Getting Engaged

In Chapter 4 we talked about how understanding the “soul” of games as a service comes from thinking about the evolution of a player through their different life stages. We continued this theme in Chapter 5 when we tried to not only map out that the changing nature of engagement by thinking about the different cogs and loops we use in games to maintain and sustain the interests of the players over that lifespan.

All of this has been an attempt to get you thinking about player engagement and to understand that by acknowledging the player flow we can build on their engagement without accidently breaking it when it is at its most fragile, by asking for money or social sharing at the wrong time.

Thinking Differently

In this chapter we will explore the concept of engagement-led design in more detail and look at some specific tools we can use to build mechanics that respond to the player’s evolving needs. This isn’t intended as a prescription to define a formula for game design but is intended instead as a tool to help you review your game designs and to identify potential problems as well as ways to punctuate each stage of play with experiences that can help build deeper engagement, perhaps even to “upsell” players to the next life stage, to spend money, or simply to keep playing.

In Chapter 5 we identified the need to grab the player’s attention in just six seconds and lead them to a meaningful success within the first minute. But how do we do that; what design principles can we use to deliver on something like that?

The Bond Opening

Let’s take an analogy from the film industry1 and look at the James Bond movies, which always deliver a spectacular opening moment.2 Within the first ten minutes or so we are treated to a condensed experience with all the guns, girls, chases, cars and, of course, quips that we expect from the genre. This isn’t a random indulgence. This reintroduces us to Bond himself, what he does and, importantly, just what he is capable of at his best. It’s a benchmark against which his abilities are measured, allowing us to understand the difficulty to overcome his opponents later. The story of that opening is separate from the rest of the plot. This moment is about setting up the conditions that allow us to make sense of the plot later in the story, hopefully without giving anything important away. This is about explaining the environment of the world Bond lives is. Then it ends with a classic staged moment, we look at the archetype “licensed to kill” spy down the barrel of a gun. This reinforces the continuity between the films and whoever is playing Bond on that occasion. It’s a level of familiarity that creates a concrete connection between the viewer and the film, settling everyone into place for the journey that is to come. This approach makes us willing to forgive all kinds of incredible or flawed plots as it gives us permission to turn on our “suspension of disbelief” and turn off our critical thinking.

What has this got to with games? Well it provides us with a perspective we can apply when we look through the first moments of our game. We should try to work out what qualities the opening experience has to delight players and importantly whether they foreshadow3 the value of playing our game. This starts from the moment that the player selects the icon. We are setting expectations with the art style, the UI and how smoothly this functions. The way we explain to players what they need to do to play the game matters and should feel part of the experience. In fact I’d go further: it has to delight the player. If we have a boring, frustrating tutorial, this risks setting an expectation that we have a boring frustrating game. Instead we should try to eliminate the need for a tutorial and use play to educate the player in the ways of the mechanics as far as possible.

A Core Experience

The early stages of a game should clearly communicate the core mechanic (what we earlier called the “bones”) of the game and this means we have to also clearly communicate the success criteria (the “muscles”), which at the same time means we have to explain the values of the game, which are intrinsically linked to the reasons why we should keep playing. Games such as Assassin’s Creed take a very direct approach to this by giving us the chance to play a fully equipped and skilled avatar in the first stages of the game, only to take away much of those perks so that we can earn them back again. On the other hand, Plants vs. Zombies 23 uses a pattern of play that starts simply and draws you across the map for each level, allowing you to quickly unlock a series of new seeds you can use. This demonstrates the route map through the game, before you are informed that to proceed to the next “world” you have to collect a specific number of stars. This asks you to repeat the journey you have already made, but with a new end-goal as well as new twists to each stop on your journey. Both these techniques provide the player with a degree of freedom, a sense of purpose, and the opportunity to take a step-by-step journey of discovery that gives them the opportunity to learn and perfect the controls without this being too scary. Further, they use these steps to create entertainment, genuine fun as well as genuine progression punctuated with regular and early playing rewards. These are not just meaningful to sustain every player, but they also set up the expectations for later in the game. From this groundwork, the player will understand whether, for them, the game is worth spending money on later. Don’t ask players to spend money at this point, however; the point of this stage is to demonstrate the value of the game to them so they are much more inclined to buy at the right stage in their engagement. That being said, this is an opportunity to lay our cards on the table; that our game is worth spending money on. We want to make sure that even in only the first minute that we are explaining that we have a great game, that there are things about this game that are worth spending money on, but only when the player is ready to do so.

