The Karate Kid

Throughout this book we have talked about design, rhythm of play, socialization, and even agile development in the context of the lifecycle of the player. But none of these chapters have really, except perhaps superficially, addressed the one burning issue of all developers engaging in Free2Play design—how do we make any money?

My objective in the writing structure of this book has been to prepare the groundwork so that in this, the later stages of the book, your game design is already ripe for effective monetization. I’m trying to pull off a Karate Kid moment where Mr. Miyagi2 gets you to clean his car (wax on … wax off), which happened to create a kind of muscle memory that supports good martial arts techniques.

If you have been working through the exercises you should have a game concept in mind for which you will have isolated what elements contain the essential “fun” as well as those elements that create the context, allowing the player to repeat play time and time again. All this has then been applied across the lifecycle of the player and we have used several lenses to review our game from such as the Bond moments or Columbo twists we introduced in Chapter 9, or the ideas of levels of player interaction we introduced in Chapter 8.

Why Should I Buy? (AIDA)

Now we can get down to the meat of making money without fear of compromising the playing experience, but first we need to try to understand what happens when people make a purchase.

The way we buy things has been analyzed in detail for decades and in particular one model remains a core part of sales and marketing theory. AIDA3 (awareness, interest, desire, action) makes us think of the transitional nature of a purchase decision and has been intricately linked with the idea of doing funnel analysis since the 1960s; arguably this is where our use of funnel analysis to help us analyze player behavior from game data came from.

Assuming that we have already considered how to get our game discovered, the important take-away here is that it’s not enough for potential players to be aware of our product, or even interested. We have to create a sense of desire and create a reason for them to act; to get them to take the step to install, play … and then pay.

The AIDA model is important for designer to understand because it provides us with our first understanding of the levers we can use to increase our revenue. We all know that discovery is a problem and that we can only generate money if we first have people finding our game. That leads us to identify strategies that can increase the proportion of target players becoming aware of our game. Taking this as the only criteria would be a mistake of course, because it becomes increasingly expensive and inefficient if we don’t also take into account the audience who are likely to be interested. We can’t take this interest for granted, as we have already said, and we need to stimulate that interest as part of our marketing effort but more than that, if we are to create action we have to provide a sense of urgency. Making any purchase is risky and the dynamic of the uncertainty of the outcome of a purchase against the consequences of not making that purchase contribute to buying anxiety. These are further complicated by the social consequence of such a decision (what will others think?) and other more practical needs we might have at that time.

Games are essentially luxury products, which means we have to go further than just demonstrate that the player needs our product. We have to create the conditions that allow them to give themselves permission to play and purchase. We shouldn’t be afraid to admit our products are valuable to their players. We can confidently offset players’ natural uncertainty by creating an expectation of delight. We can build in social value, even make clear to users what they might be missing out on, and this will help them make that step to invest in our game. However, to do this we have to acknowledge that games have a self-indulgent quality, an impractical but delightful value that is different than for more functional goods. It requires the player to be able to set aside their other needs for a period of time, something some call the “abnegation of responsibility.”

Let Me Off the Rollercoaster

It’s something people do all the time. We know we should do the washing up but we would rather watch our favorite TV program, so we set aside the things we should do in favor of things we want to do; we want someone to let us off the rollercoaster of our mundane lives if only for a minute or so. Doing this and choosing to play a game is easy enough if you are already a committed games player, but for a mass-market audience the option of playing a game used to be considered alien. The Facebook revolution for games was to introduce simple, easy to access games content in a social context, which made it a simple way to communicate with people you care about as well as others who just had a shared interest. Now this revolution has spread across multiple devices and has broken down almost every barrier.

We are All Marketers Now

But there have been consequences and one of them is that as designers we can no longer expect the marketing team to build that excitement. We have to take part of the responsibility and create conditions within the game that help them to engage with our game. We can’t take that step for them. We can remove blocking events, such as poor UI or relying on prior “gamer” knowledge and we can use narrative, art and social context to create anticipation for our game. However, our audience still has to make the decision to play on their own.

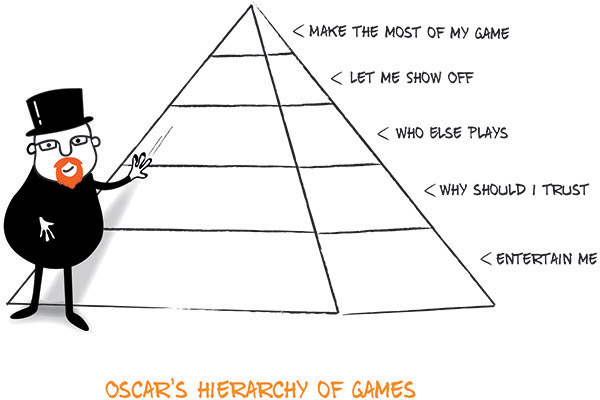

Part of understanding what motivates players is to understand the nature of need states. This way of looking at buyers comes from the model proposed by A.H. Maslow, which suggests different levels of need start that determine the motivation of people. He postulated that until the lower-level needs states were fulfilled, people couldn’t aspire to complete the higher levels. It’s a model that has been debated and questioned endlessly and there is no scientific evidence that the model is valid. And yet it has been one of the single most useful tools I have found in my career. Obviously, games are different from food, water, etc. They are an entertainment product. Therefore, I made a variation on Maslow’s model, arrogantly called “Oscar’s Hierarchy of Games.”

Thinking about this model allows us to make sense of the player lifecycle in a different way. If we don’t entertain our players, there is no game. If we don’t create trust, there is no revenue. If there is no one else playing, why I should continue playing? If I can’t show off, why should I keep buying? Only when all of these levels are satisfied and I still see value in playing and paying, can I really make the most of my game and therefore only then will I spend as much as I want on the game.

Playing is a Delicate Thing

We have to appreciate that the decision to play is a delicate and fragile thing. It requires a level of confidence on the part of the player and willingness to engage. That willingness—like the suspension of disbelief we talked about in Chapter 2—fluctuates differently at different stages of the player lifecycle.

“Discovering” life-stage players will have taken the first step to play your game, but other than time and the bytes of storage needed to install the game they have no investment (or utility) in your game. “Learning” life-stage players are already investing their time and trying to gauge how the game fits into their lifestyle, which makes them particularly vulnerable, but at the same time they are closer to reaching the point where they become, at least in principle, willing to make a first purchase—if they can see that this will make their gameplay even better.

Figure 13.1 Oscar’s Hierarchy of Games.

Buyer Remorse

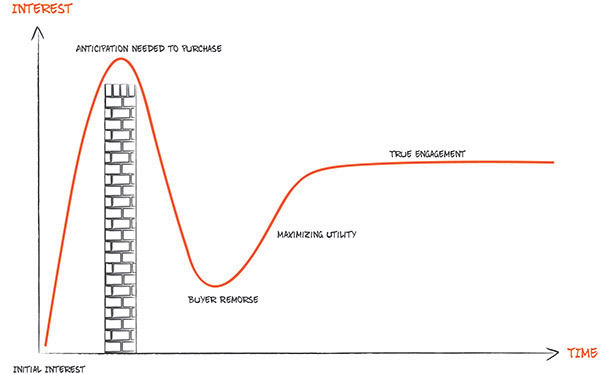

Getting to the first purchase, indeed even getting the player to download at all follows a conversion process. We have to generate enough anticipation of value that exceeds the barriers to install/purchase such as fear of the unknown, cost, fear of looking stupid to others, willingness to invest the effort, etc., of the potential players/payer. Immediately after taking the action to download or buy we find that the player/payer experiences what psychologists would call “post-purchase evaluation” or what I (as a marketer) prefer to call “buyer remorse.”4 This is a sense of regret that comes after making a purchase, especially luxuries, that stems from a number of influences including the guilt of extravagance or suspicion of being overly influenced by the seller. In the case of games, it can be thought of as a form of post-cognitive dissonance brought about by the gap between the anticipation required to buy or download the game in the first place, the reality of their initial experience of play and the awareness of other games they might have selected instead.

Figure 13.2 Buyer Behavior Curve.

The graph above is an adaptation of the Gartner Hype Curve,5 which is normally used to look at the reactions to the adoption of new technology from the initial trigger, through the peak of inflated expectations and into the trough of disillusionment. From my observations, buyer behavior for technology adoption as well as games follows this same path.6

A player’s initial expectations prior to accessing a game, whether purchased or not, have to exceed their expectations of the difficulties and opportunity costs associated with that action or users won’t download or purchase. Players have imperfect knowledge about your game and the value of your game to them, and they will automatically fill in those gaps with something idealistic and personal that you can’t possibly supply. This remorse can be a temporary state as long as we continue to deliver value as a service and as long as they believe they can gain value or utility. The greater the gap between their expectations of the game and the reality of the experience, the more likely they will just churn.

Setting and Beating Expectations

If we want players to survive this buyer remorse, we need to get them through this stage quickly. We should do our best to set their expectations as accurately as possible before they make their decision and, where possible, deliver more than we promised. Think back to Chapter 5 where we talked about six seconds to get them playing. This was specifically to help us deal with manage the initial “remorse” following the download of the game. This chapter also talked about giving players a sense of achievement within one minute. This stage is about taking the player further into the game, to provide deeper engagement, and to encourage them to see the value in the game, reinforcing their confidence. Similar principles apply with purchasing. We need to deliver on the value we are promising again and again, if we want to encourage repeat purchases, and we want to find ways to remind them why that decision to buy was worthwhile. If our users feel we used underhanded techniques to “sell” them goods they didn’t want, they will resent us and churn anyway, probably complaining to most of their friends about our game along the way.

Showing Friends What You Have Bought

Having social elements in games can really help create a positive atmosphere around the purchase of goods. Players tend to feel more willing to try making a purchase in the first place when they see others doing so, but they will also have the opportunity for positive feedback in their choices to buy. This creates a significant reduction in the risk that buyer remorse will damage your player’s commitment to your game. However, we should consider the principles outlined in Chapter 8 in order to get the best effect from such social elements.

Building Utility

If you look again at the Buyer Behavior Curve you will see that after “buyer remorse” comes maximizing “utility.” This is an economics term to describe the invested value of an asset. For the purposes of this book it isn’t about money, time invested, or even entertainment, it’s more about the remaining value a player attributes to the asset. Maximizing utility is about players wanting to get the most of playing the games they have already invested in.

The motivation to continue and work back up this curve is driven by the player’s need to maximize whatever utility remains in the game and the ability of the game to provide ongoing expectations of future value.

Buyer Remorse Business Models

It is usually easier for a premium game to sustain the interest of the player after the initial purchase because the level of investment is tangible. A premium game has to be pretty terrible if I’m going to quit before I’ve given it a good try.

Freemium games can’t assume that there is any utility to exploit and therefore have to put much more emphasis on the ongoing experience of the player. We need to try to build utility through positive experiences before the player feels they have to start spending money. For example, we should try to expose the player to some of our paid-for virtual goods through the free play of the game. Imagine we offered limited access to consumable goods or new aspects of gameplay that would otherwise be exclusive to paying players as a reward for successful play, either directly or through some kind of in-game currency. Players would see these as benefits, valued by the effort required to obtain them. This way we not only align their expectations with the reality (thus minimizing the buyer remorse), but we can use this to create that sense of anticipation encouraging them to make a real money purchase and, importantly, feel good about the value they receive. This approach is about communication the value of our virtual goods, not exploitation.

Tease or Try?

I would also say that this model helps explain one of the conundrums about the limited success of trials and level-based sales. For decades we have seen games offering a “lite” or demo version, perhaps as a cover disk on a magazine. The trouble is that as easily as they increase value, the demo can just as easily diminish the potential sales. The reason is that although a demo will communicate things about our game, they also tend to satisfy our curiosity about that game. It allows us to play for real without having to part with our hard earned cash, dropping us straight into buyer remorse based on the gap between our expectations and the reality, even if the cost/effort to access this was relatively small. Our imperfect knowledge of the game is now cleared away and there is little opportunity to build excitement. If the demo doesn’t lead the player up and out of this trough to re-engage with us then the likelihood is that the player will churn. However, because demos generally cap the experience in some way, the player is left unable to gauge the potential value of the full game as they never get to experience it. Demos suffer, like freemium games, from the lack of invested utility, but (usually) without ongoing scope to retain and tantalize the user for what’s coming next. Trailers don’t have this effect because they simply contribute to the anticipation of the game, the player never gets actually experience the game.

Level-based games suffer from exactly the same problem and are usually a terrible way to monetize a game. Countless otherwise great games have been broken from a commercial perspective because they ignored the need to tantalize players about what was coming next; the same lessons we learn through Chapter 9 with the Flash Gordon cliffhanger.

Engaging Players

I’m taking a long time to talk about this Buyer Behavior Curve for another reason. It matches directly with the player lifecycle we have been discussing throughout this book. The “discovery” life-stage is all about building up anticipation to get users to the point where they download our game. The “learning” stage is about retaining the delicate, tentative engagement as the player learns about how the game fits into their playing habits and builds their confidence until they are able to reach “true engagement.” If we look at player lifecycles in this way it reminds us of what’s happening for the player at each stage, and asks us to consider every play and purchase as part of their journey as they immerse themselves within our game. That’s what it takes be build lifetime value.

Premium Problems

As we have talked about in Chapter 5, the different business models affect buyer behavior differently. The premium (upfront payment) purchase casts a shadow on the behavior of the user. First the upfront price creates a pay-wall, which adds to the other barriers and blocks the player has to overcome before they access the game. We have to create sufficient anticipation in order to get them to decide to download the game and part with their cash. The effect is that a significant number of people will abort the download as a direct result of the upfront cost. It’s hard to estimate how many people would have downloaded, but looking at the number of downloads in the Paid and Free Chart gives us an idea of the scale. In May 2012 Distimo7 showed that to get in the top 25 Free App Charts in the US store required 38,400 downloads per day, while to get in the top 25 Paid App Charts took only 3,530 downloads per day. Similarly, just for the games category this needed 25,300 downloads for the free chart, but only 2,280 daily downloads for the paid. If we assume this ratio is typical, and that the aggregate quality of the top paid and free games is equivalent, then it’s a reasonable hypothesis that having a pay-wall at all inhibits up to 90 percent of potential downloads daily. That’s an exponential number of potential users we will never play our game. We don’t have the chance to entertain them, to try to convince them to play, to generate revenue from them. Of course there are counterarguments.

Premium Positives

Setting a price above the minimum ($0.99 on mobile) is also a way to communicate positive values about a game and, when combined with a known, trusted brand, you may find that you can get a sizable audience past the pay-wall. A price tells the player something about the product’s quality, at least in the mind of the developer, and increasingly includes a promise that we will limit the financial exposure of the player. For those players understandably concerned about the never-ending costs of “free” games it makes some sense, but it won’t sustain a service model in the long run.

There are games where this is really the only choice as they won’t have been designed to sustain a service approach. I don’t believe that there is any game genre that can’t work as a service, but that doesn’t mean every design will incorporate that thinking. If you design a one-off product, premium may be appropriate but never go with the lowest possible platform price. That way lays financial ruin.

In addition, a premium price ensures that the player has utility invested in the game, which provides them with an internal incentive to play through the game past their buyer remorse. It’s much easier to keep them playing and, ironically, it makes them more willing to spend money with you again.

Paying Every Way

No wonder the idea of a “paymium” game with both upfront price and also in-app revenue models has a lot of appeal for developers. The trouble is that by charging upfront and inside the game we are breaking the promise implicit in the premium price, that this is all the player will be required to spend. There are some great examples like Rodeo’s Warhammer Quest where the quality of the app both satisfies my desire to play and creates anticipation for future levels, but their failure to deliver regular map updates has meant that I have fallen out of that habit of playing that game, leaving my desire to spend unsated8.

From a buyer behavior perspective, paymium is the worst possible of models. It creates both a pay-wall before purchase as well as a sense of distrust among players who feel there is no end to the demands of the game on their wallet. However, commercially, especially if you have a strong gaming brand, it can deliver a reliable upfront as well as ongoing income stream. This in turn can make it easier for the developer to focus on improving the playing experience. My sense is that in the end paymium is a fudge, a way for designers who are too timid to adapt to the freemium model to find a compromise at least in the short term. My suspicion is that this approach can work, but it will damage the potential size of the audience, caps the spend of players, and damages the lifetime value of the players. Of course you can drop the upfront price later, but you will still have lost huge number of potential players and there will only be a few games where this is worth the risk.

Finally Free

This leaves us with the freemium model, games that monetize through some combination of in-game goods and advertising. There is no pay-wall to cross, but of course there remains the opportunity cost presented by the huge range of alternative games available. Getting players to download your game is no trivial matter as we have already discussed. But once we have the download we have to face a real problem. Players still have the equivalent of buyer remorse but have no invested utility in our game to help them get through that and up to the engagement stage. We have discussed in detail strategies to overcome this problem throughout the book, but particularly in Chapter 5 and Chapter 9. These focus on leveraging what we are best at to sustain the audience’s attention, by making a better game. It is my assertion that this process is so necessary for the survival of a freemium game that it will drive game design forward in a Darwinian way; survival of the fittest game design. Freemium designers in the end have to make better games. But if we can do this, and build confidence and trust along the way, it will be easier for some of those players to be open to spending money with us. Not just once, but if those purchases are themselves satisfying, perhaps they will purchase time and time again.

One important difference between premium games and the freemium model is that we are the retailer inside the game, we are not reliant on the app store to do our retailing for us. There is no competition for where we get energy crystals inside our game, only us. Equally, we can’t blame someone else if we have picked the wrong price, wrong bundle, etc., and no one buys our goods.

I Can’t Get No Satisfaction

Assuming we manage to get our players past their initial buyer (or download) remorse and up into the stage where they are truly engaged we will find it increasingly easier to repeat the process, time and again. But, there are limits to this. Regular spenders often will have a personal threshold8 or budget that they are prepared to spend (or at least a price point below which they won’t think about how much they have spent). They may temporarily go past this limit, but each time they do the risk is that the subsequent buyer remorse will cause them to reconsider their engagement with the game at all. Bill shock—in other words the discovery that you have spent considerably more than you expected on a service at the end of the month—is a genuine cause for concern and will not only lose you a customer, but they will also tell their friends.

However, even if we keep our player satisfied, enjoying our game, that is not enough for them to continue spending money.9 There needs to be a motivation and incentive to help them decide to take the action to make the next purchase. We need to consider every stage, every play, every purchase to be a new start on the lifecycle; with discovery, learning, engaging and churning stages for each element. This is tremendously challenging to perfect, but in the end it is a game design exercise as much as it is a marketing one.

Don’t Nag, Give Reasons to Act

We should of course be careful to ensure that our legitimate attempts to maximize revenue don’t become counterproductive. We can’t afford to be seen as nagging and if we are this will detrimentally impact the longevity of our players, causing them to churn.

On the other hand it’s worth considering the impact of a decision by J.C. Penney10 in the US to remove misleading sales, such as 20 percent off for a shirt that had never been sold in that store at a different price. They also removed misleading pricing, such as $4.99, which of course is essentially $5, but feels like it’s closer to $4. This failed spectacularly and they lost customers and lots of money. Was this because treating your user-base as intelligent is a bad thing? No, even though these policies were actually better for the consumer, they didn’t feel better for the consumer. Seeing a cheaper price for the same item is not the same as being told that the price is cheaper, buying a $60 pair of jeans for $20 feels awesome, even when we know we are being kidded. There is no excitement in finding a “bargain” when you are just told the straightforward price. The way the experience feels really matters. For example, when I am presented with a special offer of 25 percent off a new car in CSR Racing, that feels awesome, even if its impact in the gameplay isn’t all that significant.

Spending Your Subway Fare

Of course how a purchase feels changes according to the circumstances and we should consider the different mindset of the player prior to playing a new level as compared to when they are just about to die because they are running out of health. The psychological principles can be explored by looking at the ideas of Hot Cold Empathy11 where we see people’s decision-making process being affected by their emotional state. The more visceral a physical or emotional affect (hunger, desire, fear) the greater effect this has on our short-term decision-making process. Games are masterful at building engaged emotional experiences. Imagine that you were playing Space Invaders in Tokyo in 1978, you fail to beat your high score for the nth time and you are so mad you want to smash the machine in a rage. If instead of going home and trying another day, you are presented with an option to “continue” by putting in another 100 yen coin12 then you will almost certainly do so. When we are hot with emotions like this we feel compelled to rummage through our pockets and spend our subway fare home. This principle means that we are open to manipulation by cynical companies—it’s a disturbing thing to realize. On the other hand, the lack of emotional engagement can also be problematic. Although this means we can make more rational decisions, we are also likely to underestimate the value of opportunities when we approach a subject matter coldly.

A Warning

You might think that me talking about Hot Cold Empathy means I think we should exploit the phenomena; in fact I believe it’s a warning. If players succumb to a decision to buy only because we “trick” them into it while they are in the throes of some visceral emotion, we will exacerbate the buyer remorse they feel later. Any short-term gain will be irrelevant compared to the ongoing revenue formed from a habitual and rewarding engagement with our players. Service-led experiences need to provide a balance between emotional engagement and delight; we have to care about our users making their second, third, fourth, etc., purchase and still loving our game. That isn’t to say we ignore the value of emotions to help trigger a call to action. If we don’t deliver goods at the point where players engage emotionally we not only lose a sale, but we fail to satisfy what they expect from game—I’m just saying we mustn’t do it cynically.

Can I Afford To Lose?

Another emotion-led factor involved with purchase is the idea of loss aversion.13 This is an economics principle that explains that people will feel a much greater impact from the loss of $100 than the impact they feel from a windfall of $100. Similarly we tend to place a higher value on something we don’t own than something of the same financial price that we do. It has a particular effect when there is some element of social competition at play, making this particularly relevant to game design. There are a number of ways we can use this. The first is called the “puppy-dog sale,” where we imagine that we are a pet shop salesman. A family comes in and the child and one parent are interested in having a puppy, but the other parent isn’t fully convinced. So you offer to allow them to take the puppy home, to see how things go for a week; they can always return the animal after that week. Once the dog is settled into the home, it’s going to be pretty hard for the reluctant parent to convince the rest of the family to return the animal after that first week because they will have to take this away from them. I like this analogy as it also allows us to talk about the biggest problem with relying on fear of loss. What if the new puppy is a nightmare? They might bite cables, eat slippers or leave “presents” on the carpet. It doesn’t take much to go wrong to outweigh any level of loss aversion when the buyer remorse is this palpable and the dog may end up back at the shop before the week is up.

Examining loss aversion lead us to consider the idea of what it is we might be losing. If we use the virtual goods in our game to build utility into the player’s gaming experience then we are deepening the engagement over the longer term, rather than diminishing the lifetime value of the player.

If You Can’t Stand the Heat …

Let’s not forget the influence competition has on loss aversion. If others can see and then admire or disapprove of the goods we can buy/don’t have in a game this will multiply the impact of any loss aversion. This means that if what we offer is obviously “cool,” there might be considerable pressure to spend money on that asset. Of course the opposite is also true, once it has gone out of fashion, the fact that we own the item can suddenly become quite negative in terms of popular perception. Different people have different reactions to social pressure. Some lead, some follow, and others carve their own path; what is consistent is that they need to be seen to act in that way. Part of how we define ourselves is in comparison with others, even in games. We should not underestimate the benefits from finding a way to ensure that players can see others purchased goods, partly as discovery and partly in terms of social capital.

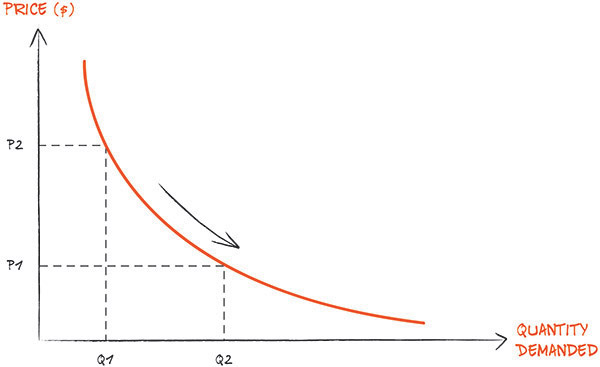

The Price is Right …

There is one core economic principle at the heart of the success of the freemium model and this is the reason why in the end services will continue to be so dominant in for games. Price elasticity of demand is a way to show how demand responds to changes in price, assuming that supply remains constant. There are many factors to take into account, but we typically expect the changes in price to have a relatively constant, say that most games will conform to the classic Exponential Demand Curve, which means that the rate of change in demand itself changes in proportion to the reduction in price. At the highest price, we see the smallest number of purchasers and similarly at the lowest price we see the largest proportion of users taking up the game. In this case each time we reduce the price, the proportion of new players we can acquire will increase by a larger proportion. The biggest difference will be between free and any minimum price. When we are selling goods upfront, our objective is usually to find the optimum price in order to obtain the largest number of users. However, by removing the initial price we move the spending decision into the game, where there are no other competitive suppliers. The same mathematics shows the effect on price of an increase in supply for the same level of demand causes the price to drop in the same way. Given that we already have an almost infinite supply of good games content on the Apple and Android app stores there is no doubt in my mind that this would have naturally driven the price down to free anyway.

Figure 13.3 Exponential Demand Curve.

Affecting Demand

There are factors that affect the nature of these curves, including brand loyalty or marketing hype, which can affect the elasticity, perhaps even making it possible that reduction in price to free might have little benefit to the overall audience. It is also true that moving to free only unlocks access to an audience who will now be available to target with goods from inside the game, it doesn’t necessarily mean that those users will spend. There are some reasons why we might adopt a pricing strategy that doesn’t target the “optimum” balance for price elasticity of demand. We might, usually for competitive reasons, reduce the price to gain market share or increase the price to position our content at a premium. As we have already mentioned there is value for a premium approach where you select a significantly higher price than the “default” in order to communicate the game’s quality and brand. However, unless you have an exceptional brand that has no repeatable value, then you will almost inevitably be better off with a well implemented F2P model.

Freemium, at least according to the consultants,14 is a model that allows players to pay at the level that most suits them. That should mean that we get every possible combination of price and users. The trouble is that’s not quite true. As we have already noted, the second and subsequent purchases are affected by the context of the previous experiences and the changing nature of risk.

Pricing and Risk

Different types of goods have different risk profiles and this affects the how much involvement15 a user will take in their decision-making process. Complex goods tend to require a greater level of investigation, even when the cost isn’t all that significant. A simple consumable good, such as an energy crystal that gives me a temporary boost to performance, is a low risk in the short term. It’s usually cheap, cheerful, and has no long-term complications as it disappears after use. This isn’t a complex decision, but the context of an almost infinite supply of games, players need to be fully immersed16 in your game for this to be a simple decision.

The complexity level increases when we are looking to make our tenth or 100th purchase; longer term questions affect our decision. While consumable items have an immediate value, they don’t (generally) generate any added utility in the game. In fact the paradox is that because they get used and then are gone, in the long term they represent a significant risk to the player. On the other hand, a durable good, for example a well of energy crystals that gives you ten crystals every day (as long as you return) has a sustained benefit in the game, something that I enjoy most only if I come back every day. This type of good generates ongoing value and additional utility for the game. It’s usually at a more significant price than a single crystal and represents a longer-term commitment than perhaps recently converted users might be willing to make, which conversely means it represents a greater short-term risk.

Rent and Buy

The effect of time-based risk and pricing is something that became highly important to the success we had at 3UK with the games service. We initially launched with rental games at 50p for three days. Seemed like a great idea at the time, but with the added complexity of a billing API we found it hard to get enough games ready prior to launch. It was a disaster. We failed to get any significant number of sales and had to react sharply, offering full-price games to buy outright at £5 each. The really interesting part came when we analyzed the results of our sales. We saw that the majority of sales were from “buy” games, but we found that there was a significant anomaly. Games with rent and buy versions sold more than three times the others, and rent reflected only 20 percent of the total revenue.

Part of the reason for this success was that presenting two prices with different levels of value proposition makes it easier for buyers to choose the more expensive option, but it also allowed them to choose the longer term, more stable, more expensive option.

Opening the Gateway

Hopefully with all this you can see the importance of the psychology of buying behavior. In practice we can’t identify the influence of what drives a player to buy, but these key aspects can help inform our thinking and increase the chances that we have to convert more players to payers at the same time as building lifetime value; increasing the perceived utility in the game.

The best examples of how we can apply these techniques come during the transitional moments of the player’s engagement with our game. These are also the points that require the most attention in terms of game and monetization design, particularly the first purchase.

As we have said before, after the initial download we find the important lesson of the learning stages is to help deepen our engagement with our players. We want them to stay with us, to become engaged. We need to ensure that we demonstrate that spending money is going to be worthwhile, even an aspirational goal. But it’s not something we expect from the player. Indeed we understand that doing so when their level of interest in the game is at its lowest point is going to backfire on us. It is later, once we have shown them the value of their investments in terms of time and effort and shown them the value of truly engaging that we can start to consider how we convert them to actually buying something for real money. When we do it needs to be what I call a “gateway good,”17 an in-game item that is designed to be so obviously of value that it shows new players that spending money isn’t a big deal.

It needs to be a simple, obvious benefit for the players and at the same time create a level of delight that will charm the player as a reward for investing in the game. This idea of charming and generous delight is important when designing all of our goods as it’s just as important to build retention after the purchase as it is to gain the money for each individual item. More than that, however, a gateway good needs to be a promise, not only of the value of the item itself, but something that sets the expectations for all future purchases in the game. We will look into this more in Chapter 14.

Setting Price

It will probably be quite clear that nowhere in this chapter do I give any specific advice on setting price. I appreciate that might be frustrating, but it’s deliberate as (of course) I want to limit how quickly this book goes out of date. The other reason is that every game is different. We usually have a minimum price we can sell any items for, based on the platform; for iOS this is $0.99. This is useful for low-pain threshold items, but as we have already stated elsewhere charging higher than the minimum payment allows you to communicate something about the value of the game or in-game virtual good. More interesting is the dynamic of changing price. The price elasticity concept should apply to goods inside your game as much as it does to whether players buy upfront or not. However, there is no competition for virtual good suppliers for your game, and the decision to purchase is specific to their playing experience. As a result, although there will always be an associated opportunity cost for other purchases, it seems that in-game goods are essentially inelastic.18 This means that reducing the price won’t dramatically affect an increase in sales; that’s not a license to charge a ridiculous amount for those items of course. The only way you can really know what the right price is for the goods you sell is to test it. Use common sense and competitive comparison to avoid obvious mistakes and always start with slightly higher prices that you can easily reduce later. You will get a lot more negative feedback if you put prices up. Then again even this can be mitigated if you introduce new items as “introductory price” as this warns players upfront that the price might change later and at the same time makes purchasers feel special as they were clearly smart early adopters.

Beware Shadows

Whenever we introduce revenue items into the game we have to remember the shadow they place on the experience and in particular how they impact the flow from the game. Interruptions for advertising interstitials can be as damaging to the overall experience as a poorly designed payment process.

Making the decision to make the first payment is a huge psychological barrier for anyone; regardless of the price. If there is anything that gets in the way of them fulfilling that process they will blame you and your game—even if it’s an unrelated, unavoidable problem. Make sure you test this process repeatedly, even after launch as you will have to rely on third-party services at some point in the flow. One of the reasons Apple’s AppStore has been so successful is that the vast majority of its users have already entered their credit card details into the service. That means those users don’t have to do anything new to pay for their items in your game. They will have already experienced the familiar flow and will feel it is safe to do that. However, this isn’t always the case with other platforms like Android and especially when you are using other third-party payment systems like Boku or WorldPay. Using external systems is a very good idea, but your responsibility as a developer is to make sure that the set-up process to spend money with you is done as simply and easily as possible. Trust is the most valuable currency; without it no one will spend real money.

Making Your Mind Up

The more I research the psychological triggers to making a purchase the more it seems to come back to the question of trust. There is a natural aversion to being “sold to” and yet we find ourselves buying goods all the time and sharing our best purchases with our friends. There is a “hunter-gatherer” aspect to the act of shopping, which itself is a source of gratification.

The question of how we support players through the inevitable buyer remorse that comes from the act of downloading or buying items in our game is I believe key to success, but more simply it defines the difference between a product and a service. Do our players “buy” our experience or do they “belong” to that experience? How we respond to the question changes the way we create content—hopefully for the better.

There are some basic ethical principles that all business should all adhere to:

- Disclose any risks associated with your product or service.

- Identify the added features that will increase the cost.

- Avoid false or misleading communications.

- Don’t use high-pressure sales tactics.

- Don’t mask selling as another activity (e.g., market research).

There is good evidence19 that shows that being upfront with users about what is free and what costs money can actually build trust and confidence in the game. That kind of clarity means that there are no bad surprises; no shocks to the bank account. Services have to build trust, it’s the most valuable currency.

Freemium games at their best inspire players to become more deeply engaged; at their worst make them feel used and exploited—and inevitably churning.

Notes

1 Using the term “psychology” as a chapter heading calls for a little more due diligence and scientific research than other chapters and my fast and loose “marketing mindset” couldn’t do this justice without some external advice. So I want to thank Berni Good of http://cyberpsychologist.co.uk for her kind feedback and support in this chapter. Of course any mistakes are my own and, to be clear, I’m not a trained psychologist. The other flaw is that I’m mixing psychological principles and economic principles and, to be further clear, I’m not a trained economist. However, the good news is that I am a trained marketer, and we are used to blurring such boundaries.

2 In the classic 1980s film The Karate Kid where Mr. Miyagi was the caretaker at the school who just happened to be an amazing karate instructor. I’m not referring to the more recent update, which is a fine movie but not the one I loved when I was also being taught karate by my own father.

3 The term AIDA is attributed to E. St Elmo Lewis, an American advertising and sales pioneer, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AIDA_(marketing)#Purchase_Funnel.

4 Buyer remorse is also thought to be linked to the “paradox of choice,” a theory by American psychologist Barry Schwartz in which, as the range of choices increases, the level of distress associated with making a decision also increases. More than that, as the range increases, customers start to expect that one choice will be “perfect” with no drawbacks, and this leads to circumstances where it’s almost impossible to be satisfied with any purchase, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buyer’s_remorse.

5 The Gartner Hype Curve is a tool used by technology companies to understand the potential consumer response to new technology triggers from the initial excessive expectations and how they build up based on the limited information available prior to the release of the concept. This is followed by a dramatic negative realization of the realistic limitations of that technology, at least in the initial practical delivery. However, this disappointment can be recovered as the approach becomes normal and gradually we return to a positive acknowledgement of the technology’s contribution.

6 The buyer remorse curve is based on observation of the sale of games content. However, this is an assumption, a hypothesis, yet to be rigorously tested. However, don’t take my word on buyer behaviors. There are some great books on the subject including Michael R. Solomon’s Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, Being, www.amazon.com/Consumer-Behavior-Edition-Michael-Solomon/dp/0132671840.

7 Distimo’s article on the number of downloads to be able to get in the top 25 chart can be found at www.distimo.com/blog/2012_05_quora-answering-series-download-volume-needed-to-hit-top-25-per-category.

8 In October 2013 Rodeo released a new Region and playable characters which I immediately purchased and playing this has delayed proof-reading this book. I’ve not found any academic sources to support this principle, but I have found in several different businesses that players allocate for themselves a “personal threshold” in their spending. This might be a number of games or goods per month or a subconscious budget. This might appear to be suspended when we offer a retail sale offering cut-price deals across the whole platform, but I often find that the player take their spending into account by lowering their purchase behavior in subsequent months. At 3UK in particular, we discovered that classic retail sales were actually counterproductive; players would spending three times their threshold in the month of the sale but those who didn’t churn through “bill-shock” would subsequently reduce their ongoing spend down to a third of normal over the next two months. In the end we would have slightly less revenue. This might be anecdotal, but I believe it’s something that warrants further study.

9 Bong-Won Park and Kun Chang Lee, in an article in Computers in Human Behavior uncovered that game satisfaction with the gameplay was not enough to ensure the gamer has perception of “value” when confronted with the decision to purchase. See “Exploring the Value of Purchasing Online Game Items,” Computers in Human Behavior 27(6): 2178–2185 (2011).

10 J.C. Penney’s change of strategy may not have been a bad idea, but it was at least poorly implemented and the consequences for the business was dramatic. The following article talks outlines the issues and questions the execution problems, www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2013/04/09/j-c-penney-was-ron-johnsons-strategy-wrong. Additionally, there is a great video on Penny Arcade that compares the J.C. Penney situation with the use of in-game loot drops in Firefall, www.penny-arcade.com/patv/episode/the-jc-pennys-effect.

11 American psychologist George Loewenstein looked at how human behavior was affected by intense, visceral emotions, causing us to act against our best interest when agitated and to potentially underestimate effects when we are not, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empathy_gap.

12 In 1978 the classic Space Invaders game was cited as the reason why the Japanese Treasury had to dramatically increase the production of 100 yen coins, used not just for playing games but also widely in order to use the Tokyo subway system, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_Invaders.

13 Interestingly there have been some studies that question whether the idea of loss aversion even exists; however, I believe that it is useful at least as a lens when thinking about virtual goods design, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_aversion.

14 Again I have to admit to doing this myself. It’s a useful shorthand, but the reality as I explain is more complex.

15 It is useful to learn about the buyer decision-making process and the differences between high and low involvement purchases and the following link has a good short summary, www.tutor2u.net/business/marketing/buying_decision_process.asp.

16 Building immersion is one of the key strengths of games, although there is some debate over what exactly immersion is from a psychological perspective. J. Kirakowski and N. Curran did some interesting research looking at RPG games and immersion which provides a useful framework to think about this, see their chapter “Immersion in Computer Games,” in Computational Informatics, Social Factors and New Information Technologies.

17 The “gateway” term comes from theories about drug-taking and hypothesises that the use of less deleterious drugs such as tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis lead to a movement onto stronger substances. There are many criticism of this idea in particular that it commits the logical fallacy of “post hoc ergo propter hoc,” however it does provide a shorthand that makes it easy to explain some of the attributes we want for our first purchase. I should also stress that this isn’t intended to equate virtual goods with selling drugs.

18 On September 5, 2013, at COL 3.0 in Bogata, Colombia, Jamie Gotch of Subatomic Studios talked about how their data confirmed in-game virtual goods were essentially inelastic within their tower defense game Fieldrunners.

19 In press.

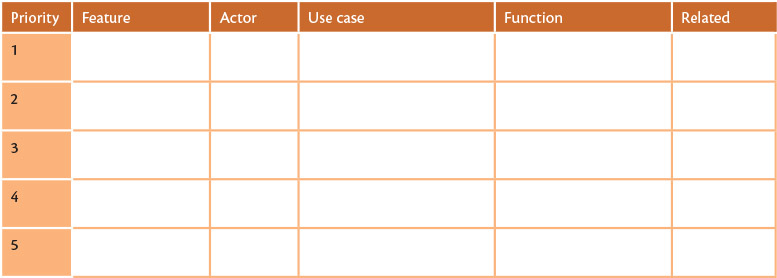

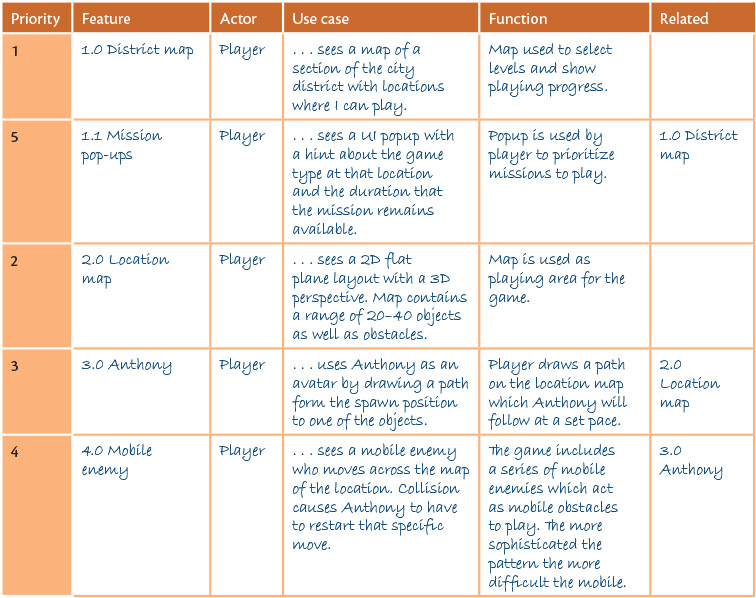

Exercise 13: Writing Use Cases

Now the exercises get a little more serious. So far we have just been exploring our ideas and, hopefully, you have been testing them with paper-�prototypes or perhaps even exploratory coding during voluntary downtime.

Before we start investing real valuable time and coding in earnest we need to make sure we really understand the details of what it is we are going to make. We need to have confidence that we have communicated each element for the development, art and audio teams so that there is no ambiguity over our objectives. We will then ask them to respond to us with their proposed solution to our use cases for us as product owners to sign-off. This way of working vastly reduces the risk of building something different than we intended, although until we go live that is still no guarantee that the result will work as we envisaged.

Start by looking at the core mechanic of your game and break that down into specific separate elements. For each of these elements we will consider who the “actor” is (i.e., the person initiating the use of that element) and the circumstances of that action. You also have to consider what the function is expected to do and the relationship of that use case with other functions. If you are familiar with UML (Unified Modeling Language)1 that can make it easier to communicate in a more formal way; however, it’s not always necessary.

You will want to repeat this process for each of the features of your core game mechanic as well as each feature in the context loop and metagames.

Finally you need to determine the priority of these use cases in absolute order. This means marking the most important feature as number one and then working down from that priority with only one feature occupying each priority number.

N.B. if you want to do this online, the system will allow you to list lots of different use cases and then prioritize them as needed.

Worked Example:

Note

1 Personally I’m not as familiar with UML as I would like to be. It is a useful standard and helps with the communication with developers and data analysts. To find out more about UML check out www.uml.org.