3. Credit Cards

Some people view credit cards the way prohibitionist Carry Nation viewed alcohol: a hideous evil visited upon an unsuspecting and easily duped public.

It’s true that credit cards have paved many a road to financial ruin. The bankruptcy rate attests to that, as does the fact that millions carry credit card balances at rates so high that they would have been illegal 50 years ago. There’s no question that some people would be better off without plastic. Many others would have a lot more cash in their pockets if credit card companies weren’t so fiendishly creative at finding ways to snatch it away.

But just as most people can have a cocktail without ruining their lives, most people can handle a credit card or three. The oft-repeated statistic that Americans carry an average of $9,000 in credit card debt is actually bunk (more on that later). A large group of credit card borrowers (about 40% by most estimates) use cards solely for convenience, charging balances that they pay off in full each month.

Credit cards provide protections that simply aren’t available if you pay by cash or check. The credit card company serves as a middleman if you have a dispute with a merchant, and it can even help you replace purchases that are lost, broken, or stolen. (If you have a gold or platinum card, check the benefits guide that came with it. Chances are you’ll be pleasantly surprised at the perks you’ll find.)

If someone steals your card or uses your account number without permission, you’re typically not liable for a dime. (Most issuers waive the $50 fee they could legally charge.) Then there are all the rewards you can rack up with the right card—cash back, free flights, upgrades, hotel stays, and merchandise.

Credit cards can provide an important safety valve as well. All but the fattest emergency funds can be drained by a long stint of unemployment. Living on credit cards isn’t the best way to survive a financial crisis, of course, but it can work.

When people get in trouble is when they let credit cards tempt them into living beyond their means.

It’s pretty easy, after all, to just pay the minimum when the credit card bill comes due. In the old days, paying just the minimum meant you could be footing the bill for literally decades. Card issuers weren’t required to set minimums high enough so that you’d pay down your balance. Now they are, but you can still wind up paying for purchases for years. Every dinner you’ve long since digested, every toy that broke years ago, every household gadget or piece of clothing that’s been donated to the Salvation Army—all paid for two times over, or more.

Now, imagine that instead of sending that money to a credit card company, you invested it instead. Over your working lifetime, an extra $100 a month could result in a nest egg of nearly $350,000, assuming your investments earned an average 8% annual return.

That’s a pretty steep price to pay for the “convenience” of not paying off your balance.

Carrying a balance also leaves you vulnerable to the many different ways credit card companies have devised to ding their customers, from rates that soar overnight to sneaky balance-transfer fees. (Again, you’ll consider lots more on that in a minute.) If you don’t carry a balance, you don’t have to care what rate your issuer charges—because you’re not paying interest anyway.

Aren’t there exceptions? You might have been led to think that any type of debt is okay, as long as you don’t overdo it and you manage it correctly. But that’s not true when it comes to credit cards.

Credit card debt is simply corrosive. Much of the time, it’s ridiculously expensive, and even when it’s not (listen up if you’ve received low-rate balance-transfer offers), it encourages people to spend more than they make, which is never a good financial habit to acquire.

People who play the balance-transfer shuffle—moving their debt from one card to another in search of low rates—could be doing themselves a particular disservice. All those accounts can ding your credit score, as can moving money from one card to another with a lower credit limit. Do it long enough, and you may find that your score has suffered enough that the low-rate offers suddenly dry up, stranding you with a big debt on a card that’s about to jack up its rate.

Carrying credit card debt is not the norm in America, despite what we’re frequently told.

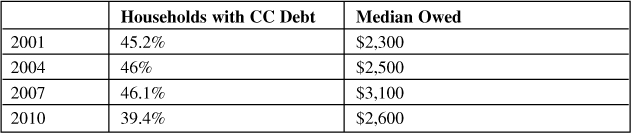

Most Americans owe nothing to credit card companies, according to detailed figures compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank in its Survey of Consumer Finances. In 2007, 46.1% of U.S. households had any credit card debt. By 2010, that proportion dropped to 39.6% (see Table 3.1).

Source: Federal Reserve. All amounts in 2010 dollars.

Of the households that did carry a balance, the median amount owed was $2,600. That means half of the households with a balance owed more, and half owed less.

So where did we get the idea that the average American is $9,000 (or $10,000 or $12,000 or $15,000) in hock? Most often, the statistic comes from dividing outstanding credit card debt by the number of households that have a credit card. Of course, some of this debt will be paid off the following month. Even if that weren’t true, any average created with this method would be misleading.

Need an example? Imagine yourself in a room with nine friends—and two of those friends are Bill Gates and Warren Buffet. The average net worth of a person in that room would be about $10 billion, even if the rest of you are flat broke. Gates and Buffet are so mind-bendingly rich that they skew the average.

A similar, if less dramatic, phenomenon seems to be happening with credit card debt. Most folks don’t have any, and most of those who do don’t have much. But a few folks have a lot, and that skews the average.

The continued repetition of these bogus statistics does a real disservice to people with credit card debt because it can mislead them into thinking that they’re the norm—that carrying debt on plastic is how you’re “supposed” to live your life. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In fact, if you want to achieve financial independence one day—that is, if you ever want to retire or have enough money to chart your own course—you need to learn this lesson. While you’re at it, teach it to your kids:

Pay off your credit card balances in full every month.

The only exception, as I’ve noted, is when you’re experiencing a true financial emergency like a job loss. In that case, you’ll want to preserve your cash.

Running out of cash before you run out of month isn’t an emergency. That’s just overspending. If you encounter that situation, go into savings over-drive to come up with the cash to pay your cards. Sell something. Eat beans and rice. Bike to work to save gas. Do whatever it takes to get in the habit of relentlessly, religiously paying off your credit card bill.

Of all the financial lessons my mother taught me, this was one of the most important. My mother was so dead set against paying credit card fees of any kind that when her Visa card first introduced an annual fee, she cut up the card and sent the shards back to the bank. (Within a few weeks, she received a new card with the fee waived—and a letter of apology.)

Not owing credit card debt has freed me in so many ways. When I was first starting out, I had more money than many of my peers to save for retirement and spend on the things I enjoyed, including travel. When the newspaper I was working for in 1992 abruptly shut down, I learned that I had enough cash saved—and my expenses were so reasonable—that I could easily survive for a year without touching my retirement savings. While others panicked, I had the luxury of figuring out what I wanted to do next and even turned down a few jobs before I found the one I wanted. Now that’s freedom.

Our Love Affair with Credit

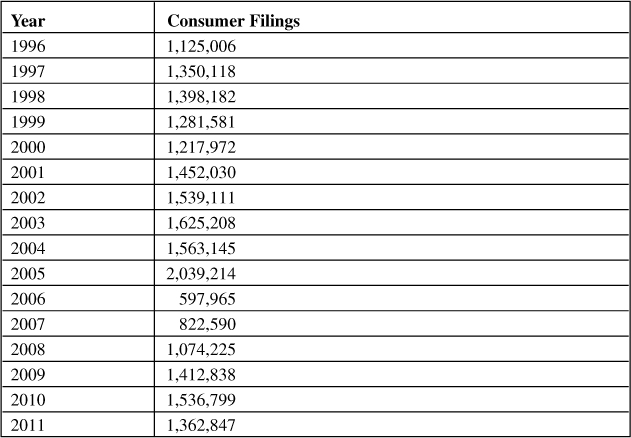

Unfortunately, it’s a freedom many people don’t know. Consumer bankruptcy filings first topped one million in 1996, and continued to grow more or less steadily after that (see Table 3.2). Congress took note, and decided the solution was to make bankruptcy harder to file starting in late 2005. Bankruptcy filings topped two million that year as consumers rushed to file under the old rules. Bankruptcy cases dropped the next year—but then started to march higher. Indeed, if you add the filings for 2005 through 2007 and divide by three, you’ll find the average is about 1.1 million—about the same number that got Congress so upset in the first place.

Table 3.2. Bankruptcy in America

Source: American Bankruptcy Institute

Many condemn bankruptcy as a symptom of a “live for today” ethic or on baby boomers who never learned the meaning of delayed gratification.

The truth is much more complicated.

Household incomes have been stagnant for years. The median income in 2012 was, when adjusted for inflation, about the same as in 1996. Meanwhile, costs for health care and education have outpaced the rate of inflation for years. Employers are shifting more health insurance costs to workers, squeezing their paychecks even further. Those workers are the lucky ones because so many people have no health insurance at all.

So we shouldn’t be surprised that many consumer bankruptcies are precipitated by medical bills. One study at Harvard University suggests that medical debts are a factor in as many as two thirds of consumer bankruptcies.

Lack of savings and significant credit card debt are other factors that can tip a family over the edge into bankruptcy, particularly when they face a financial setback, like a job loss or divorce.

People also can get into trouble when they use their personal credit to launch or maintain a small business. One out of three new businesses fail within five years, according to the Small Business Administration, and many take their owners’ credit with them.

The explosion of available credit has had a profound effect on who has debt and how much they carry. For years, credit card issuers and other lenders were pretty cautious about how much credit they would extend, and to whom. It wasn’t until the U.S. Supreme Court essentially nullified state caps on interest rates in 1978 and Fair Isaac introduced its first credit bureau-based score in the mid-1980s, that card issuers got more confident that they could properly manage the risks involved in extending more credit to a wider group of people. Now that they could charge essentially any rate they wanted, the credit card companies figured they could take on riskier clients—and make them pay proportionately for the greater chance of default they presented.

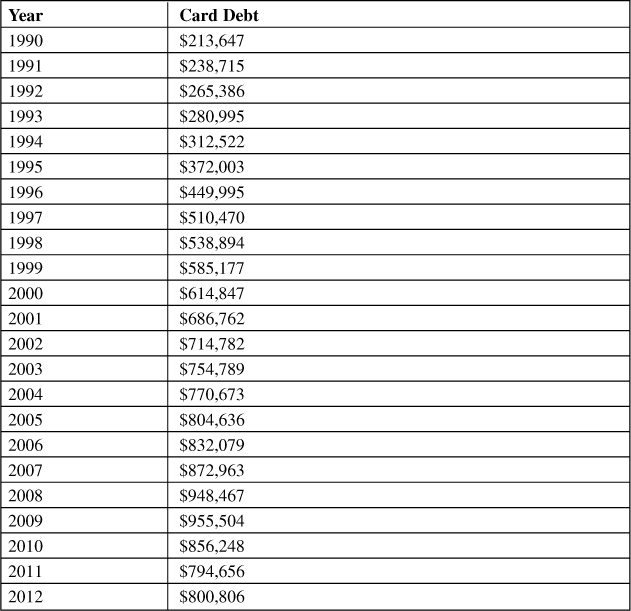

Table 3.3 shows how credit card charging soared in the 1990s and beyond.

Credit card charges as of January each year, in millions

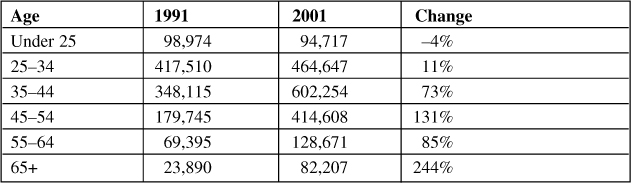

The explosion in credit between 1990 and 2008 affected everyone—not just the baby boomers. Credit card issuers plied college campuses, and most students (more than 80%) took them up on their offers. Older people weren’t immune, either. People over 65 were the fastest-growing group of bankruptcies in the 1990s, as shown in Table 3.4. The Consumer Bankruptcy Project hasn’t updated those numbers, but the Institute for Financial Literacy found that bankruptcy filings for people 45 and older increased 19% between 2005 and 2010.

Table 3.4. Changes in Bankruptcy Filings by Age of Filer

Source: Consumer Bankruptcy Project

So it’s not just the young and naïve or baby boomer spendthrifts. Credit problems can afflict people at any age.

The True Cost of Carrying a Balance

Carrying a credit card balance makes you more vulnerable to whatever setbacks life throws your way. Every dollar you’ve charged is a dollar you can’t access in an emergency, and your card issuers want at least their minimum payments, regardless of whether you have a job. Credit card debt might not be the primary reason most people file for bankruptcy, but it’s certainly a contributing factor in many cases.

If you need more convincing that carrying a credit card balance is a bad idea, let’s review a few of the ways credit card companies have devised to part you with your hard-earned cash when you don’t pay your balance in full.

Floors But No Ceilings

Most credit cards these days have variable rates that are tied to some short-term rate benchmark, like the prime rate. Theoretically, when the Federal Reserve reduces short-term rates, what you pay on your credit card should drop as well.

But many credit card lenders have created interest-rate “floors” to protect their profits. The rate can’t drop below this minimum, no matter what’s happening with interest rates in general. That’s why in 2012, when interest rates were effectively near zero, most credit cards charged 16% or more.

While card issuers have limited their “downside,” there’s really no limit on their “upside”—how much they can charge.

Overnight Rate Changes

Some people think they’ve protected themselves from the slings and arrows of outrageous rates by opting for a fixed-rate card. In reality, there’s no such thing in the credit card world as a “fixed” rate. No matter how ironclad you think your rate guarantee is, the credit card company can wriggle out of it thanks to the fine print in the application you signed—or in those little brochures the credit card company sent you after you got your card.

Sometimes they really bury the notice.

Jim in Portland, Oregon, received a fat envelope from one of his credit card issuers recently.

“When I opened it, there were multiple inserts, many with large print and colorful graphics, offering anything from Matchbox toy cars to multiple free gifts, where the customer pays only the shipping charges. The smallest insert, with by far the smallest type, was a brochure notifying me of an increase in my [interest rate]. It went on to say that the increase was not due to my account history or behavior. They just decided to make a business decision to increase it to these new terms. When I called the company, they were very vague and couldn’t really explain the increase other than ‘We have the right to do so.’’’

Before the Credit CARD Act of 2009, the card company had to give you just 15 days’ notice to change any of the rates, terms, or conditions on your account. If it had already warned you that certain behaviors can spike your rate, the change could happen overnight. Now, issuers are required to give you at least 45 days notice, and the credit card reform law also outlawed some of the card companies’ most egregious tactics, such as jacking up your rate for any or no reason. Today, your rate on an existing balance can’t be increased unless you’re 60 days or more late with a payment. Issuers also aren’t allowed to hike your rate on an existing balance if you’re late with a payment on a different account (something called a “universal default” clause that was common before reform). Also banned is double-cycle billing, which had you paying interest on a balance even after you’d paid it off.

Issuers are still allowed, with proper notice, to change your rate going forward. Your current balance may have a low rate, but any new purchases could incur a much higher one. Rates aren’t the only thing the card issuer can alter abruptly. Many people who run into serious financial trouble find that their card companies begin to lower their credit limits—the amount the customer is allowed to charge each month. During the recession and even afterward, many readers reported their issuers were “chasing down the balance”—lowering their credit as people paid down their debt.

Fees and More Fees

Over-limit and late fees became a huge profit center for credit card issuers. In the years before the CARD Act, fees made up about a third of bank revenue, according to R.K. Hammer Investment Bankers. And those fees were stiff.

In the early 1990s, the typical late payment was about $10. By the mid-2000s, the average was close to $30, and several card issuers have instituted “tiered” late fees that can push the toll even higher. Those who owe less than $100 might pay $15, while those who owe $1,000 or more might pay $39. The bigger late fees turned into a trap for maxed-out consumers. The late fee could put them over their credit limit, which triggered—you guessed it—an additional, over-limit fee.

The CARD Act didn’t eliminate late fees, but it did require issuers to get consumer consent for over-limit fees. In essence, consumers had to “opt in” to over-limit transactions; if they didn’t, the issuer was required to reject any transactions that exceed their credit limits. Because few consumers ever wanted over-limit protection in the first place, it’s no surprise that few signed up for it. Over-limit fees all but disappeared.

Balance-Transfer Roulette

People with good credit often get flooded with offers encouraging them to move their debt to a new card at a temptingly low rate. These offers are typically loaded with booby traps:

• Rates that go “sproing!” Most of the rates offered on balance transfers are fairly short-term—three to six months, typically. Then the rate can leap higher than the one you’re already paying. You may fully intend to transfer the balance again before that point, but card issuers know that many will forget to switch in time and others may not be able to find a better rate. Even the offers that promise a “low rate for the life of the balance” have tricks up their sleeves, as you’ll see next.

• Balance-transfer fees. Many lenders tack on a fee equal to 2% to 5% of your balance when you take advantage of their offers. Depending on how long it takes you to pay off the balance, that fee could wipe out any interest rate advantage of the lower-rate card.

• Higher rates for purchases. Most cards that offer low balance-transfer rates have much, much higher rates for new purchases. And, importantly, any payments you make are deducted from the low-rate portion of your balance first. Your higher-rate debt continues to accumulate interest. Some cards pretend to get around this by offering a low rate for purchases as well, but typically that rate leaps upward after a few months. If you haven’t paid off the balance-transfer portion, you start paying big bucks in interest on those purchases.

• Expensive add-ons. The offers sound tempting: Pay a small fee, and you won’t have to make payments if you lose your job, become disabled, or die. Although these offers sound like insurance, which would be regulated by the state, they’re actually known as debt-suspension or debt-cancellation contracts and were largely unregulated before the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau decided to step in. The CFPB said lenders were engaging in deceptive marketing; after a couple big issuers had to pay fines, others decided to phase out this once-lucrative business.

• The incredible shrinking credit scores. As I mentioned earlier, playing the balance-transfer game can damage your credit scores, the three-digit numbers used in most lending decisions. Merely applying for a new card can ding your scores; so can transferring a balance from a high-limit card to a lower-limit one. Many people make matters worse by closing out their old cards once their balances are transferred to the new ones. (Remember, closing accounts can’t help your credit scores, and may hurt them.)

Despite all the ways they can trip you up, balance-transfer offers also can help you climb out of credit card debt if you use them correctly. The key is to focus on using the low rate to help you pay off the balance, instead of as an excuse to continue carrying debt.

Your goal should be to pay off your balance, or as much of it as possible, before the low rate expires. With a $2,000 balance at 0% interest, for example, you’d need to make monthly payments of at least $334 to pay off the balance in the six months these offers typically last. At 4.99%, boost your payments to $338.

Web sites like Bankrate.com, CreditCards.com, NerdWallet, and CardRatings.com also can help you hunt for good offers.

In addition, take the following precautions:

• Consider alternatives. If you can’t pay off your balance before the introductory rate expires, consider shopping instead for a card with a low, fixed rate. No, you can’t guarantee the “fixed” rate won’t change, but you know the other card’s rate will climb—and you don’t know whether you’ll be able to score another great balance-transfer offer when it does.

• Know a good rate when you see one. If your credit is excellent—your FICO scores are 750 or more—you should be able to qualify for 0% balance transfer rates as well as longer term rates of 11% to 13%. If they are mediocre—in the 650 range—you’ll be lucky to pull in a rate below 20%, although the introductory rate may be lower. Not sure what your scores are? You can get a general idea by using the FICO score simulator on Bankrate.com.

• Scour the fine print. Find out exactly how long the low rate applies and mark the date on your calendar as soon as your card arrives. Avoid the offers that apply for just a few months or lenders that reserve the right to send you a higher-rate card if you don’t qualify for the low-rate offer.

• Know the fees. If the card charges a fee to transfer your balance, make sure you’ll save enough during the low-rate period to offset the additional charge. Again, the calculators at Bankrate.com can help with the math.

• Have another card for purchases. Even if the card boasts low rates for purchases as well as transfers, remember that any balances you owe when the introductory rates expire will start accruing interest at a much higher rate. It’s better to have a separate card for new purchases (and to pay those off in full every month).

Gotchas for Those Who Pay Their Balances

Once you get your balances paid off, you can breathe a sigh of relief that you’re no longer held hostage to the credit companies’ rate games.

That doesn’t mean you can lower your guard entirely. Because about 40% of credit card customers pay off their balances in full each month, card companies look for ways besides interest charges to ding them as well.

Late fees are the obvious ways credit card companies can still get you, but there are others as well:

• Cash-advance fees. There are few more expensive ways of getting cash than using your credit card—loan sharks come to mind. Typically, even the lowest-rate cards charge 19% or more when you get cash, and the charges start from the minute you pull out the money. There is no grace period, even if you don’t otherwise carry a balance. (The grace period is the time before interest charges accrue.)

• Less grace. Speaking of grace periods, those have been shrinking as well. It used to be that if you didn’t carry a balance, you had about 30 days from the day your statement closed before you had to pay interest. If you paid within that grace period, no interest charges would be due. Now the average grace period has slipped to 23 days, and sometimes even less; a few cards have no grace period at all, even if you don’t carry a balance. (If you do carry a balance, there’s no such thing as a grace period; your new charges begin accruing interest immediately.)

• Conversion fees. Taking your credit cards overseas used to be a great deal. You’d get the same great exchange rates that big banks get, instead of the lousy rates usually offered to tourists at storefront exchange outfits.

You can still get those boffo rates, but the advantage has been dulled because card companies charge a 1% to 2% fee on top of the 1% fee typically charged by Visa and MasterCard.

NerdWallet has on its site a list of cards that don’t charge any foreign transaction fees; you should get one if you travel abroad. Take a backup card as well in case your primary card is lost or compromised. Also it’s smart to call your issuers before you leave and let them know what countries you’ll be visiting; otherwise, their fraud-sniffing software could see the overseas transactions as a sign of theft and shut down your ability to use your card.

The Right Way to Pay Off Credit Card Debt

Hopefully I’ve convinced you it’s time to get rid of those credit card balances. You’ll want to review the information in the preceding chapter to make sure you’re coordinating your debt repayment plan with other important goals, like your retirement and increasing your financial flexibility.

Your next step should be figuring out if you can minimize your interest rates.

If you have excellent credit, this might be as simple as calling the credit card issuers to ask for a better rate. You might let them know you’ve been receiving some mighty tempting balance-transfer offers lately, which is often all the incentive they need to cut you a deal.

If they balk, you actually might use one of those offers to lower your rates. (If you haven’t gotten any lately, check for one on Bankrate.com or similar sites.)

If you come up empty or you don’t have good credit, consider transferring balances to your lowest-rate cards. Just make sure you’re not using up all your available credit; “maxing out” your cards can hurt your credit scores. The more of your credit line you use, the greater the potential damage, although you may want to take the temporary ding to speed up your debt repayment plan.

How about using a home equity loan or line of credit to pay off your balance? Yes, you can get a lower rate that’s tax-deductible to boot, but this isn’t a good choice unless your finances are otherwise sound and you can commit to not running up new balances. (For more details on the disadvantages of these loans, see Chapters 2, “Your Debt Management Plan,” and 5, “Home Equity Borrowing.”)

Using a loan from your 401(k) to pay off credit card debts is often a bad idea as well. If you lose your job, the unpaid balance can be penalized and taxed as an early withdrawal, and you lose all the tax-deferred returns you could have earned on the money.

Debt consolidation loans usually just stretch out your payments and jack up your overall interest costs and fees. Credit counseling—where a nonprofit negotiates a lower rate with your credit card companies—can have a negative impact on your credit. You should use it only if you’ve already fallen behind on your payments.

Most people can create and execute their own debt repayment plans without any outside help.

But you do have to stop using your cards.

There’s nothing like living on cash (or a debit card tied to your checking account, which is the next best thing) to help you learn to live within your means.

If your spending isn’t totally out of control, you can keep one card for “emergencies” and travel, but only if you commit to paying off the balance in full every month. If you can’t do that—and some people can’t—go cold turkey.

Now, the perennial question: Which balance should I pay off first?

You’ll find a variety of different opinions, depending on which debt guru you consult. Each approach has its benefits and drawbacks:

• Pay the smallest balance first. This approach gives you the psychological boost of achieving a zero balance quickly on at least one of your accounts, and that little victory could help you stick to your debt payoff plan. But if other debts are accruing at higher rates, you could wind up paying more in total interest.

• Pay the highest-rate balance first. This is probably the most-recommended plan of attack because you retire your costliest accounts first. But it may take you longer to achieve your first paid-off account, and it may not be the most helpful for your credit score.

• Pay the balance that’s closest to its limit. If one or more of your cards is maxed out, your credit scores could be suffering, and that could affect the rate you get on other loans. Paying down these high-balance debts can help your credit score and ultimately contain your total interest costs.

Sometimes it can make sense to use a mix of approaches. You might pay down the card that’s closest to its limit first, for example, and then start working on your highest-rate debt.

Whichever account you tackle first, your plan of attack will be basically the same. Pay as little as possible on your other debts, and throw every available dollar at the debt you’re targeting.

Once that debt is retired, you can decide on the next debt you want to eliminate and direct your money there, again paying the minimums on your other bills.

In the past, paying only the minimum could be risky because some card issuers penalized such borrowers by raising their interest rates. The assumption was that the borrowers were over their heads and about to default. As you know, card issuers now are barred from raising interest rates on existing balances, but you might want to consider paying a few bucks over the minimum to avoid having your rates raised for future purchases.

You can use debt reduction calculators available on many Web sites, including Bankrate.com, to see how fast your payment plan can retire your debt. Even seemingly small increments can help you toward your goal. Sending an extra $25 a month on a $5,000 balance could trim nearly 16 years off the time it takes to pay back the debt, according to debt expert Gerri Detweiler, and save you more than $3,000 in interest costs.

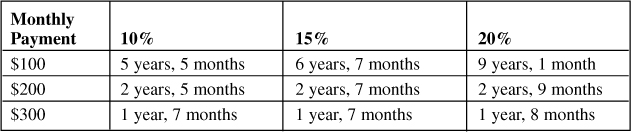

Table 3.5 demonstrates how fast larger payments can retire a $5,000 balance at different interest rates.

Table 3.5. Retiring a $5,000 Balance at Different Interest Rates

Another tip: Consider setting up some kind of automatic payment plan so that money is whisked from your checking account to your bills without your having to give it a whole lot of thought. Most people have busy lives and find that the fewer decisions they have to make, the better. You can set up an automatic debit plan that lets the credit card company take a set amount of cash from your checking account each week, or you can set up a recurring payment through your online bill payment system.

A final note: As you pay off your debt, don’t ask your credit card issuer to close your cards or lower your credit limits unless you really can’t control your spending. Closing accounts or lowering limits can hurt your credit score.

Getting the Right Reward Card

Everybody, it seems, is getting some kind of perk for using plastic: frequent-flier miles, cash back, rebates on cars, free merchandise, hotel upgrades, and theme park tickets. Your credit card can even help you save for college or retirement.

This proliferation of perks isn’t problem free, however. Card issuers have complicated their offers immeasurably in recent years by offering scores of ways to earn and redeem your rewards. Use your card at a certain grocery store, and earn more points. Redeem with a certain hotel, and get an extra day free. You get the picture.

That leads to a lot of second-guessing. Do I have the best card? Am I earning the most possible points? What’s the best way to spend them?

The answers to all these questions are fairly simple if you carry a balance from month to month. That’s because reward cards aren’t for you.

Reward cards have interest rates that are consistently higher—often much higher—than you would pay on a plain-Jane card. You might think that because you’re carrying a balance anyway, you might as well get the perks, but the finance charges you’ll pay will more than offset the value of any goodies you get.

You’re better off looking for the lowest-rate card you can find so that you can pay off your debt as quickly as possible. Once you’ve done that, you can start tackling the confusing world of rebate cards.

The best card depends on a lot of factors, including how much you charge, how much you travel, and how much flexibility you want in earning and spending your rewards.

To get the best deals, you’ll need to invest some time in choosing a card and managing it afterward. To get the maximum rewards, you’ll probably want to focus your spending on one or, at most, two cards; otherwise, you’ll have points scattered (and expiring) hither and yon, with too few on any one program to make much difference.

View your reward program as a kind of investment; the returns typically are commensurate with the amount of time and attention you give. You’ll want to pay attention to the statement stuffers or e-mail newsletters that come with your card because these typically give you tips on earning extra points.

Here’s what you need to know to get started:

Know your options. Most people have heard of cards that earn frequent-flier miles and those that offer cash back. Cards that give you future discounts on car purchases or leases are also popular.

But that’s barely scratching the surface of what’s available today. You can find cards that deposit rewards in your retirement or college savings accounts. Several issuers have cards that earn rebates on specific types of purchases, like gasoline, or on categories of spending, like entertainment. Disney and Universal have credit cards with rewards that can be redeemed for theme-park admissions, DVDs, and movie tickets.

If your goal is earning free travel, you’ll have to choose from a wide variety of options:

• Airline-affiliated cards. These cards earn you miles on a specific airline, like American or United. If you’re a frequent traveler who can concentrate most of your flights on a single airline, these are usually the best option to help you earn free tickets and upgrades.

• Travel-reward programs. If you have to spread your miles on different airlines, you might be better off with a card that gives you more flexibility. American Express and Diners Club both have well-regarded plans that allow you to redeem miles on a number of different airlines. Many Visa and MasterCard issuers also have reward programs with miles that can be redeemed on any airline.

• Hotel-affiliated cards. These cards offer points that can be used for flights or hotel stays—but the hotel stays are usually the much better deal. Typically, it takes about twice as much spending on a hotel card to earn a free flight than it would if you were using an airline-affiliated card. Hotel-affiliated cards might be a good idea for a traveler whose flights are usually paid for by an employer and who likes to add a day or two of sightseeing to the end of most trips.

You can research the various options at Web sites like NerdWallet, CardRatings.com and Bankrate.com. If you’re a frequent traveler, the Webflyer.com and FlyerTalk.com sites have terrific information about various airline- and hotel-related cards.

Match the card to your spending patterns. Both heavy and light spenders can run into trouble.

Cards that give you discounts on car purchases are among the most generous, but the rewards have their limits. The GM Card lets you earn 5% toward the purchase or lease of one of its vehicles, but the reward is capped at $1,000 if you want certain models, such as Chevrolet Equinox or Buick Verano. If you’re looking for a Corvette or an Escalade, though, you might be able to use a reward of up to $3,000.

The Subaru Rewards Card from Chase gives you a 3% rebate on purchases but limits the total you can earn each year to $500. That means if you charge more than $16,667 a year, you won’t earn any additional rebate.

If you want the discounts but you charge more than these levels, you can switch to another card (with a separate rebate program) after you’ve earned the maximum reward.

Light users face other problems. If you don’t charge much, you can quickly pay more in annual fees than you’ll get back in rewards.

For example, if you charge just $5,000 a year on a card that costs $60 annually, it will take you five years to earn a free airline ticket with most cards (assuming that one dollar spent earns one mile and that a ticket costs 25,000 miles). In that time, you’ll have paid $300 in fees—enough to buy a discount coast-to-coast ticket on your own.

People who don’t travel frequently with a specific airline often face frustration with trying to redeem their rewards. That’s because the airline’s elite frequent fliers usually get preferential treatment, leaving leisure travelers to face more restrictions and blackout days.

Even some of the no-fee, cash-back cards might not be the answer. Most don’t give a full 1% back until you reach certain spending levels. The Discover More card, for example, gives just .25% cash back on your first $3,000 of charges and 1% after that. That means you’ll earn just $7.50 on your first $3,000 in charges.

If you’re a light user, you may be better off with one of the cards that offers 1% from your first purchase, such as the no-annual-fee Capital One Cash Rewards, or one that offers higher rebates for certain purchases, like cards that give you rebates for gas.

Understand the exchange rate. Frequent-flier miles are the gold standard of rewards. They’re typically valued at 1 or 2 cents apiece. (However, they might be worth as much as 8 or 9 cents if you use them for upgrades on cheap coach tickets, says miles guru Randy Petersen, president and CEO of Frequent Flyer Services.) One or two cents is the same as a 1% to 2% rebate when you earn one mile per dollar spent.

Knowing the value helps in two ways. You’ll know better than to choose a program that offers rewards of less than 1%. You’ll also avoid squandering any miles you earn for merchandise or other conversions that give you much less value for your money—unless your reward is on the verge of expiring.

Know your limits. Speaking of expiring, you’ll definitely want to know how long you have to use your rewards before they disappear. Some airline-affiliated credit cards have a use-it-or-lose-it policy, for example, as do many “travel reward” plans not affiliated with a specific carrier. (These programs let you book a flight on any airline, without blackout dates, but they usually limit the ticket’s value to $500 or less.)

If you’re not a big spender or won’t be able to use your rewards for several years, make sure you have a card that allows you to bank your rewards. American Express and Diners Club, for example, are two cards with frequent-flier miles that don’t expire.

If you can’t use your miles to fly, you typically have plenty of other options. Most airline and travel reward cards give you alternatives, such as using your points to buy merchandise or hotel stays.

The conversion rate may not be great, though, which is why you want to use this only as a last resort. While 25,000 miles would buy you an airline ticket worth $500, for example, the same miles might pay for a hotel stay worth just $250 or merchandise valued at $100 or less.

You may also be able to convert your miles with one airline to another at a place like Points.com, but expect to lose 80% to 90% of their value in the conversion process—not a great option.

Protect your credit score. You may think you’re being smart by charging as many purchases as possible to rack up frequent-flier miles or other rewards. But you could be damaging your credit scores, which suffer when you use too much of your available credit limit.

It doesn’t matter if you pay off your bill in full each month. As I explain in detail in my previous book, Your Credit Score, the credit-scoring formula typically doesn’t differentiate between balances you pay off and those you carry from month to month. What usually matters is the balance that shows on the statement the credit card company sends you each month, which it reports to the credit bureaus.

That’s why it’s smart to limit your charges to no more than 30% of your available limit. If you go over 30%, consider sending in a significant payment a week or more before your card’s “statement closing date” (the last date that purchases and payments are recorded for the month). The closing date is usually listed on your statements; if not, call your issuer and ask. Reducing your balance owed in this way may help limit the ding on your credit score.

Summary

Credit cards can offer convenience, buyer protections, and even a source of emergency cash. But credit card debt is almost always toxic and should be among the first debts you pay off.

Credit Limits

• The best way to handle credit cards is to pay them off in full each month. If you can’t swing that right now, at least pay significantly more than the minimum balance.

• Using more than 30% of the available limit on any card can hurt your credit score. “Maxing out” your cards can lead to higher interest rates and penalties.

• Credit card issuers have invented a number of ways to “ding” their customers even if they don’t carry a balance. Read the disclosures your issuer sends you and consider some kind of automatic payment system so you’re never late.

Shopping Tips

• If you’re carrying a balance, look for a card with a low, fixed rate. Use a separate card for any new purchases, and pay it off in full each month. Better yet, use cash.

• Don’t keep bouncing balances from card to card. Use low-rate offers to help you pay down your debt.

• If you don’t carry a balance, consider a rewards card. The best one for you depends on your spending patterns and goals, so do your research.