7. Auto Loans

Okay, I’ll admit it. I don’t get the car thing.

That’s abundantly clear from the vehicles I’ve owned in my life, starting with the bright blue Mazda station wagon I purchased in college, followed by the Suzuki Samurai I drove in Alaska, and the ever-thrifty little Saturn SL1 I bought with cash after arriving in Southern California. (I was so cheap at the time I refused to spring for electric locks.)

Then there was The Beast—a Ford Explorer whose odometer had turned over twice before I got my hands on it. (When we finally sold it, it had over 265,000 miles—and the new owner assures me that it’s still running.)

The SUV was a hand-me-down from my husband, who does care about cars—at least more than I do. A friend explained that the difference between hubby and me is that he was born in California, where part of the natives’ birthright is understanding that a nice set of wheels helps define who you are. As an import to the Golden State, I never got that information wired into my DNA.

If you too care passionately about what you drive, I won’t try to talk you out of your love affair. That would be futile. At best, I’m hoping to moderate your ardor enough so that your vehicle expenditures don’t wreck your overall financial plan.

If you’re somewhere in between—you want a nice ride, but you hate the high costs and fear getting stuck with a lemon—I think you’ll find plenty of information in this chapter that can improve how you buy, own, and pay for your vehicles. I hope to save you bucketfuls of money as well.

How Cars Cost Us

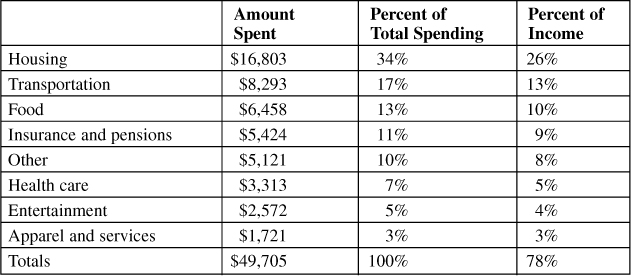

Transportation is a big part of the average American family’s budget. The costs of purchasing, fueling, insuring, maintaining, and repairing vehicles are the second-largest expenditure on average, right behind housing (see Table 7.1).

Table 7.1. Average Household Expenditures

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011

The biggest chunk of our transportation costs (more than 70% of the total, on average) is the money we shell out to actually buy or lease the car. Unfortunately, many Americans are going about these purchases all wrong:

• They’re driving into dealerships to buy new cars when they still owe money on their old ones. One out of four new-car buyers still have loans on their trade-ins, according to Edmunds.com; the average amount of negative equity is nearly $4,000.

• They’re stretching too far to buy the cars they want; 91% of all new-car loans and 85% of used-car loans are now for terms in excess of four years. With such long loan terms, it can take years for the driver to hit the breakeven point, where he or she finally owes less on the car than it’s worth.

• Gluts of used cars and incentives on new cars can make the problem worse by pushing down the value of older cars. That means as soon as you drive off the lot, your new car’s value takes a big tumble—which can make it harder than ever to reach that breakeven point.

Why It’s Bad to Owe More on Your Car Than It’s Worth

First of all, being “upside down” puts you at serious financial risk. If your car is stolen or totaled, you could find yourself without wheels and still owing thousands to your lender. (The amount you’ll get from your insurer reflects the car’s current, depreciated value—not what you paid for it.)

If you lose your job, you’ll face a similar crunch. You might not be able to make your payments, but you won’t be able to sell your car for enough to pay off the loan.

There is a type of specialized insurance, called guaranteed auto protection, that can cover the gap if your car is stolen or totaled. If you’re underwater on a car loan, you should seriously consider this coverage.

But owing more money on a car than it is worth is a symptom of a deeper problem: overspending.

People who stretch too far to buy a car cost themselves in numerous ways. The first is in interest costs: The more you borrow and the longer you take to pay back a loan, the more you pay in interest.

Then there are all the other costs associated with buying a new car. Your insurance costs typically jump; the more expensive the car, the higher the premiums. Repairs on newer cars can be costly as well, thanks to more-sophisticated technology. (If you’ve ever had to replace one of those high-intensity headlights, you’ll find that they can be 10 times costlier than a halogen headlight and infinitely costlier than the old-fashioned lamps, which cost just a few bucks.)

As one Edmunds.com executive put it, many people discover they can afford their car but, thanks to all the attendant costs, they can no longer afford to eat. The more money you spend on your ride, the less money you have for other things in your life, including vacations, emergency savings, and retirement funds. Your choices are to cut back on your other spending, neglect your important long-term goals, or go deeper into debt trying to maintain your lifestyle.

How Often You Buy Cars Matters, Too

Too many people compound their vehicular overspending by trading in their cars for newer models too often. To illustrate how much of a difference it can make to trade in cars less frequently, let’s use the example of twins Jordan and Morgan.

Jordan and Morgan each buy their first new car on their 25th birthday. Both borrow $20,000 for the purchase and pay off the loans over five years at 6% interest.

As soon as her car is paid for, Jordan buys another one—a pattern she continues throughout her life, until she buys her last car at age 75. We’ll assume that each car is 15% more expensive than the last, reflecting average annual inflation of about 3%.

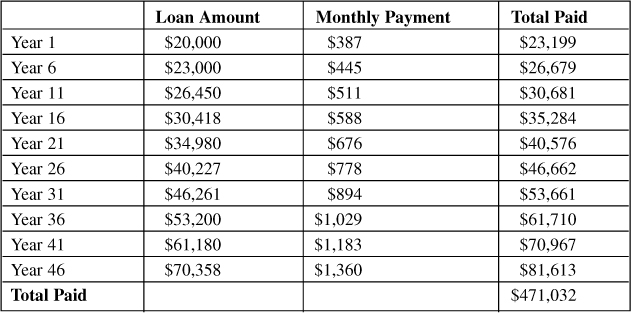

With those assumptions, Table 7.2 shows that Jordan pays nearly half a million dollars for cars over her lifetime.

Table 7.2. Jordan’s Lifetime Car Purchases

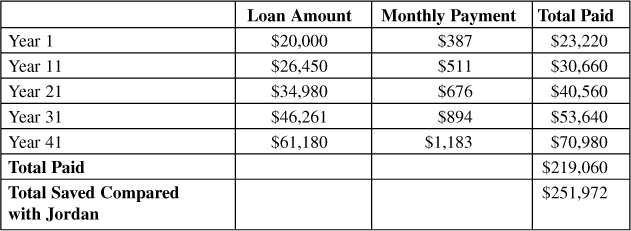

Morgan, by contrast, keeps driving her cars for another five years after the loans are paid off. She buys half as many cars over her lifetime as Jordan—and saves an impressive $251,972 (see Table 7.3). Think about that: Just by driving her cars a few years longer, Morgan saves a quarter of a million dollars over her lifetime.

Table 7.3. Morgan’s Lifetime Car Purchases

And that’s just the start of the ways Morgan could be financially way ahead of her sister.

Instead of getting loans to finance her purchases, Morgan could simply save the money that would have gone to monthly payments in the five-year period after she paid off each loan. If she did that with every car after her first one, she could save another $26,000 or so in interest costs she wouldn’t have to pay over her lifetime.

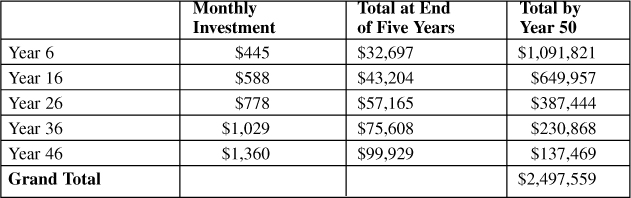

Better yet, let’s figure a money-savvy person like Morgan would take those monthly payments and invest them instead.

We’ll assume that once she gets her loan paid off, she invests a monthly amount equal to what her sister is paying for a new car. We’ll also assume she gets an average annual return of 8%, which is a reasonable estimate for a portfolio that’s invested largely in stocks.

Once again, the awesome power of compound returns is apparent: Morgan could have a nest egg worth $2.5 million by the end, as shown in Table 7.4.

Table 7.4. Morgan’s Total Savings

Obviously, we’re making a lot of assumptions here. The key ones are that Morgan is disciplined enough to invest the money in the years that she doesn’t have a car payment and that her investments earn a higher return on average (8%) than the cost of her car loans (6%).

Of course, few things are guaranteed in the world of finance. Conservative investors who don’t think they can get better returns on their money might well choose the route of paying cash for their cars, rather than getting a loan and investing their money for a potentially higher return.

The Proper Role of Cars in Our Spending

Now that you’ve digested all that, you can better understand why it’s so difficult to answer the following question:

“I recently graduated from college and want to set up a budget. I’m trying to decide how much I can afford to buy a car. Do you have any rules of thumb?”

Well, no, unfortunately. There’s really no good guideline for auto purchases, as there is for housing costs, which generally shouldn’t exceed 25% of your gross income.

Some debt counselors suggest that you keep your total debt load to 35% or less of your gross income. (Most include housing costs in that figure, even if you’re renting rather than paying a mortgage.)

The problem with that advice is that it focuses too much on monthly payments rather than on the overall cost of your debts. Someone who was paying the minimums on her credit cards, or who compressed her auto payments by taking out a seven-year loan, might be within the guidelines, while someone who pays off credit cards in full or who took a shorter-term loan might not be.

You can pretty much assume that if you’re paying only the minimums on your cards, have a car loan that’s longer than four years, and have a debt total still exceeding the 35% mark, you’ve taken on too much. But beyond that, how much of your income you choose to spend on a car is a very personal choice.

If you’re a car buff, you might be more than willing to shoulder the extra costs of buying the cars you want and/or trading them in as frequently as you can.

I just ask that you look at the total amount you’re shelling out for your wheels and see how that compares with your other spending and your goals.

If you’re saving prodigiously for retirement, have all your other important financial bases covered, and still have big bucks to spend on cars, more power to you. The point of earning and having money is to spend it on the things that are most important to us. You might well decide you’d rather own a great car than spend your money on vacations or nicer clothes or whatever.

But if you’re shortchanging other areas of your financial life or you’re going deep into debt to fuel your car obsession, think seriously about the long-term costs you’re incurring. As one of my finance professors once said, “Is it worth it to drive a Mercedes now if you have to take a bus when you’re 70?”

You should be asking similar questions if you’re considering leasing a car rather than buying.

The lease-versus-buy choice is one of those things that financially minded types love to debate. I’ll cut to the chase: If you trade in your cars every two or three years, leasing can make sense—particularly if you invest the money you save on your monthly payments.

But again, I’d recast the whole discussion. Look at the total amount you’re spending on cars over your lifetime. Now compare that amount with what you’re spending on other important areas of your life, including housing, vacations, education, and retirement savings.

I think most people are better off buying moderately priced cars, preferably used, and driving them until the wheels fall off. Having a new car every few years is quite a luxury, and one that shouldn’t be purchased at the expense of everything else.

Ways to Keep Costs Down

If you’re convinced that you’ve got better things to do with your money than spend a fortune on metal, rubber, and a few computer chips, consider the following ways to curb your transportation costs:

Don’t walk into a dealership if you still owe money on a car. You might as well just tattoo the word sucker on your forehead. Owing money on your trade-in shows you’re a financial novice who’s easily exploited—plus you’ll get stuck with a higher-than-average interest rate on any car you buy.

Know the real cost of a car before you buy. The Internet is full of car-pricing services like Kelley Blue Book (www.kbb.com), Cars.com, and Edmunds.com that can help you assess how much to pay for a car. But you should also check out the costs of insurance and repairs. Edmunds.com’s free True Cost to Own feature gives you some estimates. Many buyers also swear by Consumer Reports’ Auto Price Service, which offers research and suggested prices for most car models. (The first new car price report is $14; each additional report is $12.)

Haggle smart. Knowing what the dealer paid for the car and having a firm, but realistic, offering price in mind can help you avoid the back-and-forth “Let me check with my manager” haggling that makes many people hate dealerships. It’s essential to know the dealer invoice price for any car you want, and then to add in a dealer profit of about 2% to 3%. Bring all your research with you to show the dealership you know what you’re talking about. If you’re not good at face-to-face negotiations, try faxing or e-mailing dealerships in your area, telling them the make, model, and features of the car you’re looking for and asking them to give you their best price. You should concentrate your efforts on high-volume, well-established dealerships that welcome virtual shoppers.

Get the right financing. If you don’t have the cash to pay for a car, or if you decide you have better ways to use your money, make sure you get the best loan possible.

Your credit scores help determine your interest rate, so make sure you know what they are and what rates you can expect. The best way to find out is to arrange financing in advance with your local credit union. Credit unions are member-owned financial institutions known for cutting some of the best deals on auto loans. If the dealership subsequently offers you a better deal, you can cancel your loan application at the credit union.

There’s another thing you should know: An auto loan can do wonders for your credit score if it’s paid on time. So even if you have to pay a high rate now, you may be able to refinance to a lower rate in a year or so (as long as you have some equity in the car).

Buy cars that are two or three years old. Let the first driver take the depreciation hit. The cars you buy may still be under warranty, and you’ll have a nice ride for a lot less.

Some people are worried that they’ll get a lemon or a car that’s been abused by its prior owner. But you have plenty of resources available to help you pick a good used car that you won’t regret buying.

In addition to its vehicle-specific reports, Consumer Reports puts out an annual list of the most reliable used cars.

Before you buy a used car, get its vehicle identification number from the dashboard or doorpost and run a report from a car-tracking service like CarFax or AutoCheck. These reports (which cost about $30–$40 for one or $45–$55 for unlimited searches) can help you spot a rolled-back odometer or other serious problems, like a “title wash” (which is when a car that’s been in a serious accident is issued a new title in another state to try to hide its history).

A trip to a mechanic before you buy can help rule out any major problems. If you’re still concerned, investigate buying a “certified” used car (but check the details of the certification program because some are better than others).

Don’t agree to a loan that stretches over more than four years. You can help make sure you don’t overspend on cars by paying them off within three to four years.

Longer-term loans may offer lower monthly payments, but you’ll pay more over the life of the loan. If you can’t afford to pay off the car within four years, you probably need to consider a less expensive vehicle.

Avoid loans with prepayment penalties. These have become more common, particularly if you have troubled credit. An auto loan, if paid on time, can help rehabilitate your credit score, which should in turn help you refinance to a better rate in a year or two. Lenders that want to avoid losing your lucrative business impose prepayment penalties to make it much more expensive to get out of your loan. Prepayment penalties also increase the cost if you want to try to pay off your loan early.

Try to drive the car as long as possible, but for at least a year after you’ve paid off the loan. Cars are better built than they’ve ever been, and some can rack up hundreds of thousands of miles and still not be ready for the scrap heap. If you invest money in oil changes and other appropriate maintenance, you can easily drive a car for 10 years and be money ahead.

That surprises some people, who think that once a vehicle hits a certain odometer mark the repair costs automatically skyrocket.

The reality is that even when a car does start to spend more time at the mechanic’s, you still often spend less than if you took on new-car payments. The tipping point for most car owners should be reliability, not odometer readings. If you’re reasonably confident your car will get you where you need to go, there may be no reason to trade it in.

If you’re currently “upside down” on a car, try to “drive out” of the loan. L. R. from Houston wrote: “I have a Nissan Maxima that is in pretty good condition. Currently, I owe $21,820 on the loan but the car is worth only $12,820. I am willing to get a less expensive vehicle, used, and put some money down. What do you think I can do to get out of this car/loan?”

Trading in the car for something cheaper typically won’t reduce the amount you owe and usually exposes you to a higher interest rate because part of your loan will be unsecured debt.

If you can afford the monthly payments, the best way to cure an “underwater” car is to simply keep it until the loan is paid off. This is called “driving out of the loan.” You can speed that day along by making extra payments (provided that your loan doesn’t have prepayment penalties). The Houston reader might take the money she would have used for a down payment on another car, for example, and apply it to her current loan.

If you can’t afford the payments, you might talk to your lender about a loan modification that reduces your monthly cost while increasing your loan term. That will raise the total cost of your car, of course, but that’s usually preferable to repossession, which devastates your credit scores. (Turning in your keys voluntarily, by the way, is still considered repossession and will knock your scores for a loop.)

Also, if you’re underwater, protect yourself with insurance that covers the gap between what you owe and what your car is worth. Many insurers offer guaranteed auto protection (GAP) coverage as an add-on to your regular policy, typically for a monthly premium of $10 to $25. Dealers, banks, and credit unions also offer the coverage, either as an add-on to your loan or as a one-time fee that can range from $100 to 5% of your car’s value.

Summary

Spending too much on cars—and borrowing too much to pay for them—can wreak havoc on your financial health. One of the best ways to reduce your auto finance costs, if you don’t want to pay cash for your vehicles, is to keep your loan terms relatively short and own your cars longer.

Credit Limits

• Car expenditures are a choice. There’s no good rule of thumb about how much you should spend. It depends largely on how well you’re meeting your other important financial goals and how important your ride is to you in relation to your other spending.

• Consider owning your cars longer. You can save hundreds of thousands of dollars over your lifetime simply by keeping your cars a few years longer before you trade them in.

• Don’t walk into a dealership “upside down.” Pay off the car you’ve got before thinking about buying the next one.

• If you can’t pay it off in four years, you probably can’t afford it. A five-, six-, or seven-year loan typically means that for years you’ll owe more money on the car than it’s worth—which increases your financial vulnerability (not to mention your overall financing costs). You definitely don’t want a loan that lasts longer than you’ll own the car.

Shopping Tips

• Know your credit scores. Auto lending is strongly driven by scores. If you don’t know yours, and the interest rates to which you’re entitled, you can get stuck with a much more expensive loan.

• Do your research before buying. Save money up front by using Internet resources and Consumer Reports to find the best values.

• Look into refinancing. If interest rates have dropped, your scores have improved, or you got talked into a too-expensive loan, explore the possibility of swapping your loan for a cheaper one.