Reasons to Trust

Let’s also not forget the importance of communicating the core values of our game’s brand and that we should ensure that our use of art style, the emotions of our story, the way we sound, and, of course, the core gameplay combine to set expectations that will be lasting. Part of the reason why it’s so important to paint such a good picture of our brand is that these first impressions last. James Bond is a brand, he represents specific qualities and an identity that, despite the terrible things he has to do, remain something to aspire to; admirable despite his attitude towards women. It doesn’t matter if he is being played by a different actor or if the role takes a comic or dark tone. Bond is an idea that goes beyond a logo or icon. Like other strong brands, Bond has become shorthand for all of the qualities we want people to think about when considering the ultimate, elegant spy. What is the equivalent for your game? What are the qualities you want to communicate about your game? How does each element from art to camera, from mechanic to narrative all help to build up this identity? And why would your players think of your game when reminded of those qualities in the rest of their life?

Easier Said Than Done

Building a brand is not an easy thing to pull off. There are very few truly famous games brands out there. However, those that exist carry with them values and expectations of a playing experience that we understand instantly. I only have to say “Lara” and most gamers know exactly who I am talking about, and I don’t mean the classic cricketer.4 Don’t expect that you can create a brand that will be the next Sonic the Hedgehog or Angry Birds. That kind of brand requires an incredible alignment of luck, timing and usually a huge and well-spent marketing budget. However, thinking like a brand is still really important and its impact on the quality of your game and the expectations of your player will be enormous, as well as helping you to coordinate your promotional messages about the game.5 The required consistency of art, design, writing style, PR messages, etc., will pay dividends and should be rooted deep in the concept of your game and what makes that unique and compelling to players.

The Flash Gordon Cliffhanger

After the Bond moment, and assuming that we succeeded getting our audiences’ attention, we then have to consider how we will encourage them to keep playing. I can’t stress too strongly that the core differentiation between a product and a service is about “repeated engagement.” So what can we do to build or better still consolidate that repetition? Let’s take another analogy from the film industry. The Saturday matinee serial was the mainstay of the 1930s with actors like Buster Crabbe, who played eponymous classic characters from Tarzan to Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers. The writers of these classics knew that they had to satisfy their audiences with incredible, self-contained stories that would not only delight them, but keep them coming back each week for the next episode. The writers had to leave the audience desperate for more each week. The trick of having a never-ending story goes back at least as far as One Thousand and One Nights and continues to be used in many modern TV series,6 perhaps most notably the original Dallas when we all wondered “who shot JR?”7 You could arguable that the Kiefer Sutherland-fronted series 24 turned this into a fine art, with every moment created to deliver a new and deeper twist.

Gordon’s Alive?

There are so many alternatives but, although I’m tempted to bring up Doctor Who, it will always be Flash Gordon that sticks in my mind. I remember as a kid watching reruns on a Sunday afternoon of Crabbe’s famous character in glorious black and white, fist-fighting with one of Ming the Merciless’ henchmen only to fall to his apparent death from the spaceship. Then in the next episode he would have suddenly have grabbed some protruding pipe and survived. It was all a bit ludicrous but finding out how he survived and how badly that scene was put together8 is all part of the fun. However, what’s important here is the build-up of tension and the creation of a perceived peril. We might have known that Flash would survive, but our suspension of disbelief allowed us to the luxury of wondering how he could survive the latest death-�defying moment. This format didn’t just have to be about life or death, the writers could mix it up with love interest (would they kiss or not?); would the hero kill his enemy? Was the enemy really dead? Leaving an ambiguity about the end of an episode meant you could revitalize any subplot in later episodes and has been the model for soap operas around the world.

