History

The Nintendo Game Boy, which made its North American debut in late July of 1989, was a watershed moment in the history of videogames. It was not, however, the first handheld with interchangeable cartridges. In fact, it was “obsolete” shortly after it was released. Compared to an Atari Lynx or Sega Game Gear, released two and nine months later, respectively, it was a dinosaur: a tyrannosaurus, to be precise.

Despite its cheap, underpowered hardware, the Game Boy did enjoy several key advantages over the Lynx and its predecessors. The first and most obvious was the significant brand recognition Nintendo had achieved in the wake of its Nintendo Entertainment System (see Chapter 2.1). By 1989, there wasn’t a nine-year old in America who hadn’t heard about Mario. Nintendo had also had great success with their Game & Watch handheld systems, which still remain popular among collectors. Perhaps most importantly to parents as well as gamers, however, the Game Boy enjoyed exceptional battery life. Just four AA batteries would last well over ten hours, much longer than the roughly three hours you could expect from the competition—and they required two additional batteries! Later Game Boy systems lasted even longer.

Most decisively, though, the Game Boy series had not one but two killer apps of mobile gaming: Tetris (1989) and Pokémon (1996 in Japan). Eventually, more than 600 games were released for the platform before giving way to the DS series, and today, Nintendo still has the handheld gaming market in its pocket. They owe much of that success to a Russian computer scientist, a Dutch entrepreneur, and an eccentric genius called “Dr. Bug.” But let’s not get ahead of ourselves!

Advance Wars on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

Advance Wars (2001, Intelligent Systems, GBA)

Advance Wars let up to four players battle it out in a turn-based strategy game involving ground, air, and naval forces. Players could connect via a Game Link cable or on a single unit, simply passing it to the next player. It offered 114 pre-made maps, but also a map editor. The game received near-perfect scores from the critics, who praised its “easy to learn, hard to master” gameplay and the sheer joy of the multiplayer mode.

By 1989, handheld gaming had a long history. Most of these earlier units, such as the aforementioned Game & Watch systems or Coleco’s mini tabletop arcade games (see Chapter 1.8), could only play the games built-in to their hardware. The first company to introduce a proper mobile gaming platform was Milton Bradley, who released Jay Smith’s Microvision in 1979. It offered a monochrome 16 × 16 LCD display, and, like the Game Boy, was difficult to see in the absence of bright light because of the lack of backlighting. Motion blur was also a problem, even on the included Block Buster (1979), a clone of the arcade hit Breakout. Cartridges for the system contained more than just games; they had their own microprocessor, screen cover, and control panel. Thus, each game could fully customize the look, feel, and even capability of the unit—certainly a novel feature with exciting potential for game developers. However, much like Smith’s other game system, the Vectrex, creativity and innovation weren’t enough to make the platform a hit. With little external support and only 13 games in its lineup, the Microvision faded from the scene within a few years. Other systems with interchangeable cartridges, such as the Adventure Vision from Entex Industries, failed to make even the impression of the Microvision on the market.1 There just didn’t seem to be much future in the handheld videogaming market beyond what the cheaper, fixed-game units could provide. Once again, entering this market proved that Nintendo was willing to take big risks, convinced it could succeed where others had failed.

The original Nintendo Game Boy and some of its games. Marketing photos tended to show a misleadingly clear image versus the reality of the Game Boy’s low contrast, low resolution screen.

Naturally, the design of the Game Boy fell to Gunpei Yokoi, the janitor-turned game developer introduced in Chapter 2.1. Yokoi was a logical choice for the job, given his reputation for ingenuity and his proven success with the Game & Watch. Unlike many engineers in the gaming industry then or now, Yokoi was interested in what could be done with cheap, readily-available parts rather than cutting-edge components that would only ratchet up costs. He called this philosophy “lateral thinking with withered [sometimes translated as ‘seasoned’] technology.” It was a philosophy that clashed strongly with the dominant ideology of the industry, which still continues to privilege the latest, greatest tech above all else. Yokoi realized, however, that technophiles were only a small fraction of the potential market. Then as now, most people simply don’t care about what’s inside a system, assuming it’s cheap enough to fit within their budgets and “good enough” to let them play their favorite games.

Yokoi was content to design his unit with a 2.5-inch monochrome LCD screen, even though rivals were already promising full-color graphics. Yokoi guessed correctly that a cheaper price, better battery life, and Nintendo’s reputation would more than compensate for whatever geewhiz audiovisuals the competition would offer.

Let’s be clear. Nintendo’s Game Boy was crude, cheap, and obsolete even before it was released. But it had three points in its favor: Tetris, and Tetris. Oh, and Tetris.

Yokoi contented himself with the look and feel of the system, and turned to his partner Satoru Okada to do the internal work. Okada, an electronics engineer by training, had distinguished himself by directing the hit NES games Metroid and Kid Icarus. Okada didn’t quite share Yokoi’s commitment to “weathered” technology. He worried that the design—particularly the “four shades of gray” 160 x 144 pixel display—just wasn’t good enough, and that upgrades were required. He pleaded with Yokoi, who stubbornly held his ground.

Golden Sun: The Lost Age on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

Golden Sun: The Lost Age (2003, Camelot Software Planning, GBA)

This sequel to 2001’s Golden Sun is widely regarded as one of the best role-playing games for the platform. It’s certainly one of the most ambitious, with more than 40 hours of gameplay and brilliant graphics. Although the second game is better than its predecessor, you should probably play them in order to get the most out of the story—and when you’re done, you can transfer your party to this one.

It wasn’t just the monochrome scheme that Okada feared would turn off gamers. At the time, most videogames offered a two-player mode, but how would this work on a handheld? While various wireless technologies had been around for many years, none were as cheap and effective as today’s Bluetooth or Wi-Fi. Yokoi’s rather awkward solution was to connect systems using a wire called the “Link Cable,” which would allow gamers to connect two Game Boys together—assuming they both had copies of the cartridge. It was a kludge, but it would later prove its value to a degree unimagined by its designers.

The Game Boy was an instant hit in Japan, where it landed in shops in late April of 1989. In just two weeks, it had sold 300,000 units—its entire stock.2 Surprisingly, the Japanese launch titles did not include Tetris—for reasons we’ll get into in a moment. Instead, the big game was Super Mario Land, which Yokoi had produced and Okada had directed.

An excerpt of a page from the 2001 premiere issue of Nintendo Power Advance magazine, showing a Game Link Cable scenario between two Game Boy Advances. With the right combination of cables and games, Game Boys from different eras could link together for connected multiplayer gaming.

A well-built platform game featuring the famous Mario characters, Super Mario Land was indeed a great hit, earning stellar reviews and spurring sales of the handheld. Nintendo felt it would be the perfect title to bundle with the unit for its North American debut. The man who changed their minds—and the future of handheld gaming—was a tenacious Dutch entrepreneur named Henk Rogers.

Rogers had moved from the Netherlands to Japan in 1976, starting his own publishing company called Bullet-Proof Software. The company’s claim to fame was The Black Onyx, originally for the NEC PC-8801 computer, but later ported to several other systems, including the Game Boy. Released in 1984, it was one of the first Japanese role-playing games, and sold over 150,000 copies, paving the way for Dragon Quest and other popular Japanese role-playing games.3 This feat is all the more surprising considering that Rogers couldn’t speak or read Japanese!

Four years later, Rogers was at the 1988 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, where he played a fun little computer game called Tetris at the Spectrum Holobyte booth. Rogers had heard about Nintendo’s plans to build a handheld, and he immediately recognized the revolutionary potential that Tetris held for such a system.

Rogers approached Minoru Arakawa, head of Nintendo of America, and convinced him that Tetris would be a much better game for selling Game Boys than Super Mario Land. His argument was simple: Super Mario Land would appeal to young boys; Tetris would appeal to everyone. Arakawa was finally convinced and sent Rogers to secure the licensing rights for the Game Boy.

Mario Tennis on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

Mario Tennis (2001, Camelot Software Planning, GBC)

This GBC title is much more than a simple tennis game. Instead, you get an RPG-style world in which Mario and his friends earn experience points to level up their tennis skills. There are also mini-games and you can use your Link Cable to play against friends. With a Nintendo 64 Transfer Pak, you can connect to the earlier Mario Tennis (2000) on the Nintendo 64 and unlock secrets and “supercharge” your champion. This fun and innovative game earned top scores from nearly every publication that reviewed it.

Like everyone else at the time, however, Rogers had a hard time figuring out just who owned and was legally entitled to license the rights to Tetris.4

Rogers’ first strategy had been to sign deals with Spectrum Holobyte and Tengen, the Atarispinoff, who both claimed they had the rights to sublicense Tetris.5 To cover all his bases, Rogers even secured them from Mirrorsoft, a software publisher in the United Kingdom, yet another company who made a similar claim. Mirrorsoft had bought their license from Robert Stein, president of Andromeda.

Stein, however, had no authority from either Pajitnov or the Soviets—he had lied instead, telling everyone that the game had been created by some Hungarian programmers. The fiasco came to the attention of CBS Evening News, who ended up exposing Stein’s duplicity and revealing Pajitnov as the actual creator. When the Soviet authorities finally got involved, they began by informing everyone that they hadn’t licensed the game to anyone—and all the existing copies of the game were illegal. Stein did eventually sign a deal with them, but not for console or handheld versions. In the meantime, both Spectrum Holobyte and Mirrorsoft had been sublicensing Tetris, further adding to the chaos.6

Rogers decided to fly to Moscow and deal with the authorities in person. Luckily for Rogers, he got there first, and impressed the Russians with his honest assessment of the licensing situation. His only faux pas was showing them a Japanese version of Tetris his company did for the Famicom back in 1988. The Soviets were outraged, but Rogers was able to soothe their anger with a check for $41,000 and a promise of more to come.7 Soon Rogers was signing an exclusive deal for the American handheld version of the game. It took another two months to settle all the legal disputes, but the ink was dry just in time for the Game Boy’s North American release.

It’s hard to exaggerate the significance that Tetris held for the Game Boy and handheld gaming in general. Rogers’ prediction that its appeal would extend far beyond traditional gamers was spot-on. In Augmented Learning, Eric Klopfer writes that he gave a Game Boy with Tetris to his father, who played it regularly despite having no interest in any other videogames. The situation is comparable to games like Farmville, Bejeweled, Angry Birds, and hidden-object games, today. Many “real” gamers and game journalists tend to ignore or disparage these sorts of games, even though they are actively played by vast numbers of people who couldn’t care less about the latest Call of Duty.

Metroid Fusion on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

Metroid Fusion (2002, Nintendo R&D1, GBA)

Metroid Fusion is the sequel to Super Metroid for the Super NES. This time, Samus Aran is infected by the “X” parasite, only to be saved by a vaccine made from a Metroid. The X parasite can mimic whatever abilities are used against it. It’s up to Samus to find and eliminate all traces of the parasite on a research station. If you enjoyed the first two Metroid games, you’ll definitely enjoy this incarnation, which offers much of their style with some welcome enhancements and expansions.

Klopfer adds that the “small screen and flexibility of playing place made it feel less socially isolating and awkward.”8 Even though people could see you playing with your Game Boy, they wouldn’t be able to see how well you were playing—an important consideration for sensitive gamers. We could also add the obvious point that you didn’t need your own television or monitor—there was no need to battle mom or dad for the remote. In short, the Game Boy made gaming a lot more accommodating and convenient for everyone.

While no one knows how many people bought a Game Boy just to play Tetris, it sold 35 million copies and caused at least some to wonder if the game’s hopelessly addictive gameplay is a type of electronic drug—a “pharmatronic,” as Jeffrey Goldsmith of Wired would have it.9 It’s often been called the perfect videogame; the ultimate example of the “easy to learn, hard to master” dynamic. It also relies almost entirely on its gameplay for its appeal; you certainly don’t need advanced graphics or sound to enjoy Tetris. That said, the version that Nintendo whipped up for the Game Boy really did it justice, even featuring catchy music by Hirokazu Tanaka of Metroid fame. It also features an intense two-player competitive mode that connects two Game Boys via the Game Link Cable. Many gamers and critics consider it among the best games ever made, including Steve Wozniak, the celebrated designer of the Apple II discussed earlier in this book. The Game Boy version is his favorite videogame of all time.10

Nintendo’s Game Boy didn’t enjoy a monopoly for long. Just two months later, Atari unleashed the Lynx, which was technologically superior to the Game Boy in almost every conceivable way. Most obvious, of course, was the 3.5-inch color LCD display with a backlit display. Instead of four shades of gray/green, Lynx games could offer 16 on-screen colors from a palette of 4096, the same number of colors the mighty Commodore Amiga could draw from. It also boasted better sound and could be flipped around to accommodate lefties. Instead of just a two-system connection, the Lynx accepted up to an 18-unit network! Unfortunately, the Lynx’s battery life was far less impressive, sucking down six-AA batteries in just a few hours. This fact, coupled with a $179.99 introductory price (the Game Boy was $90 cheaper) limited its appeal.

On the far left is the original Game Boy shown next to an original Atari Lynx (top) and Sega Game Gear (bottom) for scale. To the right of the Atari Lynx is NEC’s TurboExpress and one version of the Watara Supervision, which was a poorly distributed budget competitor to the Game Boy first released in 1992.

The Lynx had originally been developed by the game publisher Epyx, who had called it the Handy. Two members of its design team, R.J. Mical and Dave Needle, had helped develop the Commodore Amiga (see Chapter 2.2). Unfortunately, Epyx was not doing well, and managed to sell the ambitious project to Atari just before filing for bankruptcy. Sadly, much like the Amiga, the Lynx was never able to rise above the competition despite its obvious technological advantages, and sold fewer than 3 million units. Fortunately for fans of this system, it now enjoys a vibrant homebrew community.

Sega’s Game Gear, despite being based on the powerful Master System console technology—and able to use its cartridges with a simple adapter—didn’t fare much better. It boasted a 3.2-inch screen capable of displaying 32 colors at 160 × 144 resolution, and Sega had its popular Sonic the Hedgehog and arcade properties it could leverage. Sega also had a viable response to Tetris in its launch lineup, Columns, which offered similar casual gameplay. Unfortunately, like the Lynx, the Game Gear was a battery hog, and its introductory price of $149.99, while cheaper than the Lynx, was still much more than a Game Boy. Though far more successful, it also failed to pose a serious threat to Nintendo, only selling 11 million units.

A third contender at the time, NEC’s Turbo-Express, was the least successful of all the handhelds of the era, selling only 1.5 million units, despite being arguably the most powerful. A portable version of the TurboGrafx-16 (PC Engine in Japan) and compatible with all of its cartridges, its impressive 400 × 270 resolution couldn’t make up for its high price ($249.99) and lack of big-name games designed for a smaller screen.

Many third-party manufacturers came up with various add-ons to try and make the Game Boy more usable, including an assortment of lights and magnifiers. Some such manufacturers, however, like this advertisement for STD’s Handy Boy demonstrates, clearly didn’t know when to stop.

Pokémon Crystal on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

Pokémon Gold/Silver/Crystal (2000, Game Freak, GBC)

This GBC title is the follow-up to the original Pokémon for the Game Boy. It leaves much of the gameplay intact, but with a new world, creatures, and a greatly improved interface. The game made great use of the new handheld’s color, adding even more personality to the already charming series. The Crystal version, released in 2001, adds the option to play as a male or female, new locations, moves, and much more—it’s probably the one to get, especially if you are new to the series.

The original Game Boy line, through the Game Boy Color, eventually sold over 118.69 million units (with the Game Boy Advance chipping in another 82 million), which is almost double the worldwide sales of the Nintendo Entertainment System. This disparity between Nintendo’s handhelds and consoles has continued to the present day. Consider the data in the table below, in which we’ve juxtaposed the consoles chronologically with the handhelds of their era:

CONSOLES |

HANDHELDS |

Nintendo Entertainment System: 61.91 Super Nintendo Entertainment System: 49.10 Nintendo 64: 32.93 |

Game Boy through Game Boy Color: 118.69

|

GameCube: 21.74 |

Game Boy Advance: 81.51 |

Data from Wikipedia in millions of units sold.

While even today most of the hardcore or “serious” gaming community seems focused on consoles or computers, it’s clear that many other gamers (and many who would probably object to that title) prefer these handheld devices. Gaming had moved from the arcade, to the living room, and now to pretty much anywhere without direct sunlight. In short, the Game Boy was what Clayton Christensen calls a “disruptive” technology:

Disruptive technologies bring to a market a very different value proposition than had been available previously. Generally, disruptive technologies underperform established products in mainstream markets. But they have other features that a few fringe (and generally new) customers value. Products based on disruptive technologies are typically cheaper, simpler, smaller, and, frequently, more convenient to use.11

Christensen also found that it was these disruptive technologies coming from outside that posed the gravest threat to the leading firms he studied. As we’ll see later, it was another disruptive technology—the CD-ROM—that led to Nintendo’s own defeat in the console market by Sony in the 1990s (see Chapters 3.2 and 3.3). It’s curious to think what would have happened had Yokoi not had his way, and the Game Boy ended up being as expensive as the Lynx or the Game Gear—or, more sensationally, if Atari had won the battle over Tetris and offered it as an exclusive game for the Lynx.

The last major event in the original Game Boy’s career occurred in 1996, when Satoshi Tajiri released his first Pokémon game. As a youngster growing up in the Tokyo suburbs, Tajiri loved nothing more than exploring the outdoors in search of insects, a passion that led to his nickname “Dr. Bug.” His father intended for him to become an electrician, but his love of playing and writing about videogames led him to a career as a designer. His debut was Mendel Palace (1989, Hudson Soft), an arcade/puzzle game for the NES. He was also one of the programmers on Shigeru Miyamoto’s The Legend of Zelda.

However, Tajiri’s real breakthrough came in 1990, when he observed children playing a game together on their Game Boys via the Link Cable. He began to conceive a game that would also use this cable, but not just so players could compete head-to-head. Instead, his mind turned back to his childhood love of insects, and he imagined bugs growing in Game Boys and traveling through the cables to visit other Game Boys. When he approached Nintendo with the idea, they swatted him away. Later attempts were also repulsed. Fortunately, at least one person at Nintendo was sympathetic: Miyamoto, Nintendo’s star game designer. Miyamoto adopted his friend’s cause, and this time the company listened.

Miyamoto himself was assigned to help Tajiri develop the idea into the now-familiar game of catching, training, and trading a huge variety of creatures. It took six years, but finally the game was ready. Of course, by this time, the Game Boy was nearing obsolescence, but they were still avidly enjoyed by younger children and anyone who couldn’t afford a newer console. Sales were modest at first, but momentum built steadily as the social networking kicked in over “Mew,” a secret creature. Although the game officially had 150 creatures, this hidden one could only be “caught” by trading with your friends. As unlikely as this ploy might seem, it worked, creating an insatiable buzz for more Pokémon players. The franchise soon expanded into a popular trading card game, manga, anime, toys, and pretty much anything else you can think of.

A scan of the fold-out Pokémon poster from the August 1998 issue of Nintendo Power released in anticipation of the upcoming “Red” and “Blue” games. The “Gotta catch ’em all!” slogan could not only be applied to the in-game activities, but also come to represent all the merchandise that popped up in support of the franchise that fans eagerly snatched up.

It seems laughable today, but when the developers were localizing the game for North America, some thought that gamers here would be turned off by the “cuteness” of the creatures and wanted them redesigned with a more threatening look. Fortunately, the team was able to convince them otherwise.12

Pokémon arrived in America in two versions: Red and Blue. Each version came with different creatures, and, much to the dismay of parents, you needed both to “catch ’em all” and become a “Pokémon master.” The major game publications gave it their highest possible ratings, and sales climbed to 9.85 million, making it both the best-selling role-playing game (although some disagree with the classification), and not just on the Game Boy, but of all time. Everyone agreed that it was one of the best games ever released for the Game Boy, where much like Tetris, the appeal extended far beyond the normal “gamer” stereotype. The franchise has continued to expand into the modern era, but many serious fans still clamor for the original Game Boy versions—especially the “Yellow” version, called Pokémon Special Pikachu Edition, distinguished primarily by a Pikachu who surfs and clearly says “Pika Pika.” This game’s artwork also more closely matches that of the anime, which by the time of its release had become a staple of children’s television programming.

Pokémon Pinball on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

Pokémon Pinball (1999, Jupiter Corp., GBC)

As the title suggests, this game takes the bestselling franchise into a new domain: pinball! It’s also one of the first-ever GBC games to leverage the Rumble Cartridge. While some critics criticized its physics engine, most agree that it was more than just a cash-in on the popularity of the franchise. In any case, if you love pinball and Pokémon, it’s hard to see how you could go wrong with this game.

Like the platform it originated on, Pokémon is clearly a disruptive technology, something that seems cheap, strange, and let’s face it—downright silly—to the established market, but has an overwhelming and transformative appeal for large groups outside of that sector.

Writing for The New York Times, Edward Rothstein tried to explain why the Game Boy was still selling in large numbers as late at 1997. After pointing out the unit’s obsolescence—even when it was released—Rothstein gets at what might very well be the reason for the system’s appeal:

[The] Game Boy is almost bracing. It has so few details that each one becomes essential… In the best games, which range from puzzle games like Tetris, to the newest so-called narrative game, Donkey Kong Land III—leanness provides focus…It begins to seem like an upgrade to solitary pre-tech activities like crossword puzzles.13

While Nintendo’s later handhelds greatly enhanced the audiovisual capability, Rothstein’s analysis is still insightful. After all, plenty of other handhelds were vastly superior technologically speaking, but the charming simplicity of the Game Boy line still managed to draw more sales.

Nintendo finally discontinued the original Game Boy in 2003 after a full 14 years on the market, though the Game Boy Advance was backward compatible and available as late as 2008. Furthermore, many classic Game Boy games can be played on modern Nintendo handhelds via their Virtual Console service on their newest systems. Although the Nintendo DS has the distinction of being the best-selling console of all time, it owes a large part of its success to its humble, “withered” predecessor, the Game Boy.

Nintendo’s cartridge-based handhelds have a long, storied history. Here are a few of the highlights:

• 1995: A commercial failure, The Virtual Boy offered 3D graphics and promised a new era of virtual reality games. Designed to be played on a table, the system required users to peer into an eyepiece, like binoculars. The monochrome graphics were an unsettling red, and some users complained about eye fatigue or headaches. It was rumored that the disappointing sales led to Nintendo’s asking for the resignation of its late designer Gunpei Yokoi, but he claimed otherwise.

The Virtual Boy, shown next to the original Game Boy for scale, was a miserable failure for Nintendo. The company wouldn’t take another stab at a dedicated 3D system until the 3DS.

• 1996: The Game Boy Pocket was sleeker and smaller than the original Game Boy, plus had a better screen with less blur during action sequences. Unfortunately, its serial port was resized, requiring owners to buy special adapters if they wanted to connect their unit to a classic system.

Super Mario Land 2: 6 Golden Coins on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

Super Mario Land 2: 6 Golden Coins (1992, Nintendo R&D1, GB)

This title for the original Game Boy improves upon its predecessor with better graphics, tighter controls, new moves, and a storyline that introduced the world to Wario, a villain who quickly became a favorite with fans of the franchise. The battery pack saves your in-game progress, which is a good thing considering the size of this adventure.

• 1997: The Game Boy Printer was an intriguing add-on that was intended mostly as a way for players to print out their high scores and photos taken with the Game Boy Camera attachment. Unfortunately, it wasn’t a big success, and requires special paper that is hard to find nowadays.

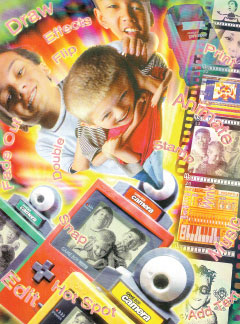

• 1998: The Game Boy Camera was, for a time, recognized as the world’s smallest digital camera. It uses the four “shades of gray” palette of the Game Boy to take pictures at 256 × 224 resolution, which can then be printed out on the Game Boy Printer or shared via a Game Link cable. Perhaps its most famous application was the cover of Neil Young’s Silver & Gold album. At any rate, you’d surely be a hit with the Game Boy Printer and Camera at any Nintendo convention.

A colorful ad for the Game Boy Camera and Printer from the August 1998 issue of Nintendo Power. The camera and its software allowed for a primitive version of the type of interactive virtual reality play experiences common on later consoles, beginning with Sony’s PlayStation 2.

• 1998: Color finally arrived to the platform with the Game Boy Color. Fully backward compatible with the original, this Game Boy could display up to 56 colors from a palette of 32,768. It also offered an infrared port, so Pokémon fans could at last connect to each other without wires or cables. While some games for the Game Boy Color also play fine in the older units, there are also plenty of games exclusive to this system. The memory was increased to 32K, and the processor had a “double mode” that ran at 8.4 MHz, which was used for the GBC-exclusive games.

• 2001: The Game Boy Advance was a significant step forward for the platform, with a new form factor (wide instead of tall) and shoulder buttons. It also upped the resolution to 240 × 160, increased the screen size to 2.9 inches, and added two sound channels. Its CPU runs at 16.8 MHz—twice as fast as the GBC. It’s backward-compatible, but doesn’t have the infrared port—the Game Link Cable had returned. An interesting add-on for the Game Boy Advance was the e-Reader, which had an LED scanner that read e-Reader cards with specially encoded data. Some of the cards included classic NES games to scan in and play, while others unlocked content in games like Animal Crossing (2002) on the Nintendo GameCube (Chapter 3.7) when used with the link cable.

• 2003: The Game Boy Advance SP was another significant revision. Nintendo finally added front lighting, so players could at last play in the dark. It also had a redesigned case that clamped shut like a wallet. These units have rechargeable lithium ion batteries. A later version allows you to adjust the brightness instead of just toggling the light on and off.

Systems shown, left to right: Game Boy, Game Boy Pocket, Game Boy Color, Game Boy Advance, Game Boy Advance SP, Nintendo DS, and Nintendo 3DS.

• 2004: The Nintendo DS is widely regarded as one of the best-ever handhelds. The biggest change was the introduction of a second screen, which accepts touch or stylus input. It has a 256 × 192 resolution, 260,000 on-screen colors, and 16-bit stereo sound. It is oriented horizontally, but can clamp shut like the SP, protecting the screen when not in use. It is backward-compatible with the Game Boy Advance, but not the earlier systems. It, and future versions of the DS, remain Nintendo’s best-selling system of all time.

• 2005: The Game Boy Micro, the last of the original Game Boy series systems, is a much smaller, thinner version of the Game Boy Advance, but isn’t compatible with Game Boy or Game Boy Color games. The company made a big deal out of the interchangeable faceplates, but the tiny system was overshadowed by the popularity of the DS.

• 2006: The DS Lite slimmed down the original DS and improved the display, while retaining backwards compatibility with Game Boy Advance games.

• 2008: The DSi enlarged the screens of the DS and added cameras. It also has rewriteable internal and external storage via SD cards. The only real downside to this model is the lack of a port for Game Boy Advance games. In 2009, Nintendo introduced the XL version, which, as the name suggests, is larger, with screens that have a wider viewing angle.

• 2010: Nintendo’s 3DS introduced stereoscopic 3D—that is, 3D without the need for any special glasses. They also added an accelerometer and a gyroscope, which open up some intriguing options for controlling games. While the unit has fared much better than Nintendo’s earlier attempt at 3D, the Virtual Boy, the 3DS has failed to achieve the same popularity of its predecessor in light of increased competition for eyeballs from smartphones and tablets. An XL version, released in 2012, offers much larger screens, better battery life, and a higher capacity SD card than the original. The 2DS, introduced in late 2013, plays all of the same 3DS games, just in 2D and with a non-folding, slate form factor, making it a budget friendly alternative to the original 3DS and those adverse to the idea of 3D gaming.

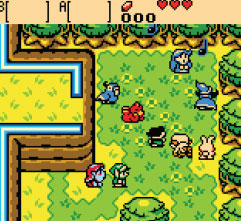

The Legend of Zelda: The Minish Cap on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

The Legend of Zelda: The Minish Cap (2004, Flagship Co., GBA)

Link is second only to Mario in terms of popularity with Nintendo fans, and this game does the venerable franchise justice. The Minish are tiny people, so Link must use the power of the titular hat to shrink himself down small enough to explore their world. This shrinking dynamic is used to great effect in the game’s puzzles. It’s also one of the best-looking games on the platform.

The Nintendo Game Boy Community Then and Now

Nintendo’s Game Boy enjoyed a tremendously broad appeal that extended far beyond the traditional gamer demographics. After all, how else were you going to play Tetris on the go? Although the bulk of Nintendo fans were 8–12-year-old boys, there were quite a few women and girls playing as well. Some of Nintendo’s television commercials showed 30-something-year-old business professionals playing Game Boys as the narrator said, “You don’t stop playing because you get old. But you could get old if you stop playing.” The relatively cheap price of the Game Boy and its long battery life made it ideal for travelers, students, or anyone without easy access to a television.

The Pokémon craze that swept across America in the late 1990s had less appeal for adults. Children were playing so much of the videogame (and the related card game) that some schools banned them. As discussed above, the need to play the game with other people to acquire all the monsters spiked a social gaming movement. It’s hard to exaggerate the impact that the franchise has had on a generation of children, many of whom still play the original game or its many sequels.

One intriguing part of today’s Game Boy culture is in music, where artists use Game Boys to make “chiptunes.” While other systems are also widely used to make chiptunes, the portability and familiarity of the Game Boy make it a fun instrument for performers.

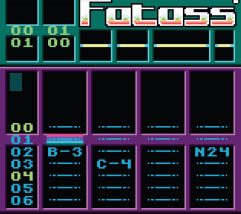

Shown here via the VisualBoyAdvance emulator is Fatass, a music tracker for the Game Boy Color. Many chiptune artists use programs like this to create fantastic, retro-sounding digital tunes.

The Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Ages on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

The Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Seasons/Ages (2001, Flagship Co., GBC)

While both great games in their own right, what makes these games unique is the way they interact with each other—either via passwords or Game Link cable. As the titles imply, one game focuses on weather-based puzzles and abilities, whereas the other is concerned with time travel. Seasons is more action-based, with Ages being more puzzle-oriented. If you complete one, you’re given a password that will create a “linked game” with the other one, changing its story line and ending. Can you say replay value?

Today, there are countless websites that cater to the needs of all types of Game Boy fans, although these skew mostly toward the Game Boy Advance and DS systems. YouTube is full of videos featuring fans playing games, repairing or modifying their systems, or just reminiscing about the good old days. Online forums are plentiful, although few seem to be focused exclusively on the original Game Boy.

There’s also an impressively active homebrew and modding community. The Game Boy Development forums at http://gbdev.gg8.se/forums are a great place to learn about all manner of exciting projects. A recent example is Super Connard, a French cartridge with three different casual mini-games. Most homebrew for the Game Boy line, however, is made for the Game Boy Advance or DS systems. A program called Dragon BASIC, written by Jeff Massung, makes it easy for even novice programmers to create new games for the Game Boy Advance.

Dragon BASIC is an easy-to-use interpreter for programming games on a computer for the Game Boy Advance. Shown on the left is the IDE with the source code for the game on the right. The game was programmed by Jason Bullough and is entitled Chegg.

Collecting Nintendo Game Boy Systems

Acquiring an original Game Boy is neither expensive nor difficult. For units with the inevitable scratched screen, buying and installing a replacement screen can be easily done with an inexpensive kit. It’s also trivial to find and replace the battery cover, which are often missing on systems formerly owned by small children, or very forgetful adults.

However, it probably makes sense for most people to go with one of the later units. The Game Boy Advance SP is a great choice for many people, since it is backward-compatible with the original Game Boy and Game Boy Color, and of course has a nicer form factor and lighting.

Emulating the Nintendo Game Boy

There are many ways to emulate the Game Boy. One of the most popular and versatile is Visual-BoyAdvance. It emulates the classic Game Boy, Game Boy Color, and Game Boy Advance lines, and is available for Windows, Macintosh, and Linux computers. Another option is BGB, which has TCP/IP support for emulating the game link. BGB is also known for its accurate sound emulation, an important factor for chiptune composers. Similar emulators are available for a variety of smartphones and tablets.

Wario Ware Inc.: Mega Microgame$! on the VisualBoyAdvance emulator.

Wario Ware Inc.: Mega Microgame$!

(2003, Nintendo R&D1, GBA

This GBA title features the villainous Wario, who debuted in Super Mario Land 2. Otherwise, the two games couldn’t be more different. This one is a huge assortment of brief mini-games that span the history of Nintendo—there are games based on everything from the old Game & Watch systems to later NES hits like Duck Hunt and Metroid. Several of the mini-games border on the surreal, with one, for instance, having you rapidly clicking the buttons to suck the snot back into a woman’s nose! The casual, “pick up and play” nature of this game hearkens back to the days of Tetris.

If you own a Super NES, a fun option is the Super Game Boy. This special cartridge has a slot for Game Boy cartridges, and some later Game Boy games actually have special enhancements that take advantage of this setup. While this is mostly limited to enhanced audiovisuals, some games, such as Wario Blast, actually let you use the Super NES’s second controller for two-player gameplay. The Game Boy Player is a similar device for the GameCube, but also accepts Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance cartridges. Unfortunately, it doesn’t support the Super Game Boy’s enhancements.

Of course, an obvious problem with PC or console-based emulation is that you lose out on the mobility! Thankfully, it’s also possible to emulate the Game Boy on modern gaming handhelds. The Lameboy emulator offers support for playing older Game Boy games on a DS. There’s also GameYob, which has a number of cool features such as save states and support for a Rumble Pak. It uses the DS’s wireless capability to emulate the game link. Note that both options will require the purchase of a micro SD card and reader, as well as a Flash cartridge.

Of course, you should always check Nintendo’s own Virtual Console store on their latest systems to see if the game is already available as part of that service. Many of the classic Game Boy titles, such as Tetris and Super Mario Land, are sold on the Nintendo eShop for reasonable prices.

1 It should be noted that the Entex Adventure Vision (and the similar Colorvision), which resembled an arcade machine, was intended to be placed and played on a tabletop rather than held in the hands. It was also too fragile and bulky to be carried in your pocket or backpack. In short, it’s not the in the same category as the Microvision or Game Boy.

2 Travis Fahs, “IGN Presents the History of Game Boy,” IGN, July 27, 2009, www.ign.com/articles/2009/07/27/ign-presents-the-history-of-game-boy.

3 Edge Staff, “The Making of Black Oynx,” Edge, January 20, 2013. www.edge-online.com/features/the-making-of-the-black-onyx.

4 See “Tetris (1985): Casual Gaming Falls into Place,” Chapter 20 in Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton, Vintage Games: An Insider Look at the History of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the Most Influential Games of All Time (Focal Press, 2009), for more on the game.

5 See Chapter 2.1 for a discussion of Tengen’s Tetris and the fight over the NES versions of the game.

6 For a detailed account of the Tetris licensing fiasco, see “The Tetris Saga,” Atari HQ, www.atarihq.com/tsr/special/tetrishist.html

7 A great deal of ink has been spilt telling this story. See Harold Goldberg, All Your Base Are Belong to Us: How Fifty Years of Videogames Conquered Pop Culture (Three Rivers Press, 2011) and David Sheff, Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered the World (Vintage Press, 1994). Both give dramatic accounts of the Tetris debacle. Steve Rabin also covers the story in his Introduction to Game Development: Second Edition (Cengage, 2010). Hopefully, there will be a movie soon.

8 See Eric Klopfer, Augmented Learning: Research and Design of Mobile Educational Games, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008, p. 38.

9 Jeffrey Goldsmith, “This is Your Brain on Tetris,” Wired, Issue 2.05, www.wired.com/wired/archive/2.05/tetris_pr.html.

10 Daniel Terdiman, “Woz and I Agree: ‘Tetris’ for the Gameboy is the Best Game Ever,” C|Net, December 11, 2007, http://news.cnet.com/8301–13772_3–9832348–52.html.

11 Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail, Harvard Business Press, 1997, p. xv.

12 Developers Fred Ford and Paul Reiche III designed a computer game in 1985 called Mail Order Monsters, whose gameplay bears a striking resemblance to Pokémon. These two would go on to develop Skylanders: Spyro’s Adventure in 2011, which expanded the concept to include physical toys and a “Portal of Power” interface that transfers data between game or PC systems and the toys.

13 E. Rothstein, (1997, Dec 08). Technology. New York Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/109731363?accountid=14048.