4. Mortgages

At the peak of the real estate bubble, I heard from a lot of people who were absolutely convinced that real estate prices could not go down. “They’re not making any more land!” was their usual refrain.

I knew better because I’d already lived through two regional real estate recessions—one in Alaska and another in Southern California. Until you’ve experienced dropping prices and soaring foreclosure rates, it can be hard to imagine how quickly a real estate boom can unravel.

Well, now we all know better. After peaking in the summer of 2006, home prices nationwide dropped by 34% by the spring of 2012, as measured by the S&P/Case-Shiller 20-city index. The devastation was even worse in parts of Florida, Nevada, Arizona, and California, where values fell by 50% or more.

As with previous real estate busts, an initial spike in defaults led lenders to slash prices to dump foreclosed houses quickly. That drove down the value of neighboring houses, wiping out equity of other, often overextended borrowers. These homeowners became more likely to walk away from their homes—leading to more fire sales and further depressing values.

Potential buyers got cautious. People who could afford to buy homes put off the purchase, waiting for prices to stabilize. Those who did want to buy found lenders had become extremely conservative about who could get loans. Those trends reduced demand for homes and pushed prices even lower.

People who expected real estate to make them rich, or at least fund their retirements, found themselves deeply underwater, owing more on their homes than those properties were worth. Many struggled with outsized mortgages that never should have been made; others found their mortgages became unaffordable after they lost their jobs in the recession caused by the mortgage mess.

There are signs that the worst of the housing recession has passed. Prices are starting to rise, however modestly, in many areas. The devastation of the past few years hasn’t soured most people on homeownership: The majority of U.S. households are homeowners. The question remains, though: Is home-ownership right for you?

Here’s what I wrote in the first edition of this book in 2005, and it’s still true today:

Owning a home can be a good way to build wealth over time. Homeowners typically benefit from rising real estate prices, and many (although far from all) get tax breaks to help subsidize the cost.

But homeownership isn’t right for everyone in all circumstances, and finding the right mortgage can be an incredibly tricky affair. You can easily find yourself paying too much for both your house and your loan. In the worst-case scenario, you could be setting yourself up for foreclosure and financial ruin.

Getting good, objective information on home buying and mortgages is tough, however. There are a lot of myths and outdated information. The people who tend to know the most about these transactions—real estate agents and lending professionals—usually have a financial stake in your decisions, which should make you at least somewhat skeptical about whether they have your best interests at heart.

Once you’ve got your mortgage, your decision making isn’t over. You’ll probably be bombarded with offers to help you refinance or pay off the loan early. These solicitations can sound incredibly good, but at best they give you only part of the story, and in the long run they may hurt you financially.

This chapter should help you answer the following questions:

• Should I buy a house?

• How much house should I buy?

• What kind of mortgage should I get?

• How do I get a good mortgage deal?

• When and how should I refinance?

• When should I prepay a mortgage?

First, we need to bust some of the myths that cloud people’s thinking when it comes to home buying.

Myth #1: It’s a Good (or Lousy) Time to Buy a Home

Interest rates are low. Home prices have recovered from their bottoms in many areas, but are still well below their peaks. Surely now is the time to land a bargain, right, because prices have nowhere to go but up?

Not according to the naysayers. They can explain away any signs of improvement in real estate markets and warn of further debacles to come. The more apocalyptic among them paint a picture of a decades-long economic downturn and home prices that never return to their former levels.

Here’s the reality: Trying to time any investment market is usually a loser’s game. The best time to buy a house is when you’re ready to buy one, when you can afford the costs, and when you’re planning to stay put for awhile. That was true during the boom, it was true during the bust, and it’s still true now.

Myth #2: A House Is a Great Investment

Financial planners will tell you that you shouldn’t think of a house the same way you think of other investments, like stocks, bonds, or mutual funds. Here’s why:

• Big emotions. A house is where you live, love your partner, and raise your children. You’d be a strange bird indeed if you felt the same attachment to a stock as you did to the place you call home.

• Big transaction costs. You can buy and sell securities with relative ease and at little expense. By contrast, you may need months to sell a home. The seller typically pays a 6% commission to the real estate agent who handles the sale, while other selling and moving costs often add another 4% or so to the toll. That means 10% of the value of your home disappears each time you sell and move.

• Big carrying costs. Your mutual fund will never require you to cough up $10,000 to buy it a new roof. The so-called “carrying costs” of homeownership are enormous. They include mortgage interest, insurance, taxes, maintenance, repairs, and improvements.

Many homeowners, however, forget to subtract these costs when they measure the financial gain they’ve experienced over the years.

If you had bought a house for $35,000 in 1970 and sold it in 2010 for $200,000, for example, you may think you’ve earned a whopping gain. In reality, you’ve only matched the rate of inflation during those years, plus you may have paid out more than $100,000 along the way in repairs, maintenance, and improvements.

