What is Fun Anyway?

It is impractical to start off a book on games design without spending at least some time trying to define what we mean by a “game,” and how that relates to “fun.” It would be easy to spend the majority of this book exploring the different concepts and ideas behind game theory. However, rather than doing that, I’d like to point you in the right direction to find out for yourself. In this chapter I’ll refer to other writers and provide references in the endnotes for people who have looked into the theory of gameplay from traditional games all the way to modern computer games and if you feel you need to know more, please check out their work. Whether you are familiar with the concepts here or not it’s well worth taking time to step back and to consider these questions. But where should we start? The very act of definition seems to suck out the life of what it means to “play.”

Can You Define Fun?

Saying that Fun is “enjoyment, amusement, or lighthearted pleasure” doesn’t help us understand how it feels to laugh or what triggers within a game can delight us.

The easy answer might be to quote some inspirational game design guru like Rafe Koster.1 In his A Theory of Fun he tries to get us to go back to basics and to consider the way our brains reward us for success in pattern-matching. Pattern-matching is a cool way to start. We see two blue gems alongside a green gem, we know that if we can get a line of three blue gems we will get a reward, and as long as the grid of gems changes, we continue to get pleasure from the process of finding such matches where we can.

It can be hard to accept this fairly reductionist way of thinking about games. For example playing poker isn’t the same thing as playing chess or a classic match-three style game like Bejeweled. There are nuances of social interaction and decision-making based on predictions of probability in poker, but even these are in themselves forms of pattern-matching. Texas hold ’em players talk about the board texture based on the “suitedness” and “connectedness” of the flop.2 Chess, as it has evolved, involves no random influence except the strategies of your opponent, but again the patterns of the play of the finest players has been detailed and classified over hundreds of years and many players will instantly recognize shapes of moves made in the opening, mid and end game sections of play.

At What Price Victory?

Patterns in games are extremely powerful. When trying to create games as a service they are fundamental. We need a game to have something at its heart with a highly repeatable pattern. It’s almost like the heartbeat of our game or the meter of a song.

The trouble is (as Koster goes on to state) pattern-matching can become boring.

Writers like Johan Huizinga3 and Robert Caillois4 proposed that “rules” form a key factor in helping us to turn the pleasure of pattern-matching into something we could term “play.” They create structure and ways to validate our behaviors, whether that applies to sports or games. Rules have to be something that are agreed by the participants and that help us make sense of the experience, allowing us to differentiate what is play from what is not.

Key to these rules is the creation of “victory conditions,” something Scott Rogers5 includes in his definition of what makes a game.

Then, of course, if we accept that there are victory conditions, then it’s probable that we also have to accept that there are failure conditions too. Jesper Juul6 writes about the paradox inherent in knowing that we will experience failure and that we still seek to overcome it is what drives our interest in games. Greg Costikyan7 uses the example of Space Invaders to show that, even where the final outcome is inevitable defeat, players can delight in the playing, not to win but to better their previous score or that of another player. He further argues that a game’s outcome can be more than just a binary “win” or “lose.”

Many writers also talk about the psychology of games, and as much as I want to be scientific about this, I don’t know enough about brain chemistry to be sure whether fun is a chemical response with a dopamine or serotonin release following the successful overcoming of a challenge. But clearly it can be valuable to consider how normal brain responses are triggered from the way a player engages with our game.

Play is Utterly Absorbing

In the end I personally find, despite being written in 1938, Huizinga’s definition of play to be extremely useful and I think we can learn a lot about what makes for good game design by analyzing it further. He talks about “play” as “a freestanding activity quite outside ordinary life … absorbing the player intensely and utterly.”

Think about that for a minute. When we suspend our disbelief and allow ourselves to dwell in the world created by a game experience we gain an amazing release. We free our imagination and creativity to explore and focus on the patterns of whatever it is we are doing. It’s almost like we are giving ourselves permission to play. We experience this kind of release when we read a great book, or watch our favorite soap opera. This works whether that is just for a few brief delightful moments of casual play or for the hours we set aside for our favorite hardcore console game. This suspension of disbelief comes from a mutual agreement between the designer and the player. We, as designers, have to create the conditions where the player feels comfortable to accept the rules of that world and we have to keep consistent with those rules to avoid breaking the immersion, or at least limiting those breaks to predictable patterns.

