History

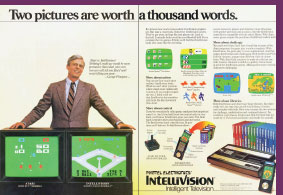

When reflecting back on the storied career of George Plimpton, the celebrated editor, journalist, writer, actor, and gamesman, there are few among us who would think first and foremost of his stint as official pitchman for the Mattel Intellivision. Still, while his tenure as the face of Mattel’s console will likely be relegated to the footnotes section of his official biographies, for Mattel, the hiring of Plimpton proved an insightful and apropos choice. Along with Bill Cosby for Texas Instruments and Alan Alda for Atari, Plimpton was one of the most prominent and memorable personalities used as weapons in the “spokesperson wars” of the 1980s. While not as well-known among the general public as Cosby or Alda, Plimpton was nevertheless well-suited to the role. Primarily a well-regarded journalist, the versatile Plimpton was perhaps most famous for competing in various pro sporting events and then writing about the details of his often humbling experiences from his uniquely novice perspective.1 Even if you didn’t get the clever connection when he endorsed Mattel’s superior sports games in television commercials, Plimpton’s droll and pitch-perfect delivery of the technical merits of the Intellivision over its biggest rival, the Atari 2600 VCS, helped Mattel’s marketing department position their product as the intelligent choice for the sophisticated, informed consumer.

The story of the Intellivision’s unusually long 12-year run begins even further back, with the founding of Mattel in 1945. Mattel was then primarily a manufacturer of picture frames and dollhouse accessories. After the wildly successful introduction of the Barbie doll line in 1959, however, the company made the obvious decision to focus entirely on toys.

Much to the delight of Mattel and little girls everywhere, the Barbie franchise had great legs, and the greatly expanded profits allowed the company to diversify with a talking doll (Chatty Cathy) in 1960 and the See ’n Say educational toys in 1965.2 The Hot Wheels line, unveiled in 1968, drove the company to the top of the American toy industry.

An early two-page Plimpton ad from the March 1982 issue of Electronic Games touting the Intellivision’s comparative sophistication.

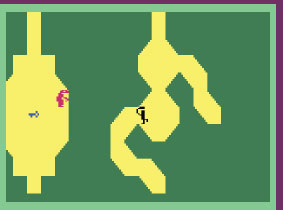

Cloudy Mountain running on the Bliss emulator.

ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Cartridge (1982, Mattel)

Also known as ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Cloudy Mountain Cartridge3 to distinguish it from the later games, Mattel was the first videogame company to get the coveted TSR license.4 While Cloudy Mountain didn’t necessarily capture the more cerebral elements of TSR’s pen-and-paper role-playing classic, it was still a smashing action-adventure. The goal is simple: guide your archer through randomly generated, scrolling mazes in search of treasures and weapons in your quest to recover the two pieces of the Crown of Kings. The game was later referred to as Adventure or Crown of Kings after the license expired, so you may need to track it down under one of those names.

Today, Mattel is one of the world’s largest toy-makers, but a series of disasters in the 1970s made this destiny anything but certain. After losing one of their largest toy plants in a fire, a 1971 dock workers’ strike ruined their crucial Christmas season. Another misstep included a toy World War II-era German airplane complete with swastika decals, which unsurprisingly offended the American Jewish Congress. On top of all these woes, the SEC was investigating them for lying on their financial reports, further tarnishing their image. Mattel needed something drastic to recover its reputation as well as its finances, and by the late 1970s made the fateful decision to gamble on the videogame market.

In 1977, Mattel, under its Mattel Electronics line, produced the seminal Auto Race, the first all-electronic handheld game. Crude by today’s standards, with visuals represented by red LED lights and sound consisting of simple beeps, Auto Race nevertheless showed the entertainment potential of a portable electronic game. The novel product was a huge success, spawning several other handheld games such as Football and Battlestar Galactica, the latter being the first of many examples of Mattel Electronics’ deep-pocketed licensing prowess.5 These games sold millions and gave Mattel the confidence to move into the fledgling videogame console market in 1978. Development on the Intellivision Master Component began.

Mattel successfully test marketed the Intellivision in Fresno, California, in 1979, along with four games: Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack, The Electric Company: Math Fun, Armor Battle, and Backgammon. The following year, Mattel went national, and quickly sold out the first year’s production run of the popular systems. The new electronic games sent the company’s reputation flying high again, and accounted for a full quarter of their sales by the end of the year.

The Master Component was a large, flat rectangular box with stylish brown-and-gold detailing. Unlike the Atari 2600, this system’s two controllers were attached to the system and could not be removed. They had unique thumb-operated control discs with 16 possible movement directions, which was twice the number of a typical digital joystick.

The controllers also had 12-button keypads with two action buttons on each side. The top two action buttons were wired together, so only three unique functions could be performed by the four action buttons. Since the control disc and action buttons registered as the same inputs, they could not be used simultaneously with the keypad buttons. On the plus side, simultaneously pressing the 1 and 9 keys would pause any game, an unusual feature for the time.

A page from an early 1981 Mattel Electronics dealer catalog enumerating the many benefits of the Intellivision Master Component. Dealer pricing was $210 each for a package of six consoles.

Treasure of Tarmin running on the Bliss emulator.

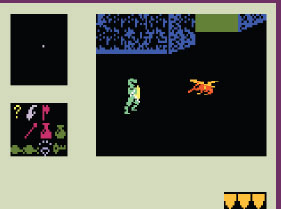

ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Treasure of Tarmin Cartridge (1983, Mattel)

Unlike Cloudy Mountain’s modified top-down perspective, Treasure of Tarmin went for a more traditional first-person dungeon view and placed less emphasis on action and more on strategy. The objective is still simple: slay the minotaur who guards the treasure, but the turn-based battles, stats, and enemy types are more faithful to the type of role-playing elements found in the source material and make for a unique play experience from the time period. Post-license, the game has been referred to as Minotaur.

Because of its design quirks, Intellivision controllers were notoriously difficult to use. Although the multifunction controllers worked well for games requiring complex input, such as the genre-defining Major League Baseball (1980) and other sports games, they proved sluggish for titles that required precise directional movement or timely button presses, such as the Nintendo arcade port Popeye (Parker Brothers, 1983). Regardless of their usability, it’s not hyperbole to say that they stand today as the single most divisive and controversial—as well as hardest to reproduce or emulate—of the stock console controllers.

The heart of the Intellivision was a 16-bit microprocessor from General Instruments, quite a step up from most other videogame and computer systems at the time, which still relied on the cheaper 8-bit microprocessors. The Intellivision’s sound chip, the General Instrument AY-3-8910, was also notable, outputting three 8-bit sound channels and a noise generator. By contrast, the Atari 2600 had only two one-bit channels. The AY-3-8910 was also a popular choice for arcade machines, allowing Intellivision arcade ports to sound more authentic.

Screenshot from the Bliss emulator showing NFL Football (1980), one of many great Intellivision sports games that benefited from its unique controller.

The machine boasted a 16-color palette, but games with more than eight sprites (called “moving objects”) would cause the screen to flicker—something the company’s marketing team would not allow. Fortunately, Mattel’s programming team devised a clever method called “GRAM sequencing” to work around this issue. The technique can be seen in games such as Space Armada (1981) and Star Strike (1982).

Astrosmash running on the Bliss emulator.

Astrosmash (1981, Mattel)

For a platform that emphasized its sophistication, John Sohl’s Astrosmash was anything but. The game’s premise was simple: shoot or avoid the falling asteroids, spinners (bombs), homing missiles, and patrolling flying saucers. Part Space Invaders, part Asteroids, Astrosmash was exactly the type of non-stop action that videogame players of the day craved, proving, when programmed correctly, how versatile the Intellivision’s hardware really was in delivering the goods. Perhaps Astrosmash’s most innovative and welcome feature is that as the game gets faster and harder at higher levels, as you start to lose lives, the pace and difficulty starts to scale back down again. This makes long play sessions and big scores a real possibility for players of even modest abilities.6 Along with Don Daglow and Ji-Wen Tsao’s widely imitated big fish-eat-smaller fish game Shark! Shark!, Astrosmash helped define action gaming on the Intellevision.

At first, Mattel farmed out game programming duties to a company named APh Technological Consulting. In 1980, however, they decided to form their own in-house team, which became known as the Blue Sky Rangers. These nine programming gurus became intimately familiar with and passionate about the hardware, innovating impressive software tricks, such as the GRAM sequencing technique mentioned above. Several of the team’s members would continue to produce software that pushed the platform’s hardware long after Mattel officially dropped support. They took their name from their division’s formal brainstorming meetings, which were called “blue-skying” sessions. Howard Polskin, a writer for TV Guide who interviewed the group in 1982, describes them as eccentric math wizards whose eyes were “sunken and hollow from countless hours spent toiling indoors in front of computer terminals.” Like other software companies at the time, their management preferred to keep their identities secret to prevent their being lured away by the competition. Still, the team managed to have a lot of fun playing each other’s games, hanging out at the local arcade, and throwing Frisbees at the park.

Although an unthinkable practice today, Mattel followed Atari’s example with its VCS, and sublicensed the rights to distribute the Intellivision Master Component under different brand names, including the Sears Tele-Games Super Video Arcade, Radio Shack Tandyvision One, and GTE Intellivision. Except for cosmetic differences, most of these systems were identical to the original Master Component. However, the Sears version offered detachable controllers, which were a welcome improvement over the original model, as well as a different default title screen. In addition, as it did with the Atari VCS, for a time, Sears rebranded Mattel games under its own label.

A page from the 1982 Sears holiday catalog showing the rebranded Tele-Games Super Video Arcade console.