We need to look at each playing session within our games as if they were a Flash Gordon episode. That means that they have to be inherently satisfying and make sense to the player. The activity in the session needs to draw the player inevitably onwards towards a greater objective (such as defeating Ming the Merciless) while dealing with the current goals (such as negotiating with Prince Vultan of the Hawkmen). However, we need to end the session with the player wanting more and giving them a reason to return for the next session. Indeed we could use this concept to help us mix up the rhythm of play, creating the gameplay equivalent of a musical “bridge.” This idea of a contrast to the overarching composite of patterns of play is an appealing idea as, while it shakes up our preconceptions of the game, it still remains intrinsically integrated into the experience as a whole.

Building the Arch

So what is your equivalent of the long term story arch? With a game like Candy Crush, not only is the narrative journey literally drawn out as a pathway for you, it also has an “energy” mechanic variation that uses up lives every time you fail to complete a level. Each playing session has a unique layout and rule variations that challenge you in different ways and of course you recover your lives at a slow rate. We can continue to play levels we know how to solve as long as we want, but to move on we have to risk our “lives.” In Firemint/EA’s excellent Real Racing 3 we are drawn forward by our ability to progress through numerous race courses and access more cars and different races. However, racing has a natural consequence, causing wear and tear to our vehicles, which impacts their performance. Both of the game examples I have given you are using a variation on the concept of “energy.” However, as I said before I don’t want to focus on that from the point of view of using it to earn money. At this time I don’t even want us to consider these techniques as a way to introduce consequence for “failure.” Instead I want you to think what this means from the point of view of getting the player to come back to the game after playing it for some time.

The BlackBerry Twitch

Getting players to come back to the game can’t just rely on whether they enjoyed the initial session or not. There have been many stats quoted about this, but sadly I can’t find a reliable source to quote. However, something like 85 percent of apps never get played twice. If I am waiting for my lives to replenish or for my repairs to complete, that makes the time I wait part of the strategy of play. The more I return to the game, the more I engage with the game, and the greater likelihood that I will want to invest in the larger story arch of the game, whether that’s making my way to the Lemonade Lake or becoming the best racer in the Muscle Car category. These techniques rely on the subconscious awareness that something is going on inside the game and I’m not getting to be part of it. This sense of “missing out” particularly applies when a game has strong and meaningful social interactions. The use of notifications can provide a great reminder of activity in the game, but you have to be careful to make sure that this is valued and appreciated, otherwise it can become a little like a “CrackBerry” and become annoying. Having too many nagging notifications is a reason to delete an app, not to return to it.

Real-Life Interruptions

While we want player to return, we can’t control the frequency at which they do so. Indeed we can’t control the circumstances when they quit playing any given session. Players don’t even have the same needs every time they pick up our game and the differences in their mode and mood will (as we discussed in Chapter 5) have implications on the duration, focus, and flow of each playing session. Sometimes the player will be looking for a quick fix or an excuse to escape from the circumstances they find themselves in, such as boredom on the train or perhaps a mind-numbing activity at work. Of course that would never be to avoid having a conversation with their partner … honest. To cope with all of these external needs, we have to make sure our game has natural moments where the session can end and still be left in a way where it matters that I come back later.

The Flash Gordon cliffhanger is a great tool to help us think about how we can help each playing session to deal with these differences. This is particularly important for mobile or tablet games, but thinking about this can benefit all game designs. If we know that the flow of play might be interrupted and we still deliver the means to lure the player back then we will end up with a more compelling experience. The methods we use to draw players back might use narrative, be based on a game mechanic, even be socially driven. But the important thing is that we think about how we get players to come back to the game. That’s imperative.

Never Seen Star Wars?

The next movie analogy is a little less directly about the film itself, more about the subculture that has grown up around a blockbuster series of movies. The original Star Wars had as much as cultural influence on my generation (and many that followed) as any other movie, indeed it’s hard to find many equivalents in any media. Its influence on games players is probably due to the coincidence of the timing of the market introduction of video games in a similar timeframe as the release of the original movies. Star Wars captured my imagination as an eight-year-old sitting in the cinema and to be honest it still does, despite the damage I would argue Lucas has done to the brand over the past decade. I’m not alone. Indeed almost every aspect of popular culture has been affected in some way by the events in a galaxy far, far away. But there are many people who have never seen Star Wars. Including my wife. Yes, as shocking as it sounds, my wife has never seen Star Wars. It simply doesn’t interest her, largely as she knows there is no way it could live up to the expectations I have set up in her imagination. Yet she loves Lord of the Rings so all is forgiven.

Why is that important? Well, if I say that “Han shot first,”9 I know that there is a percentage of people reading this book who will laugh or cheer. OK, maybe a small percentage will actually do that out loud, but the world is divided up into those who understand what I mean and those who don’t. The people who don’t have never seen the original Star Wars.10

Why does this matter? Well this is a clear way for particular Star Wars fans (like me) to self-identify using the particular shared moments of interest that only other like-minded fans understand. We talked about the importance of using rules to “belong” in Chapter 2. This is all tied up with that sense of secret knowledge that we share with other players. It’s not limited to games. This is also why we stand around the water cooler talking about the latest TV series or football game. This is part of our shared identity and it allows us to separate ourselves from those who “just don’t understand.” Personally, I enjoy watching football, but simply can’t be bothered to spend time learning all the intricate details and history of every game for all the teams. That leaves me outside the more mainstream conversations about sport. I’d personally rather spend that time trying to understand how and why games work better. I’m just that kind of geek.

Most people have their own “geek” areas that they love and want to spend more time indulging in. It might be music, history, even tinkering with model steam railways. Each of them has its own language and secret history shared only by the participants. This is the same instinct which Johan Huizinga’s described when he tried to define play in his Homo Ludus.11

Understanding Social Consequences

So with the “never seen Star Wars” model we need to look at different and competing factors within a game to understand the social implications of play. First, we want to understand who else cares about the game we are playing. If there are thousands or millions of other people playing this game every day what meaningful impact can that have on the way I’m playing the game? At the very least, does the presence of all those players allow us to reinforce for us that playing this game was a good idea and that spending money will be good value? More than this, as designers we need to consider how we instill meaning into those interactions. While we can enjoy a game on our own and find that deeply rewarding, a game matters to us most when we share that experience with others, particularly people we have a relationship with outside the game. We can of course also gain considerable pleasure from simply playing a game with another person who shares our values, or who at least is compatible with the way we play.

Meaningful Moments

Meaningful moments are about the stamp we make on the game, either for ourselves or for the other players we interact with. The more we can directly influence this behavior—such as the way we control a physics game or the soft-variables we exploit to complete the success criteria faster or with some alternative strategy—the more meaningful the interaction. We need to identify where these moments occur and think about how that can be shared and retain its meaning.

Introducing social aspects into play isn’t about blanket-bombing of Facebook walls as was once thought. Services such as Facebook, Twitter, Sina Weibo (China) and GREE (Japan) remain vitally important as a forum for communication and to find existing connections between players; indeed new services such as Kakao Talk (S. Korea), Line (Japan) continue to grow. However, they should be used carefully. Let us not forget that part of what makes a game playful is our ability to self-identify with a secret experience. We don’t want to share all aspects of our gameplay with everyone and when we do want to share, that post has to make sense and be meaningful to those people who don’t play. Everyplay from Applifier12 is a great example of a tool that can record your gameplay and that then shares that with your friends. When Rovio updated their Bad Piggies game with Everyplay this radically changed the emotional engagement with that game. For me at least it gave me a sense and purpose for playing with all the experimental pig-engineering projects and I found myself actively seeking out the Bad Piggies channels on the Everyplay site so I could watch the funniest clips.

I believe by considering what we mean by “never seen Star Wars” and applying that sense of shared experience to our games I believe we can find the meaningful moments of play in our game and find ways for players to share that with people who matter to them. This doesn’t just create a deeper bond in the mind of the player, it means that the recipients of their Facebook updates and Tweets have a vested interest in discovering what about your game matters to you. At this stage it’s not advertising, it’s a genuinely viral force for good and through the social sharing services this creates a natural form of advocacy, genuinely rooted in the playing experience. That trustworthy communication makes the people who receive the social game posts much more willing to accept that the player has a genuine love for the game and that itself is the most compelling reason for anyone to consider downloading your game.

The Columbo Twist

There is one last model I believe players should consider with engagement-led design (and we have yet to start considering the monetization process in earnest). And it comes from television rather than the movies. There was an American detective program that started 1968 starring Peter Falk called Columbo.13 In case you don’t know, the main character was an apparently bumbling detective in a shoddy old long coat; it was his task to work out who had committed the murder and to bring them to justice. The trouble with the format was that we already knew who did it! Every program opened up with all the circumstances of the murder quite obvious to us as viewers. There was no mystery! However, the show performed a magic trick on us all; instead of trying to work out who did it, the point was to watch how Columbo solved it. We saw him stumble his way through and wanted to shout at the screen that the murderer was behind Columbo, like some kind of pantomime. Then as the show came close to the end, as the detective was questioning the murderer for the second or third time, came the immortal words “Just one more thing …”

Just One More Thing …

That was the point where the show revealed that Columbo wasn’t an idiot unable to see the obvious in front of him. That’s when he revealed not only that he knew who the murderer was, but where the evidence was and, most importantly, why they had done it. You knew the twist was coming, it was a formula. You knew who the murderer was. But it was still a delightful moment, because you didn’t know why or how Columbo would solve it.

In terms of game design, this idea of looking at the satisfaction inherent in the final twist that concludes each episode of play is just as important. But the Columbo twist can help us to consider the longer lifecycle of the player too. What new extensions can we deliver to the story or the gameplay that makes us look at the playing experience in a different light? These processes are not for the initial product development phase—we will talk about minimum viable product delivery later in Chapter 12—however, it’s very useful to have at least thought about the potential scope for product extension early in the design. If there is no scope to extend the design or to accommodate some extension, perhaps even an ongoing release of content that will continue to delight your audience, then maybe your concept has a problem. If we can’t sustain our development over time we haven’t built a service, just a product. Our game will feel dead and quickly lose players. We need to find our equivalent of that Columbo twist to make sure that even the most familiar players still have an opportunity to be entranced by the game.

The Most Important Question: “So What?”

There is something else that the Engagement Led Design model can help us with. It forces us to ask a really important question, possibly the most important question of all: “so what?”

I can’t stress how important this question is for any designer to ask every time they write down a new idea, mechanic, plotline, etc. So what? Why should your player care about that?

We mustn’t forget that we are at the end of the day making a game for an audience and although I totally understand the desire to stay true to your art and personal vision (indeed I insist upon it), to do so without considering the effect of that idea, mechanic, or plotline on your player is folly.14 We are creating an experience that, unlike film or music, uniquely asks our audience to immerse themselves inside the world we have created. We need to understand, satisfy, even confound their expectations. However this only happens when we take the time to consider the consequences of our design choices and whether any player will care. We should always ask “so what?”

The Director’s Cut

This chapter has been about getting down and detailed with the way you think about the design of your game, particularly in the transition stages. The Bond opening is about looking differently at the transition between discovering and learning. Where the player has already made the decision to install the game, but where we know many simply don’t proceed. The Flash Gordon cliffhanger is about creating the conditions to support regular playing habits, especially as we move from learning to engaging. It reminds us that we have to build up the habitual lure of our game and to give reasons for players to return to that game. “Never seen Star Wars” asks us to think not only about why we “belong” with a specific game, but how social interactions influence our playing habits depending on our engagement, whether this is conscious or subconscious. Finally we come to the Columbo twist, which reminds us to ask that last question “so what?”. This question is vital to our ability to fairly review our designs as to ensure that we do our best by our players not just in the short term but throughout their lifecycle, allowing us to look for ways to extend the engaging life stage as long as possible before our players reach the churning stage.

These techniques are all focused around building deeper engagement and, importantly, trust between the game and the player. The value of that trust cannot be underestimated.

Notes

1 Personally I dislike the fact that game designers too often try to replicate the qualities of films in games. They are different media and offer different qualities of engagement. Books, music, film, and even TV formats all bring different constraints and opportunities and we should embrace their differences. However, I have found some of these film/TV narrative tropes to be useful tools to help explain some specific design concepts.

2 Time Entertainment did a list of the top 25 Bond openings in case you feel the need to check out some examples, http://entertainment.time.com/2012/11/09/every-james-bond-opening-scene-ranked.

3 I use the term “foreshadowing” a lot. It’s a term used a lot in narrative or theatrical writing. The idea is that we don’t tell the audience what is going to happen, but we set up the circumstances that means that they might work it out for themselves, or at least that they won’t be entirely surprised when a circumstance happens in the later part of the book or play. For example in a Bond movie we might see a character in the background observing Bond’s activity in a bar. This could easily be an extra just stealing the scene, however, when that character turns up later and is revealed to be Bond’s CIA contact we feel good as an audience—we noticed that character and just “knew” they would be important. My favourite way to define it is “pre-emptive hindsight.”

4 In December 2013 an update to Plants Vs Zombies 2 removed a number of core mechanics which simplified the progression mechanic but arguably limited the sense of personal choice.

5 Brian Lara Cricket was a classic hit for Codemasters on the Sega Megadrive in 1995, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brian_Lara_Cricket; very different from the original Tomb Raider heroine from Core Design and Eidos in 1996, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_Raider.

6 Every game designer can learn from the basics of marketing. Check out the Chartered Institute of Marketing (CIM) guide for some of the basic principles if you want to know a more, www.cim.co.uk/files/7ps.pdf.

7 If you want a list of some of the best cliffhangers from TV, this list might provide some inspiration, www.hollywood.com/news/tv/7808358/greatest-television-cliffhangers?page=all.

8 It was Kirsten apparently … http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Who_shot_J.R.%3F.

9 These Saturday serials generally had very low budgets and of course they were filmed at least 30 years before man landed on the moon. But I delight in them because they still have that sense of hope about science and space exploration.

10 If you expect me to explain this line then obviously you have never seen the original version of the Star Wars movie, only the special editions. You need to find yourself an older version of the film and watch it. Seriously! Put this book down now and watch it! Still here? Oh well … I never convinced my wife to watch it either.

11 As I have already said the special editions don’t count, not because they are intrinsically bad, just that there were editorial changes that profoundly changed the nature of the story, particularly for Han Solo … and I told you go watch the original movie … it’s worth it … honest.

12 Check out http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_Ludens_(book) for more information on that book.

13 OK, I know (at least at the time of writing) that I am the evangelist for Applifier, but this isn’t included as a sales pitch for that. I started working for Applifier as a consultant because I believe in this discovery and social sharing model.

14 Columbo is considered by some to be one of the best television programs ever made and takes a fascinating approach to mystery drama where we already know who did it, but we still want to see how he solves it, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbo.