No Material Interest

Huizinga’s definition continues by saying that play is an activity with “no material interest or profit gained.” That’s a bit more challenging, especially where we want to sell virtual goods to the player. But perhaps this helps us gets to the bottom of the negative feelings that we talked about with the Free2Play (F2P) model in the introduction. When players feel that we are only interested in the money we can gain, then is there any wonder that this will feel like a breach of trust; perhaps even feel like we have “broken the rules?” If you can buy your way to success then we remove the challenge and essentially create a method to cheat the victory conditions. I have found this myself in several games where the purchase of virtual goods essentially undermined the purpose of the game mechanic. Why would I want to spend money on in-game grind currency when that very currency was the only meaningful measure of how successful I had been in playing the game?

Crass Commercialization

It is also the case that constant reminders to buy things can stop us from “absorbing the player intensely and utterly.” However, when we look at the raw data of how players respond to in-game reminders, this shows that instead of causing players to leave or “churn” from our game, instead we see that “push promotions” can be really effective. Does that mean Huizinga was wrong? I don’t think so. The problem is often that there are multiple motivations at play. Players understand that games are commercial properties and often accept that we want to sell to them, but this will still annoy a number of them. Looking at data from some social mobile games it seems that promotions that are in-line with the flow of the game generally perform better. Where possible we should try to find the balance between the need to inform players that it’s worth investing their money in the game without breaking the illusion of the game experience.

Farming for Gold

On the other hand this idea of “material interest” is also about what the player themselves might gain. Removing the idea of profit from the definition of “play” helps us consider the phenomenon of gold-farming in MMO games. We can clearly argue that this breaks the fun of the experience, at least for the people gold-farming. However, for the people paying for the extra gold or to eliminate the grind in order to gain access to the higher level playing experiences, this can be an absolute delight. Many games, such as RuneScape8 spend a lot of time trying to minimize the impact of gold-farming, but the question in my mind is whether this activity is essential to preserve the game or a symptom of an untapped demand. What if instead you provided a system to encourage players to gold-farm inside the game and take a small percentage on each transaction? Similar questions apply when you start thinking about the creation of user-generated content. When does this cross the line between creative entertainment and work? Should creators have the opportunity to be paid with grind-money or in-game virtual goods for taking the time to make things in the game? Should they be paid with real-money?

This seems tempting to me, but it does seem at odds with the concept of “material interest.” Then there are other complications, such as the legal requirement to prevent money-laundering involved with any real-money transactions.

Gambling With Players?

What is clear to me is that when “profit” or “material interests” impact play, our motivations change. The more personal gain affects our play, the harder it becomes to suspend disbelief.

This question will have a profound impact on the way game companies embrace real-money gambling in their games. As the USA opens up to gambling services, like the UK before it, we will see a “gold rush” for gambling games, but at the risk of blurring two very different playing motivations.9

Counting on Uncertainty

In 1958 Roger Caillois, in his Definition of Play, expanded on Huizinga’s description of play and suggested that doubt itself was a vital part of the process of play. If there is no uncertainty then play simply stops. This applies to games of skill as well as luck, because if the players aren’t sufficiently balanced there is no pleasure in the game, as much as if there is no chance of failure or success. Although it is possible that some fun can be achieved through the process of play if there is room for personal impact on the outcome. For example, the fun of playing FarmVille is not found in the creation of your farm, but in the journey of making it your own. Juul in his 2013 The Art of Failure expands on this by asking us to consider the “Paradox of Painful Art.” We wouldn’t seek out situations that arouse painful emotions, but we recognize that some art will evoke a painful emotional response and yet we still seek out that art. Similarly, we don’t seek to experience the humiliation of failure, but we know that playing some games will result in such a failure and yet we seek out those games as long as we perceive that we have to potential to overcome those goals with practice. Indeed it’s the fine balance of challenge and perception of the potential for success that makes a great game impossible to put down. It’s worth checking out Greg Costikyan’s Uncertainty in Games if you want to see how these concepts apply to different classical games from Super Mario Bros to The Curse of Monkey Island.