Failing to beat inflation is actually the norm. Except for a short period after World War II and again during the boom of the 2000s, home prices nationwide just managed to match the rate of inflation, according to the economists behind the Case-Shiller index, Robert J. Shiller and Karl E. Case.

What’s more, a study commissioned by The Wall Street Journal in 1998 found that the price of keeping a typical home up to current standards over a 30-year period is almost four times the home’s purchase price. Add to that sum the amount you shelled out over the years for mortgage interest, property taxes, and insurance. Viewed that way, you probably lost financial ground.

Homeownership does help people build wealth, though, even when their home prices don’t go through the roof.

Most mortgages require you to pay down your balance over time. That’s a kind of “forced savings” that helps you build equity over the years, even if home prices rise only modestly.

Many also believe the act of becoming homeowners helps people become more responsible with their money and more interested in other ways they can build wealth. In other words, you might be more likely to invest in your 401(k) and buy other assets that increase in value over time, rather than blowing all your money on consumables like cars, clothes, and cuisine.

So, yes, a house can be a great investment. But it isn’t a slam dunk.

Myth #3: Buying Is Always Better Than Renting

How many times have you heard someone say, “I had to buy a house because I was tired of throwing away money on rent?”

The reality is that you’re not tossing cash out the window when you rent. You’re buying freedom and flexibility, things you give up when you become a homeowner. Just hear what Alice had to say:

“I owned a home for five years and got rid of it when I realized the home owned me,” she wrote. “Getting reliable people for maintenance and repairs was a major hassle. Scheduling maintenance and repairs meant staying home from work and waiting for people who sometimes didn’t even show up. I am now an apartment dweller and figure the rent pays for all maintenance and peace of mind.”

The benefits of renting go far beyond having a landlord to do the dirty work. If you lose your job, or the area starts to deteriorate, or you hate your neighbors, you can move pretty easily, compared with the costs and delays you’d face as a homeowner.

You may face rising rents. But homeowners face rising taxes and maintenance costs.

Renting is almost always the best option if you plan to be in an area for less than three years. Typically, it takes at least that long for home price appreciation to cover your selling and moving costs. It may take less in a superhot market—or it may take much more if home prices continue to fall.

Myth #4: Homeownership Comes with Great Tax Breaks

It’s true that mortgage interest is potentially deductible on your tax return, as are the property taxes you pay. But many people overestimate the extent of those tax breaks and often misunderstand how they work.

Mark is an attorney in Frederick, Maryland, who shared many people’s misconceptions about the potential tax benefits of homeownership.

“Homeowners get 100% of their interest payments back on their annual tax returns, right?” he wrote. “If I accumulate principal with each mortgage payment and get all of my interest back when filing my taxes, then it does compare favorably to renting, doesn’t it?”

In reality, the amount of your tax break is limited to your tax bracket. If you’re in the top federal tax bracket (35% in 2012), every dollar you pay in mortgage interest saves you at most 35 cents in federal income taxes. If you’re a middle-income taxpayer, your savings might be 25 or 15 cents per dollar spent.

That’s why it’s so absurd when people consider, or actually obtain, mortgages because they “need the tax break.” Where else would you give someone a dollar just to get 15, 25, or 35 cents in return?

And that’s the best-case scenario. In reality, the tax break you’ll actually get will be much less—or even nonexistent.

Here’s the reality:

• About half the nation’s homeowners get no tax benefit. To get any tax break from a home, you have to have enough deductions to itemize. Two thirds of the nation’s taxpayers don’t, so they take the standard deduction. Some of these people own their homes outright, but many don’t pay enough mortgage interest and property taxes to be able to itemize.

• The tax break is less than you think. Even if you can itemize, the tax break you get from homeownership only equals the amount by which your write-offs exceed the standard deduction, as I explained in Chapter 2, “Your Debt Management Plan.”

For example, a single person in 2012 got a standard deduction of $5,950—even if he rented and had no other potentially deductible expenses. If he paid $7,000 in mortgage interest that year, the only advantage he would have over a renter who paid no mortgage interest is an extra $1,050 in deductions. In the 25% tax bracket, that $1,050 extra in deductible interest is worth just $262.50. So instead of saving 25% on his taxes, his actual tax break compared with the amount spent on mortgage interest is less than 5% ($262.50 divided by $7,000).

Of course, he might pay much more in mortgage interest, and have other potentially deductible expenses that he’s only able to write off because he has a mortgage. If he paid $2,000 in property taxes, for example, that would boost his “extra” deductions to $3,050 and boost his tax savings to $762.50. But that’s still less than 10% of the $9,000 he spent.

