CHAPTER 15

Transform Your Operating Model

With David Toth*

“So much of what we call management consists of making it difficult for people to work.”

—PETER DRUCKER

It seemed like nothing would make a dent against a dismal situation. The $4 billion company in question had missed its growth objectives over the previous several years, and had only met its earnings targets a few of the preceding quarters. In response, the business had taken action. It had launched restructuring initiatives, creating a global supply chain function and deploying a global sales structure. It announced in year-end presentations a number of programs to focus on key business issues: reducing rising SG&A costs, improving working capital, and getting pricing right. In fact, it announced the same programs, on the same issues, eight years in a row. Nothing made a dent.

And nothing would, until it changed its operating model. Despite being a large company by revenue, the business was actually subscale. It had fragmented itself and was, in fact, really a hundred small businesses, each with its own metrics, P&L, and focus on local optimization. Despite having moved toward global functional and product leadership roles, in reality leaders operated with limited decision-making authority, capital, and capacity. All the underlying organizations, processes, policies, and technologies were still local, independent, and different. The complexity of the operating model and resulting ambiguity in accountability kept them from realizing significant bottom line and working capital benefits while making it difficult to grow and scale the business effectively throughout market cycles.

No wonder their initiatives floundered. In the face of more than 10,000 price lists, and little in the way of controls, any pricing optimization effort would fail. Rationalizing the portfolio, to make headway against the more than 1 million SKUs the business carried, would require getting more than 500 stakeholders to agree!

It seems like madness, but the company’s operating model was rooted in a belief in local entrepreneurship. Years back, this belief had helped the business grow and flourish by being customer-responsive. But the business had evolved in the years since in ways no one had predicted. It was a model that had made sense at an earlier stage in its journey, but was counterproductive today.

And that is the point: the right operating model for your business will change as conditions change. Yet many businesses operate with the same operating model they had 10, 20, even 100 years ago! Conditions have changed, so the time to reinvent is now. Knowing when to embark on a reinvention of your operating model (the triggers), as well as how (the road map) are critical elements in the Navigator’s Skill Set, as waiting too long can put you at significant competitive disadvantage, and too many operating model initiatives get downgraded to moving names around on an organizational chart.

In this chapter, we’ll define what an operating model is, discuss how models become outdated, and highlight a road map for transformation.

Understanding Operating Models

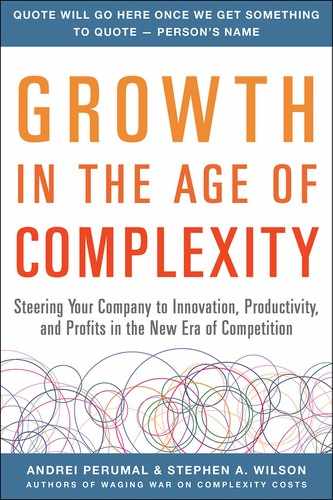

A company’s operating model provides the critical link between its market strategy and the execution of that market strategy (see Figure 15.1). It defines how the company organizes and aligns decision making, assets, and operations to deliver value to its customers. An operating model therefore acts as both the foundation for a company’s strategy and the framework for its execution. It addresses the questions of who does what, where it is done, how best to deploy assets, and how to make decisions. Just as companies cannot overcome poor execution with a well-designed operating model, they also cannot overcome poor structures and governance with great execution.

FIGURE 15.1: A Good Operating Model Impacts Strategy and Execution

There are six components that comprise an operating model:

![]() Governance. Where and how operating decisions are made and, ultimately, how the business will be aligned on a product, geographic, and functional basis; establishes the role of the corporate center; clarifies policy and process ownership.

Governance. Where and how operating decisions are made and, ultimately, how the business will be aligned on a product, geographic, and functional basis; establishes the role of the corporate center; clarifies policy and process ownership.

![]() Assets and capabilities. Identification and deployment of company facilities and equipment, including offices, factories/plants, tooling, warehouses, and research labs, owned or leased; can also be the patents and intellectual property used to generate revenue or uniquely manage operations; may include data and certain competencies.

Assets and capabilities. Identification and deployment of company facilities and equipment, including offices, factories/plants, tooling, warehouses, and research labs, owned or leased; can also be the patents and intellectual property used to generate revenue or uniquely manage operations; may include data and certain competencies.

![]() Partners. Where and for what the company will rely on those outside the organization to provide; front office and operations partner roles; back office outsourcing alternatives.

Partners. Where and for what the company will rely on those outside the organization to provide; front office and operations partner roles; back office outsourcing alternatives.

![]() Process design. How the business will execute both value-chain and management processes on an ongoing basis; extent to which processes will be standardized across the business; expected process performance metrics and targets (e.g., cycle time).

Process design. How the business will execute both value-chain and management processes on an ongoing basis; extent to which processes will be standardized across the business; expected process performance metrics and targets (e.g., cycle time).

![]() Organization structure.* Operating and reporting structures needed to deliver strategic and operational objectives with the chosen governance structure; group and/or department organization designs based on business volumes and specific competency needs; roles, spans of control, and alignment of titles; relationships and metrics within and between organizations.

Organization structure.* Operating and reporting structures needed to deliver strategic and operational objectives with the chosen governance structure; group and/or department organization designs based on business volumes and specific competency needs; roles, spans of control, and alignment of titles; relationships and metrics within and between organizations.

![]() Technology. Infrastructure, application, and data architectures employed to support decision making, operations, and compliance; considers where and how the business will need to change and scale over time.

Technology. Infrastructure, application, and data architectures employed to support decision making, operations, and compliance; considers where and how the business will need to change and scale over time.

While each of the elements of an operating model address specific aspects of a company’s structure and decision-making approach, what is most critical is how they fit together. For example, designing an organizational structure without considering how and where assets are best located may lead to customer responsiveness issues or inefficiencies. We recently worked with a banking client that had created a new organization in London to centralize operations. Yet the company had some crucial assets—including data and analytical competency, and prime clients—located in Asia. The result was a large, centralized organization struggling to support customers amid high levels of process inefficiency and back-and-forth across continents and time zones.

Getting operating model decisions right unlocks the power of a strategy. Getting them wrong—or living with an outmoded operating model—is like a lead weight pulling you to the bottom of the sea. Said one SVP of a software company: “We languished for quite some time because we weren’t structured in a way that allowed for us to implement a new strategy.”

How Operating Models Become Outmoded

Part of the reason that organizations often languish with old operating models is because it can take time to realize the problem. If a particular operating model served you well at one point, it’s probably not high on the list of suspects when performance starts to suffer.

Operating models become outmoded in a few key ways. It starts to happen as a company responds to new opportunities and conditions, but in an incremental fashion. Over time, the operating model slowly becomes ill-suited and stretched, which creates execution, cost, and ultimately growth issues. It is akin to building a house one room at a time versus starting with an architectural blueprint.

This happens via organic growth, as a company launches new products, enters new segments and channels, or pursues new customer adjacencies. While revenue may increase, the operating model impact to deliver this new revenue is often hidden, and costs rise unexpectedly. As an example, we worked with a client that made its money delivering large bulk products across the country, and had set up its supply chain and distribution system accordingly: full truckloads, going point-to-point. Over time, it added many new niche products, with plants innovating to customer needs. The mix shifted, and the distribution system “evolved”: partial truckloads became the norm given the product variety, and products were making two, three, or four stops along the way. The assets, organizations, processes, and technologies designed for high volume and low variety became expensive and slow for low-volume, high-variety product types.

The misalignment can also occur through acquisitions. As unique cultures, processes, organizational units, technologies, and systems of governance are merged together, there is typically a period of transition. The endpoint for postmerger integration is typically defined as when the expected synergy savings have been met. Such savings are commonly from a reduction in staff and offices, rationalization of products and closure of plants, and consolidation of direct and indirect spend. However, these cost reductions are not a real indicator of integration. In our experience, there are often legacy ways of working that remain long after the designated transition period, leading to redundancy, ambiguity, and latency in the business.

But perhaps worse is when an operating model stands still, when it fails to keep up with the changing marketplace and is now no longer fit-for-purpose—when your Castle Walls are high. For example, you are a retailer but have never developed an integrated online capability; or when you have built your business and value proposition around offering breadth when what customers really want are a few items, quickly, reliably, and cheaply. When your current structure has been left behind by the industry and competitive landscape, the need to reinvent your operating model becomes urgent.

A Redesign Road Map

When redesigning your operating model, the first point is to understand that while several archetypes typically exist within industries, there is no single blueprint that applies to every company. Even within the same industry, if strategy, value proposition, offerings, asset-base, or capabilities differ, operating models can and should differ as well.

But while operating models should be different, all organizations (and the businesses or functions within) can follow the same design journey: a structured approach, rooted in a thorough understanding of current business context, which is aligned to your strategy and designed to meet specific financial and operational performance targets.

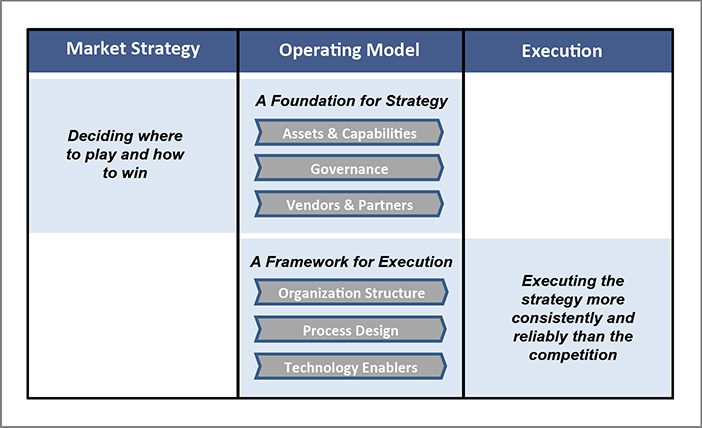

There are many factors that go into redesigning an operating model, as shown in Figure 15.2. Certainly you need a crisp understanding of the current state operating model. Laying this out explicitly can reveal shortcomings and also provides a basis for the change journey. You need a strong understanding of the target performance that the new operating model needs to deliver. We find it helpful to translate this into operational metrics. And all of this needs to be undertaken and influenced in the context of your business strategy and industry dynamics.

FIGURE 15.2: Inputs to Operating Model Redesign

The path forward, at either the business or functional level, will often follow a similar three-phased approach:

Phase 1: Align on the vision and analyze the current state.

Phase 2: Outline the new model and governance approach.

Phase 3: Complete the design in detail and plan for deployment.

Here is more detail on each of these phases.

Phase 1: Align on the Vision and Analyze the Current State

![]() Align on the vision and principles that will guide design decisions down the line.

Align on the vision and principles that will guide design decisions down the line.

![]() Define or refine the expected strategic, financial, and then operational targets to be met.

Define or refine the expected strategic, financial, and then operational targets to be met.

![]() Understand where and why change is needed (front office, back office, operations).

Understand where and why change is needed (front office, back office, operations).

![]() Consider eventual deployment strategy and approaches.

Consider eventual deployment strategy and approaches.

This first step sets the table for the operating model redesign. It starts at the top of the organization. Operating model design efforts require a top-down approach in order to ensure decisions align to the highest priorities of the organization and to effectively distribute and cascade the design effort. Going through the exercise of establishing guiding principles paints a clear picture for the organization, which serves as a common reference point and aligns the executive team from the start.

Next, translating strategic objectives into operational targets provides the organization with clear design parameters and definition of success. For example, consider a company whose growth strategy is centered on new product development. The business will establish specific targets for time-to-market and percent of revenue from new products, which will help product management and development teams from the very beginning as they consider how to align and organize based on product, competency, and/or geographic dimensions.

During this time, clearly understanding current profitability and performance is paramount. For example, a successful engineered-product company was looking to update its operating model, particularly in the front office, to drive growth. The business had one sales force and three product segments serving the construction industry. The initial design assumption was to simply streamline the operating model and continue to take advantage of cross-selling opportunities. But after analysis to establish baseline performance, we determined that only 1 percent of customers actually purchased from all three of the company’s segments, and only another 10 percent purchased across two segments—so 89 percent of its customer base purchased within just one product segment, and would not benefit from extensive work to take advantage of cross-selling. We also discovered, contrary to expectations, that its sales through distribution were on average larger and more profitable than its direct sales, yet there was no formal or centralized distribution management function.

This period of analysis redefined the shape of the company’s operating model. What was going to be an effort to streamline turned into full-scale reengineering—with the realignment of the sales force by product segment, defining new territories, and the introduction of a new organization to formalize and drive distribution sales.

Phase 2: Outline the New Model and Governance Approach

![]() Define the role of the corporate center.

Define the role of the corporate center.