Playing Together Alone

There is a public perception of games playing in isolation with a computer is very new and reading Huizinga’s work further we see that in his definition of play is the idea that this “promotes the formation of social grouping which tend to surround themselves with secrecy and to stress their differences from the common world by disguise or other means.” I find this perspective fascinating not least because this predates Facebook and computer games in general, but it even predates games like Dungeons & Dragons by 36 years.

The Cake is a Lie

Think about the way hardcore computer gamers have their own shared memories and affinity to specific platforms and characters. For example if I say “the cake is a lie,” most of you reading this will know exactly what I’m talking about and may even have strong memories of a particular song. There are of course a lot of people who won’t have a clue what this refers to and indeed who are effectively excluded because of this. Inside knowledge is an important aspect of belonging to a group and becomes a shortcut to sharing the fun when we play. It’s also a factor that I believe has largely been overlooked in social game design in recent years.

We Want to Play with Others

Social interactions are vital to playing games. Indeed the idea of playing with others is a key survival trait exhibited by countless social mammals. It allows us to be able to test and trial experiences as well as working out your place in the pecking order without the risk of being harmed in the process.

Since 2008 the idea of a social game has changed dramatically with the arrival of Facebook-based games and the way this innovation dramatically shifted the size and nature of the games playing audience. Zynga and Playfish essentially made it possible for games to reach mainstream users and for the first time made playing games something that almost everyone did. Key to this change was the nature of the platform. It only needed a browser, it didn’t require an upfront fee and, because it allowed us to share playing moments everyday with people who matter to us, this unlocked supersized audiences. Of course most of these players had never learnt the “rules” of game-playing and indeed arguably had rejected the very idea of play. At the heart these games had to be simple, repetitive, playful moments; they couldn’t get a new audience who had previously rejected computer games to adopt the often complex and obscure mechanics many experienced gamers take for granted.

But are These Games? Are They Social?

We will talk about degrees of sociability in a later chapter, but I would argue that what makes Facebook games work, indeed the genius part of Facebook itself, is its power to deliver asynchronous communication with people who matter to us. We don’t have to be at the same place or the same time to be able to share meaningful moments. It is like we are leaving footprints in the sands of time for our friends to discover whenever they are in the mood to find out.

There have been lots of issues since the golden age of FarmVille and Restaurant City, not least the decision by EA in April 2013 to close SimCity Social, Sim Social and Pet Society. But I don’t want to turn this chapter into an analysis of why I think we have seen decline in this area. Instead, I want us to focus on what this concept of social interaction means for game design and the way asynchronous play can vastly broaden our horizons—provided the interactions are meaningful and personal enough.

One of the areas that has regularly been brought into question when considering the Facebook game is where there might be room for failure and challenge. Something I would argue was largely absent from this generation of social gaming and that I expect will come back in the next generation of Facebook-powered online games.

People Are People No Matter What They Play

Of course when we introduce social play we have to consider the way we interact with other people. Richard Bartle10 has spent a lot of time looking at how people react with each other and how these behaviors impact on how they play games. He looked at the ways people played the first virtual world, the original online text-based Multi User Dungeon (MUD), and used this to isolate four essential player types. These types were defined to help answer the question of what players wanted from MUDs, but has a remarkable relevance to online worlds and to games as a service in general. Looking at this crudely you could say that “achievers” are looking to resolve in-game goals and are essentially motivated by success. “Explorers” gain enjoyment intrinsically from the act of moving through the world and collecting items and information about the world, the completion of the game’s goals are less relevant that the knowledge of where those goals occur. “Socializers” are often less motivated by the inherent mechanics of the game and often use the game as an excuse to meet and interact with others. The last category were named “killers” but you could easily call them by the name used on internet forums, “trolls.” They actively enjoy the ability to disrupt the play of others and to exploit methods in the game to create unexpected results (even to bring down the servers).

Understanding Motivations

What I believe Bartle is showing us is that players exhibit different reward motivations and it becomes vital to us to understand these different motivations as we try build and maintain a community. We have to anticipate and manage (ideally redirect) the latent frustrations of the killers to avoid them becoming disruptive. We have to have goals and variety for the achievers and explorers respectively to complete that don’t simply come to an end after just a few hours of play. We have to create the context for socializers to be able to communicate and create the social glue that sustains your community.

Understanding the range of emotions that we create through play is essential but we still have to simplify these into terms we can communicate easily to others, the press, our investors, our team, and—importantly—to potential players too. That means we also need to consolidate all these ideas down into two deceptively difficult questions. What is our unique player proposition (the core reason why players should care about our game from a purely gameplay perspective) and what is our unique sales proposition (the reason why our players should convert to being regular payers)?

Fun isn’t Limited by Technology

I guess my point in all of this is that fun is a basic human emotional response to play and the principles of our behavior have only superficially changed over time. We may have handheld devices and cloud computing, but in the end we still play as a free activity, with no care for material profit. Fun is not something that can be forced. It requires a separation from our normal world to exist, usually framed in some commonly agreed rules with some level of uncertainty to its outcome and it’s something we want to share with other players. Understanding this and allowing us to consider the implications this raises as well as the harder questions of business models and marketing is what makes our job as designers so much fun.

Notes

1 Game designer Rafe Koster’s A Theory of Fun is a great inspirational text for budding game designers. Check out www.theoryoffun.com/index.shtml.

2 If you are interested in poker theory, check out this post from “Pokey,” which talks about poker strategy in detail, http://archives1.twoplustwo.com/showflat.php?Cat=0&Board=microplnl&Number=8629256.

3 Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga wrote about “play theory” in in 1938 with his title Homo Ludens, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_Ludens_(book).

4 In 1961, French sociologist, Robert Caillois published a critique on Huizinga’s work in Man, Play and Games, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Man,_Play_and_Games.

5 Scott Rogers talks about game design in his book Level Up: The Guide to Great Video Game Design. Check out his blog at http://mrbossdesign.blogspot.co.uk.

6 Jesper Juul talks about games as the “Art of Failure” and the paradox of tragedy in relation to video games. His blog can be found at www.jesperjuul.net/ludologist.

7 Greg Costikyan has worked on traditional and computer games as well as Uncertainty in Games http://mitpress.mit.edu/books/uncertainty-games.

8 The RuneScape team spends a lot of time trying to reduce the impact of gold-farming on their service, despite being a F2P game, http://services.runescape.com/m=news/anti-gold-farming-measures.

9 I believe that gambling has a very different set of motivations and rewards based on the tension between the result being in and the player knowing whether they have won or lost. This anxiety seems to be heightened by the importance of the stake. Success is generally attributed to personal choice, whereas failure is generally attributed to “bad luck.” Unlike non-gambling games, this sense of reward doesn’t diminish with repetition and hence, I suspect, players will be more vulnerable to addictive behaviors (of course addiction is a massive topic itself on which few experts agree).

10 Richard Bartle, Professor at the University of Essex, co-creator of MUD and author of Designing Virtual Worlds, www.mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm.

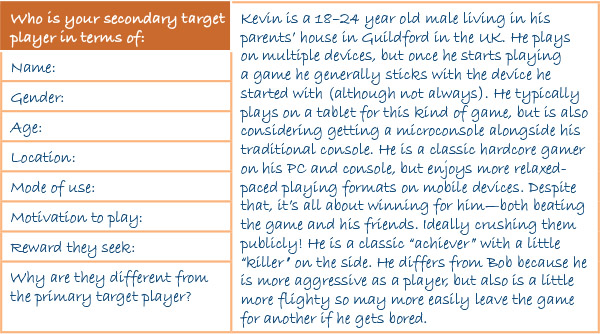

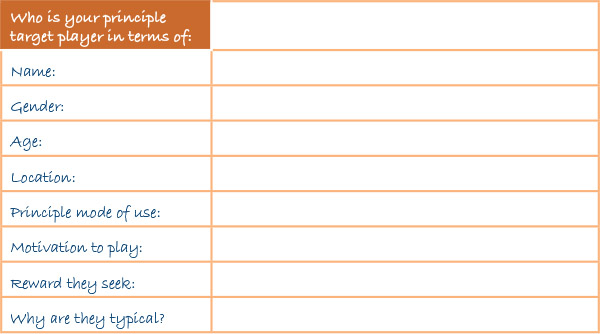

Exercise 2: Who Are Your Players?

