Age of Digital Discovery

The digital distribution age we find ourselves in has created amazing opportunities for games studios to self-publish their content without needing the intervention of third-party publishers or wholesalers. Indeed, as I have often argued, Apple’s genius is the way it completely opened up the mobile market and set an incredible precedent for other platforms. However, this process has meant that there is no filter (for good or ill) over what content is available and indeed the fact that the market is so open has meant that by the time you read this there will probably be more than 1 million apps available on the app store.

The consequence is that we have a real problem getting our game discovered. Don’t get me wrong, this isn’t Apple’s fault or the fault of any of the other app stores. Their objective is for users to be able to find a game to play, not to find yours. They will promote content and that’s a vitally important channel. But you can’t rely on Apple to promote your game. Hope is not a strategy.

We Live in Interesting Times

The other problem is that this very age of digital distribution has also brought with it a revolution in marketing channels. Social media has changed the way we communicate with our potential players and this has affected the effectiveness of more traditional media. For example, TV and magazines simply don’t have the same level of audience they once had; by contrast games have become a highly effective medium for advertising, particularly for other games.

Traditionally, the game designer has had nothing to do with how the game is sold or marketed. We designed a game, helped make sure that the development team made what we had intended, and then passed our masterpiece over to those “awful marketing people who have no souls as far as games are concerned.”1 If the game made money it was because of our genius, if it didn’t it was because the marketers didn’t understand it. OK, that’s a terrible simplification, but we can’t work like that anymore. Since 2011 and the seismic shift Free2Play2 has now put the focus of monetization on the designer. More than that, increasingly the marketing of a game is dependent on the design and flow of the game to create moments worth sharing.3 Personally as a marketer and designer I believe this is just a reflection of our industry maturing and realizing what ever other industry has had to do, to become marketing-led.

Marketing 101

Having a marketing-led business essentially means that you need to have a focus on your customers. Indeed I was always taught that the very definition of marketing was the identification and satisfaction of consumer needs. Marketing is not about fancy adverts and expensive parties, although there might sometimes be good reasons for both. There are some more fundamental principles at work and I strongly believe these can help us with our design process and help us to build discovery through the game itself.

This all starts with the 4 Ps;4 four simple words that help us think about what we are making and why, as well as how much we will charge, who our audience is, where they can be found, and how we are going to talk to them.

The first P is product and there are several questions we have to ask ourselves when considering our product (in this case service also applies). What are we making? How will it be used? What does it look like? How do I consume it? And so on. It’s important to fully understand what it is we are selling and what it is we are using to attract and retain our audience. We also have to consider the market context for our game including the competing forces5 that affect its reception by players. The list doesn’t stop there, we also have to understand the costs of production and distribution. Marketing-led products aren’t just looking to sell as many units as possible; they seek to find the optimum balance between costs of production, price, and volume of customers. We have already talked about how important a repeat customer is in Chapter 4, and this becomes critical for a marketing-led business if we are to create a reliable and sustainable income stream over time.

The Fifth P

All important stuff, however, I must admit to a personal twist on the traditional approach. I believe that products are really about people (the fifth P, if you like). If you reduce all of the decisions and creativity we need to deliver a great product it comes down to understanding people. Obviously we have to first consider the customer or player of our game. This audience used to be as simple as “someone like us to plays our games.” When we believe our customers are like us it makes a lot of things easier. We already instinctively understand their motivations and likes (they are like us after all). Unfortunately, this has never really been true. Even among the hardcore games audience there are variations in terms of reward behaviors as we talked about in Chapter 2, when we briefly outlined Richard Bartles’ “player types.” The other reality is that by building games we want to play, we have been self-selecting an audience who would be interested in the same things that we are. We have not been trying to create experiences that other people might play, because we believe that they “didn’t buy games.” Social and mobile games have shown that to be a lie. OK, maybe that is a little too strong, but it is clear that there is now a bigger audience and they are not all just like me. Accepting this means that we have to spend more time looking at the different drives and interests of each player. But with games like Subway Surfers gaining 26 million daily users and Candy Crush getting over 70 million, it’s not possible to understand every view or need of every player. So instead we have to find some way to generalize by differentiating or segmenting players into coherent types.

Who Are Our Players?

There are many approaches to how to do this. The first and most common method is demographics. Here we attempt to identify the age, sex, and location of each player, perhaps also their cultural or occupational context. However, these attributes are both very difficult to verify and increasingly are not proving to be particularly useful. Assuming someone will behave in a particular way because of their age or location is not very sound. A much better way is to look at how people actually act. This is something we can do really accurately in online game services but it does take time and lots of AB testing6 to understand the types of average behavior. There are some variables we can know, such as how often they play, how successful they are with the game, how much they spend, what virtual goods they buy, how often they interact socially in the game, or how often they share material through the social graphs. Of course this doesn’t tell us what why people don’t do certain things or how many people might have played if you had changed something about the game. There are some high-level segmentation models we often fall back into with F2P and they are the whale, dolphin, minnow7 and the freeloader (non-payer). I find that approach unsatisfying. It assumes that the objective is just how much money you spend rather than what motivates you to play. I prefer to consider factors that are likely to affect adoption, retention and monetization. However, how do we identify players who have qualities that can help us improve performance in all three metrics?

Figure 10.1 What highly influenced your last five downloads?

Stop Hunting Whales

In February 2013 Applifier conducted a user survey, asking what influenced players’ decisions to download their last game. This showed that the principle influence the participants reported was “word of mouth and social media” at 37.2 percent. This included personal recommendations from friends in person or via some social media, including videos of play. You’ll notice that this is slightly greater than the impact of the app store itself, including features as well as the search process. The role of advertising was reported as only influential in 12.4 percent of the responses. There is room for bias here.8 Users are notoriously reticent to accept the influence of advertising and in these responses most players declared multiple influences.

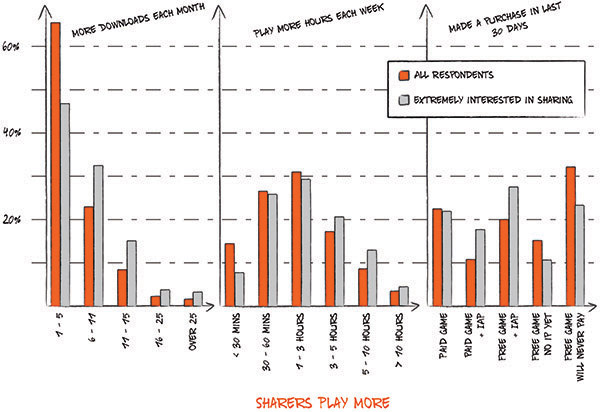

Sharers Stay, Share and Spend

Social factors turn out to be more influential than even this result shows us. We discovered that 20 percent of the respondents self-identified as a segment group we called the “sharers.” It turned out that this segment downloaded more games, spent more and played more than other players.

What is also interesting is that the playing behavior of “sharers” tends to reflect a better balance of interests than the “whale” players. This can be extremely valuable as it means their interests provide a better perspective of overall playing interest, which creates the conditions to allow whale users to bubble up. While it’s very hard to generalize across different games, it seems that the highest spending users appear only when there is a strong pool of other “engaged” players.

Figure 10.2 Sharers play more.

All We Need Is Love

Of course don’t take my word for this, find out for yourself and check with the data you can obtain and confirm how universally this applies to your game by asking your players and checking the accuracy of their responses by looking at their actual behavior. The key thing we want to learn is what will make people care about our game enough to play regularly and even pay, but we want this information broken down into each of our segments. A lot of this comes down to how much they trust you and how you show them in the game that you love them back.9

Heaven and Hell Are Other People

Potential players are not the only people that we have to consider. Think about the people in our team who are making the product, as well as the partners or colleagues involved at every stage of the project. If our team doesn’t fully buy into the product we are making then there is no way we can deliver the right product (or service). Understanding how those people work at their best is just as important if we are going to make our game experience as efficient as possible, and I suggest that this shines through in the end experience itself.

If we understand the people elements of our game, this will vastly help to make sure we have the right product. Then we can start looking at the other 3 Ps.

Putting a Price On Success

The second P is price. There are many different pricing strategies, each of which applies to different games in different ways. Premium pricing is used to refer to games that are charged upfront, rather than necessarily being a measure of quality of experience. Paymium takes such a paid game and includes additional material within the game for players to buy. Freemium removes the initial pay-way presented with a premium game and concentrates on the in-app revenue opportunities including virtual goods and advertising while ad-funded games rely only on advertising revenues. We will talk about monetization strategies in detail in Chapter 13, but when we want to create a game as a service the answer is usually freemium. We have so much to gain if we have the mindset that makes it free to access our service and create a market of goods within our games that continue to add value over the complete user lifetime. However, making this realty is not easy of course. The trick comes down to working out what we are actually selling and what we are using to attract and retain an audience. With Free2Play we aren’t selling the core gameplay anymore, that’s what we use to attract our audience and to try to retain them. Instead we look to added-value services to deliver us some income.

Kids and Credit Cards

Considering price is more than just the business model. We also have to look at how easy it is for our players to pay for goods and how much they understand the value of what we have to offer with our added services. Most payment services rely on credit cards but what about people who don’t have them? Credit cards are not used significantly in China or Germany for example. Can we find other methods, perhaps operator billing, cash-cards or similar services? Where we have a child audience this is particularly important as we need to ensure that players can’t accidently make purchases and to engage with the parents who will act as gateway to any purchase.

The damage that can occur to your brand and just as importantly the trust between you and your players if this goes wrong can be considerable. To avoid this, it’s worth going the extra mile to make sure that the process feels fair and deliberate. That might lose you a few sales in the short term, but this pays dividends in the longer term as long as your players feel they can trust you.

Location, Location, Location

The penultimate P is place. However, this isn’t just about the physical place; in our digital age the nature of place has changed somewhat. Instead it’s about understanding where your players’ attention is rather than the traditional ideas of retail and logistical distribution.

For games we have an ever-increasing range of devices to target—and I don’t mean the operating systems or OEM platforms. There are more important questions such as what form-factor of device you are targeting; is the game played on a phone, tablet, “phablet,” console, smartTV, or all of the above? What about “smart” glasses or watches? Will there be a constant internet connection? How much local storage will there be and will the users be restricted in the volume of data traffic available to them? All these are practical considerations not just because they affect the product design, but because they present different delivery challenges.

As well as the practical limitations of the device come the situational issues that players might face and that are likely to affect their playing mood and mode as we discussed in Chapter 5. Place can affect the available choices, for example, playing a hardcore dedicated session requires us to settle into a defined space for a long duration. Alternatively, a casual “dip-in-and-out” collection of short bursts of play to pass the time. This behavior is often linked to the situation the player is in; such as on the commute, at school or work, waiting for a bus, or sat next to their family while they are enjoying their favorite TV program.

A Place to Talk

The more traditional way to look at place relates to where the potential player will seek out information about games and how you find the best opportunities to communicate with them. We have some amazing techniques in the games industry that give us greater access to customers than most industries. First, we know that players are often using their phone to play other games. This led to the rapid growth of cross-platform networks like Applifier on Facebook and Chartboost on mobile; these allow games to swap installs with each other. Most other industries don’t have this kind of direct communication channel. It’s no surprise that we saw the cost of acquisition on Facebook and mobile skyrocket in 2010–2011, with players like Zynga and GREE allegedly spending more than anyone else on in-game adverts.10

Acquisition will probably continue to get more expensive, especially as we have better mediation services targeted to support big brand media buyers as they start to take mobile seriously. Some games now command larger audiences than most TV shows and this will in time lead to greater demand. My guess is that we might just look back to this time and think that these record-breaking prices were in fact quite cheap.

Any Other Place

Other games are not the only place we can communicate. They just happen to be particularly direct and useful forms of access, which also means that there is lots of competition for them. We can’t ignore other places where players congregate when they are not playing. We can look for correlations between playing behavior and other measurable (or at least researchable) factors and find correlations between, for example, whether they shop at a particular brand of supermarket or what specialist magazines they might subscribe to, or even which TV services they use.

