2. Your Debt Management Plan

The previous chapter showed you how most advice on debt is too simplistic. People are often encouraged to pay off the wrong debts, in the wrong order, and at the expense of other, more-important financial goals.

That advice can lead people to do some pretty financially disastrous things, like prepaying mortgages instead of contributing to their 401(k)s or stranding themselves without enough financial flexibility to survive a job loss or other setback.

A better approach is to figure out which debts are contributing to your wealth and flexibility and which aren’t. Pay off the ones that are endangering your financial well-being and better manage the ones that are increasing your net worth.

But how, exactly, do you do that?

The answer is a three-step plan that helps you understand where you are now, where you want to be, and how best to get there:

• Get intimate with your debt. You need to know more than how much you originally borrowed and the monthly payment (which, unfortunately, is all many people remember about what they owe). You need to know your balances on every account, what interest rates you’re paying, whether that interest is deductible, when and how the rates can change, and whether you’ll face any kind of penalties for paying off an account early.

You also need some benchmarks, such as what interest rates you should be paying and the maximum amount you should carry for each type of debt. You can find that information, along with a detailed discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of different kinds of debt, in the following chapters.

• Assess your overall financial situation. You can’t make smart debt management decisions in a vacuum. Your other financial goals, like retirement or college savings, can have a profound impact on which debts you pay off and how quickly. You also need to make sure you have enough of a financial cushion to get you through the bad times that can strike any family.

The discussion in this chapter gets you thinking about how to prioritize your financial goals, including repaying your debts. As you explore the chapters dealing with each kind of debt, you may refine your plan further.

• Create your game plan. Once again, no one debt repayment strategy works for everyone. You need to evaluate your debts, goals, and finances to devise a plan that’s smart and workable. The end result probably will look different from the program that would work for your neighbor, your friend, or your brother-in-law. The point is to customize your debt management plan so that it makes the most sense for you and your family. In Chapter 11, “Putting Your Debt Management Plan into Action,” you create a detailed program that incorporates all your goals. Chapter 11 also has tips for finding the cash to get you to the finish line as quickly as possible.

Okay, let’s take these steps one at a time.

Get Intimate with Your Debt

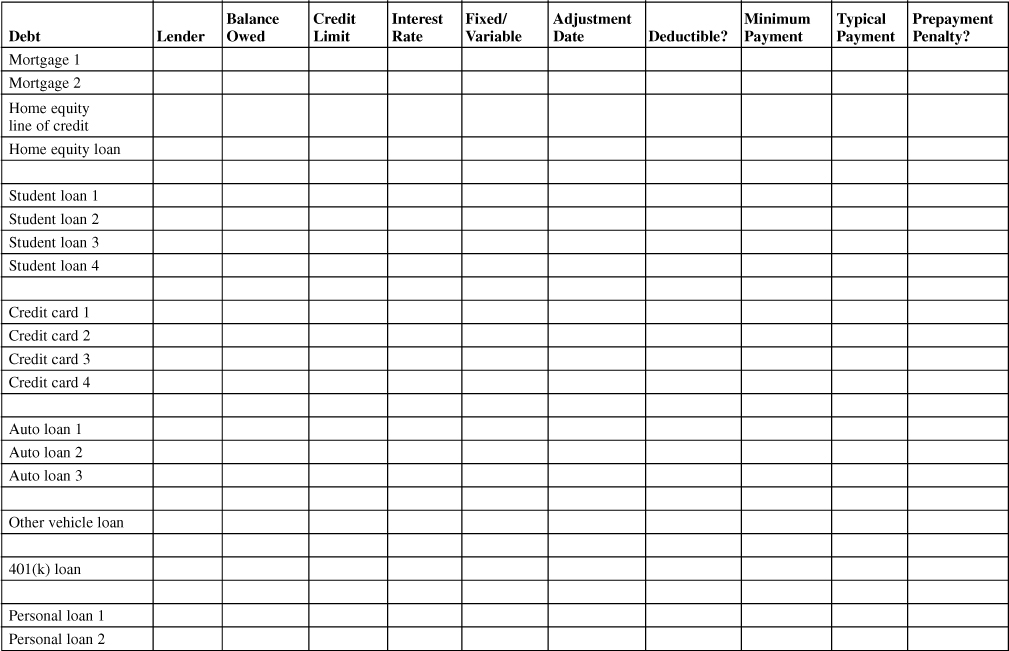

You can get started right now with the first part of this step: knowing exactly what you owe. Dig out your credit card statements and loan paperwork so that you can list all your debts with the relevant details. You can use the form provided in Table 2.1 or a blank sheet of paper. If you’re into such things, you can even create your own spreadsheet.

Table 2.1. Debt Repayment Worksheet

Make sure you include every debt you owe, including the following:

• Mortgages

• Home equity loans and lines of credit

• Credit cards

• Student loans

• Auto loans

• Other bank or credit union loans

• Money owed to check-cashing outfits or payday lenders

• 401(k) or other retirement plan loans

• Debts owed to friends and family

For each debt, write down the following:

• Current balance owed. At this point, it really doesn’t matter what the original loan amount was; what matters is how far you have to go.

• Whether the loan is an installment or revolving debt. Installment debts include mortgages, auto loans, and other debt where you have a set schedule of payments to make and a specific payoff date when the loan is expected to be retired. Revolving debt includes credit cards and lines of credit, where you have a credit limit that you can draw on—and pay off—repeatedly. Paying off revolving debt generally increases your financial flexibility because you can always draw on that freed-up credit line in an emergency. That may not be possible with an installment loan.

• Current interest rate. You should find this on your most recent statements, typically listed as your “annual percentage rate.”

• Whether the rate is fixed or variable, and when it might change next. Credit card rates typically are variable and can change from month to month. Installment loans usually carry fixed rates, unless you took out an adjustable-rate mortgage. If you’re not sure when the rate is scheduled to change, ask your lender.

• Whether the interest is tax deductible. This is actually more complicated than it might seem, but we get to that in a minute.

• Minimum payment owed. Again, this is something you can probably find on your latest statement.

• Typical payment made. Ditto.

• Whether there’s a penalty for paying off the loan faster than scheduled. Prepayment penalties aren’t that common. You’ll find them on some mortgages and auto loans, but not all. If you’re not sure, call and ask.

You can add one more step if you really like to play with numbers by trying to figure out your “after-tax” rate on your tax-deductible debts. Essentially, you need to subtract your tax bracket from the number 1 and multiply the result by the interest rate you’re paying.

For example, if you’re in the 25% bracket, you’d subtract .25 from 1 to get .75. Multiply that by a 6% interest rate (.06), and your after-tax rate would be 4.5%.

Some folks like to get even more precise and factor in their state and local tax rates as well. Someone in the 25% federal bracket who lives in California may pay an 8% state income tax rate. To figure the effective rate, you multiply the federal rate by the state rate and then subtract the result from the combination of the two rates. This reflects the fact that you can deduct your state taxes from your federal return. It works like this: .25 times .08 equals .02. Add .25 and .08, and you get .33. Subtract .02 from that, and you get .31, so 31% is the combined effective tax rate.

If you enjoy this kind of thing, have at it. But remember that these are still just estimates of what your rate will be over time. Tax rates change constantly, so your tax benefit may be more or less than you think, depending on what’s on your tax return in any given year.

Which Debts Are Deductible?

The issue of tax deductibility confounds a lot of people, who assume a loan is either tax deductible or not. The reality, like so many things in personal finance, can be far more complicated.

Mortgage interest may be tax deductible—or it may not. Technically, you can write off the interest you pay on mortgages of $1 million or less, as long as you owe the money on your primary residence or a second home. But if you don’t itemize your deductions—and two thirds of the nation’s taxpayers don’t—you don’t get any tax benefit from your mortgage.

About half the nation’s homeowners get absolutely no tax benefit from their homes—either because they own their homes free and clear or because they’re paying too little in mortgage interest and other potentially deductible expenses to justify itemizing. You had to have deductions worth more than $11,900 for itemizing to make sense in 2012 if you were married filing jointly, or $5,950 if you were filing single.

If you’re not sure whether you itemize, check last year’s return. If you just bought a house this year, you can use TurboTax or another tax program to see if you’ll get a tax benefit from your mortgage, or you can talk to a tax pro.

Even if you do itemize, you may be getting only a partial benefit from your mortgage. If your interest payments, property taxes, and other deductible expenses total just $12,000 and you’re married, you get an additional tax benefit of just $100. If you’re in the 25% bracket, that means all your deductions really saved you only about $25. That’s very little tax bang for all the bucks you paid in interest.

Home equity interest also is potentially deductible. If you itemize, you typically can write off interest on home equity lines of credit or home equity loans, as long as the amount owed is less than $100,000. If you owe more, you can’t deduct the interest on the part of loan that exceeds that limit.

Your ability to write off your home equity interest can be limited even more if you fall under Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) rules. This Byzantine system was originally designed to make sure the wealthy didn’t exploit loopholes to escape paying taxes, but today it’s snagging many farless affluent families who simply have lots of deductions—usually because they have a lot of kids, they live in high-tax states, or they have certain kinds of stock options from their employers.

AMT rules severely restrict the deductions you’re allowed to take, including home equity interest deductions. If you borrowed the money for anything but home improvements—if you paid off credit card debt or bought a car with the money, for example—you can’t deduct the interest.

You probably know if you’ve been hit by AMT rules, but if you’re not sure, talk to a tax pro.

Student loan interest probably is deductible. Congress loosened the rules so that married couples with incomes of under $155,000 and singles with incomes of under $75,000 can deduct at least some of their student loan costs (up to a limit of $2,500 a year). (All these figures were accurate as this book went to press, but check with your tax pro, a tax guide, or www.irs.gov for updates.) There’s no longer a requirement that the loans be within the first 60 months of repayment. Also you don’t have to itemize to take advantage of this deduction—a real plus.

Interest on credit cards and most other debt typically isn’t deductible. If you own a business and carry a balance on your business credit card, you typically can write off the interest. People who are self-employed also might be able to deduct some of the interest paid on auto loans for cars used in their businesses.

Otherwise, credit cards, personal loans, auto loans, and other types of consumer debt don’t merit a deduction.

You also need to consider one more issue, as discussed next.

Am I Paying the Right Rate?

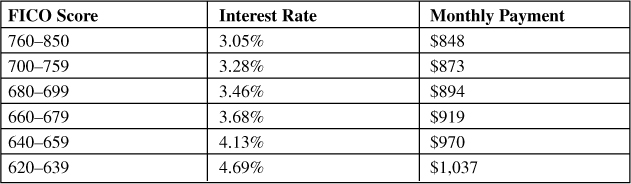

Most lending these days is based in part on your credit scores, the three-digit numbers that lenders use to help gauge your creditworthiness. Credit scores are a snapshot of your credit picture that tells mortgage lenders, auto finance companies, credit card issuers, and other financial institutions how likely you are to default on your payments. The most-used score is known as the FICO, after its creator, Fair Isaac Corp.

Good scores will land you the best rates and terms; mediocre or poor scores can cost you tens of thousands of dollars more in interest over your lifetime.

Table 2.2 shows how much difference even a few points can make on a 30-year, $200,000 mortgage.

Table 2.2. Mortgage Rates by Credit Score

Source: MyFico.com and Informa Research Services

The use of credit information has even seeped into areas of your life beyond lending. Insurers use a form of credit scoring to determine premiums, and landlords use scores to determine who gets an apartment and who gets denied. Even employers can make judgments about whom to hire, fire, and promote based on personal credit information.

So much rests on your credit scores that you really need to know what yours are and how to improve them.

You may have heard that U.S. residents are entitled to one free credit report a year from each of the three major credit bureaus. (You can order your reports at AnnualCreditReport.com or by calling 877-322-8228.) But those reports don’t include a free look at your FICO credit scores. For that, you usually have to pay.

The one place you can buy FICO scores is from MyFico.com. They cost about $20 each. Other sites, including those run by the credit bureaus, sell or give away credit scores, but those scores typically aren’t the FICO scores most lenders use.

Contrary to what you may have heard, checking your own credit reports and scores won’t hurt your credit. In fact, it’s something you need to do to make sure your reports are accurate and that you’re getting the best possible rates and terms.

The following chapters show you what people with credit scores similar to yours actually pay in interest on their loans. Because rates can vary widely over time, you might also want to visit the MyFico.com site and use its Loan Savings Calculator, located in the Credit Education section, to get more up-to-date results for mortgages and home equity lending. Bankrate.com is another good source of information on prevailing loan rates.

If your scores are below 720 or so, you need to focus on getting them higher. I wrote a whole book about how credit scoring works and how best to boost your scores—Your Credit Score: How to Improve the 3-Digit Number That Shapes Your Financial Future (2011, FT Press). Here’s the thumbnail version of the best ways to get your numbers up:

• Fix any serious errors in your credit report, such as accounts that aren’t yours or negative information that’s more than seven years old (or 10 years old in the case of bankruptcy).

• Pay your bills on time, all the time. Even a single late payment can devastate your score.

• Pay down your debt. The FICO formula likes to see a wide gap between your credit limits and the amount of credit you actually use, particularly on revolving accounts such as credit cards.

• Apply for credit sparingly.

Exhausted yet? Well, get another cup of coffee because we’ve just begun.

Assess Your Financial Situation

Every financial plan needs to start with goals: what you really want and are trying to achieve. You may have very specific notions: a trip to Europe in two years, college education for your kids in 10, retirement in 25. Or you may be looking for a state of mind, such as feeling in control, content, and not anxious about money.

The real work of financial planning comes when you try to figure out which goals are most important, how to prioritize them, and how to save for them while paying the expenses of your day-to-day life.

Setting you up with a full-fledged financial plan is well beyond the scope of this book. But you must address two goals before you construct any debt repayment plan—retirement savings and financial flexibility.

Retirement Savings

This needs to be a high priority for almost everybody. It should take precedence over just about every other goal—including your child’s college fund.

This is really tough for many parents to hear because they’re so focused on providing a better life for their kids. One of my personal finance professors put it this way: If worse comes to worst, your kid can always borrow money for school. No one will lend you money for retirement.

In the past couple of decades, the burden of ensuring an adequate retirement has shifted from the employer to the worker. Instead of traditional defined benefit pensions, which promise a set paycheck in retirement to loyal employees, companies increasingly offer defined contribution plans like 401(k)s. How much money workers will have to spend in retirement depends on how much they contribute and how well they invest the money. The company makes no promises.

Another change is in the works. Most retirees today get half or more of their incomes from Social Security. But Social Security has already promised far more benefits than it can deliver to future generations. Higher taxes or cuts in benefits may be needed. If the system is ever privatized, more risk will be shifted to workers.

Finally, we’re living longer than ever before—and that means living longer in retirement. Many Americans plan to cope with the high costs of retirement by working longer. The average retirement age for men has risen from 62 to 64 since the mid-1990s, and from 60 to 62 for women, according to a new Center for Retirement Research at Boston College analysis of Census Bureau data. More than one third of the workers surveyed by the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) expected to retire after age 65. But, as the EBRI noted, nearly half of current retirees it surveyed said they left work earlier than they’d planned—often due to ill health, disability, or layoffs.

All these issues underscore the need for most of us to stockpile a decent amount of money—and the earlier we start, the better.

The value of time in helping our savings grow really can’t be overstated. Even relatively small delays in getting started, or brief interruptions along the way, can have an outsized impact on how much we can put away.

The Value of Starting Early—and Not Stopping

To illustrate this point, many financial planners use the example of the twins. One twin puts $3,000 aside in a Roth IRA starting at age 22. She continues contributing $3,000 annually until age 32, and then she stops—never to contribute another dime.

Her sibling, in contrast, doesn’t start contributing until age 32 but continues until they both retire at 62.

Who has more money? The answer may surprise you: the first twin. She contributed far less ($30,000 total) than her sister ($90,000), yet she accumulates $437,320, compared with her sister’s $339,850 (assuming that both siblings earn an average 8% annual return). The first twin’s early contributions gave her a head start that her sibling couldn’t match.

This illustration shows why it’s important to get an early start; now here’s one to show why it’s important to keep going.

Let’s say our siblings each put $10,000 into a 401(k) annually starting at age 22. Ten years later, the second sibling stops contributions for five years to pay off some debt; the first sibling continues funding her 401(k).

Once she restarted her contributions, how much would Sibling Two have to shell out annually to catch up with her sister by retirement age? The answer: $15,496 a year, or 55% more each year than she would have had to contribute if she hadn’t stopped. She’ll need to make those extra payments for 25 years to match her sister’s kitty at age 62.

There’s another reason not to stop. Many people who suspend retirement contributions have a tough time resuming their savings later, just as those who put off getting started often let inertia keep them on the investing sidelines. We can always find other ways to spend our money once we’ve got our hands on it; that’s why most of us are far better off simply putting our retirement contributions on automatic and not stopping, whatever the short-term temptations.

That doesn’t mean we should tolerate high-rate debt in our lives or delay paying it off indefinitely. The better solution is typically to find money for debt repayment by cutting other spending, not by shortchanging our retirement savings.

Financial Flexibility

Retirement isn’t the only factor you need to consider as you construct your debt repayment plan. You also need to make sure your household can survive the financial catastrophes that can wait around almost any bend.

As mentioned in the previous chapter, we Americans are pretty lousy at saving for a rainy day. Fewer than one out of three households have the cash on hand to survive even a short stretch of unemployment, and many live paycheck to paycheck. This helps explain the soaring bankruptcy rate and the state of financial stress in which many people live.

Unfortunately, traditional debt repayment plans ignore how close to the edge most people live. They typically advise paying off the highest-rate debt first, even if doing so could make you more vulnerable to financial setbacks.

A few fortunate folks don’t have to worry about their financial flexibility quotient—they’ve got plenty of cash to tap in an emergency. If you can answer “true” to any of the following three statements, you’re one of the lucky few who don’t need to make financial flexibility an immediate goal:

• You have at least one year’s worth of expenses saved in a safe, liquid, and easily accessible place like a money market or savings account.

• You have less than one year’s worth of expenses saved in cash, but you have ready access to a similar amount of credit via cards or a home equity line of credit.

• You have friends or family who are well-off and who would gladly lend you enough money to pay the bills for six months.

(Personally, I wouldn’t advise anyone to rely on the kindness of others to survive a job loss or other financial setback—especially if your borrowing would cause your lender financial hardship. But if you have the proverbial rich aunt or doting parent who would step in if necessary, you already have more financial flexibility than most people.)

As noted in the previous chapter, most people can’t answer yes to any of these questions. But you still might not need to make emergency savings a high priority if you can answer “true” to all three of the following statements:

• Your household has more than one income earner.

• You work in a growing industry where the possibility of layoffs is remote.

• You have adequate life, health, and long-term disability insurance and enough cash to continue your coverage for at least six months if one or both income earners lose their jobs.

If all three are true, you should still boost your emergency savings eventually, but it needn’t be one of your highest priorities.

Save or Pay Off Debt First?

Again, most people aren’t in the enviable position of having financial flexibility to spare. And what many want to know is: Should I hold off on my debt repayment plans until I get my emergency fund pulled together, or should I pay off my debts first?

The question of whether to save or repay is one that people with a little financial savvy love to debate. The save-firsters point out that the more cash on hand you have, the better you can survive an emergency without running up more debt.

The problem with that approach is that many people would be paying pretty high rates on their debt while they slowly put together their cash stash. It can take a typical family a couple of years, or more, to accumulate even three months’ worth of emergency cash. That’s a long time to pay double-digit rates on your debt.

I’m of the school that urges people to pay off their credit card debts before they concentrate on the emergency fund. It makes sense to put aside a small amount of money—$500 or so—to cover small setbacks so you don’t have to add them to your debt. But after that, you should focus on clearing your cards.

Credit cards usually carry pretty high rates, and every dollar of credit card debt you pay off typically frees up a dollar of unused credit space on your cards that you can use if you face a real emergency. Unused credit on cards and a home equity line of credit can serve as a de facto emergency fund until you get around to saving for a real one.

The key, of course, is to stop using your cards while you’re in debt repayment mode unless you’re facing a real emergency. You can’t crawl out of the hole you’re in if you keep digging.

Paying down revolving debt like credit cards and lines of credit can have another beneficial effect: It can quickly boost your credit score. Remember, the credit-scoring formula measures the gap between the credit you’re using and your available limits; the wider you can make that gap, the better. Paying down debt is a great way to strengthen your scores.

Case Studies

By now, you’re beginning to grasp how complex figuring out the right debt repayment plan can be. We use two fictional characters, Stefano and Ingrid, as examples to explore further the necessary trade-offs people need to make when figuring out their plans of attack.

Stefano and Ingrid have many financial details in common: They both have a mortgage, a student loan, an auto loan, and credit card debt. Both have a child they want to send to college, and both are somewhat behind in saving for retirement, although they’re contributing enough to their workplace 401(k)s to get the full company match. Yet their situations—and debt repayment plans—are quite different.

Stefano is married; he and his wife both work outside the home. They both feel reasonably secure in their jobs and have considerable equity in their home that they could tap in an emergency.

Stefano’s student loan rate is relatively high at 6.8%. His auto and credit card rates are low at 5% each, however, thanks to his excellent credit score.

Ingrid’s credit, by contrast, is pretty mediocre, thanks to the devastating effects of her divorce. The single mother drained most of the equity in her home to pay off the debts from her marriage, and she has almost nothing in savings. Her auto and credit card rates are in the double digits, thanks to her middling credit scores. The good news is that her student loan rate is low because she qualified for subsidized rates of 3.8%.

Ingrid has poor financial flexibility because her household has only one income, little savings, and no home equity. Her plan is as follows:

1. Save one week’s salary (that’s gross, or before taxes and deductions, not after) in a savings account. This fund should help her meet unexpected expenses so that she can stop using her plastic while she pays off her credit card debt.

2. Pay off the cards, starting with the highest-rate card first.

3. Once that debt has been paid down and her credit score has improved, refinance the auto loan to a lower rate.

4. Boost retirement savings until she’s on track for retirement.

5. Start building emergency savings.

Paying off the car and student loans isn’t a priority because the repayments wouldn’t enhance her financial flexibility. She couldn’t, in effect, get the money “back” that she paid into these debts. That’s a sharp contrast to payments on a revolving debt like credit cards; usually, every dollar you pay down is a dollar that you can borrow again in an emergency.

(Okay, technically she could get another loan against her car, but the amount would be reduced from her current balance because the value of her car would have dropped considerably by the time she got it paid off.)

You’ll notice something else isn’t a priority: her child’s college fund. Until her own retirement and emergency savings needs are met, she shouldn’t be investing money for someone else.

Of course, once she’s on track with savings and retirement, she may very well decide to put aside some money for college—or she might choose to retire the auto loan and start saving for her next car. What she probably won’t accelerate are payments on her student loan, which is a cheap and flexible debt to have.

Now let’s look at Stefano’s plan. Although he’s in a much more secure financial situation, he too must juggle multiple priorities. His student loan is his highest-rate debt. His credit card rate is fixed at 4.99% for the next few months, but it likely will rise after that. Meanwhile, he needs to have at least some money on hand so that he’s not in the position of charging auto repairs or other predictable expenses to either his credit cards or his home equity line of credit.

Stefano’s first step is like Ingrid’s: Put aside some cash. After that, it’s quite different:

1. Save one week’s salary (that’s gross, or before taxes and deductions, not after) as cash for emergency expenses.

2. Boost retirement savings by funding a Roth IRA.

3. Pay off the credit cards.

4. Raise retirement contributions until he’s on track for retirement.

5. Simultaneously begin increasing emergency savings while paying down the student loans.

6. Begin contributions to his child’s college fund.

Some would be appalled at the idea of increasing retirement contributions when credit card debt is outstanding. But funding a Roth is a use-it-or-lose-it proposition, and Stefano’s good credit score means that he’ll most likely be able to find another relatively low rate even if his current card goes up.

Still, Stefano knows it isn’t wise to have credit card debt indefinitely, even at single-digit rates. The balance on his cards is money he can’t access in an emergency, and it leaves him vulnerable to all the various tricks credit card companies like to pull on their customers (for more on these shenanigans, see the next chapter).

Stefano’s student loan, by contrast, is a relatively benign debt. The interest is tax deductible, reducing its real cost, and Stefano can temporarily suspend or reduce his payments if he loses his job.

The student loan debt also is big enough that it will take years to retire, even if Stefano devoted all his available cash to paying it off. Stefano doesn’t want to wait that long to have a three-month supply of cash on hand, which is why he wants to start pursuing both goals at the same time.

Stefano also has no plans to retire his auto debt. He figures his college fund contributions will earn greater returns than what he’s paying for the loan.

The choices Stefano and Ingrid made may be right for them and wrong for someone else. People have to weigh their goals, understand their situation, and choose a path that makes sense to them.

Create Your Game Plan

By now you have at least a rough idea of how you want to prioritize your goals, including which debts you’ll pay off first. To complete your game plan, two more steps remain: locating the cash to fund your plan and making sure you’re paying the lowest rates possible so that you can get to the finish line faster.

Chapter 11 goes into more detail about the various places you can find cash. But here’s a list to get you thinking:

• What could you sell? Unloading an unneeded vehicle could raise some significant cash (and lower your auto insurance premium as well). Or maybe you could auction that Hummel collection on eBay. Perhaps you could hold a yard sale to simultaneously reduce your clutter and boost your bank balance.

• Where can you cut? Almost every budget has some fat. Many families spend a big chunk of their disposable income on groceries and dining out, two areas that are very easy to trim. Gym memberships can be a big waste of cash. Or you can cut back to basic cable, or drop the service altogether. Remember, the deeper you slice, the quicker you’ll be out of debt. If you need more ideas, check out one of the many frugality-oriented Web sites like The Dollar Stretcher (www.stretcher.com) or a book like Amy Dacyczyn’s The Tightwad Gazette.

• Can you pick up more income? Maybe you’re overdue for a raise at work or can temporarily add a second job. Now is probably not the time to launch a risky, cash-eating side business, but some people can turn their hobbies into moneymakers (by selling handiwork, for example) or start low-cost service businesses walking dogs, running errands, or house-sitting.

Getting your interest rates down will save you money as well. The following chapters have specific information about the best ways to reduce your rates on the major categories of debt, such as credit cards, mortgages, auto loans, and student loans.

Should You Pay Off Your Debt with More Debt?

You may be tempted to implement a more sweeping solution by using a home equity loan, a cash-out mortgage refinance, or a debt consolidator or by borrowing from a workplace retirement plan to lower your rates or your payments.

In some situations, these loans make sense. All too often, though, these solutions make matters worse.

For one thing, these loans usually turn what should be short-term debt into long-term debt. You could end up paying more in interest than if you had just paid off the cards out of your current income.

If you haven’t addressed the basic problem that got you into troublesome debt, you could just be digging the hole deeper. Most people who use home equity lending to pay off credit cards, for example, run up new credit card debt within a few years. The wealth they should be building with their homes is instead being drained away forever.

Using home equity lending or a cash-out refinance has another problem. Normally, credit cards, medical bills, and personal loans can be erased in a bankruptcy filing if your financial situation really goes south. Pay them off with mortgage debt, though, and you’ve just secured them with a loan that typically can’t be wiped out.

The same is true of retirement plan loans. Most 401(k)s, 403(b)s, and other workplace plans are protected from creditors’ claims in bankruptcy court if you should have to file.

Withdrawing money from a 401(k) has another downside: You lose out on the tax-deferred returns that your money could earn in the plan if you left it alone. Every $10,000 you take out of a 401(k), for example, could cost you $100,000 or more in future retirement income, assuming it had been left alone to grow at an 8% average annual rate for 30 years. And if you lose your job, you typically must repay the loan within a few weeks, or you’ll owe penalties and taxes on the balance.

Again, this doesn’t mean you should never tap your home equity or retirement. You’ll learn guidelines for when and how to do it right in upcoming chapters. Just don’t turn to it as your first resort until you read up on all the potential disadvantages.

Debt “Solutions” to Avoid

One kind of loan you should be wary of is an unsecured debt consolidation loan, where a company offers you a loan not secured by an asset like your house.

The fees for this kind of lending are typically outrageous, and the loans usually just stretch out your payments, ultimately costing you much more than if you’d paid off the original debt. That’s if you get the loan you apply for at all; this area is rife with fraud and phony come-ons designed to part you from whatever money you have left.

You should approach debt negotiation or debt settlement with extreme caution as well. The companies offering these services typically promise to settle your debts for pennies on the dollar, but such settlements can devastate your credit score. That’s if you get any service at all; sometimes fly-by-night outfits just disappear with your fee. If you really can’t pay what you owe, bankruptcy is often a cleaner solution.

“Debt elimination” shouldn’t even be on your list because it’s an outright fraud. The criminals running this scam pretend that you can eliminate your obligation to repay your mortgage, credit cards, or other debt by using a “certificate” they provide—usually for a fee of $2,500 or more. They use all kinds of ridiculous arguments about the legitimacy of the Federal Reserve system, and sometimes they throw in a quote or two from the Constitution, but it’s all bunk. What you get is a worthless piece of paper that, if you actually try to use it, will trash your credit, allow the bank to foreclose on your house, and perhaps put the FBI on your tail for trying to defraud a financial institution.

If You’re Already Drowning

Most of what you’ve read so far is directed at anyone who’s concerned about debt. But if your concern has already escalated to fear or outright panic—if you no longer can pay the minimums on your debt, or collection agencies are already calling—you need to take some extra action right now.

The following game plan is adapted from my previous book, Your Credit Score, in the chapter on dealing with a financial crisis. It consists of three basic steps:

1. Figure out how to free up some cash.

2. Evaluate your options.

3. Choose a path and take action.

Step 1: Find the Cash

You have two choices—cut expenses or increase income. You may need to do both.

You also may need to go beyond the easy cuts—fewer dinners out, dropping the gym membership—to more substantial changes. Even your so-called “fixed” expenses, like your mortgage or rent, aren’t really set in stone.

I’m not saying you’ll have to move. But you should at least identify all the potential savings available to you. You may find it helpful to break those savings into three categories:

• The easy stuff. Expenses that you could ditch with little effort

• The harder stuff. Expenses that would require more sacrifice to trim

• The last-ditch stuff. Expenses you would cut only as a last resort

Step 2: Evaluate Your Options

This step actually includes a number of other tasks, all of which take a little time but that are essential to making sure you choose the right option.

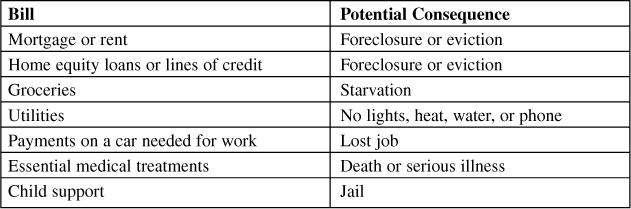

Task 1: Prioritize Your Bills

Don’t let bill collectors tell you what debts are most important. You’re the one who needs to decide.

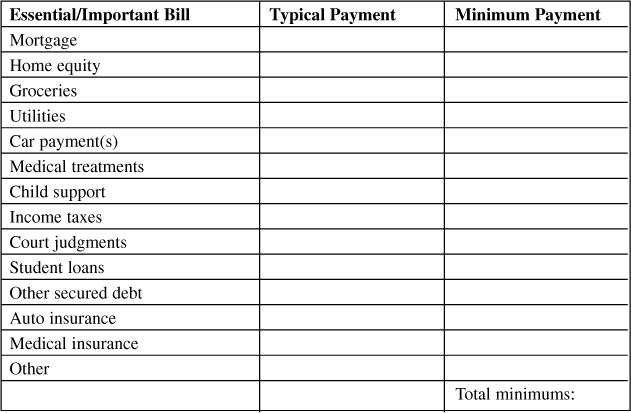

Divide your bills into three categories: essential, important, and nonessential. Essential bills are the ones that, if you didn’t pay them, there would be catastrophic consequences (see Table 2.3).

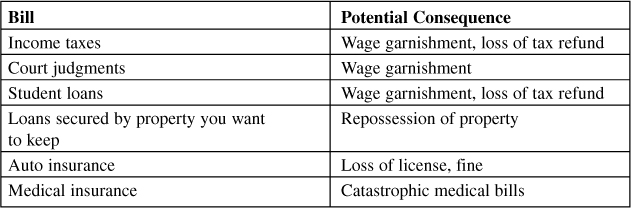

Important bills are the ones that you should pay if at all possible because failure to pay them would have serious consequences. Table 2.4 gives some examples.

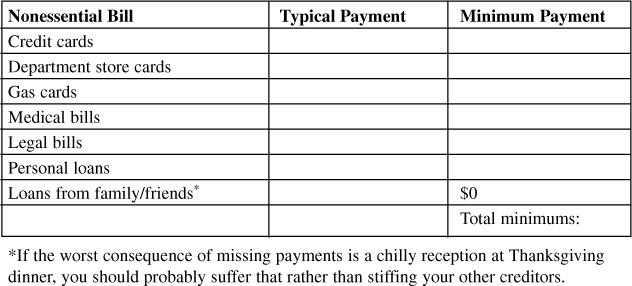

Nonessential bills include debts that aren’t secured by property. Failure to pay these debts could have serious repercussions for your credit score and may eventually result in lawsuits and judgments. But skipping these payments won’t put you out on the street:

• Credit cards

• Department store cards

• Gas cards

• Medical bills

• Legal bills

• Loans from friends or family members

You may have other bills not mentioned here; use your best judgment to categorize them.

Once you’ve got your list, go back and fill in two more columns:

• The monthly payment you typically make

• The minimum monthly payment you need to make to stay current

Task 2: Match Your Resources to Your Bills and Debts

Look at the first two categories of savings you identified in Step 1—the easy stuff to cut and the harder stuff. Then add those to your monthly net income (what you get in your paycheck after all the taxes and other deductions have been taken). Now compare that income with your first two priorities—essential bills and important bills. Can you cover the minimums required? (See Table 2.5.)

Table 2.5. Essential and Important Bills

If you can’t cover the minimums, you may have some options before opting for last-ditch cost-cutting measures. It’s frequently possible, for example, to get a forbearance on your federal student loans or to negotiate payment plans with the IRS. The first you can do yourself, usually just by talking to your lender; for IRS help, you’re probably best off using a tax pro. Even child support can be reduced if you prove to the court your financial situation has worsened, but this can take a while and may require a lawyer’s help.

Other possibilities: You could sell stuff or take that second job we talked about earlier. If you regularly get a tax refund, you could reduce your withholding to get more money in each paycheck.

If you still can’t pay for the essential and important bills, you’ll probably need to take a last-resort action, such as selling your house or renting cheaper digs. You’ll also need to consult a bankruptcy attorney about wiping out any nonessential debts because those obviously won’t get paid.

If you’ve got your bases covered and have money left over, however, you’re ready for the next task.

Task 3: Figure Out a Repayment Plan

Many calculators on the Web can help you create debt repayment plans. For now, don’t include your mortgage or the other top-priority bills we covered in the previous task. You’re just trying to design a plan for nonessential debts with the money you have left over after paying your more important bills (see Table 2.6).

First, see how much progress you can make with the increased income you identified; then add in the lump sums you’ve estimated you could raise by selling stuff. Finally, check out how fast you could get out of debt if you took some of those last-ditch options.

You also could consider—carefully—using a home equity loan or line of credit to pay off your cards. But read Chapter 11 closely before you do.

In the best-case scenario, you’d be able to retire your credit card and other unsecured debt in less than five years without too much strain. If that’s not true, however, you’ll need to consider making two appointments: one with a legitimate credit counselor and the other with an experienced bankruptcy attorney.

Credit counselors can offer plans that lower your interest charges. Although these debt repayment plans by themselves don’t affect your FICO score, lenders’ reactions to the plans may well have a negative impact on your credit. Your current lenders might report you as late because you’re not paying the full amount owed, and potential lenders might view your repayment plan as equivalent to Chapter 13 bankruptcy.

Also you have to watch out for wolves in credit counselors’ clothing. The Federal Trade Commission has found that some companies masquerading as nonprofits were charging hidden fees, lying to clients, and channeling business to their for-profit affiliates. If you go this route, you’ll want to stick with agencies affiliated with the National Foundation for Credit Counseling at www.nfcc.org.

Credit counseling is designed to keep people out of bankruptcy court. The industry is supported, in part, by payments from lenders. So you may not get the other side of the story—which is that bankruptcy might be a better option. For that, you’ll need to talk to a bankruptcy attorney. You can get referrals from the National Association of Consumer Bankruptcy Attorneys at www.nacba.org.

Step 3: Choose Your Path and Take Action

If you can pay off your unsecured debts without help, or with the help of home equity borrowing, you should cut up your credit cards right now. “What?” you might be saying. “Cut up my cards? How can I live without my cards?” News flash: People do it all the time.

If you have easy access to your cards, you’ll keep using them. Your credit cards need to be off-limits until you’re debt-free. Debit cards with Visa or MasterCard logos are accepted at most places that take credit cards; the difference is the money comes directly out of your checking account, so it’s much tougher to overspend.

You don’t need to actually close your credit card accounts, which could potentially hurt your score, unless you really have an otherwise uncontrollable spending issue.

If you need a credit counselor’s aid, make the appointment to get it done. Every day you delay costs you more in interest and puts off the moment when you’ll be debt-free.

If bankruptcy is the best of bad options, file. Some people would like to see a return to the debtors’ prisons that were a feature of American life until 1841. As it stands, however, being unable to pay a debt is not a crime. The bankruptcy laws were designed to give people a fresh start. If you’ve done your best to find money to pay your bills, but you’ve failed, you shouldn’t shun this option.

Summary

Before we move on, let’s review some key points from this chapter:

• You need to know all the relevant details about your debt before you can properly manage it.

• The rates you pay on your borrowing depend heavily on your credit score.

• Retirement savings and financial flexibility need to be a key part of most people’s financial plans, even when—especially when—they’re paying off debt.

• Some common “solutions” for debt, such as borrowing against home equity and tapping retirement accounts, often make matters worse.

• If you can’t pay off unsecured debts like credit cards and medical bills within three to five years, you may need to consider bankruptcy.