CHAPTER 9

Organizational Structure for Managing Information Assurance

Information assurance is an interdisciplinary and multidepartmental issue requiring commitment from the entire organization. Successful implementation of the IAMS depends on the availability of an organizational structure for managing information assurance. As detailed in Chapter 2, defining roles and responsibilities should be started during the Do phase. Experience has shown that ill-defined structures and ambiguous roles contribute to failures in information assurance management. Defining a “right” structure is the cornerstone for successfully implementing an information assurance program. Thus, it should have the highest priority compared with other controls.

Organizations differ in size, complexity, and culture, and there is no single structure to manage information assurance ideally. This chapter describes the common structures that are applicable to most organizations. The discussion also touches on staffing levels and employee roles and responsibilities; of course, smaller organizations may have the same functions spread across a smaller staff.

Importance of Managing Information Assurance as a Program

The popular phrase “information assurance is a process and not a one-off event” is always true. A continuous improvement process adds to an effective information assurance program. This involves activities such as monitoring the program periodically, measuring performance, evaluating the effectiveness of controls, conducting security audits, and performing risk re-assessments. Organizations have discovered that awareness training, and education (AT&E) programs organized at all levels have improved security significantly.

A good information assurance management program is pervasive; it permeates multiple levels of the enterprise and provides benefits to the organizational culture. Every level enhances the entire organizational security profile by using various types of expertise, authority, and resources. A well-planned information assurance management program produces the following positive results:

• It will have continuous support and commitment from the top management to sustain an effective program by ensuring matters such as required resources are available.

• Employees will be directly involved in the planning of local security systems.

• Executives will have a better understanding of the organization and will be able to effectively play their role and use their authority to protect information.

• Information assets will be securely managed by the organization as per information handling categorization.

• Managers within each of the business and operational units will be more aware and familiar with specific security requirements, including technical and procedural requirements, associated challenges, and risks of the IT environment.

• It will implement secured physical and logical access to IT infrastructure.

Based on the strategy of the organization, the list of positive results may be different, but the general outcomes will be similar. For example, in a top-down approach, the first two items in the list will be more obvious. On the other hand, managers who are aware of specific security requirements may be emphasized in a bottom-up approach.

Refer also to Chapter 8 on various approaches for implementing information assurance.

Structure of an Information Assurance Organization

There are three types of structural options available for consideration.

• Centralized structure where an information assurance management program is managed under a centralized unit with ultimate accountability and responsibility for the program

• Distributed structure where roles, responsibilities, and authorities are spread throughout the organization’s business units, operations areas, and geographical locations

• Hybrid structure that is a mix of the centralized and distributed structures

In attempting to determine the right structure, the nature of business and the size of the organization are important. Usually, the structure is influenced by the organization’s culture, the current business processes, and the IT functions within the organization.

A centralized management program is more suited for smaller organizations that have limited resources and budget. Some examples of activities that should be centralized include the following:

• Defining information assurance roles, responsibilities, and authorities

• Developing IT security architecture

• Developing policies and guidelines

• Organizing an awareness program

• Setting up a computer emergency readiness team (CERT) capability and conducting training for the selected personnel

In contrast, a distributed program management approach may be better suited for complex organizations with multiple locations, international branches, and business units. In a distributed structure, each functional unit (department, division, subsidiary, or business location) is responsible for its own security planning and implementation. In addition, overseas branches may also be subjected to local rules and regulations that would be best managed by the overseas branches themselves. However, some small and mediumsized businesses also operate in a distributed way.

There has been a trend toward the adoption of hybrid structure. The hybrid structure features centralized management of information assurance with decentralized execution of security activities. From a practical perspective, a hybrid structure attempts to avoid redundant tasks and waste of resources. The centralized part promotes uniformity in activities across the organization while the distributed part allows for easier enforcement of policies and internal regulations across the organization.

Information Assurance Staffing

In addition to the basic elements in an information assurance management structure, recruiting and assigning the right personnel to handle information assurance–related jobs are vital tasks. See Chapter 13 on guidelines for recruiting new employees.

Once hired, regularly give all employees appropriate job-related training about IT and information assurance. Competency skill programs are important to nurture talents especially when organizations explore new opportunities in other countries.

Organizations may recruit workers from around the world in accordance with the local labor laws and regulations. However, most laws and regulations do not require newly recruited employees to sign any work ethics or nondisclosure agreements. As a proactive control, new recruits should be required to execute an agreement on ethics and monitoring related to the protection of information during their employment.

Roles and Responsibilities

It is common to find confusion in the organization over responsibility for information assurance. Management should promote awareness that “information assurance is everyone’s responsibility.” This responsibility lies in the hands of the operational team and cuts across the whole organization with the senior management driving the strategy for information assurance initiatives.

A clearly defined structure of the roles and responsibilities for individuals and teams involved in the information assurance management program is essential to ensure effectiveness and smooth operation of the program. Industry has established a generic list of the main groups that an organization should involve in the information assurance management program structure.

• Senior management

• Information assurance units

• Cyber security units

• Privacy units

• Technology and service providers

• Supporting functions

• Users

Each of these groups is discussed in the subsequent sections.

Senior Management

In addition to accepting risk and setting direction, senior management establishes and enforces the organization information assurance program. They endorse and approve policies and objectives supporting the vision and mission of the organization, define and appoint, or change the roles and responsibilities of the appropriate management representatives and the tactical security team members. As an example, the following roles have been adapted from U.S. NIST role definitions. Note that while an organization may not use these exact titles and divisions of responsibility, the organization should consider where the function is performed. Large organizations may be equipped to have unique individuals assigned to each of the roles.

Chief Executive Officer

The chief executive officer (CEO) has the role of being the head of the organization or business.

The head of an organization is the highest-level senior official or executive within an organization and has the overall responsibility to provide information assurance protections commensurate with the risk and magnitude of harm (that is, affect) to organizational operations and assets, individuals, and other organizations, resulting from the unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction of information collected or maintained by or on behalf of the organization and information systems used or operated by an organization or by a contractor of an organization or other entity on behalf of an organization. Organization heads are also responsible for the following:

• Ensuring that information assurance management processes are integrated with strategic and operational planning processes

• Ensuring that senior officials within the organization provide information assurance for the information and information systems that support the operations and assets under their control

• Ensuring that the organization has trained personnel sufficient to assist in complying with the information assurance requirements in related legislation, policies, directives, instructions, standards, and guidelines

Through the development and implementation of strong policies, the CEO establishes the organizational commitment to information assurance and the actions required to effectively manage risk and protect the core missions and business functions being carried out by the organization. The CEO establishes appropriate accountability for information assurance and provides active support and oversight of monitoring and improvement for the information assurance program. Senior leadership commitment to information assurance establishes a level of due diligence within the organization that promotes a climate for mission and business success.

Chief Risk Officer

The chief risk officer (CRO) holds the risk executive functional role in an organization.

The risk executive is a functional role established within organizations to provide a more comprehensive, organization-wide approach to risk management. The risk executive (function) serves as the common risk management resource for senior leaders/executives, mission/business owners, chief information officers, chief information security officers, information system owners, common control providers, enterprise architects, information security architects, information systems/security engineers, information system security managers/officers, and any other stakeholders with a vested interest in the mission/business success of organizations. The risk executive (function) coordinates with senior leaders/executives to do the following:

• Establish risk management roles and responsibilities.

• Develop and implement an organization-wide risk management strategy that guides and informs organizational risk decisions (including how risk is framed, assessed, responded to, and monitored over time).

• Manage threat and vulnerability information with regard to organizational information systems and the environments in which the systems operate.

• Establish organization-wide forums to consider all types and sources of risk (including aggregated risk).

• Determine organizational risk based on the aggregated risk from the operation and use of information systems and the respective environments of operation.

• Provide oversight for the risk management activities carried out by organizations to ensure consistent and effective risk-based decisions.

• Develop a greater understanding of risk with regard to the strategic view of organizations and their integrated operations.

• Establish effective vehicles and serve as a focal point for communicating and sharing risk-related information among key stakeholders internally and externally to organizations.

• Specify the degree of autonomy for subordinate organizations permitted by parent organizations with regard to framing, assessing, responding to, and monitoring risk.