Clear Communication

This takes us neatly to the last of the Ps, promotion. We know what our product/service is, whose needs it is designed to satisfy, what price it will command, and where we can communicate with that audience. Now we have to make sure we get across the right messages. As we discussed above, advertising is the thing most people think they understand. It seems pretty simple, we put out an advert of our game and we see a percentage of players click through. Better yet we can know which advert link triggered the download and use that to track value from that source. Added to that we can buy on a cost per acquisition basis so surely we have no risk, paying only for the number of installs. We can even AB test11 different marketing approaches down to a very fine level knowing whether a green or red call-to-action button works best. This kind of precision marketing helps us to make better campaigns but it can’t make a bad game any better. It can also fool us into thinking that we are being efficient.

The very fact that advertising is measurable means that we become biased to its influence. After all, we can’t measure the benefits of PR or other indirect communications. These activities don’t change behavior in a measurable way, but does that mean that they are a waste of time? There are influential industry leaders who claim that marketing, in particular PR,12 doesn’t work. However, we should consider those games that have become runaway successes without “any marketing activity.” These games usually have a number of things in common, including an intrinsically compelling experience and that they cause some kind of “trouble.” This particular combination has the effect that those people who play them want to show off the game to others or to write about them in the press. They might even, if they are lucky, catch the eye of the app stores and get the hallowed feature slot.

Create a Context

Remember our earlier survey of influences; 37.2 percent were highly influenced by word of mouth or social media; with 15.3 percent influenced by other media including web, print, and YouTube; slightly greater than the 12.4 percent from advertising. Importantly, as most of the respondents quoted multiple sources of influence, I suggest we can’t afford to ignore any appropriate channels or forms of communication if we want the best chance to get the largest audience.

There is an old joke about marketing which says “I know that 50 percent of my budget is wasted … I just don’t know which 50 percent.” This kind of thinking is simply wrong. Marketing is not sales. Sales is about creating a funnel of potential clients, focusing on those that you can close and then closing them. Marketing is about creating the widest possible reach as well as a positive context where players become more likely to choose to get our game.

Immediate, Relevant and Gorgeous

Communicating with your players throughout their lifecycle is critical and the more we do this in person the better. We have already talked a little about the kinds of things that are important at the early stages of discovery, the first pattern we talked about in Chapter 5, which starts with the name of the game and the icon. When thinking about communication however, we can go further and look for the intrinsic qualities of our game and use that as the foundation for how we communicate with the player. During my time at 3UK we used a system to gauge the potential of any game based on three parameters. Was the experience (art & game) “immediate,” “relevant” or “gorgeous?” “Immediate” asks us to consider how quickly the game concept will be understood from the combination of its name, icon, and—if necessary—a screen grab and description. “Relevant” is more about the internal consistency of the game but also how this consistency is applicable not only to the player, but also of any associated brand. The classic example where this went wrong was the RiotE game Lord of the Rings Bowling. Not only a terrible idea, but completely irrelevant to the brand’s fan base. Finally, we should consider “gorgeous.” This is a trickier thing to describe. It’s not just about artistic beauty. Simplicity, cuteness and irreverence can all be gorgeous in their way. However, I’ve often been struck that, while it’s often nearly impossible to say why something is gorgeous, deciding which of two ideas is most gorgeous seems pretty straightforward and surprisingly consistent among audiences.

Getting and Keeping Attention

Once we get past the intrinsic qualities of the game we should start to consider how we communicate to players within the game and how they interact with each other. As we have said, social elements and sharing are important factors. Think about what tools are available to both us and them to communicate with each other. How will this be administered and moderated, and how do you avoid damaging misuse? How often do you make updates? A regular, even predictable frequency of message or update can be extremely useful, but make sure it’s relevant to their needs and don’t be too predictable as important information might become overlooked.

Who Are We Talking To?

We also should consider a wider audience than our players themselves. Who are the “publics” we want to talk to and what messages are we trying to communicate? This is more than just to create awareness among potential players, it’s also about making sure that we understand the shadow our game casts on those others who may never play. What impact will their opinion have on the people we hope to convert? If we send out blanket Facebook spam, is there any wonder that the non-player audience might start to get angry about this? Isn’t it obvious that this will put many potential players off from converting to play? That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t use Facebook to communicate. Instead it means we have to ensure that these messages are valued even by the never-playing audience, or that what scorn we create does so in a way which motivates players to more deeply engage with the game. That’s not an easy trick to pull off deliberately but I would suggest that the more negative behavior possible inside games such the Grand Theft Auto series created a response that built the game’s reputation.

Magical Moments

The key for me is to find messages that ring true about the nature of the game concept and are fully realized inside the game-playing moments. These we need to create magical moments of delight that feel personal and unique to our players and that they actively want to share and give them the mechanisms to do so. Gameplay recording services like Everyplay from Applifier do exactly that by sharing video created by the players who want to show off what they are passionate about. This is a perfect way to encourages potential players to become excited about what the game represents and allows non-players to accept those messages as genuine expressions of delight.

Don’t Hold the Press

Another key public is of course the press and other media. Bloggers and journalists need to feel valued and have the chance to say something unique about your game, something that will give their readership a reason to choose their articles. Managing your relationship with professional journalists is a very different thing to working with bloggers. There is an expectation of more thorough analysis of the content, although that is not always the case. Nurture the journalists who care about their work and who don’t just push out the latest press release. They almost always carry more weight with their audience and will usually hang around in the industry longer. But be wary. They are always looking for a good story and may take a particular spin that wrongly represents your position. This can be negative, even damaging to your brand, game or company. You have to accept that their job is to write interesting articles for their audience, not to sell your game. And you have to accept that not all journalists are to be trusted. However, the best of them will respond if you correct them, perhaps by covering some new story or angle. The adage that there is no such thing as bad press isn’t quite true, but Oscar Wilde was right that there is only one thing worse than being talked about and that’s not being talked about. With bloggers, the motivation is more personal and often unique to each individual. It takes a lot of unpaid effort to build and then maintain a popular blog and that dedication requires a special type of person. Getting these people on side means we have to think about what their position or attitudes to the industry are about and how we respond to those interests. Bloggers usually respond very well to you giving them attention and especially if you take an interest in their motivations. If you look after them you can create a fanatical voice working for you, but it’s hard to sustain that kind of relationship with large numbers of bloggers; just like journalists they want a scoop.

Getting Featured

If we want to gain a feature position on the app store we have to pay attention to the platform holder. I don’t just mean Apple or Google Play here, think about PlayStation Network, Xbox Live, Steam, etc., even Facebook! In some territories such as South America or South Korea, the mobile operator still has a major influence. We need to give them a reason to give us the time of day. Already having an audience helps, but even when we are building that up we should try to pay attention to what that platform is currently focused on. Are there new hardware or OS changes that we support in our game that helps them in their needs? Choosing to exclusively release an update on a single platform can help get attention; perhaps even an advance, provided the opportunity is significant enough to get on the platform management’s radar. As with all promotion we have to understand why they should care and communicate that to them.

Interestingly, the extent to which your game is localized into different languages, perhaps even culturalized,13 the more scope you will have not only with the potential audience but also with the platform holders.

Thinking Professional

There may be many other “publics” you should pay attention to including investors, publishers or trade bodies. There may be other channels to consider—from outdoor posters to a promotion in a chain of cosmetic stores that happens to be the most popular with your players. If you want to deliver discovery you need to find an efficient way to use these routes to market and make sure that the “publics” have not only a reason to care but a method by which they can take action, ideally one where you can measure the success as readily as precision advertising.

What’s the Point?

Delivering discovery starts within the game itself. It comes from understanding the values you want to communicate and the various different audiences you need to communicate to. You can’t expect to be successful if you don’t find the right balance of budget, effort and brand values that attract an audience.

Designers need to spend time thinking about the core marketing concepts presented here if they want a fighting chance to find other players who are willing to part with their hard-earned cash. Building a game for yourself is a hobby; building a game as a service requires that we consider our wider audience and how we can satisfy their needs.

Notes

1 OK, this isn’t a real quote but does reasonably sum up a lot of the reactions I have witnessed by developers or producers about marketing people. They were rarely flattering. To be frank, a lot of marketing people had similarly unflattering opinions about the business sense of the development teams, and not always without reason. I’ve always sat somewhere between the two camps and tried to stay out of it as much as possible.

2 In the first six months of 2011 according to the Flurry Blog, the mobile games market went from 39 percent Free2Play to 65 percent. I think that counts as a pretty seismic shift in business model, http://blog.flurry.com/?month=7&year=2011.

3 I would generally argue that marketing has always been dependant on those magical moments of play, but in the era of box retail products it was possible to hide a number of sins with a good advertising campaign. However, there is a limit to how much you can put shine on a terrible game or even one that just misses the mark regarding the audience needs.

4 Technically the original 4 Ps have now been increased to seven; although there are contenders for 12 Ps, which are essentially providing more detail on each of the original four. For our discussion here we will stick to the classics.

5 In 1979 Michael E. Porter wrote How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy about how suppliers, customers, new entrants, substitutes, and competition affect any business.

6 We will talk a lot more about AB testing in Chapter 11.

7 I understand the term “dolphin” was coined by Nicholas Lovell on his blog, www.gamesbrief.com.

8 We will talk about collecting data in Chapter 11.

9 This may sound a little strong, however, I’m serious. You need to pay a kind of loving attention to your product and its consumers; if you have no love for either then this will show through in the end.

10 I once got into trouble for saying this on a panel. I suggested that mobile advertising was becoming too expensive for many developers because Zynga and GREE were outspending everyone else. I honestly don’t know how much they spent, however there was good anecdotal evidence that it was considerable.

11 In case you don’t know, AB testing is a form of analysis where you present different options (game/advert/etc.) to a user and can see how subtle changes can increase usage. We will talk about it in Chapter 11.

12 Torsten Reil of Natural Motion said this at Games Horizon in 2012, a sentiment he repeated in an article on GamesIndustry.Biz, www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2012-06-27-mobile-games-marketing-doesnt-work-at-all-reil.

13 It’s important to consider cultural influences as well as language changes. For example, you can’t default to underwear for female avatars in the Middle East and a game with skeletons in China can be poorly received. For more on this, check out my article on the topic on PocketGamer, www.pocketgamer.biz/r/PG.Biz/Applifier+news/feature.asp?c=53647.

Exercise 10: What Makes Your Game Social?

In this exercise we are going to look at the social aspects of your game. Not every game need have a social factor; however, there are some correlations between social factors and the proportion of users who spend money in the game. We need to consider what we discussed in Chapter 10 and how the different social levels impact our game design and the interactions between our players.

The objective here is to avoid simply jumping to a decision to blindly add social tools without considering the social meaning of each element. There is no point putting items in just because we have seen them in other games. We have to consider each in terms of their impact and effort to sustain, potential versus realistic return and the opportunity cost of other things we might be doing in our lives.

Key to your thinking through this exercise is the recognition of the need to set positive expectations that exceed the effort required to sustain the social interaction. There will always be external social pulls, however, you should think about how to sustain positive associations for connecting with others within this game. Thinking this way allows us to realize that social features require effort and can create stress among some players who can be fearful of a degree of humiliation, while others will see games as an opportunity to display their prowess.

Think about how you will introduce social elements in the context of trust, where players see the value of opening up their friendship profiles to the game, as opposed to the risk of exposing those friends to impersonal and unwanted spam. How you use this data should be trustworthy and honest and there is no better way than to use the tools as they were intended, i.e., to allow the player to express themselves. If this happens to be about their experience of your game then great; if the way they express this is unique to their performance or creativity while playing, all the better.

Once we have established the social context, will you expand on that with other social concepts? Will there be asynchronous or real-time play and how does this fit with the superfan game?

Worked Example: