Playing With Others

Some people think of social games as a new phenomenon because of the introduction of Facebook and the way this changed how players shared their experiences. However, over millions of years of evolution, mammals have been playing with others as a way to learn new skills and to test their social position. It’s really only in recent history, with the arrival of the computer game industry, where we started playing alone. Even then, with the arrival of connected computers, Trubshaw and Bartle introduced the first virtual world or Multi User Dungeon (MUD).1 This text-based experience was profoundly different because the world contained real people, people who could type for themselves and communicate (or more likely fight) with you. For those with an imagination and willingness not just to suspend disbelief but to accept the limitations of the technology this was incredible. This also provided an amazing reference point for Bartle to find insight into social playing behaviors as we have talked about in Chapter 2.

From Small Beginnings

Online gaming continued to grow as the quality of connection and games experiences grew. Services such as MPlayer, GameSpy, and British Telecom’s Wireplay used different approaches to provide a central hub for players to help them find and share their online gaming experiences; in particular games such as Quake II or Unreal and, my personal favorite, the groundbreaking Counterstrike.2

However, these services were flawed for many reasons, not least that the technology meant that you had to download a specific client, you couldn’t run them in the browser, and on top of that they usually needed some form of direct integration into the game—something that most developers didn’t have the resources to do.

The other problem is that these games were particularly niche. Only people with the technical savvy (and resources) to link their computers to the emerging internet as well as to troubleshoot these temperamental connections could realistically play.

In 1999, Wireplay had 50,000 monthly active users with more than 1,000 simultaneous peak connections over dial-up (typically 28k or 56k baud) modems. That was one of the largest games services in the EU (probably the largest) at the time, but if you compare that with the 70 million daily active users of Candy Crush Saga it pales into insignificance.

Even with the rise of broadband and connected console games with Xbox Live and PlayStation Network, I would argue that this kind of play remained niche. Of course it grew, but the idea that it might be enjoyed by mass-market players was almost laughable. The growing audience of MMOs was probably as important as the impact of console players in terms of the range of audience. More so if you consider that these games were probably the first to be able to locate significant numbers of female players. People wanted a social context to enjoy games playing together and titles such as EverQuest and World of Warcraft offered that to large communities of both gender.

Footprints in the Sand

However, it took the introduction of social games on Facebook to herald an unprecedented increase in the size of the audience for online and mobile games, bringing for the first time a truly mass-market adoption of casual games. These games picked up on something which in the old days of online gaming we missed: asynchronous play. This was the idea that I don’t have to be online at exactly the same time as you in order to enjoy the experience. I could leave “footprints in the sand” for my friends to discover and these would allow them to feel like they had shared in my experience and enjoyment.

Yes we know that more recently, the social games pioneers such as Zynga, Digital Chocolate, and Playfish have stumbled, but rather than signaling the end of the line for social games, I believe this is just a stumbling start. We have seen a “gold-rush” of developers discovering social values and using data-driven techniques but it has broken the trust of players and left them wondering where the fun went. Something that I hope this book will help you, as a designer, address.

The trouble is that getting under the skin of social play requires that we turn upside-down our expectations of what we currently call social games. Instead of looking at games as single player or multiplayer, we should look at how people behave socially in games and look for patterns of engagement that build trust and confidence. Understanding the role of social elements in games ultimately comes down to understanding people and relationships, not in trying to build on the technical implementations used in games such as FarmVille, World of Warcraft or Call of Duty.

Understanding the Facebook Poke

When considering social play, it’s hard to break things down into simple processes. However, Facebook has a core element that, although it has fallen out of favor, does allow us to get to the heart of what happens emotionally when we use the internet for communication.

The Facebook “poke” is a little more hidden than it once was, but it remains a very simple way to connect to your friends. Poking someone is a transfer of information; it says: “Hey, I thought about you today.” It doesn’t require reciprocation; it’s not demanding. You can choose to respond, inviting further interactions, or you can hide the notification. Facebook even has a simple and effective anti-spamming mechanism included in that you can’t resend a poke until the other party responds. If I poke you and you don’t poke me back, that’s that. This kind of message doesn’t need words, it communicates simply through the action of its use. Receiving this message gains our attention and compels us to find out more if we want to—but the only pressure to respond is internal to ourselves.