![]() Determine and agree on the proper roles of the front office, back office, and operations.

Determine and agree on the proper roles of the front office, back office, and operations.

![]() Define specific gaps and capability needs at the functional levels.

Define specific gaps and capability needs at the functional levels.

![]() Assess cross–value stream impact.

Assess cross–value stream impact.

![]() Gain a sense of magnitude of change and subsequent deployment challenges.

Gain a sense of magnitude of change and subsequent deployment challenges.

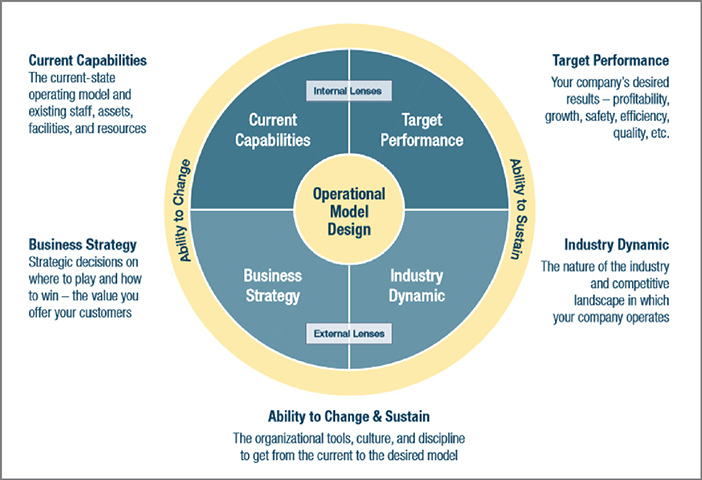

In this phase the needed operating model changes begin to take shape (Figure 15.3). Again, it starts at the top, gaining alignment on the scope and the role of the corporate center (Step 2.1). Will the “corporate” layer be thin, dictating targets but with responsibility otherwise distributed in business units and geographies? Or will the corporate center be much more participatory with functional leadership and support staff along with clear accountability and responsibility for results across the business? With this highest-level decision of scope clear, functions in the front office, back office, and operations can then begin aligning on the best way to govern, deploy assets, and use partners.

FIGURE 15.3: Process-Capability Mapping and Evaluation to Assess Value-Stream Impacts

A critical but frequently missed step in this phase is to step back and understand how key cross-functional value streams will be impacted. Ultimately, overall company performance is driven by how these value streams—order-to-cash, time-to-market, issue-to-resolution, to name a few—perform on an ongoing basis. In helping a natural gas company take this step, we looked at how the order-to-install process would be affected by the decision to go with a single field force managed according to geography. What we found was that “managing by geography” would create significant complexity and require significant new technology investment to maintain effective wrench-time. So instead, the business decided to organize the field force first by customer segment, and then by geography. As in this example, this step may require some rework, but it is essential to take before moving on.

At the end of this phase, the magnitude of change required becomes clear, and the business can consider how best to deploy the downstream changes being assessed, given the organization has limited capacity and resources for change.

Phase 3: Complete the Design in Detail and the Plan for Deployment

![]() Align process, organization, and technology in each functional area.

Align process, organization, and technology in each functional area.

![]() Understand new roles, staffing levels, and competency requirements.

Understand new roles, staffing levels, and competency requirements.

![]() Identify technology gaps and/or alternatives to support.

Identify technology gaps and/or alternatives to support.

![]() Align functional and organization metrics to previously defined targets.

Align functional and organization metrics to previously defined targets.

![]() Reassess and align on the size-of-prize and investment requirements across the effort.

Reassess and align on the size-of-prize and investment requirements across the effort.

![]() Build the detailed implementation road map.

Build the detailed implementation road map.

In this phase, the design work is finally down to the department level within functions. This step only makes sense after the alignment approach, asset deployment strategy, and role of external partners (outsourcing) is decided. At this point detailed organization design takes place and organization charts are produced with titles and names.

Too often, though, we find operating model projects that have started with this step, a definite sign that the organization didn’t really understand what was entailed in an operating model transformation and why the subsequent changes yielded insignificant or even dilutive results. By not recognizing and addressing all six components of an operating model, reorganizing can’t really deliver transformational change.

Case Study: Making the Leap from Multilocal to Global

TMF Group is a multinational professional services firm headquartered in Amsterdam that provides accounting, tax, HR, payroll services, and provision of corporate compliance to businesses operating internationally. It became multinational via more than 50 acquisitions over the last 29 years. In fact, Alejandro Peñas, head of group operations, described its acquisition activity as a “non-stop machine.” Today it has more than 100 offices operating in more than 80 countries.

“We would buy a business in a country where we were not operating before,” Peñas said. “We would not turn that business onto a standard, as at that time we didn’t have a common operating model.” The result, he said, was a network of offices, each working in a slightly different way, each offering services to clients in slightly different ways.

This created some challenges, both operational and strategic, said Peñas, who was given the challenge of reshaping TMF’s operating model. Operationally, with different roles, systems, processes, and standards, the network led to inefficiency and higher operating costs. Strategically, the network undermined what was otherwise a growing value proposition for multinational clients, where more and more contracts were served by multiple offices, and those clients needed TMF to operate consistently across those offices.

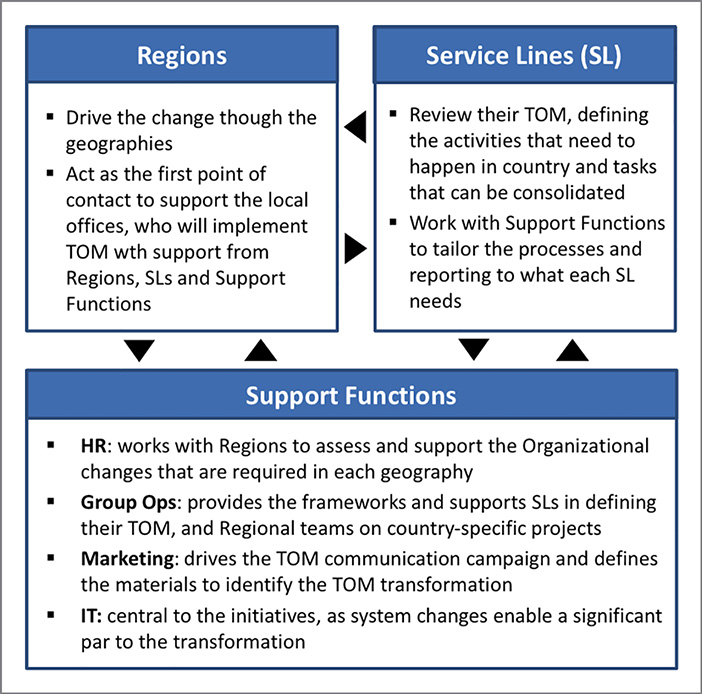

So TMF embarked on reinventing its operating model and established a structure for driving the change (see Figure 15.4). Then it defined the elements of its operating model and how each element was to be approached. The components that it defined were as follows:

FIGURE 15.4: How TMF Organized to Implement Its Target Operating Model (TOM)

![]() Organizational construct: the roles and structure within each office

Organizational construct: the roles and structure within each office

![]() Governance: the key performance indicators (KPIs) used to measure the performance of offices and the ways different layers of the organization interact

Governance: the key performance indicators (KPIs) used to measure the performance of offices and the ways different layers of the organization interact

![]() Processes, procedures, and operating standards: the internal operating policies of offices in different functional areas, such as accounting or payroll

Processes, procedures, and operating standards: the internal operating policies of offices in different functional areas, such as accounting or payroll

![]() Systems: the technical systems that underlie different functions within offices

Systems: the technical systems that underlie different functions within offices

The organizational construct of the offices was the first element it tackled, believing that aligning the roles and structure within each office would make other operating model changes flow more smoothly. It began by looking at the biggest offices to identify good practices that could be replicated. The goal was to create a set of guidelines on the roles and structure within an office that best supported TMF in serving its customers. For example, one such guideline was that every country should have a managing director, and the delivery team should be organized in “units” under team leaders. For other roles, there was a clear need for flexibility. For example, not all offices needed a local salesperson. Some countries had more inbound sales, and others more outbound.

Midway through this effort, after seeing very little traction, the team realized that they needed to look at a wider variety of offices to capture different business situations. The first draft of guidelines for the operating construct didn’t inspire much change within the organization because the team had looked at too few offices and as a result came up with a design that was too narrow. After so many years of operating relatively independently, the offices had a large degree of variety that needed to be accounted for within the recommendations. Peñas noted that finding a solution that seemed workable to a large number of the offices was more important than finding the perfect solution. “If it’s something that the people in the business are happy with, it’s much more valuable than the ‘perfect’ design that remains a PowerPoint slide.”

Sponsorship was another factor that made the revised set of guidelines more successful. As Peñas’ team began iterating on the guidelines, they got buy-in from the head of EMEA, who then became a partner for driving change. The implementation in Europe went ahead and created a reference for others to follow.

Next the team addressed governance, which ended up being a simpler effort. They collaborated with the leadership team to define what KPIs would be used and built reports for those KPIs that were rolled out across the organization. Having already aligned the leadership roles within each office made the rollout of these standards simpler. Creating these KPIs for TMF set the stage for a successful operating model initiative by clarifying, across the organization, what was being measured and what success looked like.

The last piece the operating model transformation addressed was the processes, procedures, and supporting systems within the offices. TMF operates three major service lines: accounting and tax, human resources and payroll, and corporate secretarial. Each of these required unique processes, procedures, and systems, and each was shaped by the ad hoc nature of growth. TMF addressed these a few at a time, focusing on the areas that offered greatest opportunity based on leadership teams’ willingness to partner, known organizational challenges, and clear financial opportunity.

Quantifying the impact is difficult, but TMF group estimates that so far the operating model work has had an impact of about 5 percent of EBITDA for the organization overall, with local office impact ranging from 2 to 3 percent to 10 percent depending on the size and maturity of the office. On top of the financial measures, Peñas said, there have been other benefits as well, such as risk mitigation, client retention, and business continuity.

And lessons learned? Peñas top two are: First, remember that perfect is the enemy of good. “Every operating model needs some flexibility. Differentiate between what must be aligned, and where there are options.” Second, be prepared to spend a lot of time communicating and ensure sufficient input is captured from the bottom of the organization. When moving to a global operating model, sponsorship is critical at all levels. Peñas invested the time to attend regional conferences and built relationships with the managing directors. He listened to their experiences and explained what his team was working on, which made an enormous difference in facilitating a speedy implementation.

Triggers for Operating Model Redesign

It is not uncommon to pin the blame for poor performance on issues other than an out-of-date operating model. Therefore, the ability to understand and pinpoint the triggers that warrant a rethink of how you structure is a valuable part of the Navigator’s Skill Set. With that in mind, we have collected below some of the typical triggers for operating model redesign—the sets of circumstances under which we would recommend that an organization at least assess the value of taking this on:

![]() You’ve been moving from local (or multilocal) to global. For TMF, a global operating model was central to unlocking its global support strategy for its clients. Companies frequently expand overseas in the pursuit of new revenues—the Greener Pasture Siren—and as they do, tend to do so in an incremental, country-by-country manner. Before you know it, you may have replicated costs and infrastructure across many new territories, but not fundamentally adapted your processes. The result: an expensive and inefficient operating model.

You’ve been moving from local (or multilocal) to global. For TMF, a global operating model was central to unlocking its global support strategy for its clients. Companies frequently expand overseas in the pursuit of new revenues—the Greener Pasture Siren—and as they do, tend to do so in an incremental, country-by-country manner. Before you know it, you may have replicated costs and infrastructure across many new territories, but not fundamentally adapted your processes. The result: an expensive and inefficient operating model.

![]() There’s been a significant shift in your value proposition and/or product mix. As markets shift and products go through their life cycle, it’s natural to see a company’s product mix shift, even as the operating model typically stays relatively unchanged. For example, consolidating, centralizing, and standardizing processes for a set of customers who demand quick response and high touch may not make sense and could create in the end significant process complexity as the business struggles with the many nonstandard requests. In contrast, having a highly dispersed, field-based organization in a market that is more cost-focused may create a structural hurdle that is hard to overcome even with the best processes and technology. Of course, it is not uncommon for a product or service to begin life as one (consultative sale) only to migrate to the other (transactional sale) over time.

There’s been a significant shift in your value proposition and/or product mix. As markets shift and products go through their life cycle, it’s natural to see a company’s product mix shift, even as the operating model typically stays relatively unchanged. For example, consolidating, centralizing, and standardizing processes for a set of customers who demand quick response and high touch may not make sense and could create in the end significant process complexity as the business struggles with the many nonstandard requests. In contrast, having a highly dispersed, field-based organization in a market that is more cost-focused may create a structural hurdle that is hard to overcome even with the best processes and technology. Of course, it is not uncommon for a product or service to begin life as one (consultative sale) only to migrate to the other (transactional sale) over time.

![]() New channels have become a bigger factor for your business. An online presence has become a central plank for most retailers’ strategy over the last 15 years. But how to bring this to reality has been a thorny question. In the early days, it was not uncommon to have a separate e-commerce team lurking in a back office somewhere. Over time the need to integrate critical customer touchpoints, supply chain, and stock management across offline and online channels became evident. But what is becoming clear to retailers—and indeed to all businesses looking to digital channels—is that this requires a fundamental rethinking of the operating model. It can’t simply be a “bolt-on.”

New channels have become a bigger factor for your business. An online presence has become a central plank for most retailers’ strategy over the last 15 years. But how to bring this to reality has been a thorny question. In the early days, it was not uncommon to have a separate e-commerce team lurking in a back office somewhere. Over time the need to integrate critical customer touchpoints, supply chain, and stock management across offline and online channels became evident. But what is becoming clear to retailers—and indeed to all businesses looking to digital channels—is that this requires a fundamental rethinking of the operating model. It can’t simply be a “bolt-on.”

![]() You are making acquisitions. In one of our reports, we showed that there was a big difference in performance between occasional acquirers and serial acquirers.1 Part of the difference lies in whether or not you have a scalable operating model that can quickly integrate and absorb new businesses. Companies frequently underestimate the additional complexity that accompanies an acquisition. As companies seek growth outside the core, this phenomenon increases. However, even with acquisitions of similar core-related companies, operating models may require adjustments as incremental products and services and new customers in different geographies strain the current processes and organization.

You are making acquisitions. In one of our reports, we showed that there was a big difference in performance between occasional acquirers and serial acquirers.1 Part of the difference lies in whether or not you have a scalable operating model that can quickly integrate and absorb new businesses. Companies frequently underestimate the additional complexity that accompanies an acquisition. As companies seek growth outside the core, this phenomenon increases. However, even with acquisitions of similar core-related companies, operating models may require adjustments as incremental products and services and new customers in different geographies strain the current processes and organization.

![]() Your business has grown significantly in the last few years. In pursuit of growth, many companies open the door to new organizational add-ons, and new processes, locations, and technology. Decision-making responsibility becomes loose and distributed to preserve local speed. The way you make decisions and structure the business at $100 million is different from the one you need at $500 million, let alone $1 billion. If you’ve seen a significant uptick in growth in the last few years, congratulations. But if your profitability hasn’t grown at the same pace, look at your operating model.

Your business has grown significantly in the last few years. In pursuit of growth, many companies open the door to new organizational add-ons, and new processes, locations, and technology. Decision-making responsibility becomes loose and distributed to preserve local speed. The way you make decisions and structure the business at $100 million is different from the one you need at $500 million, let alone $1 billion. If you’ve seen a significant uptick in growth in the last few years, congratulations. But if your profitability hasn’t grown at the same pace, look at your operating model.

Of course, any significant shift in strategy and competitive conditions should trigger an operating model review. But these developments often announce themselves more forcefully and therefore get the attention required. Macroeconomic shifts and regulatory changes can also trigger the same. And anytime you are pursuing new adjacency opportunities, an operating model review is warranted, as many times these can create far more operational complexity than anticipated. (These and other pitfalls are the subject of the next chapter.)

As TMF demonstrates, reinventing your operating model is not a small thing, but given the number of transformations and major initiatives a business typically undertakes in a two-year period, it is something you should not shy away from. Moreover, as we’ve indicated in this chapter, it can frequently act as a keystone, unlocking the value of a strategy or emerging market opportunity.

* David Toth is a partner with Wilson Perumal & Company, Inc. and supports much of WP&C’s operating model and process transformation work. Prior to joining WP&C, David worked with the firm’s founders at George Group Consulting. Before that, David split his time between industry, consulting, and a start-up in various leadership roles. David received both his MS and BS degrees in industrial engineering from Purdue University.

* When people think about operating models they frequently jump to organizational structure, with reorgs becoming focused on putting different names in boxes on the org chart. However, this is just one element of the operating model and frequently not what makes the biggest difference in changing how people work.