The fact that you’d get $5,950 in “free” deductions (or $11,900 for a married couple), whether or not you spent a dime in mortgage interest, significantly reduces the effective tax break for most homeowners.

• The tax break tends to disappear. Most mortgages are “front-loaded” so that you pay the most interest in the first year and a little less every year after that. The standard deduction, by contrast, increases every year to at least match the rate of inflation. The combination of the two trends means that many middle-class couples who get any benefit at all lose the tax break within the first 10 years.

And remember all those other house-related expenses I outlined earlier, such as insurance, maintenance, and repairs? Those are never deductible on a primary residence.

The Right Reasons to Buy

So if none of these myths are a good reason to buy a house, what is?

First and foremost, you have to want to be a homeowner. It doesn’t matter what your parents think or your friends advise or your tax guy suggests. If you aren’t ready, you aren’t ready.

That was the case for Richard in Raleigh, who wrote me about an article I wrote for MSN on the home-buying myths.

“I am getting tremendous pressure from my tax advisor and other folks to purchase a home, but after reading your column, it is for all the wrong reasons,” Richard wrote. “Clearly, I am not ready to purchase a home, and this article helped solidify my decision.”

If the following statements are true, buying a home can make sense:

• I plan to stay put at least three years and probably more. In a typical market, it can take three to six years for a home to appreciate enough to offset the costs of selling and moving. If you’re in a particularly hot market—one that might be ripe for a correction—your desired time frame might be even longer because it could take many years for prices to recover.

• I’m psychologically prepared. Renting is like dating, home ownership is like marriage, and not everyone is cut out for wedded bliss. Even if you can unclog your own drains, you’ll still occasionally have to call a plumber, as well as take responsibility for all the other chores your landlord handles now.

• I have some extra savings. It’s a rare first-time homeowner who isn’t shocked by how much money she spends on repairs, maintenance, and decorating in the first years in her home (not to mention how much time you spend at Home Depot!). Those who drained their savings buying the house can find themselves going deeper and deeper into debt. You’d be much smarter to make sure that after the deal closes, you still have savings equal to at least three months’ worth of mortgage payments, and preferably much more.

• I manage my money pretty well. That “forced savings” aspect mentioned earlier works only if you can resist the temptation to drain your wealth with home equity loans and lines of credit. If you’re carrying credit card debt now, and you’re not quite sure what’s happening to all the money you make, put off your house search and clean up your financial house first.

Otherwise, you’ll wind up like some of the clients that Kevin, a financial planner, sees in his Atlanta practice.

“One of the most eye-opening aspects of starting my practice and having prospects and clients share their financial secrets with me is the horror I see when folks get caught in the perpetual cycle of trading equity in their home to pay off consumer debt,” Kevin wrote. “When I see how so many folks are highly leveraged with home equity lines of credit or interest-only loans, I think to myself, ‘They might as well be renting.’”

How Much House Should I Buy?

If you’ve decided you’re ready, you still need to decide how much mortgage you’re willing to take on.

Again, this is not a decision you should put in the hands of your lender, your real estate agent, your family, or your friends. Chances are good none of these folks know what you can really afford. Your lender or agent may know every detail of your current financial life, for example, but he or she probably doesn’t know when you want to retire, how many children you want to have, or how much you like to travel—all factors that influence how much of a mortgage you should take on.

It’s true that lenders are far less likely to saddle you with an unaffordable mortgage than they were a few years ago. At the peak of the madness, lenders approved mortgages that ate up as much as 60% of the borrower’s income. Interest-only and “pick a pay” mortgages were common, which meant many people weren’t paying down their debt. In some cases, their mortgage balances were rising. Borrowers may not have had to prove their income or assets, leading to “liars’ loans” that were far bigger than the homeowner could possibly afford.

Still, with a steady income and good credit scores, you can still get a mortgage with a payment that exceeds 30% of your income—even though that may not leave you with enough left over to save for retirement or pursue other financial goals.

The idea that it’s okay to stretch to buy a home made sense 30 or 40 years ago, but it doesn’t make sense today. Prices soared in the 1970s and early 1980s—and so did wages. Those big jumps in income made mortgage payments feel substantially smaller every year, so even those who overdid their debt felt pretty comfortable within a few years. Today, you can’t count on double-digit income boosts to bail you out.

Inflation isn’t the only factor affecting incomes that’s changed. Forty years ago, more families were supported by a single income—which means that if the breadwinner lost his or her job, the other spouse could go to work to help save the house. When you need both paychecks to cover the mortgage, there’s no one in reserve to take up the slack, and a job loss can quickly lead to foreclosure.

Saving for retirement is also a bigger issue today. A far larger percentage of the workforce had traditional, defined-benefit pensions 30 or 40 years ago. That means they didn’t have to put aside big chunks of their paychecks for 401(k)s and IRAs if they wanted to have a decent retirement. Chances are good that you don’t have a traditional pension, so if you don’t save, your retirement could be pretty grim.

So how much should you spend on a house? Many financial advisors recommend capping your housing costs at 25% of your gross (or total, pretax) income. That limit would give most families enough maneuvering room so that they can save for other goals without becoming overly indebted or “house poor.”

Consider an even lower limit if

• You want kids. Children are wonderful, but they’re also a drain on budgets. Bankruptcy expert Elizabeth Warren of Harvard University says just having kids is one of the leading predictors that a family will end up declaring bankruptcy. If you want to avoid that fate—and have the freedom for one parent to stay at home for a while—don’t opt for an oversize mortgage.

• You have expensive habits. If you love to travel—or restore sports cars, or breed horses, or pursue any number of pricey hobbies—leave enough room in your budget to follow your passion. Most people are willing to cut back to afford the home they want, but if you’re not, buy less house.

• Your income’s all over the map. Most people have variable incomes because of overtime pay, bonuses, and commissions. But if yours really is unpredictable, you might want to base your home purchase on the minimum you expect to make each year.

You may be able to boost your limit higher if

• You’re debt-free. The 25% cap assumes that you have at least some other debt: car loans, student loans, credit card balances. If that’s not the case, you can probably stretch further.

• You don’t have to save much for retirement. Government employees and public school teachers tend to have very good pensions that may replace 60% or more of their incomes in retirement. If you don’t have to save a small fortune for your golden years, you can afford to throw more at a house.

• You’re on the fast track. Some people have a pretty good shot at much higher incomes in just a few years. If you’re currently a public defender and you’re about to join a private practice, for example, you can expect your income to spike, so stretching a bit now might work out all right.

What Kind of Mortgage Should I Get?

Some of the most toxic mortgages have all but disappeared from the market, fortunately. But you still have more choices than your grandparents did. Before the 1980s, mortgages came in one basic flavor. The rates were fixed, you paid them back over 30 years, and then you held a mortgage-burning party where you triumphantly set fire to your loan paperwork.

Spiking interest rates in the 1980s brought adjustable-rate loans, where borrowers got low “teaser” rates in exchange for the possibility that their payments would change with interest rate swings.

Today, one of the more popular options is the hybrid loan, which combines features of both fixed and variable rates. Typically, the loan is fixed for the first three to seven years before becoming adjustable.

Adjustable and hybrid loans initially offer borrowers lower payments than they’d get with a 30-year loan—sometimes much lower. But all expose borrowers to the risk that their payments will rise, perhaps sharply, in the future.

At the other end of the scale are short-term, fixed-rate loans that help you pay down your principal faster. As interest rates plummeted to levels not seen since the 1950s, many borrowers refinanced into 15-year fixed-rate loans so that they could own their homes free and clear in half the time of a traditional mortgage.

So, how in the world do you decide what’s right for you?

There’s no one right answer. It all depends on your plans, the prevailing interest rates, and your tolerance for risk.

There’s a lot to be said for the traditional 30-year mortgage. Your interest rate is fixed for the life of the loan, so you don’t have to worry about rising payments. If rates drop, you can always refinance. Meanwhile, you’re paying off a little principal with each payment, that “forced savings” that helps you build wealth over time. Payments are lower than for a loan with a 15-year term, which can give you more financial flexibility. If you want to pay more toward your principal, you can, but you’re not locked into higher monthly payments.

All that flexibility and stability comes at a price, however. Interest rates and monthly payments on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages will be higher than with many of your other options.

That’s why many mortgage experts traditionally said you should match your mortgage to the length of time you expect to be in your home. Someone who plans to move in five years, for example, would be advised to choose a five-year hybrid loan or even an interest-only loan where the rate is fixed for the first five years.

The thinking is that even if you stay a year or two longer than you expected, you’ll still save money compared with what you would have spent with a fixed-rate loan.

Of course, that advice assumed you’d be able to move on—that you wouldn’t be trapped into your home by falling prices and negative equity.

Short-term adjustable-rate loans are an even bigger gamble. You know the payment will go up because you’re paying a low “teaser” rate for the first few months that will eventually adjust upward to the “regular” rate. What happens after that depends entirely on what’s going on in the economy and with the Federal Reserve, which controls short-term interest rates. In the past several years, the Fed has been fighting the economic downturn with extremely low rates. If the economy picks up and inflation results, the Fed could raise rates abruptly to fight that threat.

Most adjustables come with built-in safeguards. Typically, the rate isn’t allowed to rise more than 2 percentage points a year, or 6 percentage points over the life of the loan.

But that’s still a pretty big potential rise. An increase from 3% to 8%, for example, would nearly double the monthly payment on your mortgage.

The risk on interest-only loans is even greater, which is why these mortgages are much harder to get than they used to be. Although many interest-only loans offer fixed rates initially, they usually change to variable loans after a number of years. At some point, the loan also will require you to start making principal as well as interest payments.

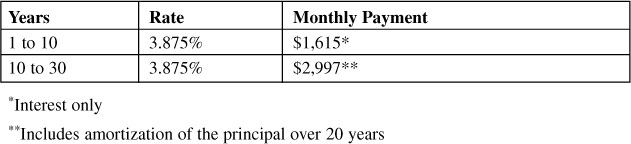

This can lead to huge payment shock. Instead of paying principal over 30 years, you’re typically paying principal over 20 years or less. Table 4.1 shows what you might see with an interest-only $500,000 loan where the principal payments are required starting with year 11.

This example assumes the absolute best-case scenario: Interest rates stay exactly the same—and near record lows. Neither is likely.

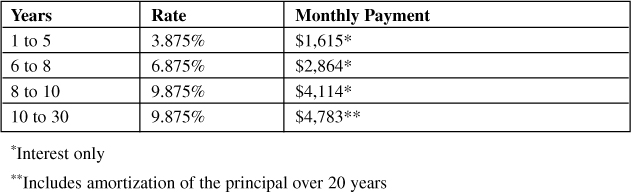

Table 4.2 shows a more frightening example in which interest rates increase to the loan’s caps over the years. The first five years have a fixed rate, the second five have a variable rate that starts at 6.875%, and the final decades have the highest rate allowed, plus principal payments starting in year 11.

Table 4.2. Interest Rates Increase to the Loan’s Caps

Most likely, your experience with an interest-only loan, or any kind of hybrid or adjustable, would be somewhere between the extremes. But you should at least know how bad things might get before you make the choice.

When people get into trouble is when they choose an alternative mortgage because it’s the only way they can purchase the home they want to buy. At some point, their payments will rise, and they may be forced to sell prematurely if they can’t afford the increased cost.

When you’re evaluating loans, take the following steps:

• Do the math. Make sure you calculate exactly how high your monthly payment can go if you opt for anything other than a fixed-rate loan. If you don’t know how to do the math, look online for a mortgage amortization calculator or ask your mortgage broker or lender to help. Don’t accept the loan officer’s blandishments that a variable-rate loan will “never” reach its caps. Nobody can predict the future of interest rates, and people have been surprised before. Make sure you’ll be able to swing the higher payments or be willing to sell your house if worse comes to worst.

• Consider your need for financial flexibility. If your income is quite variable or you expect heavy expenses like college tuition payments in a few years, be careful about taking on a loan with payments that could spike. Many people choose an adjustable or hybrid loan for the low initial payments, only to find themselves trapped when payments rise.

• Evaluate your tolerance for risk. You may be willing to literally “bet the house” that interest rates will stay stable or that your income will rise sufficiently to manage higher payments. But if that’s not the case, there’s nothing wrong with opting for the safety of a fixed-rate loan.

• Don’t expect to refinance your way out of trouble. Far too many homeowners during the boom believed lenders who told them that they could refinance a high-risk loan into a fixed-rate one down the road. That optimistic view assumes everything goes right—that values go up but interest rates don’t, for example, and that your income and credit scores don’t drop. Also keep in mind that rates on variable and fixed-rate loans tend to rise and fall at about the same time. If your variable-rate loan payments shoot up, chances are good that the payment on a fixed-rate loan would be even higher.

How Do I Get a Good Mortgage Deal?

Figuring out which loan you want is just the start of the challenges you’ll face. Finding and applying for a mortgage—and not getting soaked in the process—isn’t easy.

You’ll face stunning amounts of paperwork, fees that appear from nowhere, and a whole glossary of new terms to learn. It’s easy for novices and even more-practiced homebuyers to stumble.

Fortunately, you have plenty of resources to help you through the process. Two of my favorites are Mortgages for Dummies and Home Buying for Dummies, both by Eric Tyson and Ray Brown.

Here are a few suggestions to help you navigate and get the best possible loan:

1. Fix Your Credit

Pull your credit reports from all three bureaus at least three months—and preferably six months—before you apply for a mortgage. The information on your reports determines your all-important credit scores, and you’ll want to have time to correct any significant errors.

Most people can improve their standing by paying down debt, paying all their bills on time, not closing accounts and not applying for credit they don’t absolutely need in the months before they shop for a mortgage. (For more information about credit scores and combating credit report errors, see my book Your Credit Score: How to Improve the 3-Digit Number That Shapes Your Financial Future [2011, FT Press].)

2. Understand Points and Fees

The interest rate is just one part of the mortgage puzzle. To shop effectively for a loan, it’s also important to know what you’ll be paying in points and fees.

A point is a percentage of the loan amount: One point equals 1%, or $2,000 on a $200,000 mortgage. People pay points to get a lower interest rate. One borrower might pay no points to get a 5% rate, for example, while another might pay one point to get a 4.75% rate. The longer you plan to be in your house, the more you might want to consider “buying down” your rate.

Fees are what lenders charge to process your loan. Lenders are supposed to provide you with a “good-faith estimate” of these charges within three days of your application, but many let you know up front what their closing costs are likely to be.

One particular fee you might want to ask about is the cost to “lock in” a rate. If rates rise between the time you apply and the time the loan closes, a lock can ensure that you get the original rate. But you should know how much this guarantee costs and how long it lasts.

Don’t believe anyone who tries to sell you a “no-cost” mortgage. Loans always have costs, although they can be disguised as a higher rate or as fees that are added to your principal.

3. Shop Around for Rates and Terms

Thousands of lenders are out there, competing for your business. Don’t just assume you’ll get the best deal from the first one you call.

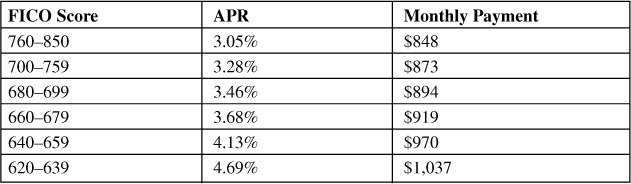

Once you know your credit score, you can find out what kinds of rates you can expect (see Table 4.3). The Loan Savings Calculator at MyFico.com gives you an idea of prevailing rates for people with scores similar to yours.

Table 4.3. Mortgage Rates by Credit Score for a 30-Year $200,000 Loan (Duplicate of Table 2.2)

Source: MyFico.com and Informa Research Services

During the real estate boom, too many people with good credit got stuck with loans meant for people with lousy credit. These “subprime” loans were more profitable for the lenders and the brokers, so less ethical mortgage professionals pushed them over loans that give you a better deal.

Many borrowers are also sideswiped by last-minute charges and fees they hadn’t anticipated. That’s why it’s important to ask about points and fees up front and to deal with reputable brokers and lenders who don’t dish up unpleasant surprise charges to their customers.

If you’re comfortable using the Internet, you can visit sites like Quicken Loans and LendingTree to get competitive offers from lenders. The nice thing about these sites is that fees are disclosed up front, which makes shopping easier.

Otherwise, you can call various lenders or get a mortgage broker to help you do your shopping. Brokers typically have access to a wide variety of lenders and loan programs. (Brokers can be particularly helpful if you’re wading into the mortgage pool for the first time or if you have unusual circumstances, like bad credit.) Get referrals from friends and make sure the broker is experienced and is a member of the National Association of Mortgage Brokers, which has ethical and education standards.

One note: You’ll want to do your mortgage shopping in a concentrated period of time—preferably within two weeks. Lenders typically pull your credit reports and scores before making their offers, and all those inquiries could wind up hurting your score unless they come fairly close together. The latest versions of the FICO credit scoring model treat all mortgage-related inquiries made within a 45-day period as one inquiry. Some lenders, though, may use older versions of the formula that aggregate inquiries within a two-week period.

4. Check out First-Time Homebuyers’ Programs

These programs are usually sponsored by state, county, or city governments and typically offer better interest rates and terms than most private lenders, said mortgage expert Diane St. James of ABC Mortgage Consulting.

Many state housing agencies, for example, offer loans with below-market interest rates as well as programs that lend or give you cash for a down payment. And you don’t have to be poor to get help; in high-cost areas like Boston, a family of three could have a six-figure income and still qualify for the state’s MassHousing program.

These programs have some hitches. If you sell within nine years of getting the loan from a state agency, a federal tax could take back up to 50% of any profit you make on the home. (For more information, contact the National Council of State Housing Agencies at www.ncsa.org.)

5. Get Preapproved for a Loan

If you’re buying a home (rather than refinancing), you’ll want to get preapproved for a loan.

Many first-time borrowers think “prequalified” is the same as “preapproved,” but it’s not. Prequalification is a pretty informal process in which a lender gives you a ballpark idea of how much it might lend you based on what you tell it about your income, your debt, and how much cash you have on hand.

Preapproval, by contrast, is a much bigger commitment. You usually have to submit tax returns, pay stubs, and other proof of your financial situation. The lender verifies the information and checks your credit before making a written commitment to make the loan.

If your real estate market is at all competitive, you’ll want to put yourself in the best position to have your bid accepted. That’s why you need to be preapproved—you’re showing that a lender has checked you out and committed to make the loan. That’s a lot more attractive to a seller than a buyer whose lender might simply back out.

6. Don’t Pay Junk Fees

If you ask many mortgage brokers or lenders, they’ll tell you there’s no such thing as a junk fee—that everything listed on the good-faith estimates they’re required to give to loan applicants is a legitimate charge.

Legitimate or not, many of these charges are quite negotiable. Entries such as “document preparation,” “administration,” and “processing” are mostly pure profit and can be winnowed out. Also look for padding on third-party charges, like credit checks; these shouldn’t cost the lender more than a few bucks, but some try to zap you with a $150 fee. Ask about any charge you don’t understand, and try to negotiate any charges that seem excessive. You’ll want to do your negotiating up front. If the lender or broker won’t play ball, take the written estimate to another shop, St. James recommends. This is a competitive industry, and the borrower should be in the driver’s seat. Lenders are now required to use a standardized form to disclose estimated costs. That makes it easier than it used to be to compare offers, apples-to-apples.

The new good faith estimate forms distinguish between fees the lenders control and those that come from third parties. Lender fees consist of two items: points paid to reduce the interest rate, if any, and the total of all other charges, known as adjusted origination charges. It’s the latter that should be the focus of your comparisons.

Lenders are now limited in how much they can change origination charges between the time they issue a good faith estimate and the time they close the deal. That has reduced the number of unpleasant last minute surprises borrowers face, but you should still carefully compare the two documents before you sign.

7. Plan for Closing Costs

At closing, you’ll be expected to write a sizeable check for a number of costs, including things like attorney’s fees, taxes, title insurance, prepaid homeowners insurance, points, and various other fees. These closing costs can be fairly substantial. A recent survey by Bankrate.com found closing costs nationwide on a $200,000 mortgage averaged $4,070, with the amounts ranging from an average $3,378 in Arkansas to a whopping $6,183 in New York.

Your good-faith estimate should give you an idea of how much cash you’ll need in your checking account. But make sure these costs don’t clean you out. Too many people deplete their savings to buy a house and then wind up in debt—or even unable to pay their mortgage—when the furnace conks out or some other inevitable expense pops up.

You should plan to have at least three months’ worth of mortgage payments in cash after closing, preferably tucked away in a safe, liquid place like a savings account or money market fund.

When and How Should I Refinance?

Your first mortgage almost certainly won’t be your last. The typical homeowner keeps a mortgage for less than seven years before moving or refinancing. That holding period can be considerably shorter when rates are dropping and homeowners rush to exchange their loans for something cheaper.

Knowing when you should refinance is getting tougher. The old rule of thumb was that interest rates had to drop a full 2 percentage points for a refinance to make sense for most people. But that was back when everybody had 30-year fixed mortgages and refinancing costs were high.

Today there are so many different kinds of mortgages and so much competition driving down costs that rules of thumb don’t really work anymore. You really need to take a good look at your individual situation and what lenders are currently offering.

Here’s how to know if you should refinance:

• Figure out what you really want. Are you just trying to lower your monthly payments? Or would you like to pay off your home faster? Are you looking to get cash to pay for a home improvement or other project? Your goal will help determine the kind of loan and costs you’ll face.

Sometimes you can accomplish more than one goal. Super-low interest rates allowed some people to dramatically shorten their loans while keeping their monthly payments about the same. But most of the time, you’ll have to decide which goal is most important, and this will dictate the kind of loan you’ll be shopping for.

• Run the numbers. Use the earlier advice about shopping for a mortgage to get a clearer idea of how much refinancing will cost you, and then use one of the mortgage refinancing calculators available on the Web to crunch the numbers. (You can find a good one at www.hsh.com/usnrcalc.html.) This will show you your “breakeven” point: when (or if) the savings from the new loan will offset the costs of refinancing.

If it’s three years or less, and you’re sure you’ll be in the house that long, you can consider going ahead. Any mortgage refinance with a breakeven point more than three years out is a risky proposition because chances increase that you’ll sell the house before you recoup the costs.

In fact, some mortgage experts say you should be cautious if the refinance will take more than 18 months to break even.

Here are some other signs that you’re better off not refinancing:

• You’ve been paying the loan for several years. By the time you’re 10 or 20 years into a 30-year loan, for example, much of your payment is going toward principal. Refinancing to another 30-year loan would probably just increase your costs in the long run.

• Your credit has deteriorated significantly. Have you missed payments, maxed out your credit cards, or suffered a serious hit to your credit report, such as a repossession, collection, or judgment? Worse yet, have you filed for bankruptcy? You may not be able to get a rate low enough to justify refinancing.

• You’ve stripped all the equity out of your house. To get the best rates, you’ll need to keep your borrowing to less than 80% of the value of your home. You’ll have a tough time finding a willing lender if your home debt equals 90% or more of your home’s value.

• You’re facing a substantial prepayment penalty. Prepayment penalties aren’t as common as they used to be, but some mortgages still punish you if you refinance within a certain period. You might not realize you agreed to a prepayment penalty when you got your loan—you’ll need to check your paperwork.

David in Illinois missed out on some of the lowest rates in a generation because of just such a clause.

“When we tried to refinance, we found out there was a huge penalty to pay back more than 20% of the remaining balance in a 12-month period,” David said. “Needless to say, we couldn’t refinance because the penalty would have meant almost an additional $5,000.”

There’s one more issue to think about. If you keep replacing one 30-year mortgage with another, you’re putting off the day when your payments will significantly build your equity. Instead of building wealth by paying down your debt, you’re basically “renting money” from the bank.

Some financial pundits insist that’s a smart move. They think everybody should stay in perpetual mortgage debt. Their reasoning is that mortgage loans are cheap money and that you can get better returns on your cash elsewhere.

I agree with that view—to a point. I think most people want to have their home paid off by the time they retire. When you’re on a fixed income, having a paid-off house can give you enormous peace of mind. Not having a mortgage to pay also can reduce the amount of money you need to withdraw from retirement funds, which can help make your nest egg last longer (and usually lower your tax burden in the bargain).

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t refinance if you’re over 40—just consider a shorter loan. If you’re five years into a 30-year mortgage, for example, think about refinancing to a 25- or 20-year loan. That way you can lower your monthly payments without extending your time in debt.

When Should I Prepay a Mortgage?

Zach in Lake Forest, Illinois, was intrigued by the offers he got in the mail to help him pay off his mortgage faster.

These services offer to help you set up a biweekly payment program to shave your loan costs. Rather than pay $1,199 a month on a $200,000 mortgage, for example, Zach would pay $599.50 every two weeks. Since there are 52 weeks in a year, he’d be making 26 half-payments—the equivalent of 13 full payments, or one more payment than he would otherwise make.

The biweekly plan, the service promised, would shave five years and $47,282 in interest off the cost of a 30-year mortgage, assuming it had a 6% interest rate.

“Is this any different from just prepaying that one extra payment per year?” Zach asked in an e-mail. “The reason I ask is there is a $400 enrollment fee [for the service], and it seems math-wise that I could do the same thing paying a few hundred dollars extra each month.”

Zach’s right—the effect of making 26 half-payments or 13 full payments is basically the same. If you opt to prepay your mortgage, you don’t need to pay anyone to set up the system. You can either set the money aside throughout the year to make an extra payment, or add a bit to each mortgage payment to get your loan paid off faster. (Just make sure the lender knows the extra money is for principal repayment.)

Before Zach or anyone else sets up such a plan, he needs to take a good look at the state of his finances and make sure all his other bases are covered.

It makes no sense, as I said earlier, to prepay a low-rate mortgage when you’ve got high-rate debt accumulating interest elsewhere. Generally, a mortgage is the very last debt you’ll want to pay off, tackled only after all your other bills—credit card debt, auto loans, student loans, whatever—have been retired.

You’ll also want to make sure you’re taking full advantage of your tax-deferred retirement options, like contributing the maximum to your company’s 401(k)—particularly if it has a match. The returns you’re likely to get in those plans far exceed the returns you’ll get from paying off a mortgage.

You’ll want to check to make sure your loan doesn’t have prepayment penalties; unfortunately, some do.

Finally, you’ll want to follow your mortgage lender’s instructions to the letter about how to get extra payments applied to your principal. Some people have discovered, to their horror, that their extra money was applied to the next month’s bill and didn’t reduce their principal at all.

Summary

Homeownership can help build your wealth, but you can easily end up paying too much for your house and your mortgage.

Credit Limits

• Buy a home when it’s right for you. Don’t be persuaded by common myths about homeowning or be pressured into a purchase when you’re not ready.

• Try to cap your housing costs at 25% of your gross income to give yourself some financial flexibility.

• Consider matching your mortgage type to the length of time you expect to be in the house. But don’t automatically discount the traditional 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage, which offers stability and flexibility for many buyers.

Shopping Tips

• Refinance when it makes sense for your particular financial situation. There are no rules of thumb; the decision rests on your goals, your credit situation, how long you’ve been paying your current mortgage, and how long it will take to recoup your costs.

• Know all the costs that come with a mortgage—the interest rate, the points, the fees—and shop hard. Thousands of mortgage lenders out there are ready to compete for your business; don’t assume you’ll get the best deal from the first one you call.

• Don’t pay someone to set up a prepayment plan for you. And accelerate mortgage payments only when the rest of your financial bases are covered.