For me the most profound realization was in the meaning a poke conveys to its recipients and that this intrinsic “message” is entirely subjective to your relationship with its sender. Think about the different meanings associated when you poke your lover if you are in a new relationship. What about if you have a wife/husband/partner? This message might be flirtatious or even a deep token of love. That message might be completely different if this was to my child or perhaps a close friend. If it’s someone I’ve only recently met, this might have an entirely different context still. A poke can convey other information, for example if we have an arrangement to meet at a pub that day, it can act as a reminder to leave on time; or perhaps if they owe me money, a reminder to pay.

Of course there is a darker side to this kind of communication. If you receive an unwelcome poke, perhaps from a stalker or bully, that can be deeply disturbing.

The point is the message and the medium are not necessarily connected directly. Playing games allows us to see other players who matter to us, whether or not we actually communicate in person. If I know that you can see the purchases or playing decisions I make then that will directly affect my behavior, making me more or less likely to interact in the game depending on the context.

Interdependence Matters

To understand this effect it’s useful to think about how relationships work and consider how players might look at your game as a medium for communications with their friends and other players. This will allow us to find ways to help build deeper engagement as well as to reinforce the positive values that make it more likely that players will gain the emotional engagement with the game as well as to feel safer about spending money with us.

There is a concept called interdependence theory that is used to help us understand interpersonal relationships and in particular why some relationships are stable and others aren’t. For me it also provides a useful way to consider how the social elements in our game can contribute or detract from the interaction with other players. This theory considers why some people have happy relationship experiences and yet have unstable relationships, while other relationships can be stable despite the unhappiness of their participants. This concept was first introduced way back in 1959 by Harold Kelley and John Thibaut in their book The Social Psychology of Groups.3

Measuring Love and Friendship

Defining your relationship with someone is problematic. However, if we take an objective, utilitarian view, we can theoretically compare the love, friendship and affection gained from a given relationship with the effort we expend to maintain it and from this we know if the relationship is “worthwhile.” Of course that’s not something we can do in practice, partly because we are too close to that relationship, partly because all relationships are in a state of flux (we feel different needs at different times) but mostly because we fail to correctly perceive the true value or effort involved. However, for the purpose of this exercise, let’s assume we can make this calculation and let’s call this the “outcome” of the relationship. Of course that’s not all. We also bring to each relationship a set of “expectations.” This isn’t usually a consistent thing. We don’t expect as much from some friends as from others and in some relationships (with family members in particular) we are often willing to put up with a reduced “outcome.”

I Can’t Get No Satisfaction

According to interdependence theory, “satisfaction” with a relationship comes when the “outcome” exceeds the “expectation.” To complicate matters, we inevitably compare the outcomes we are getting from our relationships to the outcomes that others are getting from theirs, and those comparisons affect our expectations as well. This shouldn’t come as a surprise; we are social animals and, in the end, social position is part of the motivation for play in the first place. Because of this we can easily find that we set our expectations so unrealistically high that it seems almost inevitable that we will be unhappy with what otherwise might be the best possible relationship; only to discover the truth too late.

Playing Together

This way of thinking is very relevant to social games. Our players have a relationship not only with the game but with the other players of that game. Each player will have a set of expectations that will create an outcome for each game session that may have little to do with any success they associate with the essential play of the game. Whether they continue playing is dependant not just on players’ satisfaction with the game itself, but on their social relationships and their expectations of alternative services, which might otherwise satisfy their playing needs.

Is it any wonder that this social games market has proven to be more complicated that just having a game that sends “gifts” to your friends and that encourages you to “sell” the game to your friends in return for a few virtual resources?

Other Sources of Emotion

This kind of analysis is all well and good and gives us a sense of the dynamics of social influence on play. However, it can’t of course help us isolate the specific emotional drivers of the players. This matters for games as it’s a key aspect of what we try to engender in terms of play and how we use mood and pace as discussed in Chapter 3. So as designers we don’t just need to think about how players emotionally respond to the gameplay, we have to consider how the gameplay will affect the social context in which the game is played. There are internal forces built into our game design as well as external forces from the social context. Player satisfaction will also be influenced by practical factors such as the ability for players to use our game to fill unoccupied time, the ability for the game to be interrupted, and how others, especially friends, can participate in our shared experience. At the same time satisfaction may also be influenced by opportunity factors such as what the player should be doing instead. Each of these may positively or negatively affect a player’s commitment to playing our game. If we fail to consider these issues we will fail to reach the potential value that socialization can have for our game.

Don’t Be Complacent

There is of course a darker way to view this interdependence model. Does the player’s experience have to be entirely positive? If the outcome exceeds their expectations (and especially the expectations from other games), then this model tells us that they player will keep on playing. There are some grounds for thinking that this might be the case, if our players are new to gaming and their expectations of other available games are sufficiently low, perhaps they might keep playing our game.

I’m not suggesting that anyone deliberately sets out to make a bad game, but it could be argued that there have been some prominent examples of complacency among the original wave of social games. I suspect that this might be a contributing factor to why some of those high-profile early-mover Facebook games lasted as long as they did; in the absence of better gameplay, their players’ expectation of value wasn’t very high due to their relative inexperience in games. The trouble is, you have to ask yourself why new games didn’t just come along to fill the void of quality or at least depth of experience. It’s not like there weren’t other “better” games—whatever that means—available. However, this market was one where the big publishers and developer were spending lots of money4 to acquire users and often were spending a vast proportion of their earnings to simply retain their position. In that context it’s not surprising that other games had little chance of being found.

What Can We Do About This?

When we think about the forces at play in socialization of games it’s clear that we can’t easily affect the expectations a player has about our games. We can try to create anticipation as well as brand values and that will help, however, players will still have their own thoughts and ideas. There are two factors we can genuinely control when it comes to thinking about our game: how entertaining the game is, and how easy it is for players to share and communicate in the game. The more we reduce the effort required to socialize, the more we have a chance to increase the engagement with our audience.

However, thinking about communication brings us back to the “soul” of games as a service. Player behavior evolves as their engagement builds. This concept directly affects the social needs of players as much as their playing needs and it’s important to consider how the social forces adapt as the player lifecycle moves on.

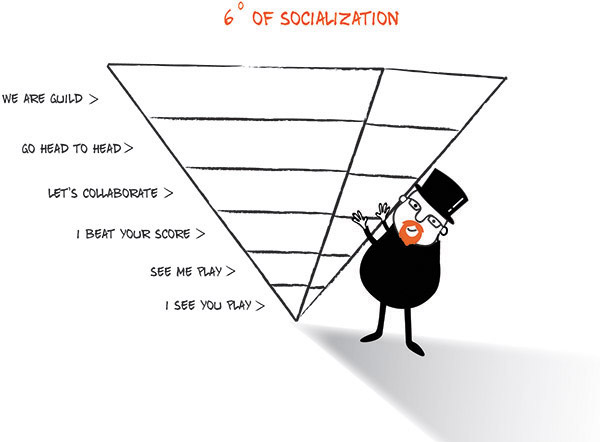

Figure 8.1 Six degrees of socialization.

Six Degrees of Socialization

To help us understand how this works, let’s consider social interaction in different stages, I call them the six degrees of socialization—six core differentiating levels of social interaction that give us a way to examine the engagement needs of players and how we can use this to help sustain and build the audience for our game. More than that, this model helps us think about how to avoid problems that arise when you try to build a critical mass of players by reducing the the social effort expected of your players.

The First Degree—“I See You Play”5

When a player downloads your game for the first time they are in the “learning” stage and generally this is the most vulnerable time from the perspective of sustaining their interest. At this time they have not decided if they are willing to associate themselves with the game and they may have a level of concern about their ability to perform in terms of game skills.

This stage of socialization is passive, almost voyeuristic. First degree players need the reassurance to know that they are not alone and that there are others playing this game. This voyeurism is vital to sustain expectations and to help players overcome the initial disillusionment that comes after the initial download. Other players can provide the vision of the potential of the game and help foreshadow the benefits that the game has to offer in a way that no tutorial or developer-led process can. The point is at this stage that there is no risk to the player. There is only the opportunity to feel welcomed into the community.

The Second Degree—“See Me Play”

Once players become comfortable with their initial experience of the game, and often still within the learning stage, they will become more open to sharing their experience with other players as well as their friends. This requires a little more effort on their part, but provided that the experience is positive for the recipients of these messages (other players, friends, etc.), that’s OK. For example, a simple Facebook post or perhaps a video post of my gameplay (such as Everyplay from Applifier) provides a way for me to share a positive moment from my gameplay, likely an achievement or high score that I’ve achieved. Perhaps even a funny moment that I managed to capture. The payoff comes if others follow me to join the game I am playing and if I get to show off moments of success.

The Third Degree—“I Beat Your Score”

The third degree, appropriately perhaps, is where we start to interrogate our relationship with the game. By this point players have probably crossed over from “learning” to “engaging” and their relationship in the game is now deeper and they are probably playing regularly, perhaps even paying already. At this degree the social elements are more direct where players are deliberately comparing their performance and behavior with their friends. Their relative progress starts to matter. This is not always directly competitive, indeed this is still largely about communicating their experience to each other than directly getting involved in each others’ games. There is almost always a bragging element to this (imagine that) from high scores to leveling up, however this is more about players giving themselves a reason to keep returning, playing and interacting with other players in-game.

The Fourth Degree—“Lets Collaborate”

As our confidence with both the game and the social tools grows we start becoming more open to deeper forms of collaboration and even start to expect a level of reciprocation from other players. In some games this can start quite simply, such as visiting a friend’s farm or playing the same map of an FPS game. There may well be competition between players and indeed the purpose of play may even be to beat others. However, the point of this degree is that we increasingly rely on the involvement of others to get the enjoyment out of the game. Indeed some level of collaboration is often vital in order for each player to progress further in the game. This builds stronger bonds and long-term loyalty for our deeply “engaging” players. Of course there are games out there which jump straight to this form of collaboration in games; think about games such as Battleships or Call of Duty’s online play. These are all about playing together. However, these always do this by creating a barrier to entry for some players. The question to the designer is how great is that cost and are the players who might be put off sufficiently important in terms of cost of acquisition? On the other hand, there are games that have tried to offer single-player versions and have then found that converting player to multiplayer or social versions has been problematic. These problems are usually caused by a lack of focus on communicating the values of transitioning to social play. Building strong fourth degree socialization requires a much greater level of effort than that in previous degrees, and requires that players (and the game developer) spends some time nurturing those relationships. Otherwise these communities can quickly collapse.

The Fifth Degree—“Go Head-to-Head”

After the initial level of collaboration we find that the degree of engagement accelerates further and usually the focus will be more directly competitive. This usually requires a considerably greater level of commitment and indeed to extent training. The offline experience becomes essentially irrelevant and the core enjoyment is found entirely through the interaction with other players. This is largely a phenomenon associated with real-time play, but there are some examples that leverage asynchronous play as well. A critical mass of users is essential to sustain an experience like this and this will inevitably skew your user base toward players already predisposed to the game (and genre). However, building this kind of interaction from the perspective of the metagame or indeed as a superfan game can be quite effective. Clash of Clans is a great example where the superfan nature has brought together collaborate and competitive elements within an asynchronous game.

The Sixth Degree—“We Are Guild”

The final degree takes socialization to its ultimate level where the social experience becomes more important than the specifics of play, indeed where the game becomes merely the chosen method of communication. That’s a great thing to achieve and something that actually gives the developer a degree of freedom because they can often take that fan base with them into other games.

At this level, players use social tools in the game to manage and schedule their experiences together. They actively plan to participate synchronously, perhaps at regular times of the week, or even daily! The best example of a game that has achieved this status is World of Warcraft, but other examples also exist, notably first-person shooters such as Quake, Counterstrike, even Tribes. For players the real-world connections they make through their clan or guild can be highly rewarding, but the effort needed to sustain them is equally high. It’s probably not a surprise that many a divorce, marriage and affair have happened as a result of people connecting through playing with guilds. Only the most dedicated of player groups will sustain them, but these are the same groups who’ll be your greatest asset, if you let them. Given the right in-game tools, loyal players will provide the social “glue” you need to sustain interest from less committed players.

It’s the Journey, Not the Destination

What I have tried to do through these six degrees is to show that, just like the player lifecycle, social engagement is a journey not a destination. By understanding the concept of interdependence we can try to understand the forces that sustain or break these social groupings. Social forces are, however, different and less controllable than player lifecycle. It’s like trying to build a pyramid out of sand; sometimes the pressure of being at the top of the point causes the grains to fall out of shape. It takes effort to sustain a community. They are the most loyal, but you can’t assume they will be around forever. You need to find ways to not only allow others to take over the positions of your most loyal fans, but to actively reward those who take on those roles.

A Social Pyramid Scheme

One of the lessons of managing online communities is that there is no way we can ever have enough staff to engage with the community as directly as we would like. However, by understanding the six degrees of socialization and providing the right tools we can put the power to recruit, manage and engage with the audience in the hands of our players. This takes a different way of thinking than most social games have taken to date. First we have to remember that guilds and clans tend to be fairly small in terms of their immediate members but they leave a much greater shadow on the community. The people who coordinate the play of their guilds and clans have a particularly vital role and we should find ways in the game to reward them for their effort. The more we value their contribution and find ways to return their investment through gameplay, social prestige and, to be frank, love from the developer team, the greater their commitment will be back to the game.

There is a risk that this kind of thinking could get us in trouble, especially if we look at the way pyramid schemes work. Even organizations such as Amway that use the relationships of their sellers to recruit others to promote their goods have a negative perception. However, we have an audience who love our games and it is only reasonable that we should find ways to reward players who genuinely help us retain or acquire users; provided we don’t resort to cheap, brand damaging tricks.

Notes

1 MUD was the first virtual world, although my first experience of text-based virtual worlds came in 1985 when I first played Shades (a later descendant) on my Apple IIE with a coupler modem. This was the first time I realised the importance of lag; it turns out that it’s difficult to fight in a text based game with a 9600 baud connection. Wireplay still supported MUD2 in 1998 and I had my first contact with Richard Bartle over support calls for that service. I know I’ve already provided this link earlier but this presentation is definitely worth checking out, www.gdcvault.com/play/1013804/MUD-Messrs-Bartle-and-Trubshaw.

2 Counterstrike remains one of my favorite games of all time. Indeed I would claim that Wireplay helped “save” that project. OK, that’s a bit of an exaggeration. We bought the original mod team a set of new computers when they were low on cash and in return the fi fth beta release of Counterstrike was branded “Wireplay.” One of the best decisions I ever made. Sadly, it was only years later that Adrian Manning (one of my former colleagues) owned up that he and two others managed to get their names in the credits. I’ve not forgiven him for not getting my name on that list, despite it being my decision and budget that paid for it. Adrian—consider this my revenge, mate.

3 Interdependence theory is largely about social relationships, rather than the relationship between a player and a game, however, it has great parallels for social games, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interdependence_theory.

4 It’s hard to nail down exactly how much people were spending on user acquisition at the peak of Facebook games but the Fiksu reports suggest that $1.18–1.81 is the typical range for a “loyal user” on mobile, http://www.fiksu.com/resources/fiksu-indexes.

5 This model is an update of the one presented in my article in Casual Connect Magazine. I have adjusted the first degree to reflect players who want to see others who play but are not yet ready to socialise themselves, http://issuu.com/casualconnect/docs/winter2013/3.

Exercise 8: What is Your Star Wars Factor?

This is another exercise where we will continue to explore the themes from Chapter 9. On this occasion we will look at the elusive “Star Wars factor.” This is about how users separate their identity from others using your game as the vehicle. It’s the principle behind why some people will understand what I mean when I say “Han shot first,”1 and why others don’t really understand Star Wars (in my opinion of course). There are special rules and experiences that allow us to include some people while excluding others, especially the more we seek other ways to identify with people than just familial bonds. We naked apes are a funny lot when it comes to socializing.

In this exercise we will explore what elements in your game are designed to create a sense of shared experience and therefore to leverage the retention and monetization benefits as well as, importantly, the viral discovery opportunity that comes from effective meaningful socialization. What social media will you support? Facebook and Twitter are common in the West but what about China, Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, India—all huge games markets. Just as importantly you have to think about why these have meaning, and not only to the player who wants to share but also to their friends, the recipients of those messages. They may not care about your game but the last thing you want to do is put them off because they feel like they are being spammed by their friends, your players. Finally, do we have to build some special experience, perhaps an open application program interface (API) to enable the superfans to make the most of the higher levels of gameplay?

Worked Example:

Note

1 If you don’t know what this means, just type the phrase into Google or ask someone with a copy of the original Star Wars film (Episode IV)—not the special editions … definitely not the special editions.