15 The driving principle behind marketing is “to understand and satisfy consumer needs.” This might seem at odds with the creative drive to realise your vision, audience be damned. However, I believe that asking questions of our vision that relate to the satisfaction of the audience is extremely useful, especially if you want a commercial success as well as an artistic one. However, I don’t think we should ever sacrifice the vision to the mercy of the revenue. That way no one is satisfied.

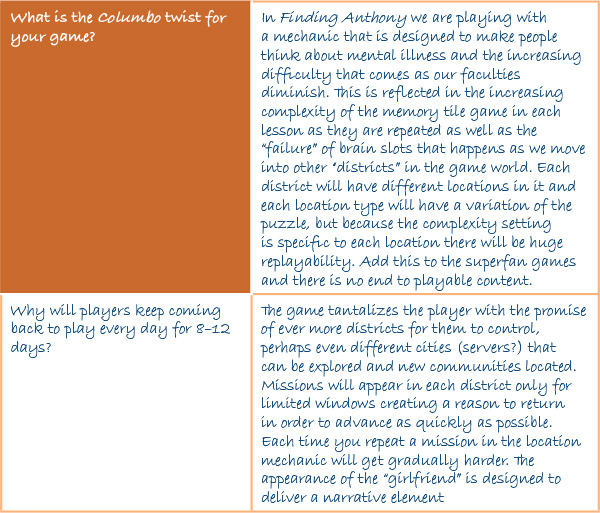

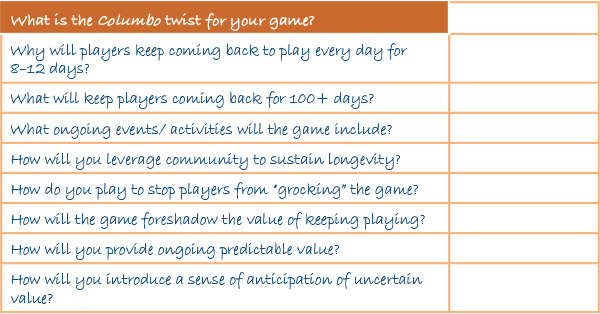

Exercise 9: What is Your Columbo Twist?

This is the last of the exercises from the themes of Chapter 9. In this section we ask “just one more thing” and look at our game from the perspective of the Columbo twist. This is about the character played by Peter Falk as the bumbling detective in the eponymous TV series, Columbo. We all knew how the murder was committed as we got to see it at the beginning of the program—including who did it. We then got to watch this ramshackle sleuth fumble his way through apparently failing to see what was obvious; until he said those immortal words, “just one more thing …” This is what we were waiting for. Now we would see why the crime had happened in the first place and, more importantly, how he had worked it out. We would realize the character’s genius and delight in the result. As a program format it should never have worked but remains, in my view, one of the finest detective programs of all time. The magic trick was creating a format that we felt comfortable with, that we could trust and that told us what was going to come, but yet still left us room to delight in the results. That’s a neat trick that you need to bring into you games if you want to sustain play for more than 100 days.

In this exercise we want you to think about what about your game will keep your audience coming back over the 8–12 days which is how long it takes for the people who will spend $100+ per month on your game to start spending at all. What will keep those players (as well as the freeloaders who we also need) to stay for 100+ days of play? Think about the ongoing events you plan to create that will create a sense of life for your game and can further build anticipation and ongoing excitement for the community as well as how they can create their own events/experiences. It’s also vital to think about how quickly players will take to perfect (or grock) the mechanic so it becomes second nature and how to avoid that becoming boring. Indeed how can we instill a sense in the mind of the player that the game always has new secrets to reveal only to the most dedicated players, foreshadowing ongoing value that is always yet to be revealed in full?

In essence this is about how we can sustain the level of interest as far and long as possible; evolving the experience along the way so the players feel there is scope to continue playing, perhaps through product extensions.

Worked Example: