History

1977 was a big year for American nerd culture. One of the biggest events happened in May, when George Lucas’ Star Wars blasted onto the big screen. Star Wars thrilled audiences with unprecedented special effects, unforgettable action sequences, and a fascinating new mythos. Star Wars was much more than just another hit movie, of course. Lucas shrewdly negotiated with the studio for rights to merchandise toys and other products based on the film. After watching the movie for perhaps the hundredth time, kids could go home and set up confrontations between the Empire and the Rebellion with their own action figures and play sets.

Four months after Luke Skywalker destroyed the first Death Star, Atari released the Video Computer System (VCS). If Star Wars redefined the Hollywood blockbuster, the VCS redefined the videogame, firmly moving the industry away from units with built-in games like Pong to a world of interchangeable cartridges and peripherals. As with Pong and the founders’ earlier game, Computer Space, Atari wasn’t the first company to introduce these innovations, but they were the first to successfully diffuse them to the American public. However, the glorious future of the VCS was anything but evident in 1977.

Fathom running on the Stella emulator.

Fathom (1982, Imagic)

While not nearly as successful or prolific as Activision, Imagic made its case for best third-party Atari 2600 publisher with games like Fathom. Rob Fulop’s classic is a multiscreen action adventure that alternates play as a dolphin or seagull in your quest to find a starfish that will give you a piece of Neptune’s trident. Once the trident is assembled, you can then free Neptune’s mermaid daughter from her sea prison. In true competitive fashion, be sure to check out Activision’s similarly water-themed Dolphin (1983), where you play the titular mammal in a race from a pursuing squid, using audio cues to avoid obstacles.

Like its rival systems at the time, the Fairchild Video Entertainment System (VES), which was released in August 1976, and the obsolete-at-launch RCA Studio II, which was released in January 1977, the VCS sold only a few hundred thousand units in its early months. All three systems suffered from competition from bargain bins full of Pong-clones, which had oversaturated the market after the introduction of General Instruments’ AY-3-8500 “Pong-on-a-chip.” These systems often advertised four to six games that were usually just subtle variations of the same basic tennis game—all for $100 or less. The VCS’s initial price of $199 (over $700 in today’s money) was a substantial investment, and the modest library of game cartridges certainly didn’t help the launch. However, an influx of funds from parent company Warner Communications supported Atari during these years and a growing supply of quality game cartridges, advertisements, and positive press helped Atari sell millions of VCS consoles by 1980.

The first VCS units shipped with two joysticks,1 a single pair of paddles, and the two-player Combat cartridge, which contained several tank and plane action games inspired by Atari arcade games. The eight other game titles, several of which were also loose interpretations of Atari’s popular arcade games, were Air-Sea Battle, Basic Math, Blackjack, Indy 500, Star Ship, Street Racer, Surround, and Video Olympics. Although these games were relatively simplistic and not much better than games for rival systems, their variety hinted at what was to come. As an increasing number of rival manufacturers would come to tout their systems’ technological superiority, Atari could boast of a substantially larger variety of games and ways to play them. Ed Riddle’s Indy 500, for instance, came packaged with two steering (driving) controllers, an early addition to the soon-to-be massive array of VCS controller types. Unlike the paddle controllers they resemble, these “driving” controllers did not have stops and could rotate continuously.

HERO running on the Stella interface.

HERO (1984, Activision)

John Van Ryzin’s HERO (Helicopter Emergency Rescue Operation) is an imaginative game in which the protagonist, Roderick Hero, must descend into a mineshaft using his convenient (if physically impossible) prop pack—think Inspector Gadget. Roderick must avoid or blast a variety of dangerous creatures such as bats and spiders, blow up walls with his sticks of dynamite, and eventually rescue a trapped miner before the time limit expires. All in all, it’s a very challenging, fun game with audiovisuals that wouldn’t look out of place on an Atari 5200 or ColecoVision cartridge. Did we forget to mention the rising lava? Dedicated players who sent a photo of their screen with 75,000 points on the score could receive an official “Order of the HERO” badge from Activision.

As celebrated Atari designer Howard Scott Warshaw and others have pointed out, despite the massive research and development budget in comparison to its peers, the VCS was primarily built to play two games: Pong and Tank (a popular arcade game that was incorporated into Combat): “That was it. You had two players, two missiles, one ball, and a playfield.” It definitely didn’t seem like a huge leap from the aforementioned Pong consoles. For many gamers, the Atari VCS just didn’t seem like a good way to spend two hundred bucks.

All this changed in 1980, but it wasn’t one of Atari’s own games that made the difference. Instead, it was a licensed conversion of a game that had swept across Japan and was now taking America by storm: Taito’s arcade blockbuster Space Invaders. Designed by Tomohiro Nishikado and adapted for the VCS by ex-Fairchild employee Rick Mauer, Space Invaders was the first non-Atari licensed game—and what a license it was! The game grossed over $100 million and caused a tremendous surge in system sales as well.2 Mauer, however, reportedly received a measly $11,000 in compensation for all his hard work and genius.3

AtariAge forum member, Ken Netzel describes the appeal of the Space Invaders VCS cartridge:

I heard Atari was going to have a Space Invaders cartridge come out. I decided right then that I would HAVE to have an Atari VCS. My wife and I just got married and got our first credit card. And the first charge on the card was the Atari VCS my wife bought me for my birthday that year (1980) and the Space Invaders cartridge. Back in the day, that was a pretty hefty investment, but we took the plunge. I was hooked playing Space Invaders all hours of my free time.

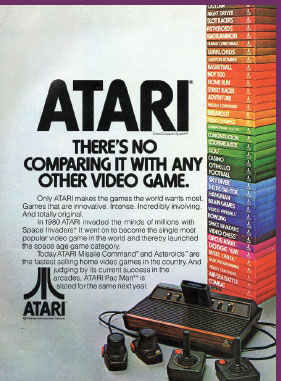

As this ad from the Winter 1981 debut issue of Electronic Games magazine makes clear, Atari was positioned to dominate with its VCS since it was the only system that could boast of so many big name titles.

Mauer wasn’t the only programmer at Atari gifted at adapting high-end arcade games to the limited capabilities of the 2600. Asteroids, ported to the VCS by Brad Stewart, introduced bank-switching, a technique invented by Carl Nielsen that allowed access to cartridge memory beyond the prior 4KB limit. Although the earliest VCS cartridges were generally 2KB–4KB in size, greater memory sizes—including modern homebrews at 32KB and beyond—allowed for increased depth and complexity, contributing to the system’s impressive longevity. Asteroids was another big hit for the VCS.

Space Invaders running on the Stella emulator. Although it didn’t look quite like the arcade game, gamers everywhere were still thrilled by the 112 available play variations, a hallmark of early Atari 2600 titles.

Another notable early title was Warren Robinett’s Adventure (1979), a pioneering graphical action adventure. It was also among the first games with a notable Easter Egg. Gamers who found or knew the secret could find the name of the game’s programmer. Robinett included the Easter Egg to protest Atari’s policy of keeping programmers out of the spotlight and thus immune to better offers from rival companies. The policy might have made sense to Atari’s management at the time, but it ultimately led to an exodus of top star talent and subsequent rise of third-party software houses whose often excellent products would compete directly with Atari’s own lineup.

As this August 4, 1980, news item from InfoWorld shows, the future of third-party software development for consoles was in immediate legal jeopardy.

It all began with the departure of four prolific and talented programmers—David Crane, Larry Kaplan, Alan Miller, and Bob Whitehead. They founded Activision in 1979, one of the earliest and best of the third-party software developers. Activision raised the bar on VCS game quality. Their landmark titles include Pitfall (1982), one of the first running and jumping multiscreen games; Space Shuttle—A Journey into Space (1983), a surprisingly sophisticated flight and mission simulator; and Private Eye (1984), a multiscreen action adventure game. Grossing over $70 million in their first year, the founders of Activision must have felt quite justified in leaving behind their meager salaries at Atari.4

Atari was no stranger to litigation, although courts seldom ruled in its favor. It did score a minor victory in 1972, however, by settling a dispute with Magnavox over arcade Pong by paying a small one-time licensing fee. This arrangement was much more favorable than those Magnavox reached with Atari’s rivals. Magnavox, with the engineering expertise of Ralph Baer, won videogame patent court cases for many years to come. However, when Atari tried to shutdown Activision, their complaint was eventually thrown out. This did lead, however, to a licensing arrangement in which Atari would receive a royalty for each VCS cartridge sold. Other companies took Activision’s lead, leading to the industry-standard licensing model between console maker and software houses still in use today.

Missile Command running on the Stella emulator.

Missile Command (1981, Atari)

Before leaving Atari, Inc., to join Imagic, Rob Fulop programmed this well-wrought conversion of the popular arcade game by Dave Theurer. While the arcade version suggests a nuclear confrontation on Earth, Fulop opted for a sci-fi story between the Zardonians and the Krytolians. He also snuck in an Easter Egg with his initials. Fulop adapted the arcade’s control scheme—which utilized a trackball and three separate fire buttons—for a standard Atari joystick with a single button. Regardless of these and other differences from the arcade version, gamers loved the sound effects and fast-paced action of Fulop’s game. AtariAge forum member “Serious” recalls playing marathon sessions of Missile Command with his father, who would yell, “If it flies, it dies!” when the action got intense.

The success of third-party software companies, especially those composed of their own ex-employees, was bittersweet for the managers at Atari. While companies like Imagic made small fortunes with well-crafted games like the shooters Demon Attack (1982) and Cosmic Ark (1982)—fortunes that formerly would have flowed directly to Atari and Warner—there’s no denying that they also contributed to greater system sales and market penetration, keeping the VCS dominant even in the face of technologically superior competition.

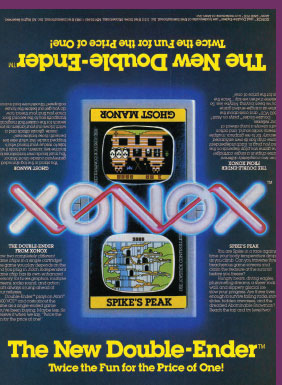

As this Xonox ad for one of their double-sided cartridges demonstrates, third parties would often go to extraordinary lengths to try to distinguish their games from the competition.

Of course, not every third-party game maker was an Activision or Imagic. There were also companies like Ultravision, whose clunky one-on-one fighting game Karate (1983) and copycat shooter Condor Attack (1983) are rightfully forgotten. Incidentally, Condor Attack was a clone of Demon Attack, which itself was inspired by yet another game, Centuri’s 1980 arcade game Phoenix. Atari officially converted that game in 1982 and tried to force Imagic to remove their version from the shelf. Atari lost yet again. Eventually their inability to prevent third-party companies from saturating the market with cheaply made “shovelware” would damage not just Atari’s reputation, but also that of stellar publishers like Activision and Imagic.

Rival system manufacturers, of course, went to great lengths to knock Atari off its throne. Competing systems such as Coleco’s ColecoVision and Mattel’s Intellivision II offered external expansion modules that allowed their system to play VCS cartridges. Naturally, Atari sued, but Coleco countered that they were protected by antitrust laws. Again, Atari settled out of court, settling for a royalty for each adapter unit and clone console sold.

In 1983, Atari launched the “Atarisoft” brand, which published Atari games for rival consoles and home computers. Mostly produced by third parties, these games varied wildly in accuracy and quality, much like Coleco’s and Mattel’s (M Network) similar efforts for the VCS and other competing platforms. The end result of all this sharing and cross-licensing was an unusual type of hardware and software quid pro quo that would be all but unimaginable today—imagine, for instance, if Sony’s PS4 received conversions of Nintendo’s latest Mario and Zelda games instead of just the Wii U.

Montezuma’s Revenge running on the Stella emulator.

Montezuma’s Revenge (1983, Parker Brothers)

The name of this game might conjure up images of tourists racing for the bathroom, but Robert Jaeger’s platform game is anything but crap. The challenging game puts players in the boots of one Panama Joe, an Indiana Jones type out to plunder a deadly Aztec pyramid loaded with traps. Panama Joe must face everything from deadly snakes to creepy “headbones” as he searches for keys, amulets, and, of course, treasure. It’s a stunning achievement for Jaeger, who was only 16 when he created and showed his first prototype of the game to Parker Brothers.

As you can see, Atari’s experiment with the VCS provided many lessons for future console makers such as Nintendo. While they certainly stumbled at times, some of their greatest “mistakes” led to dramatic and far-reaching changes in the industry as a whole. It’s fun to ponder, for instance, what the market would look like today if Atari had simply placated its best programmers, giving them sufficient rewards and recognition to keep them in-house—or succeeded in shuttering their operations through litigation. It might seem a given today, but the current system of publishers and manufacturers we currently enjoy was anything but inevitable.

The first system, known today as the “heavy sixer,” featured dense internal RF shielding (giving it its considerable weight) and six chrome selector switches for power on/off, color/black and white, player A difficulty, player B difficulty, select, and reset. The design featured sharp angles with black plastic and wood-grain styling that gives it a distinctively 1970s aesthetic.

With miniscule system memory of 128 bytes of RAM and Motorola’s 8-bit 6507 microprocessor running just over 1 MHz, the VCS seems at first glance anything but a powerhouse. Sound was limited to two channels, but, if thoughtfully programmed, could support decent sound effects and music. Graphics, while displayed at a fairly low resolution and with limitations on the number of flicker-free objects per line, could draw from an impressive 128-color palette. In fact, the platform’s use of colors and color cycling became the VCS’s signature feature, enabling interesting effects that helped extend the effective life of the console far beyond what could have ever been imagined during its development.

An Atari “light sixer,” which lightened up on the shielding found in the original model. This would be the first of several redesigns.

Later Models

In 1978, Atari released a revised model with lighter RF shielding and a slightly streamlined case. The last VCS revision, released in 1980, moved two of the six switches to the top of the unit. In 1982, Atari released the Atari 5200 SuperSystem. To standardize the product line, the VCS officially became the Atari 2600 Video Computer System, or simply Atari 2600. This design was streamlined like the previous revision, but with an entirely black exterior.

Oddly, when Atari released the 5200, no backward compatibility option was offered, confusing some consumers and hurting system sales. Atari tried making amends with a smaller 5200 system redesign and an awkward add-on module that enabled the backwards-compatibility gamers demanded. Unfortunately, this add-on was incompatible with the earlier, larger 5200 consoles without modification at a service center.

Pitfall II: Lost Caverns running on the Stella emulator.

Pitfall II: Lost Caverns (1984, Activision)

Pitfall Harry, the character in David Crane’s Pitfall series, may not be as famous as Nintendo’s Mario or Sega’s Sonic, but for VCS owners in 1984, he was the man. While the first game, released in 1982, was a smash hit and remains a fan favorite, the sequel is more expansive, allowing Harry to descend deeply into the titular caverns in the Andes. To win, players must help Harry collect his pet mountain lion, Quickclaw, his niece, Rhonda,5 and a diamond ring. The game also features a soundtrack with a four-part harmony, a trick enabled by an innovative custom chip in the cartridge, which would become a common technique on the NES. In short, David Crane really outdid himself with this magnificent achievement. To get your official Activision “Cliff Hangers” badge, all you needed to do was reach 99,000 points and send a photo of the screen.

After the NES revived America’s passion for videogames, Atari reestablished its presence in 1986 with the long-awaited wide releases of a mothballed Atari 2600 redesign, which was unofficially referred to as the Jr., and 7800 ProSystem, which, in addition to playing its own advanced games that could utilize its extra memory, higher resolution, and greater color palette, was almost completely compatible with its older sibling’s games and accessories. The Jr. was Atari’s most significant design departure from the original heavy sixer, featuring a small and thin, black and silver enclosure, which mimicked the styling of the larger 7800. Pushed as a budget-friendly option in comparison with other systems, the 2600 continued to sell fairly well in what had become a very different market.

The impressively small Atari 2600 Jr. shown below the next generation 7800. Both systems could have seen wide release as early as 1984, but corporate and market upheaval meant a critical two-year delay.

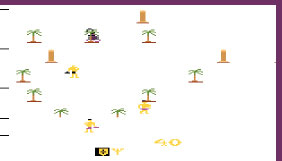

Riddle of the Sphinx running on the Stella emulator.

Riddle of the Sphinx (1982, Activision)

Bob Smith programmed several Atari 2600 games, including Dragonfire (1982, Imagic), Moonsweeper (1983, Imagic), Star Voyager (1982, Imagic), and Star Wars: The Arcade Game (1984, Parker Brothers), but perhaps his most interesting creation was Riddle of the Sphinx. With its well-chosen colors for its in-game objects set against a stark white background, this surprisingly complex adventure game doesn’t look quite like anything else on the platform. You play the son of a pharaoh who must traverse the Egyptian desert in search of treasures that must be offered at various temples in order to appease the ancient gods and lift a curse. In order to check how much time has elapsed, check various player statistics, and perform other key in-game functions, you need to make use of not only the joystick, but also all of the console’s color and difficulty switches. It’s a handful, but the payoff is a rich play experience not often seen on the platform.

The End of the Atari 2600 Line

Atari’s console sales peaked in 1982, after which a glut of poor third-party game titles and bad licensing decisions caused heavy losses throughout the industry. Product dumping, with high volumes of poor-quality games sold at or below cost, caused full-priced, high-quality game sales to suffer. However, two games in particular released that year are always brought up when discussing the fall of the Atari VCS: Pac-Man and ET the Extra-Terrestrial.

In what should have been the deal of the year, if not the decade, Atari got sole rights to Namco’s arcade smash-hit Pac-Man (1980) in 1981. While Atari aggressively promoted and protected their exclusive right to produce Pac-Man and any derivative works, they apparently didn’t bother to actually play their programmer Todd Frye’s rushed conversion. With poor graphics, bad sound, and awkward controls, Pac-Man for the VCS was a travesty of a game and a devastating blow to Atari’s reputation. It seemed to prove that the VCS paled in comparison to the thrills of the arcade. However, it’s not necessarily fair to blame Frye for the disaster. After all, his original design was intended for an 8KB ROM, but he was forced to cram it into a 4KB ROM instead. Atari wrongly guessed that the name alone would generate enough interest to sell the dismal product. Their hubris was so great that they actually manufactured more Pac-Man cartridges than there were VCS systems!

According to AtariAge forum member “Serious,”

Pac-Man was such a terrible game, and such a huge disappointment. I remember feeling like Atari ripped me off (even though my family didn’t buy the game). All of my friends and other families we knew felt the same, and the enthusiasm that everyone seemed to have for Atari games never seemed to be the same after that.

As for ET the Extra-Terrestrial, lead programmer Howard Scott Warshaw seemed like a logical choice for the project. He had impressed Steven Spielberg with his work on the translation of another popular film by the famous director, Raiders of the Lost Ark, which, in 1982, was successfully released as a sophisticated, if obtuse, two-joystick action-adventure. He was also the developer behind Yars’ Revenge, an action game widely considered among the best games on the platform, and was one of Atari’s best sellers.

The story goes that Atari CEO Ray Kassar paid $20 million for the ET license, but the negotiations took so long that in order to make a holiday release, the entire game had to be programmed in six weeks, several months short of a typical development cycle at that time. Warshaw liked both the programming challenge and the money he was able to negotiate for the task, so he began the project in earnest.

Although Spielberg would have been happy with a copycat of Pac-Man, Warshaw insisted on something more original. Miraculously, he managed to meet the deadline, and Atari rushed the cartridge into production with a blitz of advertising. Unfortunately, the end result confused and frustrated many players; guiding the slow ET creature through a seemingly endless series of nearly inescapable pits did not have wide appeal. Although the popularity of the license alone ensured over a million sales of the game, Atari suffered another huge financial loss because of returns and millions more unsold cartridges. Legend has it that Atari ended up burying most of the unsold inventory in a New Mexico landfill.6 All of the millions Atari had spent on licensing and advertising could not compensate for the fact that these were terrible, almost unplayable, games.

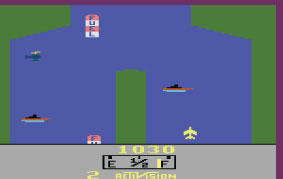

River Raid running on the Stella emulator.

River Raid (1982, Activision)

One of the few Atari VCS games designed by a woman, Carol Shaw’s River Raid is a fast, vertical-scrolling shoot-’em-up with dynamically generated terrain. The game puts players in the cockpit of a fighter plane soaring over the River of No Return, destroying enemy tanks, copters, and jets, all the while avoiding contact with the river’s borders. As if that wasn’t already enough challenge, the plane’s fuel must be regularly replenished by flying over a depot. Players who were able to reach 15,000 points—and snap a photo of their achievement—could receive an official River Raider badge.

By 1984, the Great Videogame Crash had taken a lot of companies out of business, due in no small part to Atari’s own inflexible inventory requirements at retail outlets the year before. These requirements demanded that retail outlets had to stock more product than consumer demand could support. In that same year, Warner Communications sold a large portion of their interests in Atari to ex-Commodore executive and founder, Jack Tramiel, who seemed to have little desire to aggressively pursue the stagnant console market.

While trying to get a grip on the state of the company, Tramiel shelved both the unreleased 2600 redesign and its backward-compatible next-generation successor, the 7800, in favor of new Atari computers (see Chapter 1.4). While a few new 2600 cartridges were made available in 1985 by Activision and other companies, there were no new Atari systems to go with them.

Existing 2600 and 5200 inventory remained in the various sales channels and continued to sell, but almost two years passed before Atari attempted to reclaim their dominance in the home videogame market. By this time, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) had established itself in America, and Atari was left playing catch-up. Ironically, in 1983 Atari had turned down a chance to distribute an early version of the NES. Once established in the United States, Nintendo would prove a deadly adversary, quickly cornering the market with a series of killer games, in combination with price fixing and monopolistic retail policies. As a result, like Sega with the Master System, Atari didn’t stand a chance against the NES, even with a multiconsole strategy.

The Jr., with cosmetic revisions, continued to represent the VCS line until production was stopped completely by the early 1990s. Atari itself ceased to exist as a company in 1996. The name and intellectual assets have been sold and bought countless times since.

Tron: Deadly Discs running on the Stella emulator.

Tron: Deadly Discs (1982, M Network)

While Mattel created several quality officially licensed games based on the cult favorite Disney sci-fi film Tron (1982) for their own Intellivision and Aquarius platforms, it’s arguable that one of the two M Network releases they created for the Atari 2600, Tron: Deadly Discs, was the best of them all. The basic premise is ripped straight from the film: throw your “identity disc” at your enemies before they hit you with their own discs. Once you throw your disc, if it doesn’t hit an enemy, you can either call for its return or wait for it to bounce off a wall and come back. Once the discs start flying, the action heats up fast, making for an incredibly intense experience. For you collectors out there, be sure to also keep an eye out for the special blue Tron-themed joystick Mattel produced for its Atari Tron games. If you like Tron: Deadly Discs, be sure to check out Atari’s stellar conversion of Stern’s arcade classic Berzerk (1982), which features similarly intense gameplay.

The Atari VCS Community Then and Now

The Atari VCS was the first console to enjoy a vibrant, thriving community during its original production run and, as a result, still enjoys a tremendous amount of support today. Countless sites like AtariAge (www.atariage.com) and Atarimania (www.atarimania.com) continue to provide quality information and centralized meeting places for devoted fans and hobbyist programmers alike.

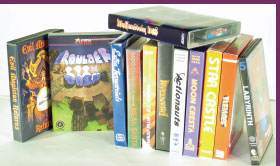

From the mid-1990s through today, homebrew authors emerged to produce a wide range of often high-quality hacks, conversions, and new original games. These include Ed Federmeyer’s groundbreaking SoundX (1995) sound demo program and Tetris clone Edtris 2600 (1995), which got the modern homebrew ball rolling; Ebivision’s platformer Alfred Challenge (1998), which was compatible with multiple worldwide television standards; Xype’s Thrust+ Platinum (2003) by Thomas Jentzsch, which supports a wide range and combination of control options; AtariAge’s Fall Down (2005), which is a competitive twist on the standard platform game by Aaron Curtis that supports Richard Hutchinson’s 2004 AtariVox add-on for in-game speech and high-score saves; SpiceWare’s AtariAge-published Warlords reimagining, Medieval Mayhem (2006); Bob Montgomery’s hectic platformer Elevator’s Amiss (2007), which was coded in the BASIC-like programming language, batari Basic; and the AtariAge-published, officially licensed port of the First Star Software action puzzler classic Boulder Dash (2012).

Both the Atari 2600 and 7800 continue to receive impressive new homebrew releases, consisting of a combination of previously unreleased prototypes, hacks of existing games, and entirely new creations.

Collecting Atari VCS Systems

Because there were over 30 million Atari VCS units sold, working machines are still relatively easy to come by. The four-switch model with the famous wood veneer panels are usually the easiest to find. The Atari 7800 is nearly 100 percent compatible with VCS software and most add-ons, making it a great choice for collectors who want to play both platforms’ games.

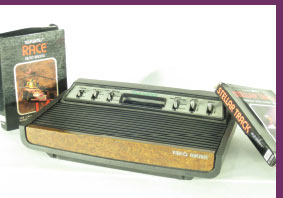

Besides all the variations Atari itself produced, there have been many clones and add-ons for other systems, most commonly from Sears and Coleco. Sears rebranded Atari hardware from the original heavy sixer right through to a sleek custom unit with a unique case, and combination joystick and paddle controllers. The famous retailer sold them under the Video Arcade name, also rebranding games: Indy 500 became Race, for instance. The only cartridges released with the Sears branding that didn’t also have an Atari counterpart were Steeplechase (1980), a paddle controller-based horse racing game, Stellar Track (1980), a strategy game set in space, and Submarine Commander (1982), an undersea target game.

The Sears version of the heavy sixer and a few of the Sears-branded games.

Coleco released both the stand-alone Gemini console, which also featured a single joystick and paddle combination (one above the other) and its popular Expansion Module #1 for the ColecoVision console and Adam computer. Each allowed for high VCS game compatibility, as did the Mattel System Changer for the Intellivision II.

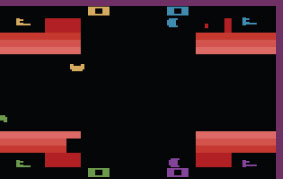

Warlords running on the Stella emulator.

Warlords (1981, Atari)

This conversion of the Atari arcade game by the same name allows up to four players—armed with paddle controllers—to battle for supremacy against other warlords, Breakout style. Occupying each corner of the screen, the warlords are armed only with a shield (rotated by the paddle) to bounce the ball away from their castle walls and into those of an enemy. An engineer named Carla Meninsky did the conversion. A full-on four player competitive game of Warlords is still a great way to liven up a party.

Games range in value depending on whether they are sold as loose cartridges or complete in boxes or sealed, but a decent collection can still be assembled for a reasonable amount. Rarer games can cost into the tens of dollars or even hundreds, with titles such as the first voice-enabled VCS game Quadrun (Atari, 1983), the double-sided cartridge Tomarc the Barbarian/Motocross Racer (Xonox, 1983), and the jumping and matching game Q*Bert’s Qubes (Parker Brothers, 1984), selling for far more than their more plentiful counterparts. Collectors should also consider that many games were released in different styled boxes and cartridges.

Like nearly every system, there are prototype games that were either finished and not released or only partially completed. However, because of the popularity of the system and the timing of the Great Videogame Crash, the 2600 has a particularly large collection of unreleased games, and new prototypes are still being uncovered. Once recovered, the homebrew community often makes these lost titles available for purchase on cartridge or as a download for emulators.

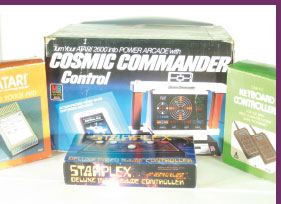

Because the VCS was the first breakout success in home videogames, there was little precedent for developers and publishers to learn from when designing and manufacturing products for it. This led to some pretty novel experimentation, particularly with add-ons, such as the limited release CompuMate from Spectravideo, which consisted of a flat membrane keyboard, additional memory, and the ability to load and save from cassette. In effect, CompuMate turned the VCS into a simple computer system. Some peripherals were tied to their time period, such as GameLine, which featured an oversized cartridge hooked into a phone line that allowed the user to download games for short-term use from a subscription service. Countless others, however, are still quite useful today, such as the Starplex Game-Selex, an external expansion box that allowed instant switchable access to multiple cartridges.

What also helped in this area was that the joystick ports on the VCS were what many other companies such as Commodore and Sega standardized on for their systems. In fact, although it usually wasn’t practical to use single-button joysticks on later systems such as Sega’s Master System or Genesis, multibutton gamepads from those consoles often work just fine when used on the VCS.

Both Atari and third-party manufacturers created a seemingly endless supply of controller types and add-ons.

Besides the standard joysticks, paddles, and other controllers already mentioned, a few others are worth pointing out as well. Obscure releases such as the Foot Craz from Exus, which was a foot mat with five colored buttons that came packaged with Video Jogger (1983) and Video Reflex (1983), contrasted with the more pedestrian options such as the Booster Grip from CBS Electronics, which added extra fire buttons to a standard joystick (a stock ColecoVision controller is also a suitable alternative).

Yars’ Revenge running on the Stella emulator.

Yars’ Revenge (1981, Atari)

Howard Scott Warshaw is often paradoxically called the best and worst game developer on the Atari VCS for his work on both this game and ET, respectively. Whether or not you agree with this claim, there’s no denying that Yars’ Revenge is a remarkable technical achievement and definitely among the best games the platform has to offer. Yars’ Revenge began as an effort to convert the arcade hit Star Castle to the VCS, but Warshaw eventually gave up on that idea.7 However, in the process he’d developed a prototype that was quite fun in its own right. The game offers clever graphic hacks, exotic sound effects, and compelling gameplay, but that’s not all—Warshaw went a step further and helped create a comic book (included in the box), The Qotile Ultimatum!, to explain the backstory.

Atari released wireless controllers that looked similar to their standard joysticks, just with thick antennas and much larger bases. Atari also released different variations on their keypad controllers, which supported overlays and were originally for BASIC Programming (1978) and Codebreaker (1978), but were later restyled and repackaged for use as the Video Touch Pad for Star Raiders (1982), and as the Kid’s Controller for educational games such as Big Bird’s Egg Catch (1983). Suffice it to say, the VCS boasts an amazing range of software and peripherals.

Gamers who choose the emulation route have plenty of great options to choose from. Websites such as Virtual Atari (www.virtualatari.org) offer hundreds of Atari 2600 games playable within a web browser. Software options include Stella, a GPL-licensed product by Bradley W. Mott and Stephen Anthony, z26 by John Saeger, and PC Atari by John Dullea. Almost every modern system also has official compilations of Atari classics available, such as the Atari’s Greatest Hits series for the Nintendo DS, iOS, and Android platforms, among others.

Of course, many gamers will not be satisfied playing these games with their keyboard, touchscreen, or modern gamepad. Gamers longing for a traditional Atari-like joystick experience should check out the Atari Flashback line of TV game consoles. Pre-programmed with many classic Atari games, these units ship with joysticks inspired by the originals, which are also available separately, along with new sets of paddle controllers. Other alternatives include Atari to PC USB adapters, which allow gamers to connect many 2600 controllers to modern computers and other devices for a more authentic experience. Finally, for the ultimate combination of modern day convenience with the simple pleasures of vintage technology, Fred Quimby’s Harmony Cartridge, distributed through AtariAge, allows game ROMs to be placed on an SD card and then played on any Atari 2600-compatible console with a cartridge port.

The Stella emulator running Data Age’s excellent platform game Frankenstein’s Monster (1983).

1 The initial models were the CX-10, which were had slight cosmetic differences and were better constructed than the far more common CX-40 models paired with all later Atari systems.

2 Mark J.P. Wolf, Encyclopedia of Games: The Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming, Greenwood, 2012.

3 Steve Bloom, “30 Secrets of Atari,” www.atarimuseum.com/articles/30secrets.html.

4 Joe Grand and Kevin Mitnick, Hardware Hacking: Have Fun While Voiding Your Warranty, Syngress, 2004.

5 Both Quickclaw and Rhonda were Pitfall Harry’s co-stars on the 1983 cartoon, Pitfall!, which was part of the Saturday Supercade that ran on CBS from 1983 to 1985, and featured a lineup of other popular videogame cartoons, including Frogger, Donkey Kong, and Q*bert.

6 In the 2012 book by Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, Atari Inc.: Business is Fun, this has since been clarified to unsold inventory being sent to a dump in Sunnyvale, California.

7 There have since been two recent homebrew ports of Star Castle, both of which are well worth checking out.