers as investor appetite abated.

Similarly, following the introduction of the euro in 1999, many traditional Eurodollar bond issuers could also look to pan-European sources of funding denominated in euro dollars. Increased competition between regional underwriters also resulted in the decline in underwriter gross spreads and lower borrowing costs for issuers. Conversely, during the 2007–2009 credit crisis, Eurodollar bond market liquidity diminished leading to higher borrowing costs, and market access was limited to the highest quality issuers.

Over the long term, however, the size and vitality of the market likely will be decided by policy decisions regarding the regulation of financial markets and securities. As national governments deregulate their domestic bond markets, the attraction of Eurodollar bonds to issuers and investors diminished. However, greater scrutiny by regulators in the United States following the 2007–2009 credit crises as well as the growth of the global bond market could once again fuel Eurodollar bond issuance.

Yankee Bonds

The other portion of the dollar-denominated international bond market is referred to as the Yankee bond market. This market encompasses foreign-domiciled issuers who register with the SEC and borrow dollars via issues underwritten by a U.S. syndicate for delivery in the United States.7 An example of a Yankee bond would be a Japanese based company which issues debt in the United States with principal and interest payments denominated in U.S. dollars. The principal source of demand is in the United States, although foreign buyers can and do participate.

Unlike Eurodollar bonds, which do not have registration requirements, companies offering Yankee bonds are subject to strict requirements to ensure that they are financially stable and capable of making payment when the bonds reach maturity. In general, any bond not registered with the SEC cannot be sold to U.S. citizens at the time of the issue. Yankee bond issuers usually face a four-week registration period and ongoing disclosure requirements. At the same time, the registration period review generally provides investors with greater clarity regarding the new issue. As a result, Yankee bonds tend to be viewed as lower in risk than other types of foreign bond securities which have not been similarly vetted.

The Yankee bond market is much older than the Eurodollar bond market. Overseas borrowers first issued Yankee bonds in the early 1900s. The repayment record of these early issues, however, was not good; as much as one-third of the outstanding “foreign” bonds in the United States were in default on interest payments by the mid 1930s. After years of slow growth, the market expanded rapidly after the abolition of the interest-equalization tax in 1974.8 Since then, the Yankee bond market has become a critical source of financing for international issuers second only to the Eurobond market.

Supranational agencies, Canadian provinces (including provincial utilities), and financial institutions historically have been the most prominent Yankee bond issuers, comprising well over half the total market. Issuing in the Yankee bond market is preferred by many institutions that need to borrow significant amounts but cannot access such liquidity in their local markets or who can identify more attractive borrowing terms abroad. Secondary market trading for Yankee bonds tends to be more liquid leading to smaller bid/ask spreads compared with Eurodollar bond offerings. Moreover, using Yankee bonds can at times be appealing to debt issuers because of the attractive terms to swap the bonds back to local currencies.

Regulatory measures meant to boost the capital levels of financial institutions also prompted issuance in the Yankee bond market. For example, between 2001 and 2010, in order to boost capital levels and comply with proposed stricter banking regulations, European banks issuance of Yankee debt increased nearly fourfold.

The corporate sector, which is a growing borrower in the Eurodollar bond market, is of only minor importance in the Yankee bond market. The increased use of global bonds, however, has blurred the distinction between the Yankee and Eurodollar bond markets.

The Market for Eurodollar and Yankee Bonds

Foreign investors play a role in the Yankee market, although the market’s location in the United States prevents foreigners from having as dominating a presence as they have in the Eurodollar bond markets. Prior to 1984, foreign investors had a preference for dollar-denominated international bonds which included both Yankee bonds and Eurodollar bond issues. These instruments were not subject to the 30% withholding tax imposed by the U.S. government on all interest paid to foreigners.

When the withholding tax exception was abolished in July 1984, a major advantage of these dollar-denominated international bonds over U.S. Treasuries and domestic corporate bonds was eliminated. This made Yankees and Eurobonds less attractive relative to the U.S. domestic market. However, foreign investor demand remained robust due to the yield differential between the U.S. domestic bond market and the dollar-denominated bond market. Yankee bonds and Eurodollar bonds tend to offer a higher yield because of lower liquidity and perceived lower credit quality relative to U.S. domestic debt. Moreover, foreign buyers are often more familiar with these credits than they are with U.S. domestic credits. Finally, Yankee and Eurodollar issuers sometimes compensate foreign investors in the dollar-denominated market by offering bonds with features that traditionally appeal to them, including shorter maturities and structures with greater call protection.

For these reasons, when foreign buyers seek exposure to dollar-denominated bonds, they often buy dollar-denominated international bonds—Eurodollar or Yankee—instead of U.S. domestic issues. The degree of interest of foreign buyers in dollar-denominated securities, or lack thereof, is reflected in narrowing or widening of the yield spread to U.S. Treasury bonds. This is particularly true of Eurodollar bonds because foreign interest governs this market to a greater extent than the Yankee market which is instead more attuned to U.S. investor preferences.

The fact that the Eurodollar bond market and the Yankee bond market have different investor bases occasionally leads to trading disparities between the two markets. For example, similarly structured Canadian Yankee bonds often trade at lower yields than Canadian Eurodollar bonds because U.S. investors tend to be more comfortable with Canadian credits due to the close proximity of the two countries.

Global Bonds

The globalization of the investment world has brought the Yankee bond and Eurodollar bond markets closer together, and it is not uncommon for investors to arbitrage the two markets when yield disparities appear. The advent of the global bond blurred the dividing line between the two markets. A global bond is normally a large international bond offering by a single borrower that is simultaneously sold in multiple currencies in North America, Europe, Asia, and other regions. Institutional investors are the primary purchasers of these instruments.

The World Bank issued the first global bond in 1989, with a $1.5 billion issue that was placed simultaneously in both the Yankee bond and the Eurodollar bond markets. Since investors purchased and traded the security in both Europe and the United States, liquidity was greater, while issuance costs (compared to several separate Eurobond issues) were lower. Although these securities were in registered form unlike Eurodollar bonds, investors valued the larger, more liquid nature of these bond issues more than the anonymity offered by bearer bonds.

The rationale for the global bond was to create an instrument that had attributes of both a Yankee bond and a Eurodollar bond. As a result, the market segmentation that inhibited liquidity and created yield disparities would be eliminated. The success of global bond issues is further evidence of the melding of the Eurobond markets and domestic debt markets that has lowered barriers to cross-border capital movements. Issuers that can consistently borrow across markets and currencies using global bond instruments because of their strong credit profiles also tend to be viewed positively by investors.

The global bond market has been used primarily by central governments and supranational organizations. Frequent global bond issuers include development banks such as the Asian Development Bank and World Bank, and sovereigns such as the Republic of Brazil and the United Mexican States. These institutions issue liquid benchmark bonds across the yield-curve which, in turn, increases price transparency and reduces borrowing costs.

Regulation 144A Private Placements

To encourage international firms to issue debt in the United States while minimizing costs associated with disclosure, the Securities and Exchange Commission enacted Regulation 144A (Reg 144A) in 1990. Privately placed fixed income securities are sold directly to a limited number of sophisticated investors (such as insurance companies, pension funds, and certain high net worth individual investors) and are exempt from registration with the SEC.

Since the SEC ruling, the Reg 144A market has become a trillion dollar market with most issues rated by the major credit-rating agencies. U.S. companies are the predominant issuer in this market followed by European multinationals, and the majority of issuance remains dollar-denominated. Initially Reg 144A securities, due to the somewhat smaller issuance size, offered slightly higher yields versus public debt instruments. As the Reg 144A market has grown, however, this differential has decreased.

Reg 144A provides foreign borrowers with greater access to institutional investors. Since issuers only need to disclose the documentation required by their home-market regulators, they do not need to follow the more cumbersome SEC registration process. Many private companies prefer this market in order to maintain confidentiality with regard to their financial statements. Other institutions employ Reg 144A offerings in order to create and distribute more customized debt products. Many Reg 144A offerings are issued with registration rights that allow the issuer quick access to capital and the ability to broaden the issue’s size if desired by registering with the SEC.

Major insurance companies, pension funds, and long-term institutional asset managers are traditionally the largest investors in this market. Reg 144A debt offerings potentially offer investors diversification benefits which result from stricter covenant protections and credit enhancement. Generally, international issuers looking to access investors in this market need to offer these additional incentives to reassure investors given limited financial disclosure.

Euro Medium Term Note Market

Euro Medium Term Notes (EMTNs) allow for debt issuance in different currencies and maturities under one umbrella agreement. This agreement is similar to a “shelf registration” in which investors can issue debt on multiple occasions for a specified period of time but need only file one offering prospectus. Thus borrowers can use EMTNs to tap the markets more quickly and efficiently than with traditional Eurodollar bonds which require separate documentation for each bond issue. Although EMTNs were used originally only for non-underwritten private placements, they are now often underwritten by syndicates also. As a result, the distinction between Eurobonds and EMTNs has also blurred. Because these securities are offered outside of the United States, they are not subject to filing or review requirements with the SEC.

The majority of all Eurobond issues are swapped into floating-rate debt. At times, market opportunities to obtain favorable swap terms can be limited. As a result, borrowers respect the flexibility of EMTN programs. The maturity and other issue terms can be structured to suit specific investor needs, which in turn allow companies to opportunistically issue debt. These notes have been used extensively for small, illiquid, structured private issuance. As the EMTN market has gained traction, larger, more standard debt issues have become common and often compete with offerings in the Eurodollar bond and Reg 144A markets.

Dollar-Denominated Emerging Market Debt

Emerging market bonds are often found in international bond portfolios. Initially, most of these bonds were denominated in U.S. dollars or other major currencies such as sterling or deutsche marks. However, non-dollar-denominated debt instruments, such as Mexican Cetes, soon became widely available to international investors over time. One of the key milestones that marked the growth of the dollar-denominated emerging market bond market was the development of the Brady Bond market.

Brady Bonds were named after U.S. Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady, who developed a market-oriented approach to the Latin American debt crisis in the 1980s by repackaging nonperforming bank loans into marketable securities. As a result, commercial banks could remove these loans from their balance sheets. The first Brady Bond agreement was reached with Mexico, and the bonds were issued in March 1990. At its peak, the nominal value of the Brady bonds outstanding was approximately $130 billion.

Most countries have since retired their Brady bond debt, instead turning to cheaper financing through Eurobond issues or domestic credit market issuance. Emerging market sovereign issuers returned to financial markets following the Latin American debt crisis to issue dollar-denominated and non-dollar-denominated debts at attractive yields.

Regardless of currency denomination, emerging market debt investors need to consider the additional risk characteristics of these securities. The reasons for default can include not just the inability to service debt but also the potential for the government to favor some creditors versus other creditors. Investors need to monitor not just credit quality in emerging market debt, but also political risk.

The market risk of holding emerging market securities has generally been higher than the risk of holding developed country credits. While many emerging market sovereign defaults such as those in Ecuador (2008), Belize (2006), and the Dominican Republic (2005) have had little impact on broader financial markets, other sovereign defaults such as Russia (1998) and Argentina (2001) created significant regional and even global credit market stress.

The developed country financial markets largely escaped the turmoil of the 1997 Asian crisis; however, they were severely affected by the Russian default in August 1998. The resulting flight to safety not only damaged emerging market bond prices and overall confidence, but also led to a sharp widening of U.S. corporate and agency spreads.

Investor confidence in emerging market debt was once again battered between 1999 and 2002 when Latin America faced another round of economic distress. The devaluations of the Brazilian real and the Argentine peso and the sovereign default of Argentina pressured emerging markets globally. Although both events shook financial markets, the outcomes were very different. Brazil pursued a path of fiscal austerity and inflation targeting, and reentered the sovereign debt markets shortly thereafter. Argentina, on the other hand, defaulted on both its local debt and foreign currency debt, and could not borrow in the international debt markets nearly a decade later.

The credit crisis of 2007–2009 also created great stress on emerging market debt as investors who had been seeking higher yielding securities collectively unwound their positions in these foreign markets and shifted to “safer” assets such as U.S Treasuries. However, once again, investors returned to these same emerging market sovereigns as the crisis subdued and growth prospects once again appeared attractive.

Ironically, while emerging market sovereign debt regained favor following this crisis, many sovereigns in developed markets—particularly in Europe—remained fragile. Large structural deficits, weak banking systems, and low growth prospects at the close of the decade led investors to question the fiscal sustainability of sovereigns such as Ireland, Greece, Portugal, and Spain. Even the bond markets of Italy and France were sorely tested. Many “developed” sovereign debt traded cheaper to traditional “emerging market” debt. These concerns significantly weighed on financial market participants despite the purchase of securities by the European Central Bank in the secondary market and the creation of various extraordinary liquidity facilities by the governments of Eurozone countries.

As a result of this crisis, the delineation between emerging markets and developed markets became less obvious. More than 50% of emerging market debt issuers now have investment-grade ratings by the major rating agencies. More importantly, debt issued in the currency of these sovereigns has become a rapidly growing segment of the international fixed income markets. Investor demand has shifted from dollar-denominated debt to non-dollar-denominated debt issued in domestic bond markets.

NON-DOLLAR-DENOMINATED DEBT INTERNATIONAL BONDS

From the standpoint of the U.S. investor, non-dollar-denominated international bonds encompass all issues denominated in currencies other than the dollar. The currency component introduces a significant source of volatility. The most important question facing U.S. investors investing in non-dollar-denominated international bonds is whether or not to hedge currency exposure. The theoretical underpinnings of the currency hedge question, however, are beyond the scope of this chapter, but understanding the various perspectives is important.

Just as in the U.S. bond market, non-dollar-denominated fixed income instruments are determined by the domicile of the issuer and the location of the primary trading market, The three major venues are: the domestic market; the foreign market where the issuer is domiciled outside of the country of issuance; and the Euro market, which trades outside of any national jurisdiction.

The Non-U.S. Domestic Markets

Securities issued by a borrower within its home market and in that country’s currency typically are termed domestic issues. These may include bonds issued directly by the government, government agencies, and corporations. In most countries, the domestic bond market is dominated by government-backed issues, central government issues, government agency issues, and state (provincial) or local government issues. The United States has the most well-developed, actively traded corporate bond market, followed by Europe. In contrast, Japanese corporations rely heavily on bank loans instead of corporate debt issuance. As a result, the corporate bond market in Japan tends to be illiquid.

As discussed in the previous section, non-dollar-denominated debt issued in emerging markets has been a rapidly growing segment of the international bond market. These domestic markets have exhibited significant growth for a number of reasons, including the liberalization of currency controls, the implementation of sound economic and regulatory practices, and the desire to attract additional potential sources of liquidity.

Many emerging market nations tend to continuously issue dollar-denominated debt at specific points on the yield-curve. These benchmark issues tend to be liquid and offer greater pricing transparency for international investors. As liquidity in these offshore markets develops, local debt markets tend to follow as an important source of borrowing. For these sovereigns, issuing debt in their own currency rather than in dollars allows a better matching of liabilities with assets.

Moreover, a deep, liquid domestic bond market generally promotes the growth of corporate debt markets which reduces the reliance for companies to borrow only from banks. By issuing debt in both the domestic market and the dollar-denominated markets, issuers access a broader set of investors, lower borrowing costs, and reduce the risks associated from currency fluctuations and exogenous events.

Increased liquidity in domestic emerging market debt markets offers international fixed income investors access to a much broader set of debt instruments (beyond dollar-denominated debt). Indeed, between 2000 and 2010, the market for local currency debt doubled in size relative to the dollar-denominated market. The diversification benefits offered by emerging market debt have been a key driver of demand.

Bulldogs, Samurais, and Other Foreign Bonds

The foreign bond market consists of debt sold primarily in one country and currency by a borrower of a different nationality. The Yankee bond market is the U.S. dollar version of this market. Other examples are the Samurai market, which consists of yen-denominated bonds issued in Japan by non-Japanese borrowers, and the Bulldog market, which is composed of U.K. sterling denominated bonds issued in the United Kingdom by non-British entities.

Other foreign bond markets (many with colorful names) include those in the emerging markets. Some of these foreign bonds include Matrioshka bonds (Russian ruble-denominated bond issued in the Russian Federation by non-Russian entities), Arirang bonds (Korean won-denominated bond issued by a non-Korean entity in the Korean market), Panda bonds (Chinese renimbi-denominated bond issued by a non-China entity in the People’s Republic of China market), and Dim sum bonds (Chinese renimbi-denominated bond issued by a Chinese entity in Hong Kong).

Relative to the size of their domestic bond markets, these foreign bond markets are small, and liquidity can be limited. For borrowers, the major advantage of the foreign bond markets is access to a broader set of investors in the country in which the bonds are issued. The Samurai market, for example, allows borrowers to tap the huge pools of investment capital in Japan. For investors, foreign bonds offer the convenience of domestic trading and settlement and often additional yield. However, the increasing liquidity and diversification benefits offered by domestic bond markets (including currency and duration exposure) have slowed the growth of the foreign bond markets.

The Offshore Non-Dollar-Denominated Market

Securities issued directly into the international (“offshore”) markets are called Eurobonds. Eurobonds can be issued in any currency such as euros, Japanese yen, South African rand, or Czech koruna. The Eurobond market encompasses any bond not issued in a domestic market, regardless of issuer nationality or currency denomination. Eurodollar bonds are the U.S. dollar-denominated version of Eurobonds. These securities typically are underwritten by international syndicates and are sold in a number of national markets simultaneously. They may or may not be obligations of, or guaranteed by, an issuer domiciled in the country of currency denomination. Issuers include sovereigns, corporations, and supranationals. As with the foreign bond markets, the liquidity of Eurobonds is typically less than the liquidity of domestic government issues.

Most Eurobonds have been issued in dollars and euro dollars. However, between 2000 and 2010, dollar-denominated Eurobond issuance declined. The decline of the share of the U.S. dollar in Eurobond issuance can be traced to three general trends: the depreciation of the dollar versus other major currencies from its peak in 1984, a desire by major institutions to diversify currency exposure and funding sources, and the liquidity offered by the swaps and other derivatives markets.

Accessing International Bond Markets through Other Vehicles

Adding international bonds to a fixed income portfolio has allowed investors to broaden their investable universe. At the same time, investors can enjoy the benefits of diversification. However, for individual investors, accessing these markets can be difficult as a result of lack of transparency in prices, wide bid/ask spreads and costly transaction fees. As individual investors have become more educated regarding the characteristics of international bonds, investment products have been developed that offer more efficient access to these markets. Two products that have seen a large inflow of funds and have in turn fostered the growth of international debt markets include global bond mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.

International Bond Mutual Funds

Although many international bond funds and emerging market debt funds have been in operation since the late 1980s, the real growth of these products commenced in the past decade. These bond mutual funds have been particular beneficiaries of investor demand for additional yield, yet still remain a small part of total fixed income mutual fund assets. Of the over $2 trillion in taxable bond funds as of December 2010, about $200 billion was invested in international fixed income assets.9

U.S. investors typically have added these funds to their portfolio for diversification purposes and to gain non-dollar exposure. With daily pricing transparency and professional active or passive management, global bond funds offer investors another avenue to access the international debt markets.

Bond funds that invest in fixed income assets abroad encompass many strategies. More generally, however, three primary categories exist: emerging markets debt funds, global bond funds, and international bond funds. Emerging market debt funds invest the majority of their assets in emerging market countries which are determined by specific rating agency criteria. Global bond funds invest in debt both within the United States and abroad. As a result, these funds incur U.S. dollar exposure. International bond funds, however, maintain no exposure to U.S. dollars since their assets are invested in countries excluding the United States. Corporate, sovereign, supranational or other debt could all be potential investment based on the individual guidelines of each bond fund.

International Bond Exchange-Traded Funds

Just as global bond mutual funds offer a breadth of strategies and opportunities for investors, exchange-traded funds (ETFs) dedicated to fixed income—and in particular international fixed income—have greatly increased in size. Of the nearly $1 trillion in assets dedicated to ETFs as of December 2010, about 15% of these assets were invested in fixed income strategies. International fixed income ETFs totaled just about 5% of total fixed income ETF assets though this segment continues to grow rapidly.

ETFs have certain characteristics that have made them attractive to investors. Like a traditional mutual fund, public investors claim an undivided interest in a pool of securities and other assets. The shares of many ETFs often trade on the secondary market at prices close to the net asset value of the shares, rather than at discounts or premiums.10 Many have lower expense ratios and certain tax efficiencies compared with mutual funds, and they all allow investors to buy and sell shares at intra-day market prices. Moreover, investors can sell ETF shares short, write options on them, and set market, limit, and stop-loss orders on them.

Bond ETFs usually track well recognized bond indices such as the Barclays Global Bond Aggregate Index, the Citigroup World Government Bond Index, and the JP Morgan Emerging Market Bond Index. These indices represent a segment of the bond market by maturity, sector, and/or quality. Methods such as stratified sampling can reduce the number of bonds that need to be purchased to match a particular index or strategy. Actively managed bond ETFs may employ customized benchmarks and engage in various strategies, including the use of leverage when managing their international bond and currency exposures. Moreover, these strategies can take different approaches to hedging currency exposure.

INTERNATIONAL FIXED INCOME AND UNDERSTANDING CURRENCY RISK

While the diversification benefits of adding international bonds to a global portfolio of assets is generally assumed to be positive, the foreign currency element often overwhelms any other return component. For single country foreign bond investments, currency risk contributes up to 95% of overall risk as measured by volatility according to various studies.11 The volatility and return objectives of each investor will drive the decision to hedge, partially hedge, or not hedge currency exposure.

Hedging and its implications for international bond portfolio management is a controversial topic. Some well-regarded academic studies conclude that for investors with long-term horizons, the volatility of a hedged portfolio of bonds exceeds the volatility of the equivalent unhedged portfolio. Specifically, mean reversion toward purchasing power parity provides a “natural hedge.” As a result, not hedging currency exposure is better over long-term horizons (for bond portfolios, greater than seven years).12 This argument suggests that an unhedged portfolio over long-term horizons would also offer higher returns versus a hedged portfolio.

However, other more studies offer a different conclusion. According to a sample of international bond returns between 1975 and 2009, full hedging of bond portfolios was determined to be the optimal strategy in almost all cases up to five years.13 In addition, depending on the base currency of the investor, hedging of currency risk meaningfully affects returns.

Components of Return

To the dollar-based investor, there are two components of return in actively managed dollar-denominated bond portfolios: coupon income and capital gains. Capital gains can result from either interest-rate movements or a change in the perceived creditworthiness of the issuer. Also, because of the characteristic of bonds to “pull to par” (or call price), time also plays a factor in capital gains.

In non-dollar-denominated investing, a third component of return must be considered: foreign currency movements. The U.S. investor must couple the domestic capital gain with income and then translate the total domestic return into dollars to assess the total return in U.S. dollars.

For the U.S. investor in foreign-currency bonds, the prospects for return not only should be viewed in an absolute sense, but also should be analyzed relative to returns expected in the U.S. market. The analysis can be separated into three questions.

Are International Bond Returns Entirely

a Function of Currency Movements?

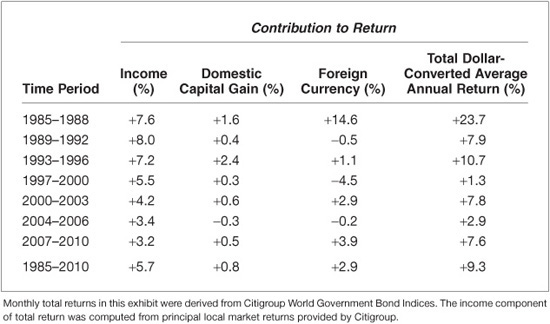

The answer to this question depends on the time horizon. Exhibit 19–1 shows that in six of the eight interim periods, including the 25 year period between 1985 and 2010, the income component of return proved to be the largest of the three return components, as measured by the Citigroup Non-U.S. World Government Bond Index.

EXHIBIT 19–1

Average Annual Returns of International Bond Index by Components by Regime

Over shorter time horizons, however, foreign currency or domestic capital gains can be significantly more important. This result is similar to more recent research which states that hedging currency exposure for risk reduction purposes in international bond portfolios is prudent in time horizons of up to five years. While volatility can be reduced in these portfolios, returns can also be meaningfully limited.

Exhibit 19–2 breaks down the 1985–2010 period into annual returns to demonstrate the influence of domestic capital changes and movements in exchange rates on total returns over the short term. Domestic capital gains ranged from –10.0% in 1994 to +9.3% in 1993, and currency returns varied from –12.6% in 2005 to +25.5% in 1987. (Recall that negative foreign currency returns for dollar-based investors correspond to a strengthening in the dollar versus other currencies, and vice versa.) The income component of return varied in a much narrower range throughout the period, from a low of +2.9% in 2010 to a high of +8.3% in 1990.

EXHIBIT 19–2

Average Annual Returns of International Bond Index by Component

For individual countries, the variation in components of return can be much greater. Currency movements can be the most volatile component of return, with historical annual gains or losses as high as 20% to 30% against the U.S. dollar. Capital gains have proved much less volatile but still can generate double-digit gains or losses during periods of interest-rate volatility.

Lastly, although the income component is by definition always positive, it too can vary substantially from country to country, as noted in the comparison of bond yields in Japan and New Zealand in the discussion later in the chapter. These data show clearly that U.S.-based investors need to factor all of these components of return—income, capital change, and currency movement-on an absolute level as well as relative to U.S. alternatives.

What Is the Initial Yield Level Relative to Yield Levels on U.S. Bonds?

When the non-dollar-denominated debt issue has a higher yield relative to U.S. bonds, the income advantage will, over time, provide a cushion against a decline in the foreign bond price relative to U.S. bonds or against deterioration in the value of the foreign currency. The longer the time horizon, the greater the cushion provided by this accumulating income.

On the other hand, if the initial yield on the non-dollar-denominated debt is lower than that of comparable U.S. bonds, this income shortfall must be offset. To provide comparable returns, the foreign currency needs to appreciate relative to the U.S. dollar, or the bond needs to initially trade at a discount relative to U.S. bonds in order to realize a capital gain.

This latter situation when initial yields are lower than U.S. bond yields may appear less palatable for investors. However, between 1970 and 1980, bonds with the lowest income levels actually had the best dollar returns. This same result was achieved in the 1980s, when Japanese yen bonds had the world’s best total returns in U.S. dollar terms despite the fact that yen bonds offered the lowest interest rates of the world’s major bond markets. The underlying rationale for this result is that bonds with low yields are denominated in currencies of countries with low inflation rates which theoretically translates into currency appreciation relative to the U.S. dollar.

Between 2000 and 2010, investors in many non-dollar-denominated debt markets benefited not only from a general decline in overall interest rates, but also a continued appreciation of these currencies versus the U.S. dollar. The high returns led to strong institutional and retail investor demand. Even the credit crisis of 2007–2009 did little to deter these trends.

What Are the Prospects for Capital Gains Relative to Expectations for U.S. Bond Prices?

This factor can be broadly discussed in terms of changing yield spreads of nondollar-denominated bonds versus dollar-denominated issues in the same way that changing yield spreads are analyzed within the domestic U.S. market. However, several points should be considered with regard to this analogy. First, in the U.S. market, all bond prices generally move in the same direction, although not always to the same extent, whereas domestic price movements of non-dollar-denominated bonds may move in the direction opposite to that of the U.S. market.

Second, although yield-spread relationships within the U.S. market may deviate at times, in most cases there is a normal well-understood correlation. However, changing economic, social, and political trends between the United States and other countries suggest that there are few reliable relationships to serve as useful guidelines over the long term in non-dollar-denominated bonds.

Third, investors must be aware that similar interest-rate shifts may result in significantly different capital price changes. Both U.S. and international investors are very familiar with the concept of duration; that is, that equal interest rate movements will result in differing price movements depending on the individual security’s current yield, maturity, coupon, and call structure. However, since international bond investors are typically focused on the higher absolute yield of these securities versus the benchmark market, they often pay less attention to the consequences of duration on similar-maturity bonds across markets.

For example, the low yield on Japanese long bonds, currently around 1.3%, makes Japanese 10-year bond prices about 15% more sensitive to changes in yield than New Zealand bonds, where yields are about 5.5%.

Thus, a 20-basis point (0.2%) decline in the yield of a 10-year New Zealand fixed-coupon government issue starting at a 5.5% yield results in a 1.55% price change, whereas the same 20-basis point move for a 10-year Japanese issue with a starting yield of 1.3% equates to a 1.90% price change.

When the more commonly analyzed effects of varying maturities and differing yield changes are added to the impact of different initial yield levels, the resulting changes in relative price movements are not intuitive.

Finally, changes in credit quality can have a dramatic influence on bond prices. Dislocations in credit markets, such as that experienced in Argentina in 2001 or with financial institutions during the 2007–2009 period can significantly shift investor sentiment and highlight underlying structural weaknesses in these instruments. As a result, corporate debt premiums in addition to sovereign spreads are often negatively impacted in these countries.

What Are the Prospects for Currency Gain versus the U.S. Dollar?

Like the stock and bond markets, a number of factors directly affect foreign exchange rates. The common problem faced by forecasters is whether these factors already have been fully discounted in prices and which factor will dominate at any given time. Those factors generally regarded as affecting foreign currency movements include:

1. The balance of payments and prospective changes in that balance

2. Inflation and interest-rate differentials between countries

3. The social and political environment, particularly with regard to the impact on foreign investment

4. Relative changes in monetary policy

5. Central bank intervention in the currency markets

Exchange rate forecasters have had a dismal record. The factors affecting currency movements, the interactions between each factor, and the massive flows in this market make short- and medium-term predictions especially difficult. Based on a 2010 survey conducted by the Bank for International Settlements, average daily turnover in the foreign exchange markets is estimated to be $4.0 trillion, nearly double the level five years earlier. According to the survey, the increase in turnover was driven by greater activity of high-frequency traders, more trading by smaller banks and financial institutions, and the emergence of retail investors.14 Extrapolating trends from this deluge of information and flows is extremely difficult.

KEY POINTS

• International bonds, both dollar-denominated and non-dollar-denominated, represent a significant and growing share of the world’s fixed income markets.

• Dollar-denominated international bonds generally have similar characteristics as domestically issued bonds and respond to similar market factors.

• The potential returns—and risks—are higher in non-dollar-denominated international bonds, which require greater expertise to effectively manage the currency risks unique to global bond investing.

• Dollar-denominated fixed income instruments, which include Eurodollar bonds, Yankee bonds, global bonds, emerging market debt, Reg 144A debt offerings, and Euro Medium Term Notes, have fostered growth in international bond markets.

• The prefix Euro- in international bond markets has come to mean offshore, or debt issues that are marketed outside any domestic jurisdiction in a denomination other than the local currency.

• Non-dollar-denominated debt, including foreign bonds, Eurobonds, and local currency domestic debt, potentially offer greater return opportunities but with additional risk given the exposure to foreign currency.

• The components of return in non-dollar-denominated bonds include income, domestic capital gains, and foreign currency returns.

• The potential investor base for international fixed income assets has broadened as a result of the rapid growth of bond mutual funds which invest abroad (such as emerging market debt funds, global debt funds, and international debt funds) and ETFs dedicated to international bond strategies.

• International bond investors need to consider volatility and potential returns resulting from currency hedged and unhedged portfolios.

• Over shorter time periods, currency volatility and returns dominate international bond portfolio returns, suggesting that hedging such exposure may be beneficial. Over longer time horizons, the income component of fixed income securities exhibits positive returns suggesting that hedging may be unnecessary.