6. Student Loans

Americans now owe more in student loans than they do on their credit cards, and the horror stories of people who overdosed on education debt are legion. Here are just three examples of student loan borrowing gone bad:

• I interviewed one young woman who has racked up more than a quarter of a million dollars in student loans for an undergraduate degree that she isn’t using. She’s waiting tables. She borrowed every dime of the cost to attend a private college in New York, saying she didn’t realize that she was strapping herself to an unbearable burden of debt. Most of what she owes is private student loans, which have variable rates and few of the consumer protections that come with the federal version. Her inability to pay her debt means that she can’t go on to get the graduate degree she needs to succeed in her field.

• A middle-aged woman contacted me because she and her husband were draining their savings trying to pay their debt. These middle-aged parents had borrowed more than $200,000 in federal PLUS loans to send their two daughters to college—only to have their $300,000 income cut by more than half during the recession. These parents likely will be making $1,000+ monthly payments on this debt for the rest of their lives because they can’t discharge the loans in bankruptcy and other payment options available to lower-income borrowers won’t help them reduce the load. Retirement is a fantasy—the husband can’t imagine a scenario where they could voluntarily give up working.

• A single mother of four daughters asked for help after she finally landed a job paying $30,000 following 18 months of unemployment. Even though she’s able to make payments on her student loans again, her balance continues to rise because she can’t even cover the accumulated interest. One of her girls has a serious medical condition, and between paying rent and health-care expenses, there’s little left over. The mother is 51 now and scared this debt will follow her forever.

Stories like these have shaken Americans’ longtime faith in the value of a college education. Before the recession, three quarters of those polled for The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education believed a college education was more important than in the past and that there could never be too many college graduates. In 2011, by contrast, 6 out of 10 Americans told Pew Research Center pollsters that a college education isn’t a good value for the money.

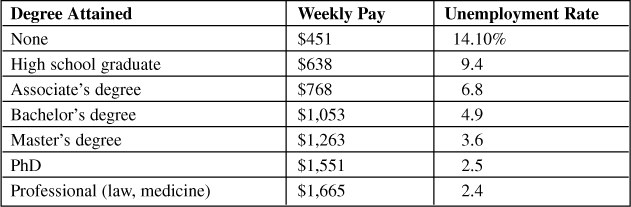

In fact, a college degree is actually worth more than it used to be. In the 1970s, those with four-year degrees earned an average of 25% more than high school graduates. Today, they earn about 60% more. That’s in part because low-skill jobs are disappearing rapidly thanks to advancing technology, changes in our economy, and increased outsourcing of jobs overseas. A college degree is no longer seen as a ladder up; it’s a life raft in a stormy economic sea (see Table 6.1).

Table 6.1. Median Salaries and Unemployment Rates by Education

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011

College degrees are also a profitable investment for most people. The College Board estimates that college graduates earn on average 66% more than a high school graduate over a 40-year working career.

As college enrollments have climbed, however, so have college costs. According to the College Board, the inflation-adjusted cost of tuition and fees at public four-year colleges more than tripled in the past 30 years—it rose 257%. The tab at private nonprofit four-year colleges rose 167%. The average total price tag—including tuition, room, board, books, transportation, and other expenses—for a four-year public college was just under $23,000 for 2012–2013, whereas the average total for private four-year colleges was about $43,000. The price tag for elite schools was closer to $60,000.

The nature of financial aid has changed as well. Whereas most aid in the 1980s was in the form of grants, by the mid-1990s the greatest portion of student aid came in the form of loans.

These changes have led to a rather stunning rise in the level of student indebtedness. The average college student graduated with about $26,500 in loans in 2011, according to a report by the Institute for College Access and Success’s Project on Student Debt. The percentage of households with student loan debt more than doubled between 1989 and 2010, Federal Reserve figures show.

Most people take on this debt at a time when they have no income, little credit savvy, and no clear idea how much this money will cost to pay back. Few realize what a crushing burden student loans can be—and unlike most other unsecured debts, student loans can’t be wiped out in bankruptcy court, meaning that people are saddled with it for life.

I wrote about Michelle from Indiana in my previous book, Your Credit Score. She graduated with $120,000 in student loan debt, but her job at a university pays just under $50,000. She was contemplating bankruptcy, not realizing that a 1998 change in the law made it virtually impossible to erase federal student loan debt. (Private student lenders won similar treatment for their loans as part of the bankruptcy reform law that went into effect in 2005.)

Kim also is staring at a debt she doesn’t think she can repay. She went to college late, after she’d had four children. Now she teaches at a public school near Sioux City, Iowa, where a beginning teacher makes about $27,000. But her student loan debt is a whopping $87,000, and the small payments she can make don’t even cover the interest owed.

“How will I ever be able to pay back this loan, plus the loans that I am now taking out for my two oldest children?” Kim wonders. “I have two more children who will be entering college in the next four years. I would love to be able to pay back these loans, but once again, how?”

Charles is in a similar fix, with student loan debt that’s growing because his income is too low to make the minimum payments.

“I was prematurely forced to leave school near the end of my doctoral program because of a divorce. I have a huge student loan that I have no hope of paying unless I win the lottery,” Charles wrote. “I can’t make the full student loan payments and am on an income-sensitive repayment program... My loan just keeps getting bigger and bigger. I have inquired in just about every way I can think of for some way to get relief from my loan. It seems there is none.”

Other student debtors find they can make their payments but can’t afford to do much else. They postpone important goals, like buying a home or saving for retirement, so that they can pay down their student loan debt.

But putting off these goals is an expensive choice. A 22-year-old who put $4,000 into a Roth IRA, for example, could watch that money grow to more than $125,000 by the time she’s eligible for full Social Security benefits. If she put off that contribution by 10 years, it would grow to less than half that amount—about $59,000. (Both examples assume an 8% average annual return.)

Few students are told about these potential costs, though, and most find no difficulty in getting loans to pay for as much education as they want. In fact, many students tell me they had no clear idea how much they had borrowed until they got their first bill six months after graduation.

Undergraduate students do face maximums on how much they can borrow under federal student loan programs, but private lenders have no such limits. They usually give students, or their parents, the difference between their college costs and any financial aid they get.

Graduate students and parents can borrow up to the full cost of an education, minus any other financial aid, through the federal PLUS loan program. There are no income or employment checks; in other words, borrowers don’t have to prove their ability to repay the loan. There’s a credit check, but it’s a generous one—if you haven’t had a bankruptcy, foreclosure, or repossession in the previous five years, and you aren’t currently 90 or more days late on a bill, you should be approved.

Lenders can be so generous because they know how hard it is these days to default. Collection agencies have excellent systems for tracking down student borrowers and getting them to pay. The federal government can, and does, seize tax refunds, garnish wages, and withhold portions of Social Security benefits when student loans aren’t repaid.

So What’s the Good News?

The good news is that federal student loan debt is flexible, relatively cheap, and available to folks who may not have much, if any, credit history.

The unsubsidized rate on a Stafford federal loan at 6.8% might not feel cheap to you—particularly when mortgage rates dropped below 4% and people with good credit can get car loans for 1% or even less. But, historically, student loans have been among the least expensive unsecured debt you can find. Subsidized student loans can have rates as low as 3.4%.

What’s more, federal student loans offer a variety of ways to structure and pay off your debt. If you lose your job or otherwise can’t pay, you can get a forbearance or deferral for up to three years. If your budget’s tight, you can opt for income-sensitive or graduated repayment programs.

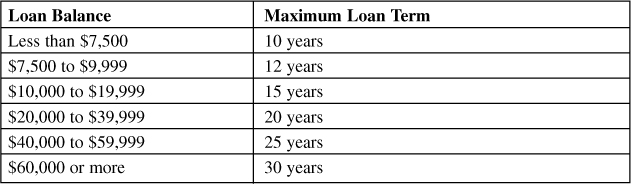

Most borrowers can take longer than the standard 10 years to pay back their loans if they want (see Table 6.2). Stretching out the term means you may pay more in interest—typically, a lot more. Going from a 10-year to a 20-year repayment plan more than doubles the interest you pay over the life of the loan. But lower minimums can help you manage your student loan debt and still have money left over to save for retirement or buy a home.

Table 6.2. Maximum Loan Terms Available for Federal Student Loan Debt

Source: FinAid.org

How Much Should I Borrow?

Because lenders see no reason to limit how much you borrow, it’s up to you to apply the brakes.

If you’re a student, your student loan payments once you graduate shouldn’t exceed 10% of your expected monthly gross income. That means you’ll probably need to limit your total borrowing to no more than you expect to earn your first year out of college.

You can check average starting salaries in your field by visiting the National Association of Colleges and Employers Web site at www.naceweb.org.

This rule of thumb is meant to be a guideline. You may opt to borrow more if, for example, you can reasonably expect your income to climb pretty steeply after graduation. (Lots of law school graduates, for example, start out in low-paying jobs before moving on to get the big bucks.)

You may want to be even more conservative if either of the following is true:

• There’s any chance you won’t get your degree. Your education won’t be worth much in the job market unless you actually graduate.

• You’re going back to school in midlife. It’s harsh, but people over 40 often face a tough job market, and they have fewer working years over which to “amortize” the cost of any education loans.

Lori in Westfield, Indiana, learned those realities a little too late. She went back to school in her thirties after earlier earning an associate’s degree, but she dropped out before graduation. Her combined student loan debt has swelled to more than $100,000—but so far the best job she’s found pays less than $33,000 a year.

“I’ve since learned an incomplete degree is the same as no degree,” Lori said. Her problems paying her debt have led to a basement-level credit score, and she despairs of ever having enough money to buy her own home or save for retirement.

You also should strongly consider limiting your borrowing to federal student loans because their fixed rates and consumer protections make them a much better deal than private loans. Unfortunately, the limits on federal loans aren’t particularly generous—just $5,500 your first year, and typically no more than $31,000 for your undergraduate education. Given that the price tag for an in-state, public university averages about $23,000, and elite schools are charging $60,000 and up, you may need to look for alternative strategies to get an education you can afford.

You could fill the gap between the college’s cost and available federal loans by using private student loans, but beware. Private loans have variable rates that often aren’t disclosed until after you apply. You’ll likely need a cosigner, which means someone else will be equally responsible for the debt (and that you can trash their credit if you can’t pay). As noted previously, if you’re a parent or a student planning to attend graduate school, the limits on federal loans essentially disappear. That makes it even more important that you set your own limits because Uncle Sam will allow you to borrow far, far more than you can comfortably repay.

If you’re a parent, you should ensure that loan payments don’t eat up more than 10% of your income and that you can pay off the loan before retirement while still saving adequately for retirement. If you can’t do that, you can’t afford the loan.

If you discover that the amount you should borrow is well below the amount you think you need to pay for school, it’s time to consider some alternatives:

• Go to a college that wants you. A school that’s actively trying to recruit you often will offer a much better financial aid package than one where you’re fighting to get in. One key is to look for schools where your SAT scores are in the top 25% of the student body. Lesser-known schools away from the big cities on the coasts are often more willing to boost aid packages to woo candidates. Also, many schools recruit for specific skills or talents, or even to improve their geographic diversity. Talking to recruiters at college fairs can help you get an idea of what they’re looking for. You’ll find many more suggestions in Lynn O’Shaughnessy’s book, The College Solution.

• Consider cheaper schools. Lots of students attend a two-year school first and then transfer to a four-year institution. It’s the four-year school’s name that will be on your diploma, after all. Another option is public schools instead of private, although some private schools are more motivated to discount their price than public schools can be, given state budget cuts.

• Go to work. A part-time job during the school year, a full-time job in the summer, or alternating a semester of work with a semester of study can help reduce the amount of money you need to borrow.

Where Should I Get My Loans?

Even if you don’t expect to get any need-based financial aid, you should still fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) so you can access the federal student loan program. If you do have financial need by the government’s definition, you’ll qualify for the lowest rates, and the interest on your subsidized loans will be paid by the government while you’re in school. Subsidized loans include the following:

• Perkins loans. These come with a 5% fixed interest rate, and you can borrow up to a maximum of $27,500 for undergraduate education and $60,000 for undergraduate and graduate school combined. Perkins loans can be canceled if you work in certain fields, such as nursing, law enforcement, Peace Corps volunteering, or teaching in a low-income area.

• Subsidized Stafford loans. Stafford loans have a fixed interest rate of 6.8%, plus a 4% origination fee that’s usually deducted from your payout. Students who demonstrate financial need can get a rate of 3.4% as of this writing.

In the past, many federal student loans were made by private lenders that enjoyed big subsidies from the federal government. That program was deemed financially inefficient and eliminated by President Obama at a savings of more than $60 billion over 10 years. Now all federal student loans are made directly by the government.

If you’ve exhausted your federal loan options and are willing to take the risk of private student loans, consider starting your search at www.custudentloans.org, which represents member-owned credit unions. The rates offered by these lenders are often lower than those charged by for-profit lenders.

If you’re a parent with excellent credit who can pay the loan off quickly, private loans may be a better bet than PLUS loans, O’Shaughnessy advised. Or you might consider tapping your home equity, if you have any, via a fixed-rate home equity loan or a variable-rate line of credit. You’ll be using an asset you may need later for retirement, and you’re putting your home at risk, so consider this option carefully before you act.

What If It’s Already Too Late?

If you’ve already graduated with a pile of debt, don’t despair. You may have more options than you think, at least with federal loans:

Explore loan forgiveness. A variety of state, federal, and private programs either erase student indebtedness or offer subsidies to help pay it off. Typically, you need to volunteer, perform military service, or teach or practice medicine in underserved areas.

Another option came on line in 2007: federal loan forgiveness programs that erase your remaining balance after as few as 10 years of payments.

The program is ideal for those who have big federal student loan debts and small incomes. If you sign up for the “income-based repayment” option, your monthly payments will be limited to 15% of your “discretionary income,” defined as the amount of your income over 150% of the poverty line for your family. If your income is low enough, your required monthly payment may well be zero. In any case, payments under the program typically are less than 10% of your gross income, said Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of the FinAid and Fastweb financial aid sites.

If you don’t have a public service job, your required repayment period would be 25 years. Public service jobs include, among others, those in public safety and law enforcement, military service, public health, public education, public interest legal services, social work in public or family service agencies and jobs at tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organizations. Government employees also are considered to have public service positions, although interestingly enough, time served as a member of Congress doesn’t count.

Parent PLUS loans aren’t eligible for the income-based repayment program, although they may qualify for the less-generous income-contingent plan if their loans were consolidated into a Direct Consolidation Loan after July 1, 2006. If that’s the case, those loans also may qualify for a forgiveness program.

FinAid.org has a section on loan forgiveness that lists many of the available options.

Consolidate your debts. Consolidation allows you to refinance your student loans into one large loan with one monthly payment. You typically can choose a longer payback period than the standard 10-year term, and you probably should. Opting for a 20- or even 30-year schedule will keep your minimum monthly payment low, but you can always make bigger payments to get the debt paid off faster. This approach will give you flexibility in good times as well as bad.

Consolidation is usually a one-time deal: Once you’ve consolidated a loan, you can’t do it again, even if interest rates drop. However, consolidation also resets the clock on how long you have to pay the loan. Plus, you can qualify for deferments or forbearance again even if you’ve exhausted your options on your current loans because the consolidation is considered a new loan.

Consider alternatives if money is really tight. You can defer payments on your federal student loans for a total of three years in most cases through deferral or forbearance programs.

These are not the best options if you can pay the minimum you owe because interest typically continues to accrue and swell the size of your loans. But if you’re unemployed, underemployed, or otherwise facing a serious income shortage, these options can offer temporary respite.

What you don’t want to do is ignore your debt. Late or inadequate payments typically are reported to the credit bureaus, which will damage your credit score and ability to get future loans.

Defaulting—failing to make the agreed-upon payments for nine months or more—is even more serious. The government has powers to collect on student loans that other debt collectors envy. It can

• Garnish your wages without a court order and seize your IRS refunds.

• Take a portion of your Social Security checks, which are usually off-limits to creditors.

• Follow you to your grave because there’s no statute of limitations on collections for student loans, as there are for other debts.

Several states also allow their professional and vocational boards to suspend, revoke, or deny licenses to people who have defaulted on their student loans. If you need such a license to work, you could be in bad shape.

If you’ve already defaulted, try to get back on track as soon as possible. Federal student loans can be “rehabilitated.” This means that in exchange for making several months of on-time payments, any mention of your default is erased from credit bureau records. (Contact the U.S. Department of Education at 800-621-3115.)

Consider settling your federal student loan debt. If you have defaulted on your student loans but can round up a significant lump sum to pay them off, it may be possible in some situations to settle the debt for less than what the government says you owe, Kantrowitz said.

Don’t expect to settle for pennies on the dollar, as might be possible with old credit card debt. But you may be able to get the government to waive some of the fees and accumulated interest.

If you’re having trouble paying your private student loans, your options are far fewer. Some lenders offer forbearance or deferral; others don’t. One of the biggest complaints about private student lenders is their unwillingness to offer affordable repayment plans to borrowers who have hit tough economic times.

For more on dealing with lenders and student loans in general, visit the Student Loan Assistance Center at the following Web site: http://www.studentloanborrowerassistance.org/.

What About Paying Off My Student Loans with Home Equity Debt—or Credit Cards?

There are situations when trading student loan debt for other kinds of debt can be advantageous if you lock in a lower interest rate, but this kind of refinancing is fraught with peril.

Few debts are as flexible as federal student loans. Remember, if you lose your job, you can get a deferral or forbearance so that you don’t have to make payments for up to three years. Try that with a home equity debt or credit cards, and you’ll wind up in foreclosure or collections.

Up to $2,500 of interest on student loan debt is tax deductible, and you don’t need to itemize to get the break. (There are income limits; the deduction began to phase out at a modified adjusted gross income of $125,000 for married taxpayers and $60,000 for singles in 2012.) As I mentioned in the preceding chapter, you have to itemize to be able to deduct interest on home equity debt. And credit card interest isn’t deductible at all.

Credit card rates are typically variable, and can soar to punitive levels if you’re 60 days or more late with a payment.

If you opt for a home equity line of credit, rather than a loan, your rate can climb as well, not because of any fault of your own but thanks to changes in short-term interest rates. Caps on HELOCs typically are around 18%, which is much higher than the cap on your federal student loans.

If you’re having trouble paying your student loans, you may be wondering whether you could transfer your debt to credit cards so you can get the burden erased in bankruptcy court. Technically, this is possible, if you have sufficient open credit on your cards. But you also would be committing fraud. Such transfers tend to attract the attention of bankruptcy court officials, who could toss out your filing and leave you potentially worse off than you are now.

Given all this, most people are better off sticking with their student loans and simply paying them down faster if they want to reduce total interest costs.

Summary

Student loans can be an investment in your future, but it’s easy to overdose on this so-called “good” debt.

Credit Limits

• If you’re a student, you should limit your total borrowing to what you expect to make your first year out of school and consider limiting yourself to federal student loans only.

• If you’re a parent considering borrowing money for your child’s education, make sure you’re saving adequately for your retirement before you commit to student loans. Your student can always get his or her own loans, but no one will lend you money for your retirement.

• Keep tabs on how much you’re borrowing, the type of loan, and who you’re borrowing from. It’s easy to lose track of your total debt when you’re borrowing from different lenders over time, as many students do.

Shopping Tips

• Federal student loans offer the best rates and terms, so take full advantage before you opt for private loans.

• For maximum flexibility, consolidate your loans and opt for the longest available payback period. You can always make larger payments to reduce your total interest costs, but most people find they have more important financial priorities than accelerating payments on their student loan debt.

• Consider the income-based repayment option if you have big federal student loan debts and a small income. Your balance could be forgiven after 10 years if you work in public service and 25 years otherwise.