The Keyboard Component

Despite the success and sophistication of the Intellivision, Mattel didn’t always deliver on its promises. The most infamous of these is the Keyboard Component, an add-on that would turn the console into a full home computer system. The idea had been around for a while, and other consoles already had their own computing add-ons, including the Bally Home Library Computer (aka Bally Astrocade), APF M-1000, Magnavox Odyssey2, and Atari 2600. However, these were either poorly marketed and distributed or simply not useful enough to resonate with consumers. Mattel was in a position to change all of that.

Mattel told consumers they would have the Intellivision Keyboard Component by 1981. Despite that promise, ambitious technical specifications, production delays, and manufacturing issues made the Keyboard Component’s timely release impractical. Internally known as the “Blue Whale,” the component was being developed by Dave Chandler and his team of engineers, the same group who had finalized the Intellivision’s design. Unfortunately for Chandler and Mattel, the team simply could not find a way to make the component cheap enough for release.

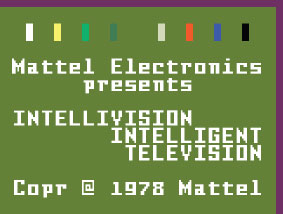

Mattel was promising “Intelligent Television” from as far back as its original creation in 1978, as this title screen screenshot from a dealer demo cartridge via the Bliss emulator demonstrates.

Comedian Jay Leno perhaps summed it up best at the 1981 Mattel Electronics Christmas party, “You know what the three big lies are, don’t you? ‘The check is in the mail,’ ‘I’ll still respect you in the morning,’ and ‘The Keyboard will be out in the spring.’” To Mattel’s detriment, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was not as amused by the delay, and the US agency for consumer protection became involved after receiving a series of complaints. Once again, Mattel was under federal scrutiny, casting a cloud of doubt over investors.

Beauty and the Beast running on the Bliss emulator.

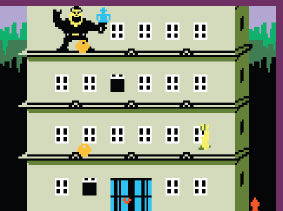

Beauty and the Beast (1982, Imagic)

Coleco’s Donkey Kong (1982) arcade conversion for the Intellivision was the definition of mediocre, with grating sound, odd looking graphics, and sluggish play. Adding insult to injury was the fact that it was one of the three Coleco Intellivision releases that, thanks to Mattel’s hardware tweaks, didn’t work on the Intellivision II. While Intellivision fans would finally receive a brilliant new homebrew conversion of the arcade game as DK Arcade in 2012, courtesy of Carl Mueller, Jr., the wait wasn’t quite as bad as it could have been thanks to Wendell Brown’s Beauty and the Beast. The premise was to rescue the girl from the boulder-hurling bully at the top of the high rise building. What the game lacked in originality by cribbing from Nintendo’s Donkey Kong, it made up for in masterful execution. With fully animated graphics, lots of sound effects, intermissions, multiple levels, and many other little flourishes that kept the gameplay fresh, even without a compelling license, this was the type of platforming action that Intellivision gamers craved. Although not a direct sequel, Steve DeFrisco’s island-based platformer Tropical Trouble (1983) uses a similar premise and graphics, just with more innovative side-scrolling gameplay.

Although Mattel was eventually able to release a few units to test market and to those consumers who complained the loudest, the Keyboard Component proved too costly for Mattel to reliably mass produce on a large scale at a competitive price. It certainly wasn’t for lack of effort, though.

The Keyboard Component added an 8-bit 6502 microprocessor, expandable RAM, full keyboard, digitally controlled cassette drive for both data and audio content, expansion ports, and a printer port. All of its features, in addition to the Master Component’s own capabilities, made it more than a match for nearly any other stand-alone computer of the day. However, each setback and delay reduced this advantage until, finally, it was a case of too little, too late.

The roughly 4000 Keyboard Components that were eventually produced were not enough to appease the FTC. The agency imposed daily fines, which prompted Mattel to move to an alternate plan with a much lower priced, but far less capable, computer expansion, the Enhanced Computer System (ECS). Even this unit was not released until 1983.

The Keyboard Component was extensively advertised for a number of years in Mattel catalogs, including this example from 1982, which alludes to its availability in “test markets.”

Despite its problems with the Keyboard Component, the Intellivision and its software continued to sell, capturing nearly 25 percent of the home videogame market at its peak. With its growing success, Mattel Electronics was spun off as a separate company under the Mattel banner in 1982. In that same year, the company introduced the Intellivoice Speech Synthesis Module, which, after the Magnavox Odyssey2’s The Voice, was the second such device of its kind for a videogame console—and this time, kids would not need to pull a string to hear it.

Through clever use of the built-in prerecorded sound samples and custom recordings loaded on demand for each game, every Intellivoice title had its own unique identity. Although impressive even at the necessarily low sample rates, only five speech games were released. Poor sales of the Intellivoice spurred Mattel to provide a voucher for the module free by mail with the purchase of a Master Component.

That wasn’t all Mattel was doing to make 1982 the year of the Intellivision, however. They also released a new version of the console, the sleeker and much smaller Intellivision II Master Component, a white and black unit with removable controllers and external power supply. So why a new Intellivision? Michael Blanchet quipped in the April 1983 issue of Electronic Fun with Computers and Games,

For one thing, it’s spiffier than the original. For another, what better way to entice owners of other systems—and those who don’t own any system at all—to switch to Mattel than by offering something new? Here’s your chance to be first on the block all over again!

The real reason wasn’t simply refreshing the line for marketing purposes, however. It was also a bid to reduce production costs and add some highly desirable features. A special video input was added to the cartridge port to make the System Changer possible, which allowed the Intellivision II to play Atari 2600 games. This refresh also gave Mattel Electronics an excuse to introduce another “feature,” a secret validation check in the hardware that made third-party software inoperable. This check affected Coleco’s 1982 arcade conversions—Donkey Kong, Mouse Trap, and Carnival—and inadvertently rendered Mattel’s own Electric Company Word Fun (1980) unplayable. Fortunately, for the health of the console’s game library, internal and external development groups soon figured out how to bypass the check.

B-17 Bomber running on the Bliss emulator.

B-17 Bomber (1982, Mattel)

While it’s arguable if B-17 Bomber is a particularly great game, or even the best of the games that require the Intellivoice module, there’s no denying the appeal of its total package. It’s an intense, but approachable first-person perspective flight simulation with some pretty memorable speech effects. As you fly your bomber on its missions to attack strategic map targets throughout Europe, your crewmate warns you of everything from impending attacks (“Fighter, six o’clock”) to when an objective is in range (“Target in sight!”)—complete with charming southern accent. This ability to add some personality to its speech effects gave the Intellivoice a leg up on most other speech solutions of the era, and one that in this case added tremendously to the personality and appeal of the core game. It was indeed a rare feat for the time. If you’d like to experience an equally intense, but rather more unusual speech game, check out Mattel’s Bomb Squad (1982), which tasks you with diffusing bombs with four different tools in the right order, all within tight time constraints.

The following year, Mattel released the ECS, which retailed for under $150. The ECS, like the System Changer, matched the styling of the Intellivision II, though it was compatible with all Intellivision models and the Intellivoice. The computer add-on featured a detachable chiclet keyboard, an expansion box, and power supply. It also added an extra 2KB of memory, three extra channels of sound, two additional controller ports, and the ability to accept a standard tape recorder and a printer, the latter being the same as the one for the original Keyboard Component and Mattel Aquarius computer. A simplified version of BASIC was built in along with the ability to play musical tones.

Despite this flurry of activity, however, the future of the Intellivision’s add-ons was anything but certain. Mattel Electronics had a management shake-up in mid-1983 and shifted its focus to software for its own as well as competing videogame and computer systems. This shake-up took priority away from initiatives such as the ECS and Intellivoice; only the Intellivision consoles would continue to receive advertising and software support. In the end, the ECS was only supported with a music keyboard add-on and five cartridges.

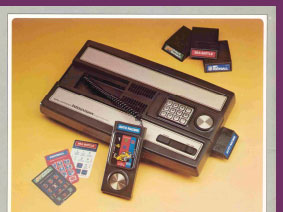

An Intellivision II with Intellivoice, ECS, and music keyboard. Also pictured are the printer and standard cassette recorder from the Mattel Aquarius, both of which were compatible with the ECS.

The End of the Line

Following industry-wide losses from the Great Videogame Crash and too many costly dalliances in hardware development, Mattel Electronics was closed in January 1984, and its assets sold to a liquidation company owned by Terry Valeski, who was previously Mattel Electronics’ senior vice-president of marketing and sales.

In addition to handling old inventory, Intellivision, Inc., sold some complete, but previously unreleased cartridges. Once most of the old Mattel Electronics inventory was sold, Valeski bought out Intellivision Inc.’s remaining assets from the other investors and formed INTV Corporation.

INTV Corporation hired former Mattel Electronics programmers to produce new Intellivision games. The company also released the INTV Master Component (called INTV System III and INTV Super Pro System, among other names), which was based on the easier to reproduce Intellivision Master Component with only minor cosmetic changes.

Like Atari’s 2600 Jr., INTV’s system was marketed as a low-cost alternative to the newer and more powerful systems of the day. The main console sold for less than $60 and many of the games were less than $20. INTV continued to produce new products up to 1990, when the company filed for bankruptcy protection, closing its doors for good in 1991.7

Today, several of the original Blue Sky Rangers run Intellivision Productions, Inc., which now owns the Intellivision branding and rights to most of the technology and games. This group regularly releases TV Games and compilation software packs for modern videogame consoles, computer systems, and portable devices based on the Intellivision line of products.

Diner running on the Bliss emulator.

Diner (1987, INTV Corporation)

Ray Kaestner’s Diner was an unlikely sequel to his earlier Data East coin-op conversion of BurgerTime, among the Intellivision’s best titles. Much like Data East’s own attempt at a second game, BurgerTime’s sequel was originally going to be PizzaTime, with development starting but never finishing at Mattel’s French offices. Instead, what originally started out life as a Masters of the Universe II prototype in Mattel’s California office, was finished by Kaestner years later for INTV Corporation as Diner. Kaestner’s creation, while officially licensed, was still considered an unofficial sequel, subordinated by the growing number of Data East’s own arcade follow-ups. For a game with such a tortured history, you’d be forgiven for thinking Diner would turn out to be something of a dog’s dinner. Luckily, for Intellivision fans, this isometric platform game was anything but. Kaestner crafted a wholly original game for chef Peter Pepper to star in, with old favorite bad guys, the hot dogs, joining new villains, bananas, cherries, and their leader, Mugsy the Mug o’ Root Beer, for fun on the run. Diner is among the best original titles unique to the Intellivision and still holds a great deal of appeal today.

There were 125 cartridge games released for the Intellivision between 1979 and 1990. Several additional homebrew cartridges, including both original creations and previously unreleased prototypes, have been released since 2000.

In general, these games featured some of the best graphics and sound for any early videogame system, at least before Coleco released its more powerful ColecoVision. Still, gameplay speed often seemed a bit slower on an Intellivision than on rival machines.

Mattel generally grouped the games of its first software releases into categories called “networks,” including Sports Network, Action Network, Gaming Network, Space Action Network, Strategy Network, Children’s Learning Network, and Arcade Network, each with its own distinctive box color. However, Mattel’s marketing discontinued the concept in late 1982 since most games were falling into the Action Network category (mostly at their request).

For the Intellivision Master Component’s first two years, the system came packaged with Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack (1979), which played great one- or two-player versions of the title games, complete with an animated dealer. This was followed by a newer pack-in, Astrosmash (1981), one of the system’s more popular action titles. Shortly after the release of the Intellivision II, a coupon for the excellent conversion of Data East’s popular arcade game, BurgerTime (1983), was included as well.

The Intellivision is most famous for its extensive range of quality sports games, including Mattel’s own Major League Baseball, NFL Football, NBA Basketball, NHL Hockey, and PGA Golf, all released in 1980 and among the first games licensed from professional sports associations. Most of these titles were the best sports games of their time on any platform. They made great use of helpful overlays on the keypad for more sophisticated in-game options. The overlay for Major League Baseball, for instance, shows a baseball field with the various fielders in position. Players would press the player they wanted to go after the ball and who should receive it when it was caught. It was a great system in an era before modern touchscreens. INTV would later commission renamed updates for many of these games that introduced enhanced features and support for single players, although without the expensive licenses.

Microsurgeon running on the Bliss emulator.

Microsurgeon (1982, Imagic)

At a time when most games featured blocky, barely recognizable visuals, Rick Levine’s Microsurgeon upped the ante with its bold, colorful maze-like presentation of an internal view of a critically ill patient’s head and body. Reminiscent of the 1966 sci-fi movie classic Fantastic Voyage, the player navigates a miniature robot probe through the patient’s blood stream, removing everything from brain tumors to blood clots near the heart, all while avoiding attacks from white blood cells. Dave Durran’s sparse, but effective sound design, helps ratchet up the tension. For more Microsurgeon, be sure to check out the later ports for the Texas Instruments TI-99/4A and IBM PCjr, each of which features a slightly different take on the Intellivision original.

Besides sports and arcade licenses, Mattel gained the rights to many other types of properties, including TSR’s Advanced Dungeons & Dragons pen-and-paper role-playing games, Disney’s Tron (1982) science fiction film, The Electric Company kids’ television series, and Hanna-Barbera cartoons, including Scooby-Doo and The Jetsons. Although the strategy was to gain market share by leveraging familiar brands, Mattel’s talented developers weren’t content to follow the familiar precedent of making lousy games that relied on brand recognition alone to appeal to gamers. This is particularly true of the ambitious TSR-licensed role-playing games, which many fans consider among the best on the platform.

While Mattel eventually shifted its development focus to mainly action games, for a time, the Intellivision did get some excellent games that required cunning, rather than quick reflexes. These titles included ABPA Backgammon (1979), Horse Racing (1980), Reversi (1982), and USCF Chess (1983), the first and last of which were licensed from their respective associations. The chess game is particularly remarkable since it was assumed that the AI for a chess game was well beyond the capabilities of the consoles of the day. Mattel felt, however, that such a product would bolster their claim that the Intellivision was indeed “intelligent television,” and gave the project extra funding. The result was a cartridge with a full 2K of RAM, a luxury no other Mattel cartridges enjoyed. Although the complexity of the programming delayed its release, when it was finally rolled out in 1983, reviewers praised it.

Most of the games set for release in 1983 were advertised as having “SuperGraphics.” The label was intended to help shield the Intellivision against marketing attacks from the newer and more advanced ColecoVision and Atari 5200 SuperSystem. However, in reality, “SuperGraphics” was just a marketing ploy, much like Sega’s later use of “blast processing” to describe games on the Genesis. Though these later Intellivision games did tend to feature better graphics and smoother gameplay than many of the system’s previous titles, there was nothing more to it than increasingly experienced developers using more sophisticated programming routines.

Despite there being only five games released for the Intellivoice, they were some of the system’s most innovative titles. These included Space Spartans (1982), in which aliens relentlessly attack the player’s spaceship and starbases; Bomb Squad (1982), in which the player must follow voice prompts to disarm a terrorist bomb; B-17 Bomber (1982), which simulates a World War II bombing run; and Tron Solar Sailer (1983), in which the goal is to decode an evil computer program.

There was also the ECS-based World Series Major League Baseball (1983), which was one of the first multiangle baseball games, with its fast-paced gameplay based on real statistics, play-by-play with the Intellivoice, and the ability to load and save games and lineups from cassette. Unfortunately, the rarity of the hardware combination allowed only a few gamers to experience programmer Eddie Dombrower’s simulation of the Major League Baseball experience—at least until the release of his popular Earl Weaver Baseball for PC DOS and Commodore Amiga computers four years later.

In 1983, the remaining ECS cartridge lineup was released. These titles included Mind Strike, a challenging, feature-rich board game for one or two players; Mr. BASIC Meets Bits ’N Bytes, which taught computer programming basics through three games and an illustrated 72-page manual; and Melody Blaster, a musical version of Astrosmash and the only other title besides the built-in music program that made use of the music keyboard add-on. Unfortunately, while additional titles were in development before Mattel stopped supporting the ECS, no software took advantage of the additional controller ports for four-player gaming.9

Thin Ice running on the Bliss emulator.

Thin Ice (1986, INTV Corporation)

While Mattel Electronics didn’t have many arcade exclusives in comparison to competitors like Atari or Coleco, they did have a first look deal for many Data East arcade properties, which is why they got top notch titles like Lock ‘n’ Chase and BurgerTime. Occasionally, however, some questionable titles would be offered by Data East to Mattel, like Disco No. 1 (1982), where the player controlled Disco Boy, who skated around a dance floor to trap Disco Girls in squares. The game was fun, but the theme dated. Julie Hoshizaki, who had done a stellar job on the earlier Lock ‘n’ Chase conversion, took Keith Robinson’s proposal for a revision to the arcade game called Thin Ice, and ran with it, with help from Monique Lujan-Bakerink’s graphic designs and George “The Fat Man” Sanger’s8 musical theme, “Carnival of the Penguins.” In the new interpretation, Duncan dunks his fellow penguins when he encloses them on the thin ice, which he loves skating on. After a brief flirtation with changing the character to the official Olympic mascot, Voochko the Wolf, and the further distraction of Mattel Electronics closing down in January 1984, it would take INTV Corporation until 1986 to release the game as originally envisioned.

Even with Mattel’s attempts to lock out third-party developers through the release of the Intellivision II, external software support soon picked up anyway. Besides Coleco, top publishers like Activision, Atarisoft, Imagic, Interphase, Parker Brothers, and Sega all released cartridges for the system after 1982. Although many of these were ports from other systems (mostly the Atari VCS), console exclusives found their way to Mattel’s platform as well. These exclusives included Activision’s Happy Trails (1983), which required a player to create new trail pathways by sliding jumbled pieces into place, and Imagic’s Dracula (1983), which cast the player in the title role as both vampire and bat. In fact, Imagic was particularly prolific on the platform, releasing an additional seven exclusives, bringing its final total to 14 titles.

After Mattel Electronics closed in January 1984, the newly formed Intellivision, Inc., bought all remaining inventory for major toy store and mail order liquidation, including the remaining supply of cartridges from the Intellivision’s third-party software providers. With sales going well for the streamlined company, Valeski decided to try marketing new games. These games included World Series Baseball (now supporting one or two players), Thunder Castle (action role-playing), World Cup Soccer (one or two players), and Championship Tennis (one or two players).

The first two games were completed at Mattel Electronics but never released, and the last two were completed by a former Mattel Electronics office in France and originally saw release in Europe through Dextell Ltd. The success of these new games spurred Valeski to buy out Intellivision Inc.’s assets and form INTV Corp., to more aggressively pursue new Intellivision releases and reprints.

To save money, the company’s new releases and reprints were produced with thinner boxes, contained no controller overlays (or, when absolutely necessary, reduced-quality overlays), featured cartridge labels and instructions that were printed in black and white, and often failed to renew licenses, necessitating a name change for the affected titles.

Despite intense competition in the reinvigorated videogame market, INTV held its own until 1990, releasing 21 additional games in total, six of which were coded from scratch rather than built off pre-existing code. These six originals included sports games Chip Shot Super Pro Golf (1987), Super Pro Decathlon (1988), Body Slam! Super Pro Wrestling (1988), and Spiker! Super Pro Volleyball (1989), as well as arcade translations Commando (1987) and Pole Position (1988). This spirited post-Crash effort helped get approximately 500,000 additional Intellivision consoles into homes, adding to the approximately 3 million units already sold during the platform’s original commercial run.

A screenshot from the Bliss emulator for Imagic’s Swords & Serpents (1982), an impressive action dungeon-crawler featuring one- or two-player simultaneous gameplay as a warrior and wizard.

Tower of Doom running on the Bliss emulator.

Tower of Doom (1987, INTV Corporation)

After the release of the sophisticated role-playing game, Treasure of Tarmin, Mattel Electronics’ marketing arm wanted a less complex, more action-oriented Dungeons & Dragons title as its follow-up. Dan Bass took the lead on ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Revenge of the Master Cartridge, with graphics by Monique Lujan-Bakerink and Karl Morris, and music and sound effects by Dave Warhol and Joshua Jeffe. After being renamed ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Tower of Mystery Cartridge, the game ended up only half complete when Mattel Electronics closed its doors. INTV Corporation commissioned John Tomlinson to finish the rest of the game, along with Connie Goldman, who provided additional graphics. Avoiding the expensive TSR license, the game was released in 1987 as simply Tower of Doom. Even released as late as it was, the game was a triumph for the platform, with a selection of ten different characters of varying abilities, and ten different adventures with either more of a puzzle or action orientation to choose from. Furthering the innovation were a mix of predetermined and random mazes, along with close-up battle scenes whenever a monster was encountered.

The Intellivision Community Then and Now

Despite its quality, the Intellivision was always just a step behind the type of community, third-party, and advertising support that first the Atari VCS and then Coleco’s ColecoVision received. In spite of its underdog status in comparison to those two systems, the Intellivision platform still received more mindshare and support in those critical areas than any of the other contenders for top dog in videogame consoles by a wide margin. The fact that the Intellivision was the only other console of its generation besides the VCS to continue to receive significant support well after the Great Videogame Crash, including prime shelf space at retailers like Toys R Us, speaks volumes to the enthusiasm exhibited by both the platform’s creators and its fans.

Besides Intellivision Productions, Inc.’s own website (www.intellivisionlives.com), there are a wide range of other sites that today’s fans rally around. These include the INTV Funhouse (www.intvfunhouse.com), IntelliWiki (wiki.intellivision.us), Intellivision (www.intellivision.us), and Intellivision Revolution (http://intellivisionrevolution.com). Of course, general sites like AtariAge (www.atariage.com) and Digital Press (www.digitpress.com) have regular discussions about the platform, or even dedicated forums. Of course, many of the users on these forums were active Intellivision fans back in the day, with stories like Graydingo’s:

My dad picked up an Intellivision circa 1980. I became so good at Snafu that no one wanted to play me. Still to this day I love the ‘SNAP, PEWWWW’ sound FX of that game. I played a lot of Astrosmash as well. It started a lifelong love of games and consoles.

In short, today there’s no lack of information or community surrounding the Intellivision. If you’re interested in collecting, emulating, or just learning more about the system, joining one of these forums and introducing yourself is a great way to get started.

One major factor for the resilience of the community today is due to Intellivision Productions’ continued licensing and release of their own products, including the Intellivision Lives! game collection, which was first released for Window-based computers in 1999, and was followed by versions for Sony’s PlayStation 2, Microsoft’s Xbox, and Nintendo’s GameCube and DS platforms, as well as the similar Intellivision for iOS devices. Another major factor is the growing collection of quality homebrew software releases that has really been kicked into high gear in recent years.

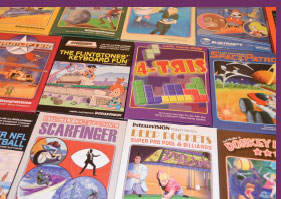

With a combination of previously unreleased prototypes, like the 2011 IntelligentVision releases of the James Bond-themed action game Scarfinger and the ECS-based Flintstones’ Keyboard Fun, and original creations like the incredible Moon Patrol-inspired ECS-enhanced Space Patrol (2007, Left Turn Only Productions), the combined ports of Donkey Kong and D2K: Jumpman Returns! as D2K Arcade (2012, Elektronite), and the polished maze game, Christmas Carol vs. The Ghost of Christmas Presents (2012, Left Turn Only Productions), there are no shortage of quality new cartridge releases for the active fan to plug into their console.

A collection of modern-day homebrew releases. Many of these titles match or exceed the packaging quality found in the boxed games from the Intellivision’s heyday.

Collecting for and Emulating the Intellivision

With a decade of releases in its mass market prime, Intellivision systems and variations are easy to find and relatively inexpensive, often selling in cost-effective bundles with many loose games and an Intellivoice, although care must be taken that the controllers are in good working condition since they’re difficult to replace. The ECS add-on is rarer and often goes for quite a bit more than the console with some games. The music keyboard add-on often goes for a little more than the ECS alone.

Since the Intellivision Keyboard Component had such a limited production run and many were recalled, that particular add-on is among the rarest items for any system. When a Keyboard Component becomes available, even if it’s not fully functional, it will sell for well into the thousands of dollars. As expected, the software is even rarer and comprises the BASIC Programming Language cartridge and the Conversational French, Crosswords (I-III), Family Budgeting, Geography Challenge, Jack LaLanne’s Physical Conditioning, and Spelling Challenge cassettes.

Utopia running on the Bliss emulator.

Utopia (1981, Mattel)

Having already won countless industry awards and accolades, it’s little wonder that Utopia was chosen as just one of 80 videogames to appear in the Smithsonian Institution’s The Art of Video Games exhibition that took place March 16–September 30, 2012. Don Daglow’s breakthrough simulation helped set the template for the popular real-time strategy (RTS) genre, requiring the planning and thinking ahead of a game of chess with the reflexes of an action videogame to set the strategies in motion. Tasked with ruling one of two opposing islands, players could play competitively or cooperatively to increase the welfare of their respective peoples and their need for food, housing, and other essentials in the face of natural disasters, and even rebels. For the only official port of the game, check out the Mattel Aquarius version, which retains the original’s charms, while taking into account its target platform’s relative strengths and weaknesses.

New hardware has thus far been mostly limited to low production run cartridges that allow loading of ROM images and assist with programming, such as Chad Schell’s Intellicart and Cuttle Cart 3. Other devices, like the Ultima PC Interface for the Intellivision from Hafner Enterprises, allow connection of real Intellivision controllers, as well as the ECS keyboard and music synthesizer, making emulating the console on a computer all the more authentic.

Besides the official Intellivision emulation compilations released by Intellivision Productions for modern platforms, a variety of other unofficial emulators are available that can deliver a good approximation of the real system experience. These emulators include Kyle Davis’ Bliss for Windows and Joes Zbiciak’s jzIntv for Windows, Macintosh, and Linux, with many of the better ones also doing a good job of emulating the functionality of the ECS and other add-ons.

For a nice compromise between the authenticity of the actual console and emulation, inquisitive fans would do well to check out AtGames’ officially licensed digital apps and Intellivision Flashback TV Game system, which were released in 2014. While the console can only play the selection of Intellivision games it has built-in, it’s an inexpensive, low hassle way to experience the platform on a dedicated device.

The Bliss Windows emulator running Joseph Zbiciak’s Tetris clone 4-Tris (2000), one of the first cartridge homebrew releases for the platform.

1 Fun fact: Plimpton’s 1966 non-fiction book Paper Lion, where he recounted his experiences trying out as the third-string quarterback for the 1963 Detroit Lions, was dramatized in a 1968 film of the same name. The star of that film? Alan Alda, of course.

2 The See ’n Say toys allowed children to choose the item they wanted to hear. The Farmer edition allowed even the most urban of children to hear what a duck or cow sounded like. Instead of batteries, the units were powered by a metal coil, wound manually by pulling on a string.

3 TSR was particular about use of their license and making a clear distinction with their other products, which is why there’s the capitalization and “Cartridge” in the games they allowed Mattel to produce.

4 TSR themselves produced and published two mediocre computer games for the Apple II in 1982, Dungeon! and Theseus and the Minotaur. Outside of Mattel’s 1983 port of ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Treasure Of Tarmin Cartridge for the Aquarius, those would be the last official TSR games on a computer until SSI’s triumphant 1988 release of the first “Gold Box” role-playing classic, Pool of Radiance.

5 Sadly, Mattel’s other Battlestar Galactica licensed products did not prove as successful for the company. After a four-year-old tragically choked to death after swallowing a missile part from one of the toys, Mattel spent half a million dollars recalling the line.

6 Easter Egg: If you own an Intellivision and a copy of this game on cartridge, you can rapidly press the console’s reset button to unlock the original Asteroids-inspired variation of the game that was unintentionally left in. Unfortunately, there’s no way to reliably access this variation other than trying to glitch the console with the reset button.

7 During INTV’s operation, Mattel did not remain idle. The toy company became involved in the videogame industry again by affiliating with Nintendo in 1986. Mattel not only produced new software and peripherals for the Nintendo Entertainment System, but also handled distribution throughout Europe in 1987 and Canada from 1986 to 1990 on Nintendo’s behalf.

8 This was George Alistair Sanger’s first videogame soundtrack, which lasted all of 15 seconds. Under his nickname, The Fat Man, he has gone on to produce a long list of increasingly complex videogame soundtracks. See author Barton’s series of interviews with Sanger here: http://www.armchairarcade.com/neo/taxonomy/term/2979.

9 The last game finished at Mattel Electronics - the day before the final layoff - was Dave Stifel’s innovative Game Factory (aka, Game Maker) for the ECS, which let you create your own games from a library of components, including being able to borrow characters from other cartridges! It was yet another example of a potential pre-Crash game changer that was sadly never released.