• Promote cooperation and collaboration among accrediting officials to include security accreditation actions requiring shared responsibility (such as joint/leveraged accreditations).

• Ensure that security (risk acceptance) decisions consider all factors necessary for mission and business success.

• Ensure shared responsibility for supporting organizational missions and business functions using external providers receives the needed visibility and is elevated to appropriate decision-making authorities.

• The risk executive (function) requires a mix of skills, expertise, and perspectives to understand the strategic goals and objectives of organizations, organizational missions/business functions, technical possibilities and constraints, and key mandates and guidance that shape organizational operations. To provide this needed mixture, the risk executive (function) should be filled by a single individual or office (supported by an expert staff) and supported by designated groups (such as a risk board, executive steering committee, and executive leadership council).

• Designate the CISO and CSO as independent from the CIO if possible.

The risk executive (function) fits into the organizational governance structure in such a way as to facilitate efficiency and to maximize effectiveness. While the organization-wide scope situates the risk executive (function), its role entails ongoing communications with and oversight of the risk management activities of mission/business owners, accrediting officials, information system owners, common control providers, chief information officers, chief information security officers, information system and security engineers, information system security managers/officers, and operational stakeholders.

Chief Information Officer

The chief information officer (CIO) fills the head information systems and information management role in an organization and decides the organization’s approach to information technology use, adoption, and operational risk management. The function of the CIO is to do the following:

• Designate a senior information security officer to ensure proper implementation of security controls and continuous information assurance risk monitoring. In some organizations, this may take the role of a CISO; however, organizations must be cautious of this reporting relationship since they must have unbiased risk assessments from the CISO.

• Develop and maintain information security policies, procedures, and controls to address all applicable requirements.

• Oversee personnel with significant responsibilities for information security and ensure the personnel are adequately trained.

• Assist senior organizational officials concerning their information assurance responsibilities,

• In coordination with other senior officials such as the CRO, report at least annually to the CEO or board of directors on the overall effectiveness of the organization’s information assurance program, including identified threats and the progress of remedial actions.

The chief information officer, with the support of the CRO and the CISO or CSO, works closely with accrediting officials and their designated representatives to do the following:

• Ensure an organization-wide information assurance program is effectively implemented resulting in adequate assurance for all organizational information systems and environments of operation for those systems.

• Ensure information assurance considerations are integrated into programming/planning/budgeting cycles, enterprise architectures, and acquisition/system development life cycles.

• Ensure information systems are covered by approved security plans and are accredited.

• Ensure information assurance–related activities required across the organization are accomplished in an efficient, cost-effective, and timely manner.

• Ensure there is centralized reporting of appropriate information assurance–related activities.

The chief information officer and accrediting officials determine, based on organizational priorities, the appropriate allocation of resources dedicated to the protection of information systems supporting the organization’s missions and business functions. For selected information systems, designate the chief information officer as an accrediting official or a co-accrediting official with other senior organizational officials.

Chief Information Security Officer

The chief information security officer (CISO) is an organizational official responsible for serving as the primary liaison for the chief information officer to the organization’s accreditation officials, information system owners, common control providers, and information system security officers

The chief information security officer does the following:

• Possesses professional qualifications, including training and experience, required to administer the information security program functions (see Chapter 13 for more information about training and education)

• Maintains information assurance duties as a primary responsibility

• Heads an office with the mission and resources to assist the organization in achieving more secure information and information systems in accordance with the requirements of the organization, its industry, and any legal mandates

The CISO (or supporting staff members) may also serve as accreditation official liaisons or security control assessors. The CISO must be cautious to ensure no conflicts of interest exist between the staff and those being assessed.

Chief Security Officer

When instantiated, the chief security officer (CSO) oversees the following:

• The CISO either directly or through an indirect reporting structure for information assurance related to information systems.

• Physical security controls throughout the organization in coordination with the CISO and CRO. You can find more information about physical security in Chapter 16.

• Personnel security throughout the organization in coordination with HR, the CISO, and the CRO. You can find more for information about personnel security in Chapter 13.

Accrediting Official

Although the accrediting model is not universal, it is used by the U.S. government. The process helps organizations assign accountability for information systems in the assurance process. The accrediting official accepts responsibility for unmitigated risks. The U.S. NIST defines the accrediting official (AO) as a senior official or executive with the authority to formally assume responsibility and risk impacts for operating an information system at an acceptable level of risk to organizational operations and assets, individuals, and other organizations. Accrediting officials must have budgetary oversight for an information system or must be responsible for the mission and/or business operations supported by the system. Through the information assurance accreditation process, accrediting officials are accountable for the information assurance risks associated with information system operations. Accordingly, accreditation officials must be in management positions with a level of authority commensurate with understanding and accepting information system–related security risks.

Accrediting officials also approve system security plans, memorandums of agreement or understanding, and plans of action and milestones to determine whether significant changes in the information systems or environments of operation require re-accreditation. Accreditation officials can deny authorization to operate an information system. Or, if the system is operational, they can halt operations if unacceptable risks exist. Accrediting officials coordinate their activities with the CRO, CIO, CSO, CISO, common control providers, information system owners, information system security officers, security control assessors, and other stakeholders during the information assurance accreditation process.

With the increasing complexity of missions/business processes, partnership arrangements, and the use of external/shared services, it is possible that a particular information system may involve multiple accrediting officials. If so, agreements are established among the accrediting officials and documented in the information system’s security plan. Accreditation officials are responsible for ensuring that all activities and functions associated with security accreditation are carried out. Accreditation officials often designate a liaison with specific information assurance expertise to assist them in their duties.

Accrediting Official Liaison The accrediting official liaison (AOL) is an organizational official who acts on behalf of an AO to coordinate and conduct the required day-to-day activities associated with the information assurance accreditation process. AOLs can be empowered by AOs to make limited decisions about the planning and resourcing of the accreditation process, approval of information system security plans, approval and monitoring the implementation of plans of action and milestones, and the assessment of risk. The AOL may also prepare the final accreditation package, obtain the AO’s signature on the accreditation decision document, and transmit the accreditation package to appropriate organizational officials. The accreditation decision and signing of the associated accreditation decision document may not be delegated to the AOL. In other words, the acceptance of risk to organizational operations and assets, individuals, and other organizations is exclusively that of the AO.

Information Assurance Units

In large organizations, an information assurance unit directs, coordinates, plans, and organizes information assurance activities organization wide. The unit communicates relevant security matters to both internal and external parties as appropriate. The unit works with a variety of individuals, bringing them together to implement controls in response to current and anticipated information assurance risks.

This unit is also in charge of suggesting strategy and taking steps to implement the controls needed to protect both the organization’s information and the information supplied to the organization by external parties. More importantly, it investigates ways that information assurance–related technologies, requirements, processes, and organizational structures are applied to achieve the goals of the organization’s strategic plan.

Information Assurance Control Assessor

The information assurance control assessor (IACA) is an individual, group, or organization responsible for conducting a comprehensive assessment of the management, operational, and technical security controls employed within or inherited by an information system to determine the overall effectiveness of the controls. They asses if controls are implemented correctly, operating as intended, and producing the desired outcome with respect to meeting the security requirements for the system.

Information assurance control assessors also report on the severity of weaknesses or deficiencies discovered in the information system and its environment of operation as well as recommend corrective actions to address identified vulnerabilities. In addition to these responsibilities, information assurance control assessors prepare the final security assessment report containing the results and findings from the assessment. Prior to initiating the security control assessment, an assessor conducts an assessment of the information system security plan to help ensure that the plan provides a set of information assurance controls for the information system that meet the stated assurance requirements.

The required level of assessor independence is determined by the specific conditions of the security control assessment. For example, when the assessment is conducted in support of an accreditation decision or ongoing accreditation, the accrediting official makes an explicit determination of the degree of independence required in accordance with organizational policies, directives, standards, and guidelines. The independence of an assessor is an important factor in the following:

• Preserving the impartial and unbiased nature of the assessment process

• Determining the credibility of the security assessment results

• Ensuring that the accrediting official receives objective information possible to make an informed, risk-based, authorization decision

The information system owner and common control provider rely on the security expertise and the technical judgment of the assessor to do the following:

• Assess the information assurance controls employed within and inherited by the information system using assessment procedures specified in the security assessment plan

• Provide specific recommendations on how to correct weaknesses or deficiencies in the controls and address identified vulnerabilities

The information assurance control assessor is also critical in issuing a certification decision. The assessor should review the required information assurance controls and determine whether the system should be certified in accordance with a defined standard.

Information Assurance Engineer

The information assurance engineer (IAE) is an individual, group, or organization responsible for conducting information system assurance engineering activities. Individuals in this role can be certified by organizations such as (ISC)2 with its examination for the CISSP-ISSEP. Information system assurance engineering is a process that captures and refines information assurance requirements and ensures that the requirements are effectively integrated into information technology component products and information systems through purposeful information assurance architecting, design, development, and configuration. Information assurance engineers are an integral part of the development team (such as the integrated project team), designing and developing organizational information systems or upgrading legacy systems. (You can find more information about secure development and acquisition in Chapter 15.) Information assurance engineers employ best practices when implementing information assurance controls within an information system, including software engineering methodologies, system/security engineering principles, secure design, secure architecture, and secure coding techniques. Information assurance engineers coordinate their security-related activities with information assurance architects, CISOs, CSOs, CROs, information system owners, common control providers, and information system security officers.

Information Assurance Architect

The information assurance architect (IAA) is an individual, group, or organization responsible for ensuring that the information assurance requirements necessary to protect the organization’s core missions and business processes are adequately addressed throughout the enterprise architecture, including reference models, segment and solution architectures, and the resulting information systems supporting those missions and business processes. Individuals in this role can be certified by organizations such as (ISC)2 with its examination for the CISSP-ISSAP. The information assurance architect ideally serves as the liaison between the enterprise architect and the information assurance engineer and also coordinates with information system owners, common control providers, and information system security officers on the allocation of information assurance controls as system-specific, hybrid, or common controls. In addition, information assurance architects, in close coordination with information system security officers, advise accrediting officials, chief information officers, CISOs, CSOs, and the CRO on a range of assurance-related issues including, for example, information system boundaries, assessments of the severity of weaknesses and deficiencies in the information system, plans of action and milestones, risk mitigation approaches, security alerts, and potential adverse effects of identified vulnerabilities.

Information System Security Officer

The information systems security officer (ISSO) is an individual responsible for ensuring that the appropriate operational assurance posture is maintained for an information system and as such works in close collaboration with the information system owner. The information system security officer also serves as a principal advisor on all matters, technical and otherwise, involving the assurance of an information system. The information system security officer has the detailed knowledge and expertise required to manage the assurance aspects of an information system and, in many organizations, is assigned responsibility for the day-to-day information assurance operations of a system such as incident response activities and serving as a liaison for investigations.

This responsibility may also include, but is not limited to, physical and environmental protection, personnel security, incident handling, and information assurance training and awareness. The information system security officer may be called upon to assist in the development of the security policies and procedures and to ensure compliance with those policies and procedures. In close coordination with the information system owner, the information system security officer often plays an active role in the monitoring of a system and its environment of operation, which includes developing and updating the system’s security plan, managing and controlling changes to the system, and assessing the security impact of those changes.

Technology and Service Providers

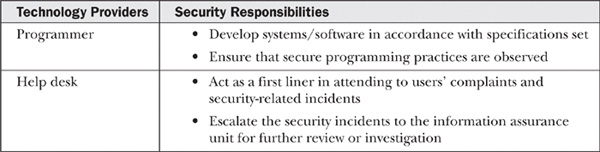

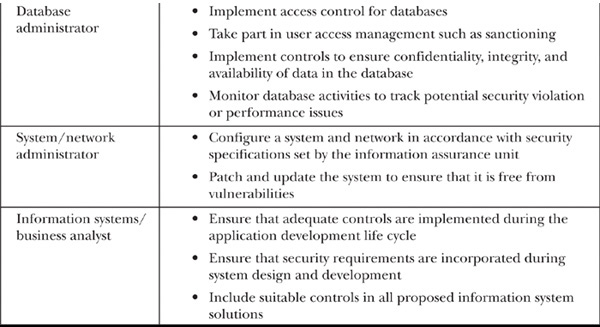

Technology and service providers supply information assurance consultancy, services, and products. Table 9-1 describes the security responsibilities of this group based on the experiences gathered by NIST.

Table 9-1 Responsibilities of Technology and Service Providers

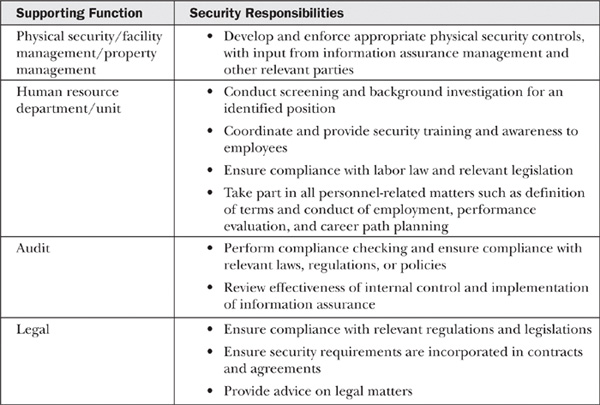

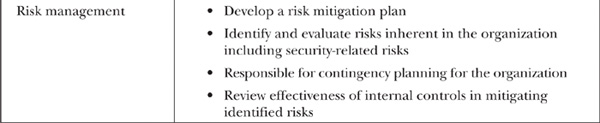

A successful implementation of information assurance requires participation from other supporting functions. The important support functions are summarized in Table 9-2.

Table 9-2 Responsibilities of Supporting Functions

Information System Owner

The information system owner (ISO) is an organizational official responsible for the procurement, development, integration, modification, operation, maintenance, and disposal of an information system.

The information system owner is responsible for addressing the operational interests of the user community (that is, users who require access to the information system to satisfy mission, business, or operational requirements) and for ensuring compliance with information assurance requirements. In coordination with the information system security officer, the information system owner is responsible for the development and maintenance of the system security plan and ensures that the system is deployed and operated in accordance with the agreed-upon information assurance controls. In coordination with the information owner/steward, the information system owner is also responsible for deciding who has access to the system (and with what types of privileges or access rights) and ensures that system users and support personnel receive the requisite information assurance training (such as instruction in the rules of behavior).

Based on guidance from the accrediting official, the information system owner informs appropriate organizational officials of the need to conduct the information assurance accreditation, ensures that the necessary resources are available for the effort, and provides the required information system access, information, and documentation to the information assurance control assessor. The information system owner receives the information assurance assessment results from the security control assessor. After taking appropriate steps to reduce or eliminate vulnerabilities, the information system owner assembles the accreditation package and submits the package to the accrediting official for adjudication.

Common Control Provider

The common control provider (CCP) is an individual, group, or organization responsible for the development, implementation, assessment, and monitoring of common controls (that is, information assurance controls inherited by information systems).

Common control providers are responsible for the following:

• Documenting the organization-identified common controls in a system security plan (or equivalent document prescribed by the organization)

• Ensuring that required assessments of common controls are carried out by qualified assessors with an appropriate level of independence defined by the organization

• Documenting assessment findings in an information assurance assessment report and producing a plan of action and milestones for controls having weaknesses or deficiencies

System security plans, information assurance assessment reports, and plans of action and milestones for common controls (or a summary of such information) are made available to information system owners inheriting controls from the common control provider. The control information is released to the information system owners after the information is reviewed and approved by the senior official or executive with oversight responsibility for those controls.

Users

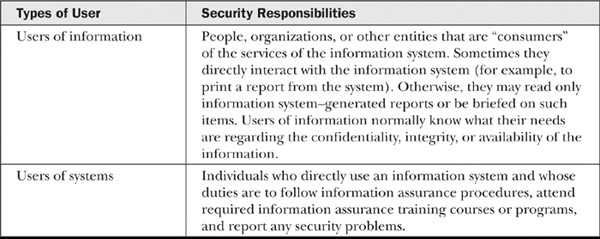

Users play a significant role and a specific responsibility for implementing information assurance. Again, based on the experiences gathered by NIST, the two types of users and their relevant responsibilities are described in Table 9-3.

Table 9-3 Responsibilities of Users

Information Owner/Steward

The information owner/steward is an organizational official with statutory, management, or operational authority for specified information and the responsibility for establishing the policies and procedures governing its generation, collection, processing, dissemination, and disposal.

In information-sharing environments, the information owner/steward is responsible for establishing the rules for appropriate use and protection of the subject information (that is, the rules of behavior) and retains that responsibility even when the information is shared with or provided to other organizations. The owner/steward of the information processed, stored, or transmitted by an information system may or may not be the same as the system owner. A single information system may contain information from multiple information owners/stewards. Information owners/stewards provide input to information system owners regarding the information assurance requirements and information assurance controls for the systems where the information is processed, stored, or transmitted.

Organizational Maturity

![]()

Organizational maturity is important in determining an effective information assurance program. Organizational maturity is a reflection of how well an organization manages internal processes, changes, and responses to unexpected events. Several organizational maturity models exist depending on industry. Some of the more common are as follows:

• Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL)

• Capability Maturity Model (CMM)

• Organizational Change Maturity Model (OCMM)

Information Technology Infrastructure Library

Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) is a service delivery specific model. ITIL was initially developed by the United Kingdom’s Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency in the 1980s. It was designed to bring order and control around a growing reliance on information technology in government business. Today, ITIL consists of several volumes covering the following areas of service delivery:

• Service strategy

• Service design

• Service transition

• Service operation

• Continual service improvement

ITIL addresses information assurance through the reference of the ISO 27000 series. ITIL requires information assurance through organizational governance and alignment with organizational goals. Information assurance is included in the Service Design and the Service Operation sections of the ITIL framework. Information assurance should also be part of continual service improvement because information assurance controls can enhance service delivery, transition, and operation. As organizations progress from low levels of maturity, incidents and unplanned events become less, and the ability of the organization to react and learn from unplanned events becomes greater.

Capability Maturity Model

CMM precedes another maturity model called the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI). While CMM looks at organizational maturity, CMMI focuses on software development processes. CMM reviews the processes, practices, and behaviors of an organization and assigns one of the following levels of maturity:

• Initial Most if not all processes are not documented, and there is little if any performance measures and planning. Organizations at this level are often called chaotic or unstable and tend to be reactive in not only general operations but also information assurance.

• Repeatable Organizations at this level of maturity have developed repeatable processes and practices that yield consistent results. Information assurance processes may be some of the processes that are repeatable.

• Defined Processes are documented and defined throughout the organization. Standard processes have been identified and documented and are operating with limited improvement. In times of duress, these procedures are likely to be circumvented.

• Managed The processes of an organization are defined, documented, and measured. Measuring allows the organization to determine whether a process is suitable for a project it may not be currently used in.

• Optimizing Processes are defined, documented, measured, and constantly evaluated for improvements through people, technology, or complementary processes. This stage often uses statistical analysis as part of the process improvement.

CMM does not explicitly mention information assurance or its subdisciplines; however, organizations can use the model to measure the maturity of information assurance programs. Information assurance programs rely on people, processes, and technology. The processes can be subject to a CMM review and progression through maturity.

Organizational Change Maturity Model

The Organizational Change Maturity Model (OCMM) is another derivative of the CMM model. The OCMM focuses on change management throughout an organization. As noted in Chapters 14 and 15, managing change with an integrated information assurance program is crucial for managing risk. One of the few constants an organization has is change. Change can represent opportunities and competitive advantage if managed correctly. It can also represent catastrophic failure and information assurance problems. A vast majority of information assurance–related vulnerabilities result from poorly planned and executed change management efforts. New servers deployed without hardened configurations or entering into cloud agreements without involvement of the information assurance program are examples of changes leading to increased risk.

Outsourcing and Cloud Computing

![]()

The previous section discusses some of the areas of concern for the internal management of information assurance.

Outsourcing information assurance management is gradually becoming the norm. This trend is driven by several factors including economic, the rapid increase in the number of information security incidents, and the complexity of information assurance issues. It is important for organizations to understand issues related to outsourcing before actually deciding to engage in such an arrangement. The following are among some of the challenges faced:

• Loss of control An outsourcer would prefer greater control since it makes it harder for organizations to terminate services provided. As a result, an organization may become too reliant on service providers. Of course, without their aid, the organization may suffer from serious failures that affect daily operations.

• Sensitive information The company wants to protect sensitive information from inappropriate misuse and disclosure.

• Quality of service Outsourcers generally work based on the stipulated scope of work and service level agreement. Unlike internal employees, outsourcers would not be responsible for additional or ad hoc job requests unless paid.

• Viability of service providers to supply the agreed services Mismanagement, inadequate funding, merging, and acquisitions are possible factors that could lead to a discontinuation of services.

Outsourcing information assurance is not appropriate for every organization. Some organizations will be better off implementing, managing, and monitoring information assurance management internally. It is important that an organization establish expectations before approaching an information assurance outsourcing arrangement. Basing outsourcing decisions on an analysis of the information assurance risks involved, the required resources and capabilities, current operational capabilities and costs, and the overall business objectives is essential. Remember, the organization outsourced to will never understand the mission or business like an employee will.

An organization deciding to outsource their information assurance should consider the following:

• Maintain security control Organizations should be aware that once an outsourcing service is used, including cloud services, the service provider’s employees might have direct access to and control of their information assets. Thus, a service contract and a service level agreement (SLA) should be established that clearly spell out how information assurance is to be managed (ISO/IEC 17799 provides a list of the items to be considered in producing a contract and SLA). These include issues such as what information may be accessed and performing background checks of the provider’s employees. In addition, perform regular audits so that the provider is always adhering to the terms of the agreement.

• Perform due diligence Before awarding an outsourcing contract, organizations should have processes in place to perform due diligence checks, such as checking the facts and credentials of the service provider. Do this by checking with current or past clients of the vendors as well as an organization such as Dunn and Bradstreet. In cases where the provider is outside of an organization’s home country, organizations should consider hiring legal services in the outsourcing country to check on the status of the provider and examine provisions in the contract to see whether they will be legally enforceable in the provider’s jurisdiction.

• Audit processes and facilities prior to signing an agreement and regularly thereafter Trust is undoubtedly important when choosing a service provider. Conduct independent audits on the quality of the provider’s information assurance management processes at least twice a year and certainly before agreeing to do business with them. Note that it is easier to establish audits before signing a contract than afterward. Tour the buildings where the work is performed to ensure that they are physically secure, and review existing evidence of security compliance or breaches to ensure risk is acceptable to your organization.

Further Reading

• An Introduction to Computer Security: The NIST Handbook (Special Publication 800-12). NIST, 1996.

• Information Government Toolkit. Information Security Assurance – Social Care Guidance. National Health Service (NHS). United Kingdom, June 16, 2007. https://www.igt.connectingforhealth.nhs.uk/guidance/IS_Sc_310_V5%2007-04-27.doc.

• Information Technology – Security Techniques – Code of Practice for Information Security Management (ISO/IEC 17799), ISO/IecIEC.

• Ross, R., et al. Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems (Special Publication 800-53). NIST, 2005.

• Schou, Corey D., and D.P. Shoemaker. Information Assurance for the Enterprise: A Roadmap to Information Security. McGraw-Hill Education, 2007.

• Tipton, Harold F., and S. Hernandez, ed. Official (ISC)2 Guide to the CISSP CBK 3rd edition. ((ISC)2) Press, 2012.

• Wood, Charles C. Information Security Roles & Responsibilities Made Easy. PentaSafe Security Technologies, 2002.

Critical Thinking Exercises

1. An organization is thinking about moving its core infrastructure into the cloud. It makes extremely good financial sense. What actions must a prudent executive or senior leader take to ensure the financial windfall isn’t caused by security shortcomings?

2. An organization is thinking of collaborating with another to perform some data processing. Your organization has a top-down centralized approach to information assurance while it seems the organization you want to collaborate with has a bottom-up decentralized approach to security. Should you be concerned about this difference in cultures?