In this second exercise we want to consider our audience. We need to identify a selection of different personalities to help us ask questions about our ideas in a useful way. Ideally, these personalities would be based on real segments of our playing audience, but for the purposes of this exercise I will assume that we don’t have access to that data yet, not least as we have yet to make our game. When we can use real data we should. This approach is a thought exercise designed to make it easier to question our own ideas as much as to consider the perspectives of other players. With games as a service you are not just making a game for yourself.

For this exercise to be useful we need to be able to put ourselves into the shoes of other players. This mean we need to understand something of what motivates them, who they are, how much experience they have, and, above all, what motivates them to play at all, let alone to play our game. To help with this we will create a stereotype personality based on their age, gender, and background. We want you to build up a picture of them and try to think of people you know, ideally people who have different interests and needs to your own. Then we will add to that by considering their playing experience and motivations to play.

Richard Bartle’s player types form a great model for this, but are not the only way to categorize the reward motivations of players and we should feel free to expand on this kind of thinking. We should also consider the principle mode of use (on-the-go; in their front room; on the toilet, etc.) for each player as well as their mood or current objective in playing (escapism, distraction, collection).

It’s really important to give them a name. This is a tool that helps you isolate their needs in your own mind and indeed to give yourself permission to question your own ideas safely; because it’s about what that “person” would feel. This may sound trivial, but it’s quite a profound thing in allowing your own inner questions about the game to come through.

Let’s start with your principle player, the one who is your ideal target and who will probably be the most typical player of your game.

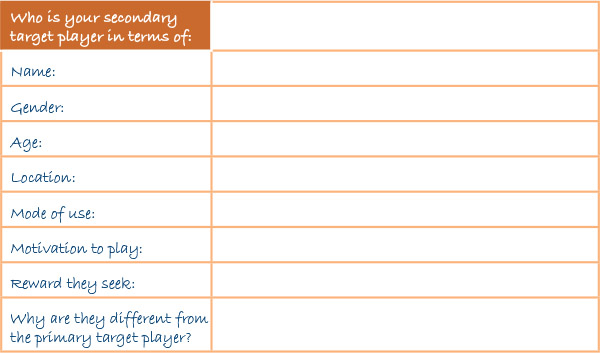

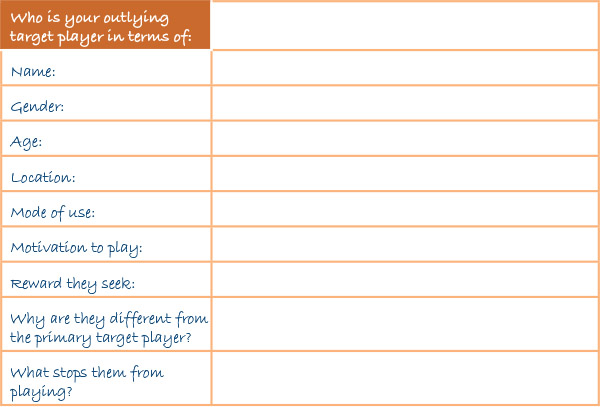

Next we need to come up with a contrast. This should be a player with different needs, but who still has good reason to play your game, even though this is different from our principle player.

Often two personalities can be enough to help provide �contrasting views, but I also like to have a third, the “outlying” player type. These are players who might play your game if only you considered their needs a little more. They should be more different still than the target and secondary players and represent a wider more mass-�market audience in most cases (if you have a mass-market concept then instead these should represent more “hardcore” players). This personality should not be the same gender as both the previous �personality types.

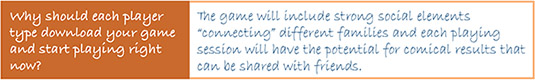

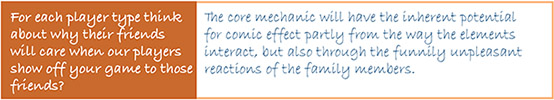

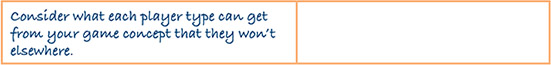

Finally, let’s use these player types to consider how your concept might deliver a unique playing proposition for our audiences. Essentially this is about what makes the game fun for your players (and not just for you!). This might be quite difficult to answer at this stage and you may want to come back after progressing further into the book. Alternatively it might be worth returning to the concept and changing one of more of the features of the concept.

![]()

Worked Example: