History

When Microsoft first announced its plans to enter the console market at the Game Developers Conference in 2000, many people thought the company had lost its way. There were three good reasons to doubt that even the richest company in the world could bully its way into the console market: Microsoft’s reputation as a business-oriented company, Japan’s undisputed dominance of the console industry, and a long-standing prejudice by many console fans against PCs.

First of all, while Microsoft always dabbled in games publishing, they were primarily known as a serious, business-centric corporation, making the bulk of its money from operating systems and productivity software. In 1996, their much hipper rival Apple had tried to enter the console market with their Pippin—a multimedia console that had failed miserably. Sure, Microsoft had deeper pockets than Apple, but would it really be willing to invest the billions of dollars it would take to convince their skeptics that they really understood gaming? Certainly, Microsoft’s past experiments in the console space, like in 1992 with the Tandy Memorex Visual Information System (VIS) multimedia console (which used a version of Windows 3.1), and in 1998 with Sega’s Dreamcast (which used Windows CE as one of its operating systems)1, didn’t exactly instill any confidence either.

Burnout 3: Takedown.

Burnout 3: Takedown (2004, Criterion Studios)

In many car racing games, the objective is to avoid smashing into things. This game reverses that mechanic, rewarding players for causing as much mayhem as possible. The more damage you do, the more cars you unlock—up to 70. There are also 40 tracks to play on. You could also race with up to six others online. The game received several awards and accolades, and most critics agree that the arcade-style gameplay will appeal even to gamers who dislike traditional racing games. If you don’t care for the soundtrack, which features over 40 licensed tracks, you can create your own mix.

Secondly, after the Great Videogame Crash, the bulk of the console industry moved to Japan, where it had dominated from ever since. For many years, Nintendo ruled, but the upstart Sony had wrestled control away from them and their rival Sega with the PlayStation. The PlayStation was a juggernaut, and had already lured away several prominent Windows game developers. Sony had announced its successor, the PlayStation 2, back in March 1999, and it would hit American shores like a tsunami in October 2000, wowing everyone with its promise of amazing graphics and processing power. Even if Microsoft could somehow design a system that was technically superior to the PS2, would gamers and developers pay it any attention? After all, Japanese gamers tend to be fiercely loyal to companies from their own country.2 Even if Microsoft could get a foothold in America, as a non-Japanese company, they would struggle with this cultural bias, hampering their ability to compete globally. While many gamers were curious about what Microsoft was up to, the smart money was on Sony and Japan.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, few gamers were interested in what they assumed would be a boring Windows PC in console clothing. Then as now, many gamers preferred a device dedicated solely to gaming. Although several manufacturers over the years have tried to blur the boundary, the results have seldom been good.3

The story of the Xbox begins in 1998, when four men—Kevin Bachus, Seamus Blackley, Otto Berkes, and Ten Hase met secretly to take apart some Dell laptops. Their idea was to study the laptop’s components and see if they could come up with a prototype for a Windows-based game console. When their “DirectX Box” prototype was ready, they brought it to Ed Fries, head of Microsoft’s gaming division. Fries liked the idea, particularly its reliance on Windows and DirectX, which would make it a snap for Windows game developers to make the transition to console development.

The original Xbox was dismissed by some gamers as a PC masquerading as a console, but, in reality, its operating system and hardware components were highly customized for gaming.

It was time to pitch the idea at a staff meeting. In proper Microsoft fashion, Hase created a PowerPoint presentation that detailed the team’s vision for a gaming console based on DirectX. Much to Hase’s embarrassment, the staff thought the whole thing was a joke. They felt there was simply no way the team could mass produce such a device at a price that could compete with other consoles. Consoles cost hundreds of dollars; computers cost thousands. What the team had proposed was not only infeasible—it was laughable.

Luckily, Bill Gates had been growing anxious that Sony posed a grave threat to the future of Windows as a gaming platform. At the Game Developer Conference in 1999, Ken Kutaragi, CEO of Sony Entertainment, declared the death of PC gaming in the wake of the new PlayStation 2. “Entertainment content requires an entertainment device,” he said to thunderous applause.4 Gates sensed the tide was turning against PC gaming, and that didn’t bode well for the future of Windows. After all, it was gaming that had been the driving force behind the steady stream of upgraded, yet cheaper components that had made Windows viable in the first place. Without the rapid advances in technology demanded by the gaming industry, we might still be computing with monochrome monitors and internal beepers for sound.

Crimson Skies: High Road to Revenge.

Crimson Skies: High Road to Revenge (2003, FASA Studio)

The first Crimson Skies was released in 2000 for Windows. Set in a memorable alternate reality version of 1937, it was an arcade-inspired flight simulator with a fun role-playing mechanic by FASA (a tabletop role-playing, war game, and board game maker). High Road to Revenge updated the formula and customized the interface for the Xbox controller. In addition to a superb single-player campaign, you could also play with four others (split screen) or up to 16 others using the system link.

Gates asked the DirectX team to survey the situation and report back. They concluded that the PC was likely to maintain its edge in hardware, providing better graphics and processing power than any device Sony could possibly deliver. Furthermore, the price of these advanced components had been steadily dropping due to intense competition. The team argued that they could build a console based on these components at a reasonable price point.

Unlike those at the staff meeting, Gates didn’t laugh at the idea—instead, he asked the team to step up their efforts to build a unit that could compete head-to-head with Sony’s PlayStation 2. He gave them until the end of the year to have the unit ready for retail—which gave them fewer than six months to turn their clunky prototype into something resembling a true gaming console.

The team set out to define what the “console experience” actually meant. They decided that the unit had to boot up immediately, not go through the lengthy startup sequence of a PC. Furthermore, loading a game should be as easy as inserting a disc—not wading through menus and installation procedures. They realized that Windows 2000, which they’d been building their console around, was simply too bulky for their purposes. They needed something much lighter and faster, but still close enough to Windows for PC developers to make the transition easily.

The result was a new gaming operating system based on the Windows 2000 kernel, but heavily customized for speed and efficiency.5 Programming Xbox games would be similar to making games for Windows, with APIs (application programming interfaces) familiar to Windows developers. However, software built for the Xbox would not be directly compatible with Windows PCs.

The team shopped around to get the best deals on a processor and components like the GPU and hard drive. They ended up with an Intel Pentium III CPU and a custom GPU from Nvidia. Since their Windows-based operating system couldn’t run without a hard drive, they included an 8 GB hard disk for internal storage—a first for the console industry. The hard disk would add considerably to the manufacturing cost, but, as we’ll see, it would play a key role in the success of the Xbox.

Gates knew his company needed a major publicity splash to build momentum for the console, so he did something he’d never done before: attend and present at the Game Developer Conference in person. It was there, in San Jose, that Gates first traded his business casuals for the famous X-emblazoned black leather jacket and announced that the era of the Xbox had arrived. Perhaps the jacket alone would have been enough to convince gamers and developers that Microsoft was now cool, but just to be safe, they churned a half billion dollars into marketing for the device.6

Bill Gates (left) donned an X-emblazoned black leather jacket to announce the Xbox at the Game Developer Conference. On the right is Seamus Blackley, one of the Xbox’s designers. www.gdcvault.com/play/1014852/GDC-2000-Opening-Keynote-Bill.

Fable: The Lost Chapters.

Fable (2004, Lionhead Studios)

Long in development, Peter Molyneux’s epic Fable was one of the most ambitious role-playing games ever attempted. The idea was to control a character from cradle to grave, with the character’s appearance altering based on his actions (think The Picture of Dorian Gray). While there was still plenty of combat, the role-playing went much deeper. Other characters in the game will notice and begin to treat the character differently based on his behavior. While critics generally praised the game, Molyneux failed to deliver many of the more intriguing features he promised, including multiplayer options and the ability for the character to marry and have children. Perhaps the most infamous, though, is the “acorn incident,” in which Molyneux boasted that if the character knocks an acorn out of a tree, it’ll eventually grow into a new tree. When the feature failed to appear, he swore it would show up in the sequel—but it wasn’t there, either. Fortunately, what Lionhead was able to deliver was more than enough to please most fans of the genre, and the 2005 release, Fable: The Lost Chapters, enhanced the game significantly. In 2014, Microsoft released Fable Anniversary for the Xbox 360, a remastered version of Fable: The Lost Chapters.

Gates realized, however, that no amount of advertisements could sell a machine without a great software lineup. To that end, Microsoft spent $30 million acquiring a little-known company called Bungee, whose new Halo game would serve as the platform’s premier first-person shooter. The move proved incredibly fortuitous later on, but we should keep in mind that, at the time, first-person shooters were a rarity on consoles. Indeed, to that point, the only console first-person shooter really worth talking about was Rare’s GoldenEye 007 for the Nintendo 64 (see chapter 3.3).

All in all, Microsoft was able to sign on 150 developers, and rapidly sent out 500 development kits to spur their efforts. The only major holdout was Electronic Arts, who was dubious that Microsoft would really have their back if the Xbox flopped in the marketplace. Unlike for Sega and the Dreamcast, they’d eventually come around, but the lack of support from one of the world’s biggest game companies didn’t look promising for the future of the console.

When the console was at last revealed at the Consumer Electronics Show in 2001, Gates was on stage again, this time sharing it with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. The Rock was, as always, a crowd pleaser, and his witty banter with Gates had the place rolling. What was less impressive, though, was the Xbox itself. Journalists criticized the big, clunky unit and its even more awkward controllers that even looked large in The Rock’s hands. Compared to the sleek PlayStation 2 controllers, these looked primitive and monstrous. These would eventually be redesigned, but the first impression was in—and it was bleak.

Microsoft brought on Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson to promote their new console. Their witty banter and antics delighted the crowd at the 2001 Consumer Electronics Show. www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdjAeoqWskU.

Fortunately, the dire predictions or blunt criticisms weren’t enough to scuttle the launch on November 15, 2001. Even at the initial price of $299, the company quickly sold out. It was a much more impressive reception, in fact, than Nintendo had received following its GameCube launch, which had no must-play launch title of its own like Halo: Combat Evolved. In fact, it’s impossible to overstate Halo’s value to Microsoft’s early success.7

In a little under five months after its release, Halo: Combat Evolved broke sales records at the time, with a little over 1 million units sold.8 The success of future console’s launch-day game releases would continue to be compared against the Xbox’s Halo: Combat Evolved for years to come. As IGN’s Ryan McCraffrey would tweet on August 20, 2013, in regards to the Xbox One’s Titanfall (2014), “If @Titanfallgame was a Day One launch title, it would be the killer-est killer app since Halo 1 on OG Xbox. Still a likely system-seller.” While sales for the Xbox were understandably dismal in Japan, it was a hit nearly everywhere else, especially after its first major price drop in April of 2002 helped spur on sales even further.

Although masterpieces like Halo: Combat Evolved, Fable, and Knights of the Old Republic would do much to secure the console’s reputation, the real “killer app” was not a game, but a service: Xbox Live. As we saw in Chapter 3.1, Microsoft had been quick to realize the revolutionary potential of the internet, supporting it in Windows 95 and even creating their own web browser, Internet Explorer. It’s hardly surprising, then, that the Xbox would connect to the internet. At the time, many people still relied on dial-up for internet access, and Sega had opted for a dial-up modem in their Dreamcast (Chapter 3.4). It was a sensible move, considering that only 4.4 percent of American households had broadband in 2000.9 Sony wouldn’t add built-in support for networking until the second iteration of its PlayStation 2, the “Slim,” in 2004. Until then, Play-Station 2 owners had to settle for the $40 Online Adapter and tedious, confusing, title-by-title configurations for online games. Microsoft, however, built an Ethernet port into every Xbox. The advantages were obvious, and they predicted (correctly) that significant broadband adoption was just around the corner.

Ninja Gaiden Black.

Ninja Gaiden Black (2005, Team Ninja)

In 2004, Team Ninja released Ninja Gaiden for the Xbox, a reimagining of the popular arcade game from 1988. The team had planned to release the game for the PS2 instead, but Tomonobu Itagaki, the game’s creator, was impressed with the development kits Microsoft had put together. The decision might well have been part of their larger strategy to target gamers outside of Japan—and they succeeded; the game was a hit everywhere but its mother country. The game offered a third-person “over the shoulder” perspective, and combined the puzzle-solving and exploration of the Zelda series with a mature martial arts theme—with gore and violence aplenty. Ninja Gaiden Black, released a year later, added new foes, cutscenes, and integrated the two “Hurricane” bonus packs from the original game.

The big question, though, was how exactly the company would utilize this high-speed connection. One idea was to use the Xbox’s hard drive to allow game developers to sell additional game content online, such as new levels and maps. This concept, later called DLC for “Downloadable Content,” was soon an industry buzzword. Before, game publishers only made money at the time the game was purchased. Now, they could continue to reap profits long after the game had faded from retail—and recoup some of the losses incurred from the rapidly expanding used game market. It would also allow developers to cheaply “patch” games that had already shipped. Instead of sending out replacement discs, developers could simply upload fixed versions of the troublesome binaries. There was a negative side to this: now publishers could feel better about shipping games with bugs, knowing these could be fixed later with patches.

More famously, though, Xbox Live would become the hub for online competitive gaming, exponentially upping the replay value of games such as Halo and the Call of Duty series. From now on, finishing the single-player campaign was only the start of your “training.” After that, it was time to head online to fight against human opponents from all over the world. Gaming had finally returned to the glorious competitive days of the arcade (see Chapter 1.1).

Xbox Live wasn’t available until November 2002, a full year after the Xbox launch. They charged $49.99 per year for the service, a figure that hasn’t varied much since. Unlike their computer gaming counterparts, Xbox gamers wouldn’t have ready access to a keyboard to chat with other players. To address this limitation, Microsoft insisted that Xbox Live-enabled games would offer voice chat. Inevitably, many users have abused this service, spewing foul language, including sexist and racist rants. Dealing with the problem has been a persistent problem for Microsoft, who has overreacted on a number of occasions—such as deleting user names (called “Gamertags”) like “Gaywood,” which turned out to be legitimate surnames. They also offered the option to mute offensive players and “voice-masking” headsets for gamers that could, in theory, at least, disguise one’s gender or age. In any case, fears over voice chat abuse didn’t stop over 350,000 users from signing on within the first three months. By 2005, they had 2 million.

Xbox Live also gave gamers access to lesser known, “budget-priced” games that weren’t available at retail. This service, called Xbox Live Arcade, featured many titles from 1980s’ arcades, such as Ms. Pac-Man, Joust, and Gauntlet, as well as casual games such as Bejeweled and Bookworm. Microsoft would continue to evolve its online offerings, especially after the release of the 360 in 2005.

As expected, former Windows developers would play a large role in building the Xbox’s games library. To bolster its lineup, Microsoft acquired FASA Studio and made them part of Microsoft Game Studios. This company had established itself with its Mech-franchise, and their Xbox exclusives MechAssault (2002) and Crimson Skies: High Road to Revenge (2003) were praised by critics and sold well. Indeed, IGN singled out MechAssault as the best game for Xbox Live. Bethesda Game Studios was another prominent PC developer who made the move, releasing their open-world role-playing game The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind for Xbox in 2002. Microsoft Game Studios would publish Lionhead Studio’s Fable for the Xbox in 2004, another critically-acclaimed role-playing game. Microsoft acquired Lionhead Studio in 2006. Valve Corporation, which had been founded by former Microsoft employees Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington, brought its mega-hit Counter-Strike to Xbox in 2003, which quickly became a staple of Xbox Live. BioWare’s Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, released in 2003, was another masterpiece, and arguably one of the best Star Wars games ever produced for any system. They’d release Jade Empire in 2005, another great RPG, and introduce their Mass Effect series for the 360. The presence of these and other notable former Windows developers helped distinguish the Xbox from the competition.

Despite all of these innovative games and features, the Xbox was only a minor irritant for Sony, even though their online gaming options were much less unified and convenient as Xbox Live. Microsoft sold over 24 million Xboxes, placing the console just above Nintendo’s Game-Cube at just over 21 million. Both consoles are dwarfed, however, by Sony’s staggering figure of 155 million units for its PlayStation 2, which remains the best-selling console of all time (see Chapter 3.5). As many expected, the Xbox flopped miserably in Japan despite a robust marketing campaign, selling only 2 million units compared to Sony’s 21.10

Oddworld: Stranger’s Wrath (2005, Oddword Inhabitants, Inc.)

Lorne Lanning’s Oddworld series traces its roots back to a seminal platforming/puzzle game from 1997 (see Chapter 3.2). Stranger’s Wrath departs from the formula, using the third-person perspective popularized by the later Zelda games as well as first-person shooter mechanics for combat. You could freely switch between these modes. It was marketed as a “shooter unlike any you’ve seen before,” and they certainly hit the mark. Unlike the cutesy lead characters from the earlier games, this time you play as “The Stranger,” a tough, Clint Eastwood-inspired bounty hunter. Load up your double-barreled crossbow with live ammo, and we mean that literally—your ammo consists of living creatures such as Chippunks and Boombats.

If there was one thing that Microsoft had, it was money, and they knew they had to spend it freely if the Xbox were to survive. Beyond lavishing money on expansive marketing campaigns, they set the retail price of the Xbox so low ($299) they actually lost money on each unit sold. This move was felt necessary to keep them competitive with Sony, who was charging $299 for the PS2. In April of 2002, Microsoft dropped the price by $100, forcing Sony to follow suit two months later. According to some estimates, Microsoft lost $168 for each Xbox sold.11 However, underpricing consoles is a common strategy for manufacturers, who recoup their losses through software and licensing. In the Xbox’s case, licensing fees brought in $7–9 per game sold.12

Perhaps the peak of the original Xbox came in November of 2004, with the long-anticipated release of Bungee’s Halo 2. Within 24 hours, the game had sold 2.5 million copies, making it the most successful product launch in the history of entertainment. Eventually selling over 8 million copies, Halo 2 received near-perfect reviews in major gaming publications and solidified Bungee’s reputation as a master of the genre. While the game’s epic storyline and incredible graphics were lauded by critics, it also introduced a new matchmaking system of playlists and parties with a skill-ranking system. Now, joining online sessions was much faster and friendlier for novices.

The long-anticipated release of Halo 2 was a pivotal event for Bungee and the Xbox as a platform. While the epic single-player campaign was praised by critics, the multiplayer action on Xbox Live was the major draw.

Electronic Arts published its first games for the Xbox in the last few months of 2001. This lineup included its bestselling sports franchises, Madden NFL 2002, NBA Live 2002, and NHL 2002. The company’s strategy was to spread its wares across all major platforms, avoiding the situation they’d faced in the 1980s when Nintendo held the reigns. In any case, it must have been a relief to Microsoft to finally have these titles available, since legions of fans would pass on any system that didn’t offer the latest and greatest sports titles. Indeed, EA’s failure to support Sega’s Dreamcast clearly contributed to it its early demise.

Sega also played an important role in establishing the Xbox in the early years. With their console manufacturing days behind them, the company turned to software development, and released several key games for the Xbox in 2002. These included a string of sports titles as well as Jet Set Radio Future, Panzer Dragoon Orta, Crazy Taxi 3: High Roller, and Sega GT 2002. These Xbox-exclusive titles may well have convinced many former Dreamcast fans to choose the Xbox over the PlayStation 2 for their next console.

The Official Xbox Magazine had two preview issues prior to its first official issue. Shown here is the second preview issue for November 2001. From issue 1 to issue 52, the magazine came with a demo disc playable on the Xbox. Starting with issue 53, all demo discs were targeted exclusively to the Xbox 360. Like all of the official console magazines, the Official Xbox Magazine provided a key resource in helping to grow the Xbox’s community.

Outlaw Golf.

Outlaw Golf (2002, Hypnotix)

While the sport of golf has seen plenty of videogame adaptations over the years, none have been quite like this zany, Happy Gilmore-like take on the genre. Forget about old white men in plaid plants and polo shirts. These golfers include strippers, failed rappers, and former inmates. Steve Carell of The Office fame is the game’s hilarious announcer. While the theme, dialog, and crazy antics are certainly part of the game’s appeal, the team did a great job with the gameplay, allowing up to four players and featuring a fully adjustable camera. Be sure to check out its sequels, Outlaw Golf: 9 Holes of X-Mas and Outlaw Golf 2, as well as Outlaw Volleyball and Outlaw Tennis.

The last Xbox rolled off the assembly line at the end of 2008, purportedly to clear the deck for the 360. However, Nvidia had stopped making graphic chips for them back in 2005, following a vicious falling out over pricing. For the 360, Microsoft turned to Nvidia’s fiercest rival, ATI, who supplied them with a new chip called the Xenos, a Greek word whose meaning roughly translates to “uncertain relationship.” By contrast, Sony didn’t halt production of the PlayStation 2 until January of 2013. Fortunately for fans of the older games, the 360 is backward-compatible with many games for the original system, assuming your 360 is equipped with an official hard drive.

The fact remains that the Xbox is an intriguing chapter in the history of the videogame industry. In the late 1990s, the industry was completely dominated by Japan, and only a company with vision, highly skilled workers, and—most importantly—bottomless cash reserves, had a chance to alter the status quo. Microsoft was able to muscle its way in by sheer force, restoring to the West at least some of the control ceded to Japan after the Great Videogame Crash. They also made it much easier for Windows game developers to transition to the more lucrative console market, becoming a prominent source for key genres like first person shooters that were previously dominant on computers.

Technical Specifications

The original Xbox had a 32-bit CPU based on Intel’s Pentium III Coppermine chip. This chip was capable of speeds up to 733 MHz. It had 64MB of main memory. Most games run at 640 × 480 resolution, which was fine for standard televisions. However, after HD displays became more common, some games began supporting 720p or even 1080i resolutions with the VGA and Xbox High Definition AV Pack cable options.13 Its Nvidia-built GPU was a powerful beast in its day, with twice the memory bandwidth of the PS2 and better anti-aliasing.14 Sound output was stereo, with up to 256 channels. The aforementioned AV Pack enabled Dolby Surround Sound, provided you had the sound system to take advantage of it. Famously, the Xbox was the first game console to feature an internal hard drive: an 8-gigabyte drive spinning at 5400 RPM. 8 MB memory cards were used to transfer data from system to system. The Ethernet support was integrated. Unlike the later 360, the four controller ports of the original Xbox were proprietary and would not function with standard USB-compatible devices without modding.

Psychonauts.

Psychonauts (2005, Majesco)

Tim Schafer’s Psychonauts remains one of the developer’s best-known and best-loved titles. Self-described as a “psychic odyssey though the minds of misfits, monsters, and madmen,” Psychonauts is certainly one of the most bizarre, yet endearing games you’ll find on the system. This 3D-platformer features great level design, unforgettable characters, and plenty of fun sequences and puzzles. If you like the originality found in Psychonauts, be sure to check out Blinx: The Time Sweeper (2002, Microsoft).

The Xbox was often criticized for its bulk and weight, but it was actually quite comparable to the original PS2. It weighed in at 8.5 pounds, which was really only a little over a pound heavier than the original PS2. The Xbox’s dimensions were 12.5 × 4 × 10.5 inches; the PS2’s were 12 × 7 × 3 inches. The later PS2 “Slim” was 4.3 pounds and 10 × 5 × 1 inches in size.

The Accessories

The standard Xbox Controller was nicknamed “The Duke” or, less kindly, “Fatty.” Although Microsoft insisted that it was “lighter than it looks,” it weighed just under a pound. Its dimensions were 6.5 × 5 × 3 inches. It was also widely regarded as one of the worst controllers ever released. IGN ranks it as the second worst controller ever. Chris Harris, who compiled the list for IGN, wrote,

I may be able to palm a bowling ball, but even I couldn’t comfortably or effectively wrap my mitts around Microsoft’s original monstrosity. The gargantuan thing was clearly made for the Rock Biter from The Neverending Story. What a shame the Nothing took him away.15

The controller was award-winning, however. Unfortunately, the award in question was a Guinness World Record for biggest controller ever.

While few were especially pleased with the controller, at least it was built with 3D-gaming firmly in mind. It offered two analog sticks, a D-pad, six pressure-sensitive buttons, and start/back buttons. The two trigger buttons on the sides were great for both left- and right-handed gamers. It also had two slots for accessories, which included a memory card or headset. It also had “rumble,” which meant it could vibrate to provide more visceral feedback.

In 2002, Microsoft replaced the Duke with the Controller S, nicknamed “Akebono.” Originally only released in Japan, this controller was 8.3 × 6.3 × 1.7 inches, and weighed in at 8 ounces—about half the weight of the original. Although nearly the same length and width as its predecessor, it was also thinner, a profile most gamers found more accommodating. There were, of course, plenty of third-party controllers. Logitech offered the best wireless controller, although some still complained of issues with latency (especially in competitive Xbox Live matches).

On the left is the original Xbox game controller, “The Duke.” On the right is the Controller S or “Akebono” replacement. Below the two controllers is the remote control contained in the optional DVD Wireless Remote Control Kit.

Perhaps the most interesting Xbox controller is the one required to play Capcom’s Steel Battalion (2002). This mech-style affair had two joysticks, dial, thumb pad, switches, forty buttons, and three foot pedals. Bundled with the game, it cost $200, and was easily the most ambitious third-party product released for the Xbox. It’s since become a collector’s item, even though only one other game supported it, the online multi-player-only sequel, Steel Battalion: Line of Contact (2004).

Another popular accessory for the Xbox was the $30 DVD Wireless Remote Control Kit, which was basically a controller port dongle and remote control that enabled users to play movie discs on their Xbox. While obviously useful, many users complained about having to spend the extra money just to play DVDs. After all, the PlayStation 2 didn’t need an add-on for this purpose. Apparently, Microsoft didn’t want to increase the cost of the Xbox by including built-in support for DVD playback, which would have required paying substantial fees to the DVD Format/Logo Licensing Corporation, a Japanese company. Instead, only people who bought the remote would shoulder this cost.

Steel Battalion cost $200, but it boasted one of the most impressive-looking controller setups ever available for this or any other platform. Shown is the second release of the controller with the blue, rather than green, buttons.

Finally, for gamers who wanted to compete without having to go online, there was the Xbox System Link Cable. Playing with this setup required two Xboxes as well as two copies of the game in question—provided it had support for this option. Multiple Xboxes could also connect over a LAN (local area network). In this way, up to 16 players could play games like Halo: Combat Evolved in four-way split-screen mode, using four Xboxes. This setup was quite common in college dormitories, especially where policies prohibited online gaming.

Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic.

Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (2003, BioWare Corporation)

BioWare rose to prominence with its Baldur’s Gate series for Windows in the 1990s, which revitalized the Dungeons & Dragons license for videogames. This 2003 game, however, trades long swords for light sabers and blasters. It was custom-built for the Xbox, with gameplay eminently suited for playing with a controller. The game’s polished graphics, story, characters, and “real-time with pause” combat were a big hit with Xbox fans, and many still consider it the greatest Star Wars game ever made. The best part is, you can role-play the character as a noble Jedi—or an evil Sith. If you love the polish found in this hybrid RPG, be sure to check out the equally excellent Jade Empire.

The Microsoft Xbox Community Then and Now

While there are obviously many different kinds of people who enjoyed many different kinds of play on the Xbox, the most visible were the competitive Xbox Live crowd. Games such as Halo: Combat Evolved, Call of Duty, Counter-Strike, and Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six 3—to name a few—provided endless hours of multiplayer action. When these players weren’t gaming, they might be visiting one of the many online forums dedicated to the platform and its games, comparing strategies, notes, or setting up their own tournaments and challenges.

As with any popular console, videogame magazines, both multiplatform and dedicated to the platform, were a great source of information for the Xbox. Perhaps the greatest of these magazines was the Official Xbox Magazine, which started producing monthly issues just before the console’s official launch. Each issue came with a demo disc playable on the Xbox, which lasted for 53 issues until coverage shifted primarily to the Xbox 360.

After the introduction of the 360 in November 2005, official support for the original Xbox dried up quickly. That said, there’s still plenty of enthusiasm for modding and hacking the original Xbox. You can even buy a book by Andrew “Bunny” Huang called Hacking the Xbox: An Introduction to Reverse Engineering, which promises to teach you “how to enjoy a Microsoft Xbox game console without the mindless tedium of playing video games.” It’s certainly a must-read for anyone interested in this often subversive community of electronics hobbyists.

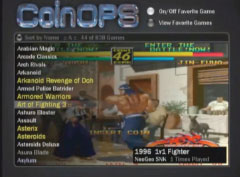

Homebrew for the original Xbox is plentiful, with over 500 games listed at The ISO Zone (www.theisozone.com). Many of these are ports of games from other systems, such as Beats of Rage, but there are also plenty of originals available. Many of these projects are compiled with unauthorized copies of the Microsoft System Development Kit for Xbox, which means they’re technically illegal.

The CoinOPS MAME arcade emulator for modded Xbox consoles.

Collecting Microsoft Xbox Systems

Acquiring an original Xbox in good condition is cheap and easy from a variety of sources, including the usual auction sites. Of course, you’ll need to fire it up to make sure it still works. It’s relatively easy to replace broken hard drives, disc drives, and power boards, and if you’re really feeling ambitious, even motherboards. Still, unless you get a broken Xbox for free or just enjoy tinkering, you’re probably better off just buying another Xbox in working condition. In fact, if you’d like to use an Xbox as a multimedia center or emulation machine, even modded Xbox consoles are not that difficult to find or particularly expensive.

The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay (2004, Vivendi Games)

Most games based on movie licenses are quickly made cash-ins that rely almost entirely on the appeal of the movie to sell copies. This game is a rare example of the reverse: a game that is better than the film it’s based on. Voiced by Vin Diesel (who had a hand in development), this game allows you to switch between first-person and third-person mode, which allows for both stealth and intense combat sequences. Critics raved about the happy marriage of story and gameplay. When the only recurring complaint about a game is that it left gamers wanting more, you know the designers did a great job. No matter what you think of Vin Diesel, you’ll find much to enjoy about this game.

Microsoft released several “special edition” Xbox consoles themed on certain games. The Halo Special Edition Green Console is translucent green and included a matching green controller. Then there’s the lime green Mountain Dew-branded edition, which the soda-maker gave away in a sweepstakes. There are also many editions that weren’t released in the United States, such as the Panzer Dragoon Orta edition only available in Japan. Surprisingly, even these rare special editions seldom sell for more than a few hundred dollars. There are also two editions, one for the launch team and another for partners, which feature a silk screened message from Bill Gates on the jewel (the circular logo on the top of the Xbox). The chances of encountering one of these in the wild are quite slim, since only 60 of each exist. If you do manage to find one, though, you’re in luck—they can bring in $1500 or more at auction.

As the box copy proudly proclaimed, the Halo Special Edition Green Console included an “Exclusive Green Halo Console, Special Edition Green Controller, and a full version of Halo!”

Games for the original Xbox are also quite cheap and plentiful, with few rarities. Perhaps the most collectible games are Steel Battalion, mentioned above, and Marvel vs. Capcom 2, an extremely popular title that is nevertheless becoming hard to find. Expect to pay triple digits for an unopened copy. Another unexpectedly collectible game is Barbie Horse Adventure: Wild Horse Rescue, which has a reputation for being so unbelievably bad, you have to see it to believe it.

Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory (2005, Ubisoft)

Although the late Tom Clancy is best known for writing action-packed military-themed novels, among gamers his name conjures up this series of stealth games. The series launched in 2002 with Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell, which introduced Sam Fisher, an agent of the NSA’s “Black Operation.” Instead of blasting through levels with a grenade launcher, Fisher must rely more on brains than brawn, using all manner of cool gadgets—like a snaking camera to look under doors. The multiplayer mode was a huge hit on Xbox Live. Chaos Theory was the third Fisher game, and is less linear than the preceding titles, with more viable solutions for the problems Fisher encounters. While everyone raved about the graphics, it was really the highly flexible gameplay and ambience that sealed the deal. For another excellent Tom Clancy game series and game, be sure to check out Rainbow Six 3.

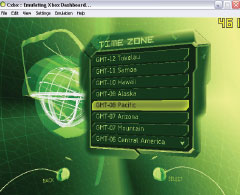

Emulating the Microsoft Xbox

At this point, it’s much, much easier to buy either an original Xbox or hard drive-equipped Xbox 360 to play Xbox games. Although many people assume the Xbox is just a PC in disguise, it’s actually only similar. The proprietary Nvidia hardware, in particular, is a problem, since the company has not released the technical specifications—information vital for anyone attempting to build an emulator. The audio system, BIOS, and video encoding systems are problematic as well. Furthermore, even if emulator developers had full access to the schematics, source code, and other secret documentation, you’d likely need an extremely powerful PC to run the games at a decent frame rate.

That said, there are two options currently available: Xeon and Cxbx. Xeon only runs Halo: Combat Evolved, but is still quite rough. Cxbx has a larger list of games that work with it, but its authors acknowledges that Direct3D, sound, and networking support are still lacking. Turok Evolution is the only fully playable retail game.

In short, emulating the Xbox is not a viable option, and probably won’t become so until at least another generation or two. For now, get a used Xbox for full compatibility, or a backward-compatible Xbox 360 instead.16

The Cxbx emulator running the Xbox dashboard.

1 See Chapter 3.4.

2 See Brian Ashcraft, “Square Enix Says Japanese Retail ‘Prejudiced’ Against Western Games,” Kotaku, March 1, 2010. Yoichi Wada, a business executive at Square Enix, said that “even now, there have been people in Japan using the label youge (Western games) with a terribly discriminatory meaning.” For these gamers, a youge product doesn’t even count as a game, but rather something cheap, fake, or alien. Wada argued that it was retailers who were most guilty of this prejudice, refusing to stock non-Japanese titles on their shelves.

3 See Chapter 1.8 on the Coleco Adam or Chapter 1.5 on Mattel’s attempts. With that in mind, Microsoft did do a fusion of sorts in 2013 when it was announced that the Xbox One would run an operating system functionally similar to Windows 8, whose core technology now powers all of their platforms.

4 See “The Xbox Story,” VG24/7, August 5, 2011, www.vg247.com/2011/08/02/the-xbox-story-part-1-the-birth-of-a-console.

5 A “kernel” is a middle manager that shuffles between software applications and hardware. This frees up developers from having to worry about interacting directly with the CPU or other components, which requires a great deal of highly specialized knowledge. The Xbox team had a massive advantage over their Windows counterparts, since they knew the exact make and model of the components installed in every Xbox.

6 See Jeffrey M. O’Brien, “The Making of the Xbox,” Wired, November 2001, www.wired.com/wired/archive/9.11/flex.html.

7 The Xbox sold 1.53 million units in its first three months in North America alone, a record that wouldn’t be broken until the blockbuster launches of both the PS4 and Xbox One in November 2013.

8 www.microsoft.com/en-us/news/press/2002/apr02/04–08halomillionpr.aspx.

9 See Mike Futter, “The Complete History of Xbox Live (Abridged),” Game Informer, May 19, 2013, www.gameinformer.com/b/features/archive/2013/05/19/the-complete-history-of-xbox-live-abridged.aspx.

10 Fortunately for Microsoft, the playing field would even out dramatically in the next generation—the PS3 and 360 each sold around the same number of units worldwide.

11 See Dean Takahashi, “The Making of the Xbox: Microsoft’s Journey to the Next Generation (Part 2),” Venturebeat, November 15, 2011, http://venturebeat.com/2011/11/15/the-making-of-the-xbox-part-2. Read more at http://venturebeat.com/2011/11/15/the-making-of-the-xbox-part-2/#Swm5uWsdgVOqw6k1.99.

12 This figure is according to CNN’s analysts. See Chris Morris, “Microsoft Launches Xbox,” CNN Money, November 15, 2001, http://money.cnn.com/2001/11/15/technology/xbox.

13 A list of 157 Xbox games with HD support can be found at Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Xbox_games_with_HD_support. Dragon’s Lair 3D: Return to the Lair (2002, Ubisoft) was the first console game capable of 1080i resolution.

14 Aliasing is a fairly technical concept, but it amounts to using color blending techniques to smooth out the jagged-looking lines of pixel-based computer graphics. To picture this, draw a diagonal on graph paper by coloring in the squares with dark black pencil. Now imagine filling in the squares around this line with a lighter gray. If you step back from the paper, the line will look smoother than before. If you’d like to learn more, see Jason Cross’s detailed explanation at Extremetech, www.extremetech.com/computing/78546-antialiasing-and-anisotropic-filtering-explained.

15 See Craig Harris, “Top 10 Tuesday: Worst Game Controllers,” IGN, February 21, 2006, www.ign.com/articles/2006/02/22/top-10-tuesday-worst-game-controllers.

16 For the full list of Xbox games compatible with the Xbox 360, see http://support.xbox.com/en-US/games/xbox-games/play-original-games.