First Principles

Whatever you think about mobile or console games, I’m hoping that if you have picked up this book that there is something about the game design process that delights you. It’s more than just the pleasure of playing a well-crafted game (regardless of the platform). Game design combines an intellectual and creative challenge to manifest your ideas into something others can play through and want to pay you for the privilege of playing. We want players to be charmed, empowered, surprised, even scared. But unlike other art forms we want players to resolve the experience for themselves; to make their own game. People have been creating and playing games for centuries before the introduction of personal computers, consoles and mobile devices. However, since the 1980s, computer games have largely driven innovation and creative design for games, although arguably not always in the gameplay design itself.

Making a Stand

In this book I’m going to assume you have some idea about what makes a good game, and ideally that you have a little experience making games. Don’t worry if you don’t. I also plan to provide notes to suggest good sources of inspiration and insight. The purpose of this book is to provide a framework to make it easier for you to make games as services. This will take us back to some of the basics of game design to find lessons that lie at the core of every online, console, or mobile game; perhaps even elements that date back to old-school tabletop board games, card games, and maybe even role-playing games. I also want to show how these lessons can help us rethink the way we approach both the artistic and commercial elements to help you make the best possible games suitable for this era of always connected devices. The technical power and ability to leverage online services has so rapidly filtered into every home and every pocket with laptops, tablets, consoles, and—of course—the cell phone almost all of us now carry. The trouble is that we are still in the midst of this massive change and at the time of writing some of the biggest changes seem to be just over the horizon. So to avoid this book becoming out of date before it’s released, I have tried to focus on the deeper, lasting principles that matter to making games as services, rather than the particular trends currently popular. My plan is to then continue to add to this material using the companion website www.GamesAsAService.net; a site that I hope will become a place for designers to share ideas and learn from each other.

Service with a Smile

We are seeing the way we consume and experience games change faster than ever before and at the same time we are seeing this great entertainment medium at last reaching true mass-market audiences, something thought nearly impossible only ten years ago. In particular we are seeing a dramatic rise of ‘games as a service’ and of course the “freemium” business model, both of which I will argue go hand-in-hand. I believe this will be a driver for greater creativity, allowing us to make better games, not just more profitable ones. I will try to show why we can no longer afford to simply build a game, throw it over to the marketing team or publisher, and then hope that someone buys it. Hope is not a strategy.

In particular the old approach of creating retail ‘box-products’ is not just inefficient but dangerous, perhaps even suicidal, for game developers—and not just for mobile and tablet games. We need to rethink our approach to development and instead look at the way players now consume their content and use that to build games as services instead.

First Bite of the Apple

The tipping point that brought us this change, for me, was the arrival of the iPhone. However, unlike many people, I believe that it is wrong to think of this first iOS device as an extraordinary technical achievement. At the time it was released, most handset manufacturers had devices that were—at least in part—technically superior to the first iPhone. Let’s not forget that the most basic phone-call features of the first iPhone were pretty terrible. However, Apple’s little device showed us what was possible when you make the user experience seamless.

Many will argue that it was the simplicity. I’m not convinced by this argument, but this isn’t a book about user interface design so I won’t bore you with the details of that discussion. However, what I do think is relevant to this book is that, unlike all other handset devices at the time, the iPhone experience was both internally consistent and joyful to use. For me the genius of Apple at this time was making the mental shift towards delighting the end-user not just pushing the technical aspirations of the manufacturers. But even with this, the first iPhone doesn’t count in my mind. The really important stuff came in with the iPhone 3G and an almost incidental release Apple made the same day. On June 9, 2008, Apple launched the iPhone 3G and with it the new App Store,1 which it described as:

providing iPhone users with native applications in a variety of categories including games, business, news, sports, health, reference and travel. The App Store on iPhone works over cellular networks and Wi-Fi, which means it is accessible from just about anywhere, so you can purchase and download applications wirelessly and start using them instantly. Some applications are even free and the App Store notifies you when application updates are available. The App Store will be available in 62 countries at launch.

That’s it. That’s how the biggest innovation in application retail was introduced. In hindsight this might seem an inauspicious start, but we must remember that the original iPhone release didn’t even mention downloadable apps2 in fact instead they talked about using Web 2.0 techniques to support third-party apps.3

There is no doubting that the Apple team did something amazing, even if I don’t believe it was deliberate. They opened access to everyone to release any app. It was (and largely still is) possible to get through the approval cycle within just a couple of weeks. You don’t have to convince anyone of the merits of the app you want to release. You just have to meet Apple’s documented rules. This has removed nearly all of the barriers to entry for developers of any size. It turned out to be a completely disruptive act and continues to have a profound impact on everything we do in games. They opened up the floodgates for new content and had immediately leveled the playing field so anyone could publish a game and access an audience of millions of users.

Supply and Demand Matters

Of course that has now led to an unprecedented volume of games and apps, and because the pricing was set by the developers themselves there was an inevitable consequence. The average price for a game went down.

This is a normal economics principle. The price we are willing to pay for any good, especially a luxury like a game, is determined by the supply of that item and its demand. If supply increases and demand remains unchanged then the price will inevitably fall. On June 10, 2013, Tim Cook announced that the App Store was now hosting more than 900,000 apps;4 but by the time of publication, I suspect we will be close to the 1 million mark. There are now more good games on the store that I could possibly play in my lifetime. This effectively infinite supply of content inevitably means that the “natural” price for a game will be nothing; free.

Not the only Game in Town

The emergence of Apple’s little device was not the first or only place where innovation for games pricing has happened. In 2003 we pioneered an early form of mobile in-App purchases at 3UK with the introduction of a “rent” game. It was too early and flawed, but the technical innovation was to allow a user to make a purchase within an app. Also in 2008 Sony introduced PlayStation Home as a Free2Play (F2P) experience for owners of the console. However, the first steps for F2P largely came out of the Massively Multiplayer Online (MMO) world, especially those wanting to target a younger audience—in particular online services such as Neopets (1999). Other MMOs followed suit, such as UK-based RuneScape (2001)5—still recognized as the world’s largest MMO6—and Korean-based Maple Story (2003). Maple Story and Neopets both involved the purchase of virtual goods within the game, but RuneScape initially only offered a subscription service for paying players.

Online browser-based games continued to innovate including notably Big Point’s Dark Orbit and the sale of their Droid X. This was a virtual good that, on paper, costs $1,000 of their virtual currency; however, when you look under the surface this tenth droid required that the player had all of the previous nine and only cost the full amount if you decided to buy it outright and hadn’t earned enough virtual currency already.7 How much money was actually spend on them is unclear, but the value was clearly set in the minds of the players who owned them.

The Only Certainty is Change

More change and more innovation is coming. The arrival in 2013 of the microconsole heralds another era of change and new device opportunities for developers but, at the time of writing, it seems unlikely that many of the first wave of these smaller, cheaper, open access options are quite right to take over the imagination of all players just yet.

Then of course in the same year we have seen the arrival of the next-generation Xbox One and PS4, both of which had a few missteps in their initial launch PR. However these are both likely to embrace greater flexibility in pricing and retail models and, hopefully, a deeper engagement by the prestige side of the industry with the world of indie development.

Change continues to come at us in many forms and on many devices. I may occasionally focus on the iOS platform as an example, but only as the place where the Darwinian forces are perhaps strongest, where competition is fiercest, and only the fittest will survive.

Whether or not you agree that iPhone’s arrival has, as promised, changed everything, the fact remains that everything has changed and the iOS market provides useful information to allow us to gauge that change. Further than that, I believe that change is only really starting. I believe that increasingly, rather than focusing on one device, we need to consider the opportunities and consequences of gameplay on all the available devices of all kinds of color, flavor, shapes, and capabilities. What they will have in common is that we will want to play games on all of them at different times and they will all be connected to the internet. What an amazing time to be in our industry.

No Such Thing as a Free Lunch

Looking at the iOS and Android markets its clear that F2P has become the dominant business model in the mobile market, displacing all but a small number of premium games from the top grossing charts. This transition had happened by June 2011,8 and has continued to increase its hold over revenue.

In this book we will consider why this is and why, from a psychology perspective and a market perspective, there is a tremendous natural advantage in not charging for your game upfront. Indeed I will argue that we can create more anticipation of value inside our games by doing what games are best at—building engagement. There is then no surprise that when we show our players what they love and offer them different ways to invest in our games, they will spend more.

Free is Only Part of the Story

Going “free” is not just about removing the barriers to players trying out our service. With a freemium game we are no longer selling the gameplay itself, or even the reasons to return to the game. We have to focus on selling things that players want to help improve their playing experience. It doesn’t matter whether that is an avatar outfit, a companion in the game, an energy crystal, or a farm building. If a player loves your game and you offer them something that helps them enjoy it more, then they will be willing to pay. But, this only really works if you think of the game you build as a service and continue to invest in the experience, showing you love your game too.

I believe that this requires a complete change in the way we look at game design, playing mechanics, and even production processes. It requires a commitment long after the release of the game to sustain it with new content, events and features. It is a commitment between the developer and the player that shouldn’t be started lightly. Indeed typically you should expect 80 percent of the development costs to happen after your initial release.

But There is a Problem …

Of course there is a problem here.

A lot of people, especially game designers, don’t like the way many freemium games work. Indeed they don’t even like the words we use to describe them. How can a game be F2P if you are being constantly asked to spend money? Does “premium” mean you pay for it or just that it is of a higher quality? There have even been investigations, such as by the UK Office of Fair Trade, into the practices of selling in-game assets to children.

Then on the freemium side you have similarly daft people saying that “developers who make Premium games are Zombies. The living dead. Dead, but they just don’t know it yet.”9 There have been devastating predictions about the end of premium games as we know it or at least a reduction to “No more than 12 games a year.”10

So I started to wonder. Was there a way we could find some common ground, a way to look at the market objectively?

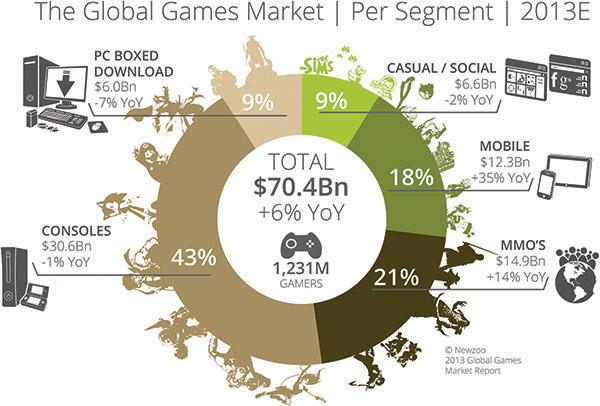

Games Market Research Company Newzoo showed the status of the games industry in 2013 by comparing the different platforms;11 which largely reflects an ongoing position following the past couple of years. Console remain (for now) the largest sector in terms of revenue. However, this has been in decline for some time as we have waited for the next generation to arrive. This decline has been particularly damaging for the console-based studios, which have seen dreadful losses as large, historic studios have gone under. Sony Liverpool Studio and Real-Time Worlds were both notable examples of large scale losses in the UK. However, many of these redundancies have sparked the creation of new independent studios usually focused on mobile games. Studios like Hutch Games exemplify the transfer of talent from the console space into the independent mobile and tablet sector; a sector growing at 35 percent year on year.

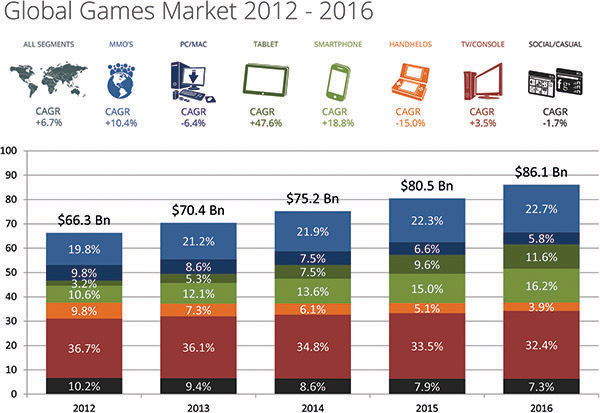

This growth is expected to continue with Mobile and Tablet leading the charge.12

Figure 1.1 The global games market, per segment, 2013. © Newzoo 2013.

Figure 1.2 Global games market 2012–2016. © Newzoo 2013.

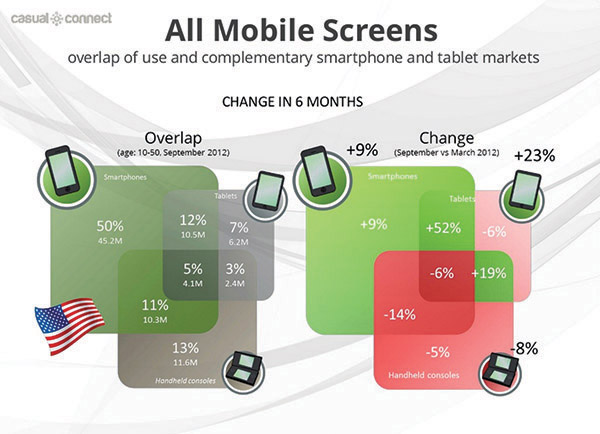

However, what’s most interesting is the rapid change in the use of multiple devices. We have been using different devices for quite some time but until relatively recently few players would transition from a game on their phone and pick it up on their laptop, usually preferring one device for specific activities. That appears to have gone and we are increasingly regarding applications as things that should work everywhere, choosing the device that best supports our current circumstances, a “mode of use” if you like.

Figure 1.3 shows the overlapping use of devices and how that changed between March and September 2012, a trend which has continued ever since.

There is clearly a change that has happened. Mobile has manifested this change in the most profound way with games delivering 33 percent of the downloads and 66 percent of the revenue on iOS App Store in 2012. However, we have also seen various experiments for downloadable content (DLC) being made by the traditional console game publishers to augment their retail box-product sales; even with “Season Passes” being sold to mitigate against the rising secondary market of pre-owned games. However, the more profound impact on console has been the introduction of Xbox LiveArcade and PlayStation Home; both surprisingly successful in their ways. There is no reason to expect consoles will be immune to the F2P model.

Figure 1.3 Overlap of use and complementary smartphone and tablet markets. © Newzoo 2013.

A Religious War

Of course even with objective data I won’t stop people arguing the relative merits of premium and freemium as the debate has polarized into an unhelpful, almost religious, bickering.

Perhaps there is something more fundamental at work? Perhaps we are looking at the symptom rather than its cause? If I am right then we have used the wrong emphasis by focusing on the money. I think this preoccupation with revenue has hidden a more important change—the move to games as services.

Let us take a step back from the arguments about F2P. There has been a decline in old-school physical retail models and there has been a rapid rise in digital content, not just for games. Freemium models have attracted not only large audiences, but also greater revenues than premium games on mobile and table. Social media and internet access on multiple devices has become ubiquitous and has affected the way traditional mainstream retail brands talk to us. Look at the high-street of your local city. Everything has changed. So, of course, the way we buy games has changed too.

(Not) the End of Premium

Don’t get me wrong I don’t want to lose the excitement I get with those amazing of AAA13 console titles that continue to attract hugely dedicated audiences and of course make vast amounts of money, but it’s a blockbuster, “hit or miss” model. These games have to make huge sums to offset the huge risks and the ever-bloating costs and resources needed to build the next seminal title. The coming generations of consoles with the power to create photo-realistic real-time generated avatars make it unlikely we will see art production costs go down anytime soon.

I’m also not saying that every game has to be freemium moving forward. Sometimes the flow of the game you want to create won’t support a virtual goods or advertising-based business model; however, as this book will explain, that will be the exception rather than the rule and will always compromise the potential audience size and revenue.

These AAA projects typically require multimillion dollar budgets and teams of more than 100 people engaged for three to four years. That’s a lot of risk to manage and inevitably creative freedom will be inhibited to some extent, so is it any surprise that we see increasingly fewer AAA games released with an increasingly smaller range of game formulas? Indeed I believe that it is no surprise that many otherwise promising projects are getting cancelled in increasing numbers before we see so much as a trailer.

It All Started With the MMO

The MMO market has faced similar problems. The subscription model has been an amazing ongoing revenue source for these games, but in the last few years, that model has started to break down with many closing down or migrating to a F2P model. Too often this has been a poorly implemented change as well. At their peak, these games showed us just how committed a small niche audience could be and wooed them into buying ongoing subscriptions on top of the original purchase price. World Of Warcraft reportedly had over 12 million monthly subscribers at its peak in 2010, but by July 2013 this had dropped to 7.7 million, a loss of 600,000 in just three months and the lowest point since the first expansion, leading to announcements that they were considering a F2P in future. Lots of MMOs launched in recent years have fallen foul of this transition, games such as Star Wars: The Old Republic, Star Trek Online, Dungeons & Dragons, and Lord of the Rings Online all launching as subscription games, but having to rapidly transition to a freemium model of some kind despite enormous initial expectations.

Where Did the MMO Fail?

So what has happened? World of Warcraft’s initial success came from not just creating a better MMO than had previously existed but by innovating with guilds and raids, to sustain an extremely loyal engagement over time. This leveraged social bonds as well as regular events and updates—something that wasn’t being done anywhere else at the time. They backed this up with blockbuster updates, building up the anticipation long before they were released. The trouble is even these great techniques can’t sustain games forever. In the end audiences tastes change, as do their lifestyle choices and, despite lots of attempts, none of the more recent released MMOs have captured the same level of audience as World of Warcraft. More than that, the competition for the time and attention of that player also change and the alternatives made it easy for many players to move on to something new. Not always another MMO, sometimes a game as simple as Candy Crush Saga or Clash of Clans can fill the void. These kind of social and mobile games not only satisfy different social playing needs but inevitably make us question the ongoing expenditure of a game subscription.

Social Games Invited Everyone to Play

Games such as Pet Society14 and FarmVille, which launched in 2008 and 2009 respectively, went further than that. They didn’t just target the already converted players, they unlocked a new, more mass market, audience through their integration with Facebook. What I still find remarkable is the way these games delivered the experiences in an ongoing way. They were constantly updated, even if only to make a tiny tweak to gameplay, remove bugs, or add minor content changes. The innovation was not in the gameplay, after all these new gaming players didn’t have the time or inclination to get into complex game mechanics. It was in the way they responded to real player behavior by collecting data and measuring whether each change made improved the game or not. Of course they also brought with them the freemium model. Anyone and everyone could play the game as long as they wanted without paying, but to make progress or to access unique experiences you would want to spend money. Usually to speed up the gameplay.

Now it is Mobile’s Turn

Of course, a number of mobile developers such as King and Supercell have followed suit, bringing the service approach and freemium business model to their mobile and tablet games. With the success of Simpsons Tapped Out and Real Racing 3, even EA’s Nick Earl announced that he was “pivoting sharply toward free-to-play models instead of the pay-once ‘premium’ business model.”15

Building games as a service means almost inevitably we end up adopting the freemium model. But what about the tarnished image of F2P we have talked about? What does it mean to our ability to be creative?

Players are learning about the nastier tricks and techniques used in different games and unless we change our focus from monetization to delivering better service we may just lose them. But on a more positive note the transition to a service mindset means we can launch the �smallest, least risky build of our game (minimum viable product) and get it into the hands of players to test and show us how they like it.

Moving to a service approach changes not only the way you think about the game, but also about how it will be managed and updated. There are technical and cost consequences as well as the need to change to a new business model. We have to have the infrastructure to sustain and support our community over time and the tools to help them communicate with us and each other with all the appropriate moderation that dictates.

Free is Not Cheap

This is costly and resource hungry. It also requires different planning, maintenance, and development skills. Fortunately there are lots of “off-the-shelf” technologies out there that mean it is possible, if you plan it in advance. However, even with the simplest service you have to assume that the need to continually keep your game “alive” with content, events, and functional updates will mean that as a rule of thumb you should plan for at least 80 percent of your total development costs to arise after your initial launch.

But How Does This Lead Us Into Greater Creativity?

Let’s take three cliché looks at how people become video game designers. The first is the “old school” designer who learnt their trade by making games for studios, which in turn supplied their talents to publishers. They worked on games that had fixed released dates, planned months (if not years) ahead because they had to compete for precious space on the shelves of the game shops on the high street of your local town. Next we have the “indie-ism” designer, the multitalented self-contained artist/coder savants who start out having something they want to create and then learnt through their own mistakes. Many of these couldn’t care less about the money or arguably about what their audience wants to play, but they have an attention to detail about the perfection of their game concept that takes them forward. The last type is the “reborn vets,” often a highly experienced coder or artist who has moved away from the big projects, wanting to make the game their former employers were too blind to see, and who admits that they had to learn the hard way in order to fully appreciate the design process and in particular the impact of unintended consequences.

All of these introductions to games design are perfectly valid but the trouble is that they all focus on the game experience rather than the player experience. The move to a service means we have to consider the journey not only of our game character over time, but also the journey of our player.

What Has This Chapter Been About?

This introductory chapter has been about looking at where the games industry has been and the impact that the changing business model has had on that industry over the past few years. I’ve tried to demonstrate how much change there has been and the impact that this has on almost every aspect of design. F2P is often, wrongly, thought of as only something that affects the way we sell our game. What I hope this book will do is allow you to see that it has a much more profound impact than that.

Free2Play is a Symptom, Not the Cause

This is because F2P is a symptom not the underlying cause in my view. The more profound change has been the change from a retail box-product to an online service industry. When we sell a game upfront, all we have to do is to create enough anticipation to encourage the player to get past the purchase point. Is the idea exciting enough? Does it make me anticipate the joy of playing so much that I have no question about the price tag? Is the gameplay good enough to mean that the game reviews support the marketing story? Sure we want to get better reviews. Sure we want players to rate the experience highly. But none of these reflect the longevity of the player’s experience or their lifetime enjoyment. If we are paid upfront we don’t have any incentive to really think deeply about each their evolving engagement with our game.

Game services on the other hand only work if, first, enough players play the game regularly and, second, enough of them are willing to continue to spend some money regularly. Those players still have to anticipate the joy of playing, not just at the start of their experience, but every day. They still have to find and choose our game over almost infinite number of other titles available to them.

Free Requires Different Skills

Going free isn’t enough to attract an audience anymore. Designing games with the freemium model has unique challenges. Not least of this is that because players have spent nothing, they have nothing invested in the game they have just downloaded. If I have paid upfront, I have no choice but to put up with the layers of tutorial, quicktime videos and partner logo images if I want to make the most of the money I have already spent. If I haven’t spent any money I have nothing to lose and I can just switch off if I don’t want to put up with all of that clutter. If we don’t get our freemium players started playing straight away, it’s our fault if they get bored and play another game instead.

The Designer’s Job Just Got Tougher

Your job as a game designer, no matter which type you are, just got tougher and more interesting at the same time. We need to look at design differently and constantly consider new techniques, tools, and data if we are going to rise to this challenge. I believe this will have a Darwinian influence on the industry—we have to make better games or we will replaced by others who do.

This book aims to give you the skills and tools to make better games, not just more profitable ones.

Notes

1 www.apple.com/uk/pr/library/2008/06/09Apple-Introduces-the-New-iPhone-3G.html.

2 www.apple.com/uk/pr/library/2007/01/09Apple-Reinvents-the-Phone-with-iPhone.html.

3 www.apple.com/pr/library/2007/06/11iPhone-to-Support-Third-Party-Web-2-0-Applications.html.

4 http://news.cnet.com/8301-13579_3-57588534-37/apple-now-hosts-900000-apps-in-app-store.

5 Marketing to children has always been problematic and RuneScape denied that it was doing this and had an age requirement of 13. This has now been removed but players under 13 only have access to a limited version of chat (Quick Chat), which restricts players to predefined sentences.

6 The Guinness World Records site records RuneScape as the most popular free MMO with 175,365,991 users in November 2010, www.guinnessworldrecords.com/records-7000/most-popular-free-mmorpg.

7 More details of how the BigPoint DroidX works can be found on GamesBrief, www.gamesbrief.com/2011/11/bigpoint-does-sell-the-tenth-drone-for-1000-eur-but-may-not-have-made-eur-2-million-from-it/.

8 The transition from paid to Freemium was complete by June 2011 according to Flurry, http://blog.flurry.com/bid/65656/Free-to-play-Revenue-Overtakes-Premium-Revenue-in-the-App-Store.

9 This quote comes from me by the way. Check out my slideshare presentation “A Developers’ Guide To Surviving the Zombie Apocalypse” given at a number of locations, but most notably Game Horizon 2012, Casual Connect Hamburg 2012, and GDC Europe 2012.

10 Again me I’m afraid. In my defense there is logic in this and it’s based on the continuous decline in the number of console studios over the past three to four years alongside the increasing costs of development and marketing against the persistent decline in the retail trade. Given these trends, an average of one game per month seemed appropriate at the time.

11 NewZoo’s Global Games Market Report infographics can be found at www.newzoo.com/infographics/global-games-market-report-infographics.

12 This data was presented by Peter Warman of NewZoo at the Casual Connect in Hamburg (February 2012), www.newzoo.com/keynotes/casual-connect-europe-2013-single-screen-metrics-in-a-multi-screen-world.

13 As I am often reminded by UK consultant Gina Jackson, AAA is about marketing budget, not about the quality of the game. However, for the purposes of convenience I am deliberately confusing the two.

14 Pet Society was shut down in June 2013 by EA who had acquired Playfish in 2009 for $400m

15 www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2013-04-02-ea-mobile-boss-freemium-haters-a-vocal-minority.

Exercise 1: Concept Creation

Throughout this book we will have exercises1 aimed at helping designers new to Free2Play design to test out their ideas. This can be for your own use or perhaps you will want to visit our website www.GamesAsAService.net to share your thoughts with other designers who are working through the exercises and compare and rate each other’s concepts.

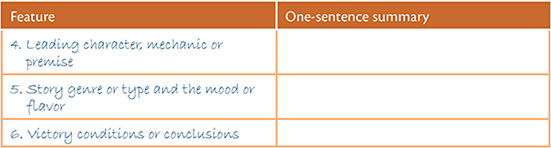

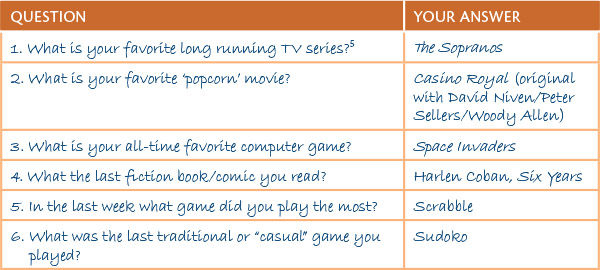

There are lots of game design techniques you can use to create a starting concept. We will explore some of them in this exercise and at the end you should select one idea to use for all of the later chapters of the book. Try answering the following questions as quickly as possible, don’t worry about being accurate, just put in the first concept you think of for each answer, but you can’t duplicate any answer.

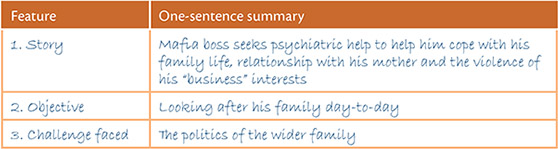

Pick any one of your answers above and describe, in just one sentence, the basic concept of the story; the objective of usually the lead character, but if there isn’t one explain the goal described and finally describe the essential challenge that has to be overcome in the concept, what causes the story arc to be interrupted and difficult.

Now pick a second answer from your selection of 1–6 above and describe in just one sentence, the leading character of that concept or, if there isn’t a character, what the central mechanic or premise is; then describe the genre or type of story and within that answer try to describe the mood or flavor of the concept; finally, describe what the concept presents as victory conditions or, if that’s not obvious, how the concept reaches a conclusion.

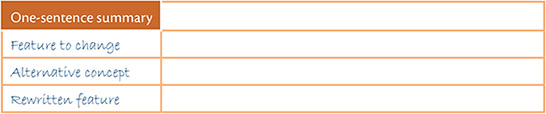

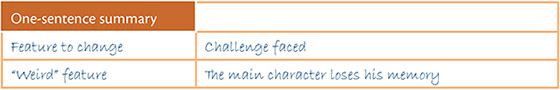

We are going to take these selected concepts and merge them together with the story, objective and challenge of the first concept and the character/premise, challenge and victory conditions of the other. This should form what is essentially a brand new concept, but sometimes we have to throw in something else new, just to be on the safe side to avoid falling into cliché or becoming too derivative. So in order to mix it up a bit, let’s use a six-sided die (yes there is a reason why I wanted six concepts and two sets of three features). First roll to determine which feature of your new game concept you need to revise; where 1 = story and 6 = victory conditions. Then roll again and look at the original six answers you gave, where 1 = TV series and 6 = traditional game.

Rewrite the feature you have randomly selected using the concept answer you have randomly selected as a guide. If the randomly selected concept is the same as you used originally, then leave it unchanged.

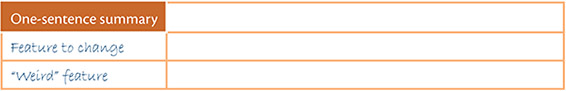

Next we have to throw in something of our own; you could just decide which one to change, but if you need inspiration why not roll that dice again where 1 = story and 6 = victory conditions and add something unique to you. It mustn’t come from the six concepts we described in our answers. It needs to be different, ideally inspired from the other features of our concept; perhaps even something a little weird.4

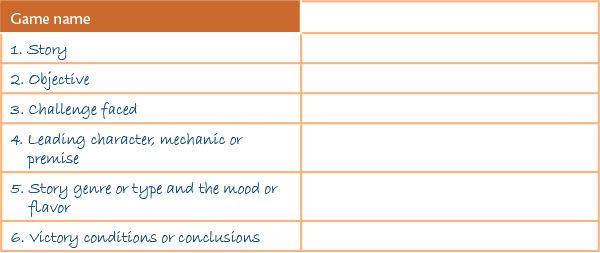

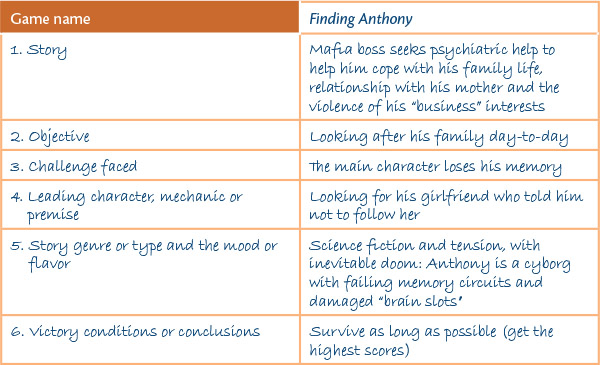

Finally, we need to give this a name. Don’t be limited by the source concepts we used to create our descriptions, instead think about the resulting six features of the new concept and reimagine what this game might be called. We can always come back later if we want to change it. While we are at it, let’s create a final summary putting everything in one place.

That should be enough for us to get started. We aren’t actually looking for an earth-shattering idea right now, just something unique to you we can use to work on through the different exercises in the book. It is not even particularly important whether you think this could be a good game, but you should at least find it an entertaining idea. You can always repeat the process until you are happy to use your idea to practice on as you learn the design strategies for games as a service. Through the later sections of this book we will look at the different elements of the game design from the compulsion loops, game mechanic, context and metagames, allowing you to find ways to realize the best possible gameplay from this idea. If you end up wanting to change the concept; just try working through these steps again and try being playful with each concept you explore.

Feel free to check out www.GamesAsAService.net, where you will be able to upload your results onto a webform that will allow you to create a PDF of the eventual game design and, if you like, share it with others for a comments and comparisons.

Worked Example:

Final summary:

Notes

1 Please note that these exercises and the “worked examples” are intended to help you think like a “games as a service” designer. The results won’t provide a complete or fully fleshed-out game design document. However, it should provide a good start to that process with this specific approach to design. The worked examples are simply intended to provide a comparison with the kind of answers you might want to think about. This is not a real game (deliberately), just a sample concept intended to show that it is possible to come up with non-standard games with this design process. We will post more fully fleshed examples onto the website.

2 By “popcorn” movie, we are looking for the movie you will watch time and again, rather than the movies you rate as being representative of the highest calibre of the artform.

3 The current game need not be a computer game, or even a traditional game. If you played a game of “dare” or even play around with how accurately you park your car, that could still count.

4 Remember Scott Roger’s Triangle of Weirdness, we need some structure around what is new and what is weird, which is why we are picking two familiar concepts and putting them together, then adding one weird/new item to ensure we are introducing originality http://mrbossdesign.blogspot.co.uk/2008/09/triangle-of-weirdness.html.

5 In order to make this example I took the answers to the concept creation questions given to me by my Mum. Hopefully this shows that anyone can do it. I also hope it demonstrates that we can have fun with the process rather always having to try to make best possible creative concept. However, I am surprisingly pleased by the results.