5. Home Equity Borrowing

The dangers of squandering your home equity—a long-term asset—on short-term spending were obvious even before home prices plunged. Yet every time I wrote articles for the MSN Money site warning consumers not to tap their equity to pay for stuff like vacations, big-screen TVs, and credit card debt, the articles were accompanied by big ads from lenders urging consumers to do just that.

Some readers saw the irony and sent me e-mails about the contrast between my sober admonitions and the “Borrow! Borrow! Borrow!” siren song of the ads. But too many missed the advice altogether and succumbed to lender suggestions that they treat their homes like piggy banks.

Doing so dramatically increased the chances they wound up underwater on their homes. Nearly 40% of homeowners who took out a second mortgage eventually owed more on their homes than they were worth, according to a 2011 report by real estate research firm CoreLogic. Among homeowners who didn’t have home equity loans or lines of credit, just 18% were underwater.

Yet even now—incredibly—you can still hear the argument that people should put their home equity “to work” for them. One man told me his financial advisor (actually an insurance salesman) urged him to borrow from his home to buy an expensive whole-life insurance policy. Another attended a real estate investment seminar where people were advised to use as much of their home equity as possible to buy foreclosures. Savor the irony of that suggestion: The seminar leader was telling people to do what may have gotten the foreclosed homeowners in trouble in the first place.

There are cases where a home equity loan or line of credit can be a smart solution. But too often it’s used to fuel unwise spending.

The Dangers of Home Equity Lending

Home equity lending exploded during the real estate boom. New borrowing grew by nearly four times in five short years between 1999 and 2004. By 2008, when the wheels started coming off our economic bus, Americans had borrowed more than $1 trillion in home equity loans and lines of credit.

Less than a third of all this borrowing, lenders say, was used for anything that could remotely be considered an investment, such as home improvements or education. The rest went for debt consolidation, vacations, or purchases of assets that quickly depreciate, such as cars. Even families of modest means and troubled credit could leverage their homes into a steady stream of consumption.

This was a big change from generations earlier, when people strove to pay off mortgages early and held mortgage-burning parties. Back then, having a second mortgage on your property was something of a stigma.

The change in attitudes was orchestrated by bankers, who realized that they could make a lot of money if they could persuade people to borrow against their equity. Here’s a quote from a New York Times article that ran in 2008, as default rates on these loans were starting to rise:

“Calling it a ‘second mortgage,’ that’s like hocking your house,” said Pei-Yuan Chia, a former vice chairman at Citicorp who over-saw the bank’s consumer business in the 1980s and 1990s. “But call it ‘equity access,’ and it sounds more innocent.”

The banks spent billions on advertising to change attitudes. Citicorp adopted the slogan “Live Richly,” despite some executives’ concerns that it might encourage people to live above their means. A PNC Bank ad included a wheelbarrow with the slogan “easiest way to haul money out of your house.” A Fleet ad offered the advice, “The smartest place to borrow? Your place.”

Then the credit crunch began. I remember getting an e-mail from a reader in late 2007 who said his lender had frozen his home equity line of credit. His tale was such an anomaly that I started calling around to my various mortgage sources, asking if they had ever heard of such a thing. At that point, they hadn’t.

That would quickly change. As the mortgage mess unfolded, lenders that were once desperate to get us to borrow against our equity were now desperate to minimize their exposure to coming losses. Home equity lines of credit were frozen or reduced with no warning, sometimes leaving people stranded in the middle of renovations or other projects. Instead of allowing people to borrow 100% or more of the value of their homes, some lenders were balking if the value of the primary mortgage plus a line of credit equaled more than 60% of the home’s (perhaps rapidly falling) price.

As home prices have bottomed in many areas and started rising in others, the trend now seems to be reversing somewhat. One in five lenders reported in mid-2012 that they had eased their lending standards for home equity borrowing, according to a report published by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. That was a huge change from three years earlier, when the vast majority of lenders were still tightening their standards and none were easing.

You still can’t borrow 100% of your equity, but borrowing 80% or even 90% might be possible with good credit and a solid employment history. And there are reasons you might want to do so.

Before we get into good and bad uses of home equity, though, let’s review some of the basics.

Home Equity Loans Versus Lines of Credit

With both types of home equity borrowing, you’re pledging your house as collateral. Both also offer potentially tax-deductible interest (up to a loan amount of $100,000).

You need to be able to itemize to deduct the interest, and you could lose this deduction if you’re subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax, a nasty parallel tax system. (Under the AMT, only home equity borrowing that’s used to fund home improvements is considered deductible.)

Here’s how home equity loans and lines of credit vary:

Home equity loans are installment loans, like regular mortgages and auto loans. You typically receive your loan proceeds all at once and are expected to pay back the money over five to 15 years (although sometimes the loan term is longer).

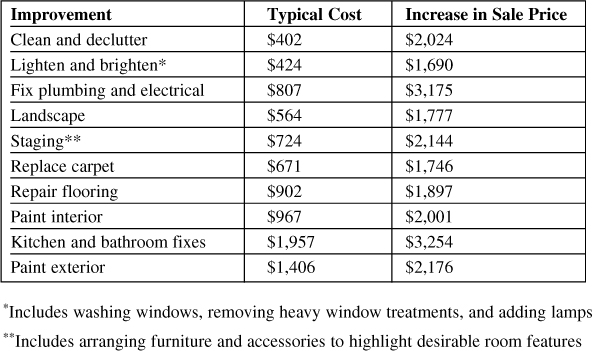

Your payments typically are fixed, as is your interest rate. The rates on home equity loans are usually about 2 to 3 percentage points higher than on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage, but they vary according to your credit score (see Table 5.1). People with mediocre scores can pay rates that are 6 or 7 percentage points higher than a typical mortgage, if they can talk anyone into giving them a loan.

Table 5.1. Home Equity Loan Rates by Credit Score for a 15-Year Fixed-Rate $50,000 Home Equity Loan

Source: MyFico.com and Informa Research

A home equity loan is usually the right choice when you pretty much know the cost of your purchase or project and you need several years to pay it off. A major home-improvement project that adds significant value to your home, for example, might be a good candidate for a home equity loan.

You also might consider a loan when you want to lock in a low interest rate in a rising-rate environment.

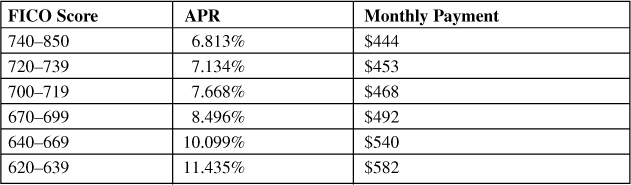

Home equity lines of credit are more like credit cards. You have a credit limit that you can borrow against, and paying down your debt frees up more credit that you can spend if you want. Home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) have variable interest rates that are typically tied to the prime rate. If your credit score is excellent—760 or above—and your total borrowing against your home doesn’t exceed 60% of its value, you could qualify for a rate that’s a bit below the prime. People with less-sterling scores can pay several points above prime. See Table 5.2.

Table 5.2. Home Equity Lines of Credit Rates by Credit Score for a $50,000 Adjustable-Rate Line

Source: MyFico.com and Informa Research

A line of credit is often better for shorter-term borrowing, or when you may need to tap your equity for different amounts over time.

HELOCs differ from credit cards in that they’re typically not open ended. HELOCs usually allow you to borrow against your limit for the first 10 years or so and pay only the interest charges. After that, however, the “draw” period ends, and you’re required to start paying principal and interest to pay off your debt.

You may be able to extend your draw period with some lenders or refinance to a new home equity line of credit that offers a new draw period.

The way most homeowners pay off their home equity debts, however, is when they sell their homes. The balance of what they owe is deducted from their sale proceeds. This can make home equity borrowing seem almost painless because you’re not writing check after check to retire the debt.

But remember, if you hadn’t borrowed with a home equity loan or line of credit, you’d have that much more money to use to buy your next home or pay for whatever other long-term goal is most important to you.

For example, the wealth you build up in your home can help you afford a comfortable retirement. Many people near retirement discover they haven’t saved enough to quit work, or their investments haven’t performed as well as they hoped. But if these folks have substantial home equity, they can sell their houses, downsize to smaller places, and have piles of cash to live on.

Other people use their home equity to fund college educations or to add rooms as their families expand. Again, the money to pay for these dreams won’t be available if it’s already been spent on less important things along the way.

Questions to Ask Before You Borrow

Any time you’re tempted to use your home equity, ask yourself how important the purchase is. Will it help you achieve one of the most significant goals in your life? Homes are most people’s major source of wealth, and that wealth shouldn’t be frittered away on anything that’s not close to their hearts.

You also should think twice about spending home equity on anything that doesn’t gain in value. Your equity, if left alone, will rise over time. You don’t want to blow it on a bunch of purchases that will soon have little or no value.

That said, let’s deal with some of the most common ways people spend their home equity.

Paying off credit card debt. It’s so tempting to pay off high-rate, nondeductible credit card debt with low-rate, potentially deductible home debt. But the unwary face all kinds of traps.

One of the biggest is that you’ll just end up running up more debt because you haven’t corrected the problem that led you to overspend in the first place.

Credit card debt is short-term debt, which generally should be paid off using your current income. Transferring it to a home equity loan or line of credit can turn it into long-term debt. If you don’t pay it off quickly, you could actually wind up paying more in interest than if you’d buckled down and paid off the cards.

You’re also replacing unsecured debt, which could be wiped out in bankruptcy court, with debt that’s secured by your home. If your overspending leads you to go broke, you may well regret nailing yourself to this debt.

If you do decide to use home equity to pay off credit cards, make it a onetime event. Cut up your credit cards and learn to live on cash until you’re sure you can live within your means.

Paying for vacations, weddings, and big-screen TVs. This kind of misspending is a nonstarter. Luxuries should be paid for with cash, not credit, and certainly not using your most important asset. If you can’t afford it without touching your equity, you can’t afford it.

If you’ve already succumbed, make a pact with yourself to pay off the debt as quickly as possible.

Buying stocks, real estate, or other investments. I know one woman who used the equity in her first home, a duplex, to purchase an apartment building and then leveraged the equity in that to buy a single-family home. She did all this in the pricey San Francisco area, on a very modest salary. She took a calculated risk, and it paid off handsomely.

I’ve heard from many other folks, however, who pillaged their home equity to buy investment properties in Arizona and Nevada that are now worth a fraction of what they paid.

Leverage can work for or against you. That stock you’re sure will skyrocket could become worthless tomorrow; that apartment building might be taken over by a violent gang, or simply sit with too many vacant units. If the value of what you’re buying could drop to zero—which is true of any stock and many other investments, although it’s rarely true of real estate—don’t use your home equity to buy it. In any case, before you pull out equity to invest, understand the risks you’re taking and try to keep at least a 20% cushion of equity in your home in case things go wrong.

Buying cars. Cars and other vehicles lose value pretty fast, which doesn’t make them particularly good candidates for your home equity. On the other hand, if you have to borrow to buy a vehicle anyway, you may be able to get a lower and potentially tax-deductible rate if you use your home, rather than the car, to secure the debt.

What you don’t want to do is let this debt ride for a decade or more, paying only the minimum required. In general, the life of any loan shouldn’t exceed the life of whatever you buy with the money, and that’s particularly true here. A much better course is to pay back the loan within three or four years. That will free up your equity to be reused for other, better purposes and keep you from overspending on your vehicle.

Education. Now you’re getting warmer. Getting your kid through State U. isn’t a traditional investment in that it probably won’t increase your personal net worth. But it’s an investment in her future that should pay off abundantly during her lifetime. Most studies show that college educations pay for themselves by the time the graduate is in her early 30s, even when you take into account the income she missed by not working full-time during her college years.

Not every parent feels an obligation to help with college, of course, and kids can always get their own student loans. If you do want to help, you should also investigate parent PLUS loans, which allow you to borrow for a child’s education without using your home as collateral. (You can find more information at the U.S. Department of Education’s financial aid Web site, http://studentaid.ed.gov.) You should know that student loans can’t be discharged in bankruptcy court, however, and in any case you shouldn’t borrow more than you can comfortably pay off before retirement while still being able to save for retirement.

If you opt for a home equity loan or line of credit, it’s just as important to keep your borrowing reasonable. Don’t let your total mortgage debt exceed 80% of the value of your home, and make sure you can afford the monthly payments. You don’t want to wind up losing your house and having to move into your kid’s dorm room. If you can’t get the extra debt and your primary mortgage paid off by retirement, you probably can’t afford this additional loan. You also shouldn’t tap your home equity if you’re behind on your retirement savings because you may need it to fund your old age.

Emergency funds. Plenty of financial planners recommend that their clients set up home equity lines of credit to tap in case of emergency. This is seen as a supplement to any cash savings their clients have accumulated.

Given how little savings most families have, this is probably a smart idea—if you have the discipline to leave the line of credit alone. Every dollar you spend on something frivolous is a dollar you won’t have when you need it.

If you decide to go forward, this is definitely something you’ll want to have in place before you lose your job. You might still be able to get the line of credit afterward, but you’re likely to pay a higher rate for the privilege.

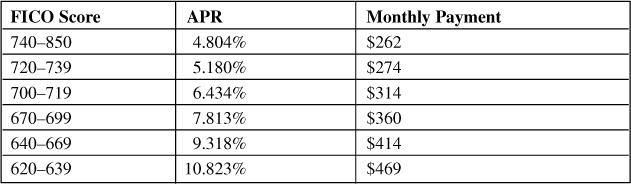

Home improvements and repairs. You may think this is a slam dunk. Doesn’t fixing up your home add value? Isn’t that the kind of appreciating asset that home equity is supposed to fund?

There are a few flaws in that thinking. The first is that repairs don’t really add value; they just keep your home’s value from sinking. The next buyer will expect that you kept your home in good shape. If you didn’t, the repairs the buyer has to make usually are deducted from the offering price.

The best way to pay for repairs is with cash. Personal finance guru Eric Tyson recommends putting aside 1% of your home’s value each year to pay for repairs. Some years you won’t use all the money, but you’ll make up for that in the years when you need a big fix, like a new roof or heating system.

If the furnace conks out before you can put the cash together, a home equity loan or line of credit may be your next-best recourse.

Now to home improvements. These usually add less value than you think, and that value tends to wane, not grow, over time (see the sidebar near the end of this chapter titled “The Truth About Remodeling”).

People also can delude themselves that they “need” to remodel. Home improvements are a “want,” not a “need,” that should be balanced with all your other discretionary spending. A remodeling project certainly shouldn’t replace or infringe on the money you need to be putting aside for retirement or other long-term goals.

If you decide to use your equity to pay for a remodel, remember that the money you’re spending isn’t really cheap—it’s your long-term wealth.

Also you should know that although home equity loans and lines of credit are probably the most popular way to pay for home remodels, they’re not the only options. You might also consider the following:

• Cash-out refinancing. You basically get a new, larger mortgage to replace your existing home loan and get extra cash to pay for improvements and repairs. This could be a good choice if

• Interest rates have dropped since you got your current mortgage.

• You have a ton of equity.

• You’ll be in the home long enough to recoup your refinancing costs.

• Your project adds lasting value to your home.

• Title 1 loans. If you don’t have enough equity in your property to fund needed improvements or repairs, you may be able to borrow up to $25,000 through the Federal Housing Administration’s Title 1 program. The loans are offered through banks and other lenders, and the interest rates are negotiable. Your interest payments, though, typically aren’t deductible, and the loan can’t be used for luxuries, like adding swimming pools.

• Construction loans. If you’re looking at a major remodel, and you don’t have enough equity to pay for it, consider a construction loan if you can find a willing lender. They’re typically offered by regional banks and mortgage companies.

Construction loans are short-term, interest-only loans that are designed to be replaced by a regular mortgage once your remodel is finished. Lenders may base the amount you get on your projected costs of construction, the future value of your home, or both.

These loans differ from mortgages and home equity borrowing in that you don’t get the money all at once. Lenders typically dole out your funds in five to 10 “draws” timed to various stages of construction.

Construction loans come in two types:

• The all-in-one loan (also called the rollover or construction-to-permanent loan) becomes a standard mortgage after construction is completed. The borrower pays only one set of fees, and there’s only one closing, which reduces the hassles.

• The construction-only loan must be paid off or replaced by a conventional mortgage once construction is completed. That means more fees and hassles, but borrowers may be able to get better rates on the replacement mortgage.

In either case, interest rates on construction loans are usually fixed for the life of the loan, which is typically a year or less. If you have good credit, you may be able to swing a rate as low as prime, although most people have to pay an additional percentage point or two.

That may seem like an extremely low rate, given how risky construction projects can be. But the lender gets its pound of flesh. You’ll also pay fees—lots of them, to cover everything from origination costs to the lender’s inspections of the project’s progress. It’s not unusual for the lender’s fees to total 10% to 15% of the construction’s cost.

You’ll probably want to shop around to get the best deal, getting quotes from at least three different banks and mortgage lenders that specialize in construction loans.

Summary

Your home equity is one of your greatest sources of long-term wealth. You don’t want to treat it lightly or blow it on short-term spending.

Credit Limits

• In general, you shouldn’t use your home equity to buy anything that declines in value.

• If you decide to tap your home’s equity, try to keep your total borrowing (your mortgage plus any home equity loans or lines of credit) to 80% of your home’s value. That will help you get good rates and terms, as well as preserve an important financial cushion for emergencies.

• Make sure you can make more than minimum payments on any home equity loans or lines of credit. If you can’t manage that, you can’t afford whatever you’re using the home equity to buy.

• Consider borrowing only half of the cost of any remodeling project and pay for the rest in cash.

Shopping Tips

• The rate you get on home equity borrowing depends heavily on your credit score. Check out the Loan Savings Calculator at MyFico.com to see what kinds of rates you should expect, given your score.

• Contact several different lenders to shop for the best rates and terms.