Nintendo Entertainment System (1985)

History

Nearly 30 years after its North American launch in late 1985, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) and its celebrated game franchises continue to thrill millions of gamers all over the world. At a time when many in the industry and the mass media assumed videogame consoles were dead, the NES leapt onto the scene like, well, a certain mustachioed plumber, thoroughly squashing the moribund competition and becoming a new global cultural icon. Indeed, according to some surveys, American children are more likely to recognize Mario than Mickey Mouse!1

Even as late as 1988, three years after its launch, Nintendo was still apparently struggling to meet consumer demand for its best-selling console, easily outselling all the other toys during each Christmas season.2 It may seem odd today to liken a game console to children’s toys like GI Joe or Transformers action figures, but this was precisely Nintendo’s strategy. At a time when most major retailers were sensibly wary of videogames and consoles like the Atari VCS and ColecoVision after the Great Videogame Crash, Nintendo worked hard to market their product as a toy rather than a game console, heavily promoting their “Robotic Operating Buddy” (ROB) and Zapper light gun in their packaging and advertisements. Indeed, the first of Nintendo’s television commercials in America only showed these devices; Mario is nowhere to be seen! According to this rather misleading commercial, ROB will “help you tackle even the toughest challenge,” even though in actuality he was used in only two rather underwhelming games, Gyromite and Stack-Up. Some buddy he turned out to be! As we’ll see, however, perhaps the challenge the commercial was talking about was getting the NES into stores in the first place. Even Electronic Games magazine was skeptical, writing in their March 1985 issue that “considering that the videogame market in America has virtually disappeared, [launching a console now] could be a miscalculation on Nintendo’s part.”3

The cover of the manual for the Control Deck, showing the Nintendo Entertainment System with its standard controllers.

Bionic Commando on the FCEUX emulator.

Bionic Commando (1988, Capcom)

Based loosely on an arcade game by the same name, Bionic Commando for the NES is a platform game with a fun hook—and we mean that literally. The character, Ladd Spencer, is a commando whose shtick is a bionic arm with a grappling gun, which he can use to climb and swing. It’s a good thing he has it, too, since (for whatever reason) he is unable to jump. In the original Japanese version, the plot involved Nazism and was steeped with Nazi imagery, all of which was purged for the English localization. Of course, it was the swinging mechanic that grabbed all the attention from gamers and critics, who felt it brought something fresh and original to what was quickly becoming a saturated genre of platform games.

In retrospect, it seems incredible that Nintendo would face such resistance in marketing their console in the US, but there was plenty of pessimism. It certainly didn’t help that the console was initially more expensive than a ColecoVision, with cartridges costing five times as much.4 Nevertheless, by 1987, the upstart had systems and games in over 12,000 US retail outlets and had seized 70% of the market.5

Nintendo is a very old company, with roots going back to 1889. Back then, it made playing cards before diversifying into taxis and “love hotels” in the 1960s. “Love hotels,” by the way, are hourly-rate hotels where we can assume the guests did not play cards. In 1966, Nintendo unveiled the Ultra Hand into the Japanese toy market. This simple toy, which was a sort of pick-up tool, was designed by Gunpei Yokoi, the company’s janitor. The then president of Nintendo, Hiroshi Yamauchi, saw Yokoi playing with the contraption, which he’d whipped up in his free time. Instead of punishing or firing him for goofing off, Yamauchi promoted Yokoi on the spot and demanded he develop his toy into a product line before Christmas. Yamauchi’s instincts were spot-on; the product was the first of many sweeping successes Yokoi would bring to the company. The former janitor would go on to design several key products for Nintendo, including the Game & Watch handhelds, the famous D-pad style game controller, and the Game Boy. The Ultra Hand may also have inspired ROB, which he originally designed in 1985 as the “Family Computer Robot.” As we’ll see, ROB will play a key role in Nintendo’s takeover of the American videogames market.

Nintendo was quick to see the promise of videogames. As early as 1974, Nintendo leapt at the opportunity to distribute the Magnavox Odyssey in Japan. Nintendo soon began making their own gaming hardware, beginning with a set of five dedicated games, the Color TV-Game series, based on PONG, Breakout, and arcade racing games. In addition to console games, Nintendo was soon producing machines for the arcade, including EVR Race in 1975 and, more famously, Donkey Kong in 1981, which changed everything.

Castlevania on the FCEUX emulator.

Castlevania (1986, Konami)

Castlevania is a side-scrolling platformer with a dark, Gothic theme. The player controls Simon Belmont, a vampire hunter with a penchant for bullwhips, which he can use to kill bats, pumas, ghosts, and other creatures, as well as burst candelabra to get the goodies underneath. He also must face off against horror-themed bosses like Frankenstein’s monster and mummies. The game launched a franchise that is still ongoing.

In 1980 Nintendo rolled out Yokoi’s famous Game & Watch series of handhelds, which played a single game on an LCD screen. They were another breakthrough product for Nintendo. The inspiration for the product came when Yokoi was riding the bullet train back home one evening and noticed a man playing with a pocket calculator to pass the time. If a boring old calculator could be diverting, Yokoi wondered, what about a similar device that could actually play games? Since a joystick was impractical, Yokoi designed the D-pad that has now become standard on nearly every game controller. Eventually 59 titles were released, including Donkey Kong and Balloon Fight.

Powered up by the encouraging success of Game & Watch and other videogaming ventures, Nintendo decided to up the ante with a full-on game console. The goal was to create a system that would be cheap, but with enough of a lead in technology to keep it ahead of the competition for at least a year. The result was the “Family Computer,” better known as the “Famicom,” which Nintendo released in Japan in 1983, launching it with the ever-popular Donkey Kong and Popeye arcade games. Unfortunately, a design fault in these systems led to a recall that cost the company millions. Even with this loss, the Famicom clobbered its competition, Sega’s SG-1000, which had been released in Japan on the same day as the Famicom. This rivalry with Sega would continue for several generations of consoles, reaching its highest pitch with the release of the Sega Genesis (see Chapter 2.3).

Image of the 2011 Club Nintendo exclusive recreation of the very first Game & Watch, Ball. Nintendo would go on to produce many electronic devices like this, including some with dual screens, tabletops, and even watches.

Nintendo wasted little time in adapting their Famicom system for American distribution. They originally approached Atari to manufacture and distribute their system, which was to be renamed the “Nintendo Enhanced Video System.” However, a complex series of events at the 1983 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) scuttled the deal. Atari had purchased from Nintendo the exclusive rights to make Donkey Kong ports for home computers, but Ray Kassar, the CEO of Atari at the time, saw the game running on a Coleco Adam, and felt they had been swindled. The case really gets at the ambiguity surrounding what constitutes a console versus a full computer, since the Adam is basically an add-on for the ColecoVision (see Chapter 1.8). In any case, the events apparently soured relations enough to send the deal into limbo, and it wasn’t the last time the two videogame giants would be at odds.

Deciding to go it alone, Nintendo approached several major retailers, but were turned away. By this point, the Great Videogame Crash had brought the North American games industry to a grinding halt, with bargain bins all over the country filled to the brim with cut-rate cartridges and failed consoles. The company’s first thought was to follow the lead of Coleco and others by turning their system into a full computer, with a datasette, keyboard, and BASIC programming cartridge. In a move prescient of their later Wii console, all of the system’s components were wireless. However, when they unveiled this “Advanced Video System,” or AVS, at the 1984 CES, no one was impressed with either the keyboard or the wireless capability. Once again, Nintendo had failed.

A year later, however, Nintendo returned to CES with a barebones unit they were now calling the “Nintendo Entertainment System,” or NES. The keyboard, datasette, and wireless functionality were gone. In a move to distinguish it from other consoles, the cartridge slot sported a loading chamber that kept cartridges hidden from view when inserted. Instead of pushing the unit as a home computer, Nintendo sold it as a toy, and Yokoi’s cutesy ROB played a key role in selling that perception. To further placate the skepticism of retailers, Nintendo offered to do their store setups and marketing, and even give them a three-month credit on the merchandise.6 Any unsold units could be returned to Nintendo for a full refund. Fortunately, Nintendo was never asked to make good on that promise.

Contra on the FCEUX emulator.

Contra (1988, Konami)

The game that would come to define the “run-’n’-gun” genre began as a 1987 coin-op arcade game, before the developer decided to port it for various home computers and consoles. They produced the 1988 NES version in-house, making some subtle and not-so-subtle changes, including removing the time limit of the arcade version. Gamers loved the tight controls and fast pace, as well as the polished levels and two-player functionality. This was also the game that helped make the “Konami Code” a meme among gamers.

The NES was an unbelievable success in America just as the Famicom had been in Japan. At least 34 million units were sold in the US, with 61.91 million sold worldwide.7 In five years, the NES had more active users in America than any previous console, and had replaced Toyota as Japan’s most profitable corporation. By 1989, NES units were in over 20 million American homes. No one was declaring the death of the videogames industry any more. Indeed, as one reporter for The New York Times put it rather begrudgingly, “It takes work to avoid Nintendo. There are Nintendo television shows, a cereal and a magazine, as well as T-shirts, sweatshirts hats, pins, pajamas, beach towels and school lunch boxes.”8 Now everyone knew that videogames were here to stay.

What made Nintendo and the NES so mind-bogglingly successful? There are at least three key factors: designing great games, regulating the supply of consoles and cartridges, and patenting a “lockout” system to maximize licensing fees from third-party game developers.

First off, Nintendo had Shigeru Miyamoto at their disposal. An artist rather than a programmer by training, Miyamoto’s game designs were radically fresh and different from those of his rivals, and emphasized bright and cheerful aesthetics that delighted gamers of all ages. Miyamoto established a name for himself with Donkey Kong, the 1981 Nintendo arcade game that also introduced us to Mario (though he was a carpenter called “Jumpman” in that game) and the classic rescue-the-damsel theme. Miyamoto built on many of the gameplay mechanics of Donkey Kong to make Mario Bros., a 1983 arcade game that added several key innovations to the genre. The best was the ability to defeat enemies (turtles) by hitting the platforms beneath them, flipping them on their backs. At this point, Mario can jump on them from above, squashing them. The game also sports the familiar pipes and coins that have become staples in the series. As impressive as Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. were, however, the brilliant Miyamoto was just getting started.

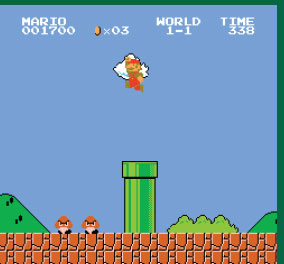

Super Mario Bros. is the game that established Nintendo as a household name. Screenshot taken with the FCEUX emulator.

In 1985, Miyamoto and Takashi “Ten Ten” Tezuka created Super Mario Bros. The game was indeed a super upgrade to the original, with a partial side-scrolling feature that allowed for a much larger game world. Mario (or Luigi) can also receive a variety of fun power-ups, especially a magic mushroom that enlarges them. It is also possible to destroy blocks by hitting them from below, which allows for some fun tactics as well as locations to hide bonus items. Perhaps what makes the game so compelling, however, is the fine attention to detail and precision. The game looks, sounds, and feels great, with a degree of spit and polish seldom seen from other game studios.

A page from the first issue of Nintendo Power, July/August 1988, showing gameplay strategy for The Legend of Zelda’s first level. Nintendo Power was one of the most popular and longest running of the official console magazines, lasting until its final December 2012 issue.

As if Super Mario Bros. wasn’t enough to make Nintendo a household name, Miyamoto and Ten Ten followed up in 1986 with The Legend of Zelda, an “action-adventure” game that allowed even greater exploration and immersion than Super Mario Bros. Originally released for the Japanese-only Famicom Disk System, by the time it reached the US the following year, it had found its way onto one of the first cartridges with battery-backed memory for saved games. Eventually selling well over 50 million copies, Link is second only to Mario in terms of popularity among Nintendo’s legions of fans.

Super Mario Bros. was followed by two more hit sequels in the US. Of these, Super Mario Bros. 3, which was released in the US in 1990, is by far the best-selling—it was even listed in the 2008 Guinness Book of World Records as the best-selling game of all time (that wasn’t bundled with a system). Needless to say, Nintendo owes a great deal of its success to the design genius of Shigeru Miyamoto.

However, great games aren’t the only part of the story. Nintendo had learned from the court battles fought by Atari and its rivals about the perils and opportunities of licensing. The second factor was American operations manager Peter Main, a former marketer for Colgate toothpaste. Despite his lack of experience with the videogame industry, Main recognized several of the NES’s key advantages, including longer gameplay sessions. The older generation had specialized in what we’d call “casual” games today; games intended to be played for minutes rather than hours. After a half hour or so, you either finished the game or got bored and quit. The reason, of course, is that many of these games were based on arcade games, which were designed that way for economic reasons—you don’t make money if someone can play for hours on a single quarter! Main realized, however, that games like the role-playing classic Dragon Warrior (1989), which can take up to 200 hours to complete, were the future.

Main also knew how to manipulate the market, limiting production runs to keep demand high without saturation. To this end, the company only partially filled retailer orders for games and systems. In 1988, Nintendo only shipped 33 of the 45 million cartridges ordered by retailers.9 It was a strategy that infuriated these same retailers, but it only made Junior (and his frustrated parents) scream more loudly for the latest NES games at Christmas time.

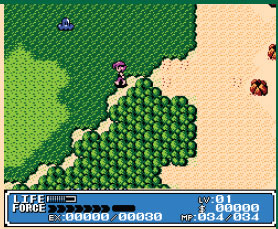

Crystalis on the FCEUX emulator.

Crystalis (1990, SNK)

Although lesser known than Legend of Zelda, Crystalis is a solid action-RPG game that has become a cult classic among aficionados of the genre. Unlike Link, the hero of this game can move diagonally, but the plot is similar in structure—find the four elemental Swords of Water, Thunder, Fire, and Wind, and combine them to form the mighty sword Crystalis and defeat the despicable Emperor Draygon. There’s also more role-playing in this game and its dialog. Allegedly influenced by the Hayao Miyazaki classic Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Crystalis was called God Slayer: Sonata of the Far-Away Sky in Japan. The excellent music greatly enhances the mood. Unfortunately, a later version released for the Game Boy Color was inferior to its predecessor in almost every way. Stick to the original.

Nintendo did not want to allow other companies to make games for their system without paying a hefty licensing fee. To this end, they ingeniously created and patented the 10NES lockout system. Any cartridge that did not contain a special microchip would not run on their system. Thanks to patent protection, only Nintendo could legally make these chips, and their control of a patent was much more powerful in court than a copyright would have been. This also allowed Nintendo to prevent games from being released that didn’t measure up to their strict quality and moral standards. More importantly, it allowed them to make a profit from every game sold, regardless of where it originated.

In 1987, an embattled Atari had split off its console game publishing division, relabeling it “Tengen.” They then tried and failed to get a better licensing deal from Nintendo. Scorned by Nintendo’s prompt rejection, Tengen then asked the US Copyright office for the details on the 10NES, allegedly using this information to build their own chip called the Rabbit. As if to rub it in, Randy Broweleit, a marketing official for Atari, emphasized how the new Tengen packaging would sport a “Made in USA” logo to distinguish them from Nintendo’s authorized games. To no one’s surprise, Nintendo promptly sued. Although Atari/Tengen had sympathy in some political circles who agreed that Nintendo’s practice felt like it was stifling competition unfairly, the point became moot when the two settled out of court.

Perhaps the most infamous court battle between Atari and Nintendo took place in 1989. By then, the Tetris craze was gaining rapid momentum, and everyone knew that whoever owned the rights to the NES version would make a huge fortune. Unfortunately, the copyrights were owned by the Soviet Union government, who made a real mess out of licensing. In a convoluted series of arrangements, Atari ended up with the rights to make the arcade version, whereas Nintendo was given the rights for handheld versions and non-Japanese console versions (Namco had the Japanese console rights). Atari, acting under Tengen, released an NES version anyway, an act that naturally erupted a long and costly legal response from Nintendo. Again, the issue came down to whether a game system, in this case the NES, was a console or a computer. Eventually, Tengen lost the case, and was forced to recall their version—which many fans considered superior to Nintendo’s.

Although gamers loved Nintendo and their games and consoles, the company was becoming just as well known for its heavy-handedness with retailers. In 1991, they lost a price-fixing case. To keep retailers from discounting sales of their system, Nintendo had threatened to cut off their supply. The Federal Trade Commission called it a “pernicious practice” and wanted to make an example of the company, who had to cover the court costs as well as send $5 coupons to anyone who had purchased their system between 1988 and 1990.

Despite these and other setbacks, however, the NES remained the dominant console of its generation, lasting well into the 1990s. At the time of its American release in late 1985, the NES didn’t have much serious competition from other consoles. By 1988, however, parents shopping in the Sears Wish Book could choose among an $89 Atari 7800, a $109 Sega Master System ($149.99 for the version with “SegaScope 3D” glasses),10 or a $99 Nintendo Action Set (which included everything but ROB). It’s telling, of course, that the catalog dedicates a full three pages to Nintendo and its games, whereas Atari and Sega get only a page each. While fans of these platforms still debate their relative strengths and weaknesses, there’s no doubt that Nintendo had the decisive lead.

Nintendo made its last NES in August of 1995. By that point, their Super NES had been available for four years and had long since replaced its older brother as the king of Nintendo consoles.

Duck Tales on the FCEUX emulator.

DuckTales (1989, Capcom)

What kid growing up in the 1980s didn’t love Disney’s DuckTales cartoon? We bet you can sing the catchy theme music even today. Capcom did a great job adapting the property into a fun and satisfying platform game, with an irresistibly cutesy aesthetic—this is definitely no duck-blur. Considered the gold-standard of NES cartoon-based games, DuckTales is a solid platform game for fans of the television series or just platform games in general. DuckTales Remastered, which remade the game in high definition, was released in 2013 for the Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, and Wii U. Ooh ooh!

Today it may be hard for some to picture a videogames industry without the heavy influence of Nintendo, Sega, and other Japanese companies. Jack Tramiel of Commodore (and later Atari) had always feared a Japanese takeover of the home computer market with the MSX standard, but that never occurred. The real invasion took place in the console market, where Nintendo, Sega, and eventually Sony replaced Atari, Mattel, and Coleco as the key players in the console market. The result of this heavy penetration of Japanese technology and games has left an indelible impression on multiple generations of American gamers, many of whom grew up playing Japanese, rather than American-made, games. With the sole exception of Tetris, the top ten best-selling games for the system were all made in Japan. Although American gamers continue to clamor for the latest Japanese games, the feeling is far from mutual. Even major Western franchises like Halo and Call of Duty are played by only a small fraction of Japanese gamers.11

All in all, the NES is without question among the most important and influential game consoles of all time. While a lot of this impact comes from the stellar quality and variety of its game library, Nintendo’s shrewd business strategies paid off royally, allowing them to placate skeptical retailers in America. They had learned from Atari and Coleco and were able to capitalize on their successes while avoiding their mistakes. Perhaps more importantly from a cultural perspective, the NES helped make Japan the undisputed leader of the worldwide console market, a position the nation still enjoys today. And it owes it all to an artist, a janitor, and a toothpaste salesman.

Notable Accessories

The NES enjoyed some of the most memorable third-party accessories and peripherals of any other platform. Probably the most famous (or infamous!) of these is the Power Glove, which was featured in The Wizard, a 1989 movie/Nintendo promotional vehicle starring Fred Savage. Manufactured by Mattel, the Power Glove may have looked cool, but fell far short of its overblown marketing claims of “revolutionizing the video game interface.” In reality, the Power Glove was a clunky and imprecise way to control most games, and certainly in no way superior to the default game pads shipped with the system. Today it ranks on several lists of the worst game controllers ever.

The Power Glove, seen here about to grab ROB, was mostly ineffective as a game controller, but it looks so bad. Not pictured is the sensor array that needed to be placed around the television for proper tracking of the glove. The dust on the glove and discoloration of the robot’s plastic are two of the pitfalls of modern-day collecting.

Another seemingly innovative controller called the U-Force was introduced by Broderbund in 1989. This time, there was no glove; only infrared beams that tried to interpret hand movements. Unfortunately, much like the Power Glove, the concept was much cooler than the execution could hope to be for the technology of the time.

A slightly more successful accessory was the Power Pad, which resembles a Twister mat but with panels reminiscent of a Dance Dance Revolution game. Made by Bandai, it was marketed primarily as a way to curb the growing obesity epidemic. Most of the handful of games made for the Power Pad were related to athletics or exercise, such as Athletic World and Dance Aerobics.

Nintendo was impressed enough with the product’s potential to take over its distribution and bundle it as part of their Power Set.

The NES Advantage was an arcade-style joystick designed to lie on a flat surface. Considered among the best accessories for the system, the NES Advantage is great for playing arcade ports and controlling the Statue of Liberty.12

Software Toolworks also released a musical keyboard for the NES called the Miracle Piano Teaching System. Intended to help kids learn to play the piano, the system was too expensive ($500) to generate enough sales to keep it viable. Still, what could be more fun than playing the correct note to shoot down a duck?

There were plenty of other accessories available, including a wide variety of controllers, light guns, and a cavalcade of non-game merchandise ranging from bed sheets to cereal.

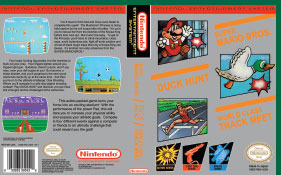

This modern-day game box mock-up shows the three games—Super Mario Bros., Duck Hunt, and World Class Track Meet—that were featured in the Nintendo Entertainment System Power Set, which included two gamepads, the Zapper, and the double-sided Power Pad. Nintendo would make the NES the centerpiece of a variety of bundles over the years.

Mega Man on the FCEUX emulator.

Mega Man (1987, Capcom)

The NES was a haven for great platform games, and Mega Man is widely ranked among the best despite its difficulty. Its six-man development team had worked insatiably to produce one of the most polished and artistic games of its type. Unfortunately, some hideously bad cover art on the North American box may have played a role in its disappointing sales—several prominent publications have ranked it the worst game cover of all time! Still, the game was successful enough to warrant a sequel, and eventually it became one of Capcom’s most successful franchises.

The NES featured a Ricoh RP2A03 8-bit 6502 microprocessor that ran up to 1.7 MHz, with 2K of memory. The display was capable of 256 × 240 resolution with 54 simultaneous colors, although most games were in 256 × 224 to compensate for older televisions. The system supported up to 64 sprites. The NES’s audio capabilities featured four channels of mono sound: two for square waves, one for a triangle wave, and a noise generator. There were two ports for controllers. The standard controllers had an eight-way thumb pad, two action buttons, and a start and select button. Many gamers, particularly adults, found the small, boxy controllers awkward or even painful to use for extended periods. Nevertheless, due to its ubiquity on Japanese systems, it did not take long for gamepads to replace joysticks as the industry standard for console controllers.

One of the design goals of the NES was that it should be at least a year ahead of the competition in terms of technology, a goal it mostly met. One of its major advantages was hardware scrolling with support for tile-mapping, which was used to superb effect in games such as Metroid. Although the 2K of memory might seem like a severe limitation, Nintendo wisely designed the system so that cartridges could have their own RAM, expanding the available memory of the system. The Sega Master System, released in American in 1986, was largely technically superior. By that time, however, Nintendo had achieved enough momentum and brand recognition to prevent both the Sega Master System and Atari’s 7800 from seriously threatening its dominance. Then, as now, most gamers will choose the system with the best and most abundant game library, not the one with the most impressive technical specs.

The NES did have a technological ace-in-the-hole, however, and that was the ability for the console to leverage special chips placed inside cartridges to extend the platform’s capabilities. The most famous of these was Nintendo’s MMC-series of chips, with for instance the MMC1, used in games like The Legend of Zelda and Metroid, allowing for saved games, better multidirectional scrolling, and improved memory switching.

Metroid on the FCEUX emulator.

Metroid (1986, Nintendo)

Metroid is one of the best games for the NES and remains one of the most engaging side-scrolling platform games of all time. Players take control of a dude in a suit named Samus (hey, no spoilers here!), a bounty hunter who must make his way through a vast fortress planet of Zebes while battling a wide assortment of enemies. What makes the gameplay stand out, however, are the many power-ups you can find for your suit, such as high jump boots and ice beams. Far more than just weapon upgrades, these items allow Samus to explore new parts of the map that were inaccessible before. Another good reason to check out this game is the amazing musical score by Hirokazu Tanaka, which really sets a profoundly somber mood.

No discussion of the NES’s hardware would be complete without mention of the infamous issue with its cartridge slot. These were caused by the 10NES lockout chip discussed above, which required a constant connection. Over time, the connectors would loosen or wear out, impeding or blocking the all-important connection. To temporarily “fix” the problem, gamers would blow into the cartridge connectors, slap it around, or even lick it! Needless to say, sometimes these “solutions” only led to more problems. Owners could take their system to a “Nintendo Authorized Repair Center,” which were basically just shops who had agreed to pay the company a large fee to qualify for replacement parts.

In 1993, Nintendo released the NES-101, called the “Nintendo Entertainment System Control Deck.” This was a much smaller version of the system usually referred to as “the top-loader,” since the new design eliminated the cartridge garage in favor of a slot on top of the unit. It’s also quite a bit smaller, though it did lose its composite audio-video out in favor of only RF output. The system included one “Dogbone” controller, so named because of its shape, with rounded edges rather than the harsh corners of the original. Retailing for $49.99 in the US, the NES-101 was only in production for five months. By this point, anyone who was serious about gaming had moved on to a Sega Genesis or Super NES. However, the limited production run, as well as some key advantages—such as its redesigned cartridge slot and lack of a lockout chip—make it a great collector’s item today, even with the less desirable restriction on its audio-video output.

Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!! on the FCEUX emulator.

Mike Tyson’s Punch Out!! (1987, Nintendo)

It’s been over 25 years since Little Mac, the 17-year-old boxer from the Bronx, threw his first uppercut at a 21-year-old Mike Tyson in this loose interpretation of the arcade games. Still, who has forgotten about Glass Joe and Doc Louis? This seminal boxing game is ranked by many among the best games on the platform, and even if you have zero interest in boxing, you don’t want to miss this one. For one thing, the designers preferred arcade fun over realism, and the goofy, cartoony graphics are much more humorous than gory. Nintendo lucked out by licensing Mike Tyson’s likeness for a mere $50,000 for three years. It’s a good thing they signed the contract just before he became the World Boxing Council heavyweight champion in a famous fight against Trever Berbick. After the three-year contract expired, Nintendo rebranded the game as Punch-Out!!, renaming the controversial Tyson’s in-game character to Mr. Dream. With stellar sales and critical reviews, Punch-Out!! was a discombobulatingly devastating part of the NES’s game lineup.

The Nintendo Entertainment System Community Then and Now

In its heyday in the mid- to late 1980s, the NES enjoyed a user base of over 30 million in the US alone. The appeal was so great that one reporter wrote that “for boys in this country between the ages of 8 and 15, not having a Nintendo is like not having a baseball bat.”13 Shortly after, an 11-year-old girl wrote back in response to the article, objecting to the term “boys” in that statement. According to her, “Just as many female adolescents like Nintendo as males do.”14 She could have added that the appeal was just as strong for adults as well, many of whom enjoyed playing games like Duck Hunt as much as their children. The systems were also popular at colleges, where students could pool their money to buy and share new games and compete for high scores. Much like the Wii 20 years later, the NES enjoyed nearly universal appeal, with a huge variety of games suitable for all ages.

By far the most popular magazine for the NES was Nintendo Power, which began publication in 1988. The magazine, an official Nintendo publication, was focused mostly on game tips and reviews, including colorful maps for popular games like The Legend of Zelda. Before Nintendo Power, Nintendo had offered a free printed publication as part of its “Nintendo Fun Club.” This is the club referenced in Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!!, when Little Mac’s trainer advises him to join the Nintendo Fun Club to learn how to win more matches.

Naturally, not everyone was pleased with Nintendo’s success. Besides the understandable protests from retailers and rivals concerning the company’s monopolistic tendencies, there were plenty of silly claims about the systems causing obesity, addiction, or even physical harm. The latter were usually cases of so-called “Nintendo thumb,” or blisters or other ailments brought on by excessive use of a D-pad. There were also the usual litany of complaints about videogame addiction and possible links to violence, though Nintendo’s strict censorship policies kept these complaints to a minimum.

Today, NES enthusiasts congregate in large numbers online. Probably the best place to get started is YouTube, where fans exchange gameplay videos, reviews, and discussions of their favorite games and accessories. Speed runs, in which players try to complete a game in the shortest possible time, have become a staple, with some truly remarkable performances by highly skilled players. Freddy Anderson’s speed run of Super Mario Bros. 3 is particularly impressive, clocking in at only ten minutes, 48 seconds.

Blade Buster is a homebrew project with great graphics and animation. Screenshot taken with the FCEUX emulator.

The NES’s distinctive sound hardware inspired countless memorable soundtracks. Many of these have been remixed by some truly talented artists, such as the bands Armcannon and Metroid Metal. Indeed, a whole genre called “Nintendocore” has grown up around the idea of fusing modern genres with music and sounds from the NES and Game Boy. The Advantage, Power Glove, Daniel Tidwell, and The Minibosses are great examples.

One of the best sites for modern NES homebrew enthusiasts is www.nesworld.com. The site has loads of information for collectors, gamers, and history buffs alike. Some of the best NES homebrew includes Kent Hansen and Andreas Pedersen’s D-Pad Hero, which is a fun take on Guitar Hero for the NES, and High Level Challenge’s Blade Buster, a shoot-’em-up that really demonstrates the latent audiovisual potential of the platform. There is also a lively discussion forum on the site with hundreds of active members. Other popular forums for NES fans are at http://gonintendo.com, http://nintendoage.com, and http://nesforums.com.

Collecting for the Nintendo Entertainment System

Because there were so many units sold and distributed widely, it’s easy and relatively inexpensive to find working NES units in good condition on online auction sites or retrogaming shops. Unless you’re concerned about historical accuracy, it’s probably a good idea to get a unit with a refurbished pin connector and disabled lockout chip. Although generally pricier, the NES-101 is a good system for collecting as well, especially since it’s more reliable and has no lockout system to worry about, but you may wish to consider an upgrade to its RF output.

If you don’t care about owning actual Nintendo hardware, you might spring instead for a clone gaming system, such as those from Retro-Bit or Hyperkin. The accuracy and reliability of these knock-offs vary widely, so you should take time to study the reviews carefully before making a purchase. One major advantage of these systems is the ability to run games from multiple systems on one unit, an important consideration for those with limited space.

The cost of acquiring game cartridges varies, of course, depending on the relative obscurity and desirability of each title. Many NES owners discarded the boxes and manuals that came with their games, so copies with intact packaging usually cost quite a bit more than loose cartridges.

Since Nintendo’s patents have expired on its NES technology, many quality clones, both handheld and console, are now available for purchase. Shown here is the prototype version of perhaps one of the most interesting of such clone systems, Hyperkin’s RetroN 5, which not only plays Famicom and NES cartridges, but also those for the Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis, and Game Boy Advance, among others.

There are several extremely rare and sought-after NES cartridges that any hardcore collector would love to own. Stadium Events, a game for the Power Pad that Nintendo quickly bought out from Bandai and rereleased as World Class Track Meet, is said to have only 200 copies still around. An eBay auction in 2010 for a sealed copy broke records by reaching $41,300! Another high-ticket item is Nintendo World Championships Gold, a promotional item for the 1990 “Nintendo World Championship.” These can command tens of thousands of dollars. An alternative to these high priced originals are reproductions from companies like Retrozone, who also stock one of the several types of flash cartridges available that allow transferring ROM images for play on a real system, as well as homebrew game development.

Ninja Gaiden on the FCEUX emulator.

Ninja Gaiden (1988, Tecmo)

Nostalgic gamers like to bemoan the state of modern gaming, in which no real skill or patience is required to beat a game. Clearly, they wouldn’t last ten seconds with a real challenge like Ninja Gaiden. Celebrated for its intense difficulty, Ninja Gaiden is another side-scrolling platformer, but this time with a ninja named Ryu battling his way through cities, jungles, castles, and snow. It also featured some awesome cut-scenes inspired by anime. Not that you got to see very many—did we mention this game required actual ninja skills to win?

For the most dedicated of collectors, there is the whole world of Japanese Famicom hardware, accessories, and software to explore. While emulation is the safest, most inexpensive route to investigating some of these Japanese releases, there’s nothing quite like using the actual items little seen or known outside of their home country. There are even a few dozen or so releases exclusive to the European PAL television format that generally work on NES-compatible systems that don’t have a lockout chip. Differences in CPU speed and display formats may cause a few peculiarities in play, however, so if you favor accuracy with these releases, either get a PAL-based system or stick to emulation.

Nintendo’s earlier release of the Famicom and interesting sublicensing, add-ons, and software variations that were never released outside of Japan make it an interesting, if challenging, platform for the would-be collector. Generally speaking, with a simple pin adapter, most Famicom and NES cartridges are cross-compatible, even if many of the other items aren’t.

Emulating the Nintendo Entertainment System

Emulation for the NES is generally considered 100 percent accurate, and ROM images for just about every game are freely available online. The two most popular choices for emulators are FCEUX and Nestopia. Ports of these excellent and straightforward emulators are available for Windows, Macintosh, and Linux. Sites like http://virtualnes.com will even let you play many NES games right in your web browser.

Naturally, playing these games will be more authentic with the proper controller. Amazon and ThinkGeek offer USB controllers that closely resemble the original NES controllers. Ranging from $7–30, they are a cheap and easy way to duplicate the feel of an NES game without the actual hardware. Other options include USB adapters for the original controllers themselves. Using one of these definitely beats trying to play Contra with a keyboard!

FCEUX is a modern NES emulator for the PC and other platforms. The emulator is shown here playing Double Dragon.

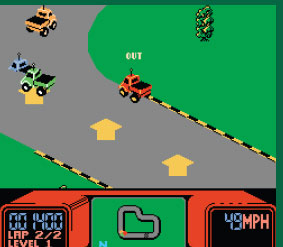

RC Pro-Am on the FCEUX emulator.

RC Pro-Am (1988, Rare)

Well before Super Mario Kart on the Super NES popularized the kart-racing genre, there was this little gem from Rare, an English company that was one of the few non-Japanese developers to realize great success on the platform. The novelty of this game was racing in remote-controlled cars, but the fun came in the form of power-ups like missiles and bombs, along with a fair share of hazards. Its modified isometric view was a refreshing change from the first-person view that was the standard of the day. Although it lacks the multiplayer mode found in its 1992 sequel, RC Pro-Am II, the original remains one of the most fun racing games for the system.

Of course, Nintendo and other companies have digitally rereleased large portions of their NES library for their later systems, like the 3DS and Wii U. Many unofficial emulators are also available on mobile platforms, like Android, allowing play on various smartphone, tablet, and console form factors.

1 This oft-stated claim is based on data compiled by the Marketing Evaluations company, who generates “Q-ratings” of consumer appeal for personalities, characters, and brands.

2 According to an article by Joseph Pereira in the Wall Street Journal, November 22, 1988, retailers demanded 1.5 million NES units in that year alone. Total console and cartridge sales for that year totaled $850 million.

3 Steve Bloom, “Hotline,” Electronic Games, March 1985.

4 According to Bob Davis and Sandra Ward, “Hightech Toys are Hot Again this Year but Biggest Sellers are Repeats of 1984,” Wall Street Journal, December 17, 1985.

5 N. Gross and G. Lewis, “Here Come the Super Mario Bros.,” Business Week, November 9, 1987, p. 138.

6 Worlds of Wonder, the toy company who struck it big in the mid-1980s with Lazer Tag and Teddy Ruxpin, was Nintendo’s initial partner for getting into big box stores. Within a few years, Nintendo would no longer need the company’s assistance, and Worlds of Wonder, like Coleco a few years before it, would be out of business by 1990.

7 According to Nintendo’s own Consolidated Sales Transition by Region charts, available at www.webcitation.org/5nXieXX2B.

8 A.R., “The Games Played for Nintendo’s Sales,” The New York Times, December 21, 1989.

9 A.R., “The Games Played for Nintendo’s Sales,” The New York Times, December 21, 1989.

10 Much like how Nintendo initially relied on Worlds of Wonder, Sega initially relied on Tonka for help breaking into the American retail market.

11 There are many proposed explanations for this imbalance. According to Ryan Winterhalter of http://1up.com, there is a widespread bias among Japanese gamers against Western games. According to Winterhalter, when a “high profile JRPG maker” played Bioshock, he threw down the controller after less than a minute, claiming the game “felt cheap.”

12 As seen in the 1989 movie, Ghostbusters II.

13 D.C., “Nintendo Scores Big,” The New York Times, December 4, 1988.

14 D.S. Margolin, “Nintendo Fans,” The New York Times, January